Funding Public Law: What it costs and how to pay for it

advertisement

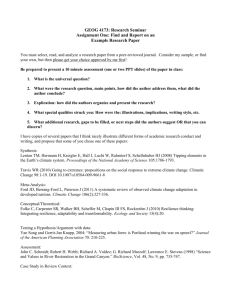

Funding Public Law: What it costs and how to pay for it By Ravi Low-Beer, Solicitor, The Public Law Project 1. This session will focus on challenges by the citizen to decisions of a public body, including housing law, immigration law, planning law, community care law, education law, welfare benefits law, mental health law and prison law. 2. The first question (“What does public law cost?) can be quickly answered: when we factor in legal costs paid directly by individual complainants, publicly funded costs, and the costs paid by public bodies defending claims, the answer is that we do not know how much public law costs. Except that it probably costs a lot. 3. So we will consider instead how to get funding to bring public law cases, ie: 4. The aims of the session are: 5. to give an overview of the legal aid and costs systems; and to introduce different funding options for different types of cases. As a general rule, cases against public bodies are funded: 6. Disputes between citizens and public bodies (usually conducted in telephone conversations, letters and emails, and sometimes, face to face meetings); ADR, eg mediation; Formal complaints about public bodies to the public bodies themselves and to Ombudsmen such as the Local Government Ombudsman, and the Parliamentary and Health Service Ombudsman; Appeals to administrative tribunals; Proceedings before the civil courts, eg claims for judicial review and statutory appeals to the court. by the state through the legal aid system; by clients directly; by insurance companies; through Conditional Fee Agreements. These are considered in turn below together with Protective Costs Orders, by which the court can restrict the potential costs liability of a judicial review litigant at the outset of the case. Legal aid 7. By way of introduction, here are some statistics: “Our legal aid system is one of the best funded in the world. We spend around £38 per head on it annually in England and Wales, compared to £4 1 in Germany and £3 in France. Even countries with a legal system more like ours spend less; for example, both New Zealand and the Republic of Ireland spend around £8 per head”1 and “In 2008-09, legal aid resource expenditure was £2.09 billion, with £0.91 billion spent on 1.3 million civil acts of assistance, and £1.18 billion on 1.6 million criminal acts of assistance. £124.4 million was spent on administration. … Total cash spending on civil legal aid rose from £792m in 2000/01 to £846m in 2004/05. In 2008/09 this figure had reached £914.1m. This represents a 2% year on year increase since 2001. Family legal aid cash expenditure has grown by an average of 5% per annum from 1999/00 and 2008/09, accounting for £624m of total in 2008/09 –the highest level of expenditure in family legal aid to date.”2 8. Legal aid was established in England and Wales more than 60 years ago, by the Legal Aid and Advice Act 1949. Its present incarnation is more than 10 years old: section 1 of the Access to Justice Act 1999 established the Legal Services Commission, to administer two services, the Community Legal Service and the Criminal Defence Service. Together, these two services constitute the legal aid system in England and Wales, for civil and criminal matters. They are run under the auspices of the Ministry of Justice. 9. However, following concerns about the operation of the legal aid system by the National Audit Office, and a report by Sir Ian Magee, the Government announced on 3 March 2010 that the Legal Services Commission is to be abolished and replaced with an Executive Agency.3 So much of what follows is set to change. What services can be funded as part of the Community Legal Service? 10. Section 4 of the Access to Justice Act 1999 (“the Act”) establishes the Community Legal Service and specifies what services it can provide. It states: “(1) The Commission shall establish, maintain and develop a service known as the Community Legal Service for the purpose of promoting the availability to individuals of services of the descriptions specified in subsection (2) and, in particular, for securing (within the resources made 1 Legal Aid: Refocusing on Priority Cases http://www.justice.gov.uk/consultations/docs/legal-aidrefocusing-on-priority-cases-consultation.pdf which is a direct link to the document rather than the website 2 Review of legal aid delivery and governance by Sir Ian Magee, paragraphs 8, 72 and 73, http://www.justice.gov.uk/publications/docs/legal-aid-delivery.pdf 3 http://www.justice.gov.uk/news/newsrelease030310d.htm 2 available, and priorities set, in accordance with this Part) that individuals have access to services that effectively meet their needs. (2) 11. The descriptions of services referred to in subsection (1) are— (a) the provision of general information about the law and legal system and the availability of legal services, (b) the provision of help by the giving of advice as to how the law applies in particular circumstances, (c) the provision of help in preventing, or settling or otherwise resolving, disputes about legal rights and duties, (d) the provision of help in enforcing decisions by which such disputes are resolved, and (e) the provision of help in relation to legal proceedings not relating to disputes.” Section 6(6) provides that the services listed in Schedule 2 cannot be funded under the Community Legal Service. Schedule 2 states: “The services which may not be funded as part of the Community Legal Service are as follows. 1. Services consisting of the provision of help (beyond the provision of general information about the law and the legal system and the availability of legal services) in relation to— (a) allegations of personal injury or death, other than allegations relating to clinical negligence, (aa) allegations of negligently caused damage to property, (b) conveyancing, (c) boundary disputes, (d) the making of wills, (e) matters of trust law, (ea) the creation of lasting powers of attorney under the Mental Capacity Act 2005, (eb) the making of advance decisions under that Act, (f) defamation or malicious falsehood, (g) matters of company or partnership law, or (i) attending an interview conducted on behalf of the Secretary of State with a view to his reaching a decision on a claim for asylum (as defined by section 167(1) of the Immigration and Asylum Act 1999. 1A. Services consisting of the provision of help to an individual in relation to matters arising out of or in connection with— (a) a proposal by that individual to establish a business; (b) the carrying on of a business by that individual (whether or not the business is being carried on at the time the services are provided); (c) the termination or transfer of a business that was being carried on by that individual. 2. Advocacy in any proceedings except— 3 (1) proceedings in— (a) the Supreme Court, (c) the Court of Appeal, (d) the High Court, (e) any county court, (f) the Employment Appeal Tribunal, (g) the First-tier Tribunal under any provision of the Mental Health Act 1983 or paragraph 5(2) of the Schedule to the Repatriation of Prisoners Act 1984, or the Mental Health Review Tribunal for Wales, (gza) the First-tier Tribunal under— (i) Schedule 2 to the Immigration Act 1971, (ii) section 40A of the British Nationality Act 1981, (iii) Part 5 of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002, or (iv) regulation 26 of the Immigration (European Economic Area) Regulations 2006, (ga) the Upper Tribunal arising out of proceedings within paragraph (g) or (gza), (i) the Proscribed Organisations Appeal Commission. (2) proceedings in the Crown Court— (a) for the variation or discharge of an order under section 5 of the Protection from Harassment Act 1997, (b) which relate to an order under section 10 of the Crime and Disorder Act 1998, (d) which relate to an order under paragraph 6 of Schedule 1 to the Anti-terrorism, Crime and Security Act 2001, or (e) under the Proceeds of Crime Act 2002 to the extent specified in paragraph 3, (3) proceedings in a magistrates' court— (a) under section 43 or 47 of the National Assistance Act 1948, section 22 of the Maintenance Orders Act 1950, section 4 of the Maintenance Orders Act 1958 or section 106 of the Social Security Administration Act 1992, (b) under Part I of the Maintenance Orders (Reciprocal Enforcement) Act 1972 relating to a maintenance order made by a court of a country outside the United Kingdom, (c) in relation to an application for leave of the court to remove a child from a person's custody under [section 36 of the Adoption and Children Act 2002] or in which the making of [a placement order or adoption order (within the meaning of the Adoption and Children Act 2002) or an order under section 41 or 84 of that Act is opposed by any party to the proceedings, (d) for or in relation to an order under Part I of the Domestic Proceedings and Magistrates' Courts Act 1978 or Schedule 6 to the Civil Partnership Act 2004, (da) under section 55A of the Family Law Act 1986 (declarations of parentage), 4 (e) (f) (g) (h) (i) (j) (k) (l) (4) under the Children Act 1989, under section 30 of the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Act 1990, under section 20 of the Child Support Act 1991, under Part IV of the Family Law Act 1996, for the variation or discharge of an order under section 5 of the Protection from Harassment Act 1997 , under section 8 or 11 of the Crime and Disorder Act 1998, for an order or direction under paragraph 3, 5, 6, 9 or 10 of Schedule 1 to the Anti-terrorism, Crime and Security Act 2001, for an order or direction under section 295, 297, 298, 301 or 302 of the Proceeds of Crime Act 2002, and proceedings before any person to whom a case is referred (in whole or in part) in any proceedings within paragraphs (1) to (3).” 12. It is not necessary to go in detail in the excluded services. In relation to social welfare public law cases, the main funding gap appears to be the exclusion of funding for advocacy at inquests and on appeals before most tribunals (save for the Employment Appeal Tribunal, the Proscribed Organisations Appeal Commission, and the First-Tier and Upper Tribunal hearing mental health and immigration appeals (under paragraph 2(1)(g),(gza) and (ga) of Schedule 2)). 13. The reason why representation before most tribunals is excluded is that the view has traditionally been taken that most tribunals are well suited to the needs of unrepresented clients, so that representation is not, in general, necessary. The exceptions for mental health and immigration appeals reflect an acceptance of the importance of representation in those categories of cases. Lord Chancellor’s power to direct that excluded services can be funded by the LSC 14. But the exclusions in section 6(6) and Schedule 2 to the Act are subject to section 6(8), which states: “The Lord Chancellor — (a) may by direction require the Commission to fund the provision of any of the services specified in Schedule 2 in circumstances specified in the direction, and (b) may authorise the Commission to fund the provision of any of those services in specified circumstances or, if the Commission request him to do so, in an individual case.” 15. Funding for representation before tribunals excluded under Schedule 2 to the Act can therefore be made available (1) in any class of case; and (2) in any individual case where the Lord Chancellor makes a direction under section 6(8). Such funding is known as “exceptional funding”, and it is considered further at paragraphs 43-49 below. How the LSC decides which services to fund – the Funding Code 5 16. Section 8(1) of the Act states: “The Commission shall prepare a code setting out the criteria according to which it is to decide whether to fund (or continue to fund) services as part of the Community Legal Service for an individual for whom they may be so funded and, if so, what services are to be funded for him”. 17. A Code has been published by the LSC in relation to the operation of the Community Legal Service. It is called the Funding Code. In the event of a legal aid query, it is usually a good starting point. It is divided into three parts: (1) (2) (3) 18. The Code sets out 6 levels of service. These are: (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) 19. Part A: Criteria4; Part B: Procedures5; and Part C: Decision-making Guidance. This is separated into: General principles (sections 1-14) 6 Other guidance (sections 15-19, 21-26 and 28)7 Children and family (section 20)8 An updated section 22 concerning representation before tribunals in light of the Tribunals, Courts and Enforcement Act 20079 Exceptional Funding (section 27)10 Immigration (section 29).11 Legal Help Help at Court Family Help (which can either be Lower of Higher) Legal Representation Family Mediation Services authorised by the Lord Chancellor The different levels of service are essentially different types of legal aid, the most important of which, for present purposes, are Legal Help in relation to advice and assistance in public law matters, and Legal Representation in relation to proceedings before courts and the immigration and mental health tribunals. These are considered in more detail below. The Code sets merits criteria which vary according to the level of service, nature of case and stage of proceedings. 4 http://www.legalservices.gov.uk/docs/civil_contracting/Funding_code_criteria_Jul07.pdf http://www.legalservices.gov.uk/docs/cls_main/Procedure.pdf 6 http://www.legalservices.gov.uk/docs/cls_main/FundingCodeDecisionMakingGuidanceGeneralPrinci ples(Sections1-14)Sept07.pdf; 7 http://www.legalservices.gov.uk/docs/cls_main/FundingCodeDecisionMakingGuidanceOtherGuidance(Sections15-19_21-26and28)Sept07.pdf 8 http://www.legalservices.gov.uk/docs/cls_main/FundingCodeDecisionMakingGuidanceFamily(Sectio ns20)Sept07.pdf 9 http://www.legalservices.gov.uk/docs/civil_contracting/Tribunals.pdf 10 http://www.legalservices.gov.uk/docs/cls_main/FundingCodeDecisionMakingGuidanceExceptionalF unding(Section27)Sept07.pdf 11 http://www.legalservices.gov.uk/Final_amended_s29_GH_020609.pdf 5 6 Controlled and licensed work 20. A distinction is drawn in the Code between controlled and licensed work. Controlled work is granted on application by the client to the supplier whereas licensed work is granted on application by the client to the LSC. Legal Help is controlled work. 21. Legal representation is sometimes provided as controlled work (for example, in respect of representation on mental health and immigration appeals, in which case it is referred to as “Controlled Legal Representation”). Otherwise it is conducted as licensed work under certificates issued by the LSC, known as “funding certificates”. 22. The vast majority of public law cases are funded as Legal Help, Help at Court, Legal Representation and (very occasionally) as exceptional funding cases. Each of these is considered further below. Legal Help 23. Legal Help covers12: (1) (2) (3) (4) 24. the provision of help by the giving of advice as to how the law applies in particular circumstances, the provision of help in preventing, or settling or otherwise resolving, disputes about legal rights and duties, the provision of help in enforcing decisions by which such disputes are resolved, and the provision of help in relation to legal proceedings not relating to disputes. Legal Help does not cover services excluded by section services excluded by section 6(6) and Schedule 2 to the Act (see above), nor does it cover: (1) (2) (3) (4) The provision of general information about the law and legal system and the availability of legal services (except where such provision is incidental to the provision of help in a specific case). Issuing or conducting court proceedings. Advocacy or instructing an advocate in proceedings. The provision of mediation or arbitration (but this does not prevent legal help being given in relation to mediation or arbitration or covering payment of a mediator’s or arbitrator’s fees as a disbursement). Criteria for Legal Help 25. 12 The Code sets out two criteria for Legal Help (aside from specific contractual conditions and those relating to financial eligibility). It provides13 that Legal Help may only be given: FC/A/2.1 (= Section 2.1 of Part A of the Funding Code) 7 (1) where there is sufficient benefit to the client, having regard to the circumstances of the matter, including the personal circumstances of the client, to justify work or further work being carried out. (2) if it is reasonable for the matter to be funded out of the Community Legal Service Fund, having regard to any other potential sources of funding. Help at Court 26. Help at Court is a level of service the grant of which authorises help and advocacy for a client in relation to a particular hearing, without formally acting as legal representative in the proceedings, unless this is authorised by the Commission. 27. The criteria for Legal Help apply to an application for Help at Court, in addition to the following two criteria14: (1) Help at Court may only be provided if the nature of the proceedings and the circumstances of the hearing and the client are such that advocacy is appropriate and will be of real benefit to the client; and (2) Help at Court may not be provided if the contested nature of the proceedings or the nature of the hearing is such that, if any help is to be provided, it is more appropriate that it should be given through Legal Representation. Legal representation 28. A grant of Legal Representation authorises legal representation for a party to proceedings or for a person who is contemplating taking proceedings15. This includes: (1) (2) (3) (4) Litigation services. Advocacy services. All such help as is usually given by a person providing representation in proceedings, including steps preliminary or incidental to proceedings. All such help as is usually given by such a person in arriving at or giving effect to a compromise to avoid or bring to an end any proceedings. 29. Note, as stated above, that advocacy before most tribunals (save in mental health, immigration and certain other matters) is an excluded service, and so Legal Representation is in general not available. 30. There are in general two types of Legal Representation, Investigative Help and Full Representation. 13 FC/A/5.2 FC/A/5.3 15 FC/A/2.1 14 8 (1) “Investigative Help” means Legal Representation which is limited to investigation of the strength of a proposed claim. Investigative Help includes the issue and the conduct of proceedings only so far as necessary to obtain disclosure of relevant information or to protect the client’s position in relation to any urgent hearing or time limit for the issue of proceedings. (2) “Full Representation” means a grant of Legal Representation other than Investigative Help. Standard criteria for both Investigative Help and Full Representation 31. There are a number of criteria to be met before Legal Representation is granted (as one might expect, more than must be met before Legal Help is given). Particular criteria are set out in relation to different categories of law in sections 7 to 15 of Part A of the Code. But the Code sets out some standard criteria, that are always applicable where an application is made for Investigative Help and Legal Representation. These are16: (1) Alternative Funding: An application may be refused if alternative funding is available to the client (through insurance or otherwise) or if there are other persons or bodies, including those who might benefit from the proceedings, who can reasonably be expected to bring or fund the case. For the purpose of this criterion only, alternative funding does not include funding by means of a conditional fee agreement. (2) Alternatives to Litigation: An application may be refused if there are complaint systems, ombudsman schemes or forms of alternative dispute resolution which should be tried before litigation is pursued. (3) Other Levels of Service: An application may be refused if it appears premature or if it appears more appropriate for the client to be assisted by some other level of service under the Code, such as Legal Help or Help at Court. (4) The Need for Representation: An application may be refused if it appears unreasonable to fund representation, for example in the light of the nature and complexity of the issues, the existence of other proceedings or the interests of other parties in the proceedings to which the application relates. (5) Small Claims: An application will be refused if the case has been or is likely to be allocated to the small claims track. Additional criteria for Investigative Help 16 FC/A/5.4 9 32. Separate additional criteria are set out in the Code for Investigative Help and for Full Representation. In relation to Investigative Help, the additional criteria are17: (1) Potential for a Conditional Fee Agreement: Investigative Help may be refused if the nature of the case and circumstances of the client are such that investigative work should be carried out privately with a view to a conditional fee agreement (see below). (2) The Need for Investigation: Investigative Help may only be granted where the prospects of success of the claim are uncertain and substantial investigative work is required before those prospects can be determined. Guidance may indicate what constitutes substantial investigative work for this purpose. (3) Damages: If the client’s claim is primarily a claim for damages and has no significant wider public interest, Investigative Help will be refused unless the damages are likely to exceed £5,000. (4) Prospects after Investigation: Investigative Help may only be granted if there are reasonable grounds for believing that when the investigative work has been carried out the claim will be strong enough, in terms of prospects of success and cost benefit, to satisfy the relevant criteria for Full Representation. Additional criteria for Full Representation 33. 17 18 In relation to Full Representation, the additional criteria are18: (1) Conditional Fee Agreements: If the nature of the case is suitable for a CFA, and the client is likely to be able to avail himself or herself of a CFA, Full Representation will be refused. (2) Prospects of Success: Full Representation will be refused if: (i) Prospects of success are unclear; (ii) Prospects of success are borderline and the case does not appear to have a significant wider public interest or to be of overwhelming importance to the client; or (iii) Prospects of success are poor. (3) Cost Benefit – Quantifiable Claims: If the claim is primarily a claim for damages by the client and does not have a significant wider public interest, Full Representation will be refused unless the following cost benefit criteria are satisfied: (i) If prospects of success are very good (80% or more), likely damages must exceed likely costs; Section 5.6 Section 5.7 of Part A of the Funding Code 10 (ii) If prospects of success are good (60%–80%), likely damages must exceed likely costs by a ratio of 2:1; (iii) If prospects of success are moderate (50%–60%), likely damages must exceed likely costs by a ratio of 4:1. (4) Cost Benefit – Unquantifiable Claims: If the claim is not primarily a claim for damages (including any application by a defendant or a case which has overwhelming importance to the client), but does not have a significant wider public interest, Full Representation will be refused unless the likely benefits to be gained from the proceedings justify the likely costs, such that a reasonable private paying client would be prepared to litigate, having regard to the prospects of success and all other circumstances. (5) Cost Benefit – Public Interest Cases: If the claim has a significant wider public interest, Full Representation may be refused unless the likely benefits of the proceedings to the applicant and others justify the likely costs, having regard to the prospects of success and all other circumstances. Other topic-specific criteria for Investigative Help and Full Representation 34. Additional criteria for Investigative Help and Full Representation are set out in Part A of the Funding Code, in section 7 for judicial review cases; in section 8 for claims against public authorities; in section 9 for Clinical Negligence; in section 10 for housing; in section 11 for Family; in section 12 for mental health; and in section 13 for immigration. 35. The above criteria can be represented pictorially as follows: Criteria for Investigative Help Criteria for Full Representation Alternative Funding Alternatives to Litigation Other Levels of Service The Need for Representation Small Claims (section 5.4 of FC, Part A) + Potential for a CFA The Need for Investigation Damages Prospects After Investigation + CFA Prospects of Success Cost Benefit – Quantifiable Claims Cost Benefit – Unquantifiable Claims Cost Benefit – Public Interest Cases (section 5.6 of FC, Part A) (section 5.7 of FC, Part A) + Category Specific Criteria (for IH) + Category Specific Criteria (for FR) (sections 7-15 of FC, Part A) (sections 7-15 of FC, Part A) 11 Public interest cases 36. Whether a case has significant wider public interest is relevant in two ways when the criteria for Legal Representation are applied: (1) in the operation of the cost benefit test; and (2) where the merits of the claim are no more than borderline. Public interest and the cost benefit test 37. The Funding Code requires a case to be of sufficient benefit to the client before it will be funded. At Legal Help level, there is no more than a blanket requirement of sufficiency. At Legal Representation level (and particularly before a grant of Full Representation), the issue of cost benefit is tested far more stringently, by reference to (1) prescribed ratios between the estimated prospects of success and the likely damages (in quantifiable cases); and (2) the “privately paying client test” (in unquantifiable cases). 38. There is an exception to these rules in cases which are assessed to have significant wider public interest. In such cases (and only in such cases), the benefit to the wider public can be aggregated with the benefit to the individual litigant in order to satisfy the cost benefit test. Borderline cases 39. Where the prospects of success are assessed as “borderline”, the standard criteria for Full Representation require funding to be refused unless the case attracts a significant wider public interest (although note that in judicial review cases, full representation will also granted if the case raises significant human rights issues)19. How is Wider Public Interest assessed? 40. Guidance on public interest cases is set out in section 5 of Part C of the Funding Code. “Wider Public Interest” is defined at section 5.2 as follows: ‘“Wider public interest” means the potential of the proceedings to produce real benefits for individuals other than the client (other than benefits to the public at large which normally flow from proceedings of the type in question). This definition is set out at section 2.4 of the Code.’ 41. “Significant Wider Public Interest” is defined at section 5.3, as follows: “1. 19 Wider public interest as defined only has an impact in the Code if it is “significant”. A common sense approach must be adopted to decide whether a case has a significant wider public interest. Much FC/A/7.4.5(ii) 12 will depend on the nature of the benefits alleged and how directly other persons may benefit from the case in question. The more intangible and indirect the benefits are, the harder it will be to show that there is a significant wider public interest. Speculative and farfetched public interest, or the mere possibility that a case outcome could conceivably benefit other members of the public would not qualify. 42. 2. The Code sets no limit or minimum on the number of people who must benefit before significant wider public interest can be established. This will vary greatly according to the nature of the benefits. If the benefits alleged are general quality of life considerations, such as noise nuisance for example, the number of persons affected must be very substantial before a significant wider public interest can be established. Public interest carries with it a sense that large numbers of people must be affected. As a general guideline, even where the benefits to others are substantial, it would be unusual to regard a case as having a significant wider public interest if fewer than 100 people would benefit from its outcome. 3. It may be particularly difficult to quantify the public interest in a case which seeks to establish a new legal precedent or issue of law. In such cases the people who will benefit will be future clients who are unlikely to be easily identifiable at the time the public interest case is pursued. In such cases it may be necessary to estimate how many such cases will come forward each year and to estimate for how long the legal precedent is likely to continue to have an effect. 4. In deciding whether a case which raises a new point of law has a significant wider public interest, it is necessary to consider how likely it is that the court will change or clarify the law in deciding the case. The mere fact that an area of law is unclear so that it is possible that the court may clarify the law is not enough to establish a significant wider public interest. It is more likely that there will be a significant wider public interest if a case directly raises a specific point of law which the court will have to resolve one way or another. 5. Note that in deciding whether a case has a significant wider public interest it is only necessary to show that the case can produce real benefits for individuals other than the client, for example in the ways described in section 5.2 above. It is not appropriate at this stage to consider competing public interests or any disbenefit which the case may bring to other persons.” The LSC has established a panel known as the Public Interest Advisory Panel (PIAP) to make recommendations about the level of public interest (whether it be exceptional wider public interest, high wider public interest, significant wider public interest, or no significant wider public interest). The Panel’s 13 reports are sent to the applicant for comment, and are then taken into account by the LSC. They do not bind the LSC. Exceptional funding 43. Recall (see paragraphs 11-15 above) that: (1) (2) (3) (4) 44. certain services are excluded from being funded by the LSC by section 6(6) of the Act and Schedule 2; by section 6(8) of the Act, services can be “un-excluded” (brought within scope) where the Lord Chancellor makes a direction; such directions can apply to a class of cases, or to an individual case; the resulting funding is known as “exceptional funding”. On 1 November 2001, the Lord Chancellor issued a direction bringing back into scope the funding of representation of an immediate family member of a deceased person, where the death occurred: “(1) in police or prison custody, (2) during the course of police arrest, search, pursuit or shooting; or (3) during the compulsory detention of the deceased under the Mental Health Act 1983. Such services may be funded where the Commission is satisfied that funded representation is necessary to assist the coroner to investigate the case effectively and establish the facts”. 45. The Lord Chancellor’s guidance on exceptional funding is set out in FC/C/27. It is stated to apply both to the class of inquests brought into scope by the Lord Chancellor’s direction of 1 November 2001, and also to applications for funding individual excluded cases under section 6(8)(b) of the Act (which can include funding for representation at inquests not covered by the Lord Chancellor’s direction). 46. The procedure is different in inquest cases subject to the Lord Chancellor’s direction and in other cases (including other inquest cases). In inquest cases subject to the Lord Chancellor’s direction, the cases are within scope, and therefore the LSC has the power to grant funding. In other individual cases, only the Lord Chancellor has the power to authorise funding, albeit on the LSC’s recommendation. So all applications for exceptional funding should be made at first instance to the LSC’s Special Cases Unit. The criteria are different for inquests, and for other proceedings. Inquests 47. For inquests, the basic criteria are stated to be either: (1) There is a significant wider public interest, as defined by the funding code guidance, in the applicant being legally represented at the inquest; or 14 (2) 48. Funded representation for the family of the deceased is likely to be necessary to enable the coroner to carry out an effective investigation into the death, as required by Article 2 of ECHR. For this purpose ‘family’ should be given a wide interpretation, in line with the funding code guidance. The LSC has the discretion to waive financial eligibility restrictions in certain such cases. Other excluded proceedings 49. In other excluded proceedings, at least one of the following criteria must apply: (1) There is a significant wider public interest (as defined in the Funding Code) in the resolution of the case and funded representation will contribute to it. (2) The case is of Overwhelming Importance to the Client as defined in the Code. (3) There is convincing evidence that there are other exceptional circumstances such that without public funding for representation it would be practically impossible for the client to bring or defend the proceedings, or the lack of public funding would lead to obvious unfairness in the proceedings20. Legal aid materials - where to look 50. Reference to the following documents will (hopefully) solve most civil legal aid queries: 51. The Access to Justice Act 1999; The 3 volumes of the Funding Code; The Unified Civil Contract and applicable category specific specifications; Individual case contracts; Any other applicable contracts. The Access to Justice Act 1999 and the Funding Code have been considered above. The relevant contractual material will be: (1) the Unified Civil Contract21 (a contract between the LSC and all contracted service providers); This criterion is sometimes referred to as “Jarrett complexity” Note that this will expire on 13 October 2010, and a staged tender process is currently underway. The tendering timetable is set out in the most recent (February 2010) edition of the LSC’s newsletter Focus (http://www.legalservices.gov.uk/docs/news/focus_64.pdf) at page 11. The deadline for applicants for contracts is stated to be: (1) under the mental health category, noon on 31 March 2010, (2) under the social welfare law and family law categories, 21 April 2010, and (3) for all other civil categories, the week commencing 26 April 2010. 20 21 15 (2) individual case contracts. The most common example of this is when a case is treated as a high cost case usually if projected costs and disbursements exceed £25,000. In such cases, the amount of funding is agreed and specified in an individual case contract. (3) ad hoc contracts with suppliers, eg for the provision of telephone advice. Cases funded other than by legal aid Special factors where litigation is being funded 52. Before considering how to bring public law cases where the client is not eligible for legal aid, we should consider some special factors arising where litigation (as opposed to advice and general legal assistance) is being funded. These factors are particularly present in judicial review cases, judicial review being the main procedure for litigating public law disputes. They are that: (1) Litigation cases tend to be more expensive than other types of public law case (eg complaints); (2) Although the court has a wide discretion in making orders as to costs22, the usual order is that the loser pays the winner’s legal costs. That means that parties to litigation need to be sure (a) that they have the means of paying for their legal representation; and (b) that they can pay the costs of their opponent if they lose and the court decides to make the usual costs order against them. 53. Both of these problems are alleviated where legal aid is granted to enable litigation to be brought. Once legal aid is granted, the assisted person’s legal costs will be paid by the LSC (or by the opponent, if the case results in an order that the assisted person’s costs are paid by the opponent). So the first problem of expense does not arise so far as the client is concerned, save indirectly in the operation of the costs benefit test. 54. The second problem of potential liability to pay the opponent’s legal costs is addressed in section 11(1) of the Act, and regulations made under that section, which confer on a legally aided person what is known as “costs protection”. In practice, this means that when a legally assisted party to litigation loses, then, providing the funding certificate is not revoked, the winning party cannot recover its costs against the assisted person without a further order of the court for the period that the funding certificate was in force. Permission of the court will in practice only be granted if the winning party can provide evidence that the assisted person’s means have increased since the grant of legal aid (for example, as a result of a lottery win). In 16 years of practice, I have not known this to happen. 22 Civil Procedure Rules, Part 44.3 http://www.justice.gov.uk/civil/procrules_fin/contents/parts/part44.htm#IDADESZ 16 Privately paying clients 55. There is little to say about privately paying clients. In most arrears of social welfare law, the vast majority of individuals involved in a public law dispute with a public body do not have the resources to pay for the legal advice or representation that they need. This is particularly so where the client wishes to litigate, for the reasons set out above. 56. Sometimes insurance companies can pay legal costs. There are two main types of insurance, Before The Event Insurance and After The Event Insurance. Before The Event insurance 57. Before The Event insurance refers to an insurance policy that the client takes out in advance of a case, by which in return for paying a premium, the client’s legal costs are paid by the insurance company, to cover pre-agreed types of claim. Before The Event insurance tends to cover private law matters, such as personal injury, and disputes relating to buildings. It is not well suited to public law disputes, and in practice not available to assist in most public law cases. Conditional Fee Agreements 58. A Conditional Fee Agreement (CFA) is an agreement pursuant to which a lawyer agrees with the client to be paid a success fee in the event of the claim succeeding, where the success fee is not calculated as a proportion of the amount recovered by the client. A typical example of a CFA is where a lawyer is retained on a “no win, no fee” basis. It is only available in practice in litigation, where the court has the power to award costs against the losing party (so that the client’s legal costs end up being paid by the losing party). 59. A CFA is part of the solution for litigant who is not financially eligible for legal aid. But the client whose legal team is “paid for” by a CFA does not have the costs protection enjoyed by the legally aided client. So a litigant with a CFA must limit potential liability for the other side’s costs in another way. Two ways are considered below, After The Event insurance, and Protective Costs Orders. After The Event Insurance 60. After The Event insurance is a means by which a litigant can insure against the risk of having to pay the opponent’s legal costs, where the insurance policy is taken out after the event giving rise to court proceedings, with that particular case in mind. It is a way for a person not financially eligible for legal aid, who finds a solicitor to act under a CFA, to pay a premium to an insurance company to cover the risk that s/he will be ordered by the court to pay the opponent’s costs of the litigation. 61. However ATE insurance was designed in cases where the prospects of success can be measured precisely (so that the insurance company’s risk can also be measured), eg personal injury cases, and is hardly ever available in public law litigation. This is because it can be difficult to know which party has “won” in a 17 public law case that is not primarily about damages, and so it is difficult to predict whether the claimant, the public body or neither will be ordered to pay costs. So in practice, ATE insurance is unlikely to be a solution to the problem of a non-legally aided client’s costs exposure. Protective Costs Orders 62. Sometimes the claimants in judicial review proceedings are individuals or NGOs acting in the public interest, who can raise the funds for litigation, but cannot realistically afford to meet the public body’s costs in the event of defeat. Even if such a claimant is being represented pro bono, or under a CFA, it is often the case that they will not be able to proceed with a challenge unless either the public body agrees not to seek their costs if the claim is unsuccessful or if the amount that they will have to pay towards the public body’s costs is capped at a manageable level, or even at nil. An order capping the claimant’s costs liability in this way is called a Protective Costs Order (PCO). Such orders are made on application to the court (usually at the beginning of the proceedings, before a large amount of costs have been incurred). 63. Guidance on the circumstances in which the court will make a PCO was given by the Court of Appeal in R (Corner House Research) v Secretary of State for Trade and Industry [2005] EWCA Civ 19223. The court indicated at paragraph 74 of its judgment, the principles governing the circumstances in which a PCO will be granted: “74. We would therefore restate the governing principles in these terms: 1. A protective costs order may be made at any stage of the proceedings, on such conditions as the court thinks fit, provided that the court is satisfied that: i) The issues raised are of general public importance; ii) The public interest requires that those issues should be resolved; iii) The applicant has no private interest in the outcome of the case; iv) Having regard to the financial resources of the applicant and the respondent(s) and to the amount of costs that are likely to be involved it is fair and just to make the order; v) If the order is not made the applicant will probably discontinue the proceedings and will be acting reasonably in so doing. 2. If those acting for the applicant are doing so pro bono this will be likely to enhance the merits of the application for a PCO. 3. It is for the court, in its discretion, to decide whether it is fair and just to make the order in the light of the considerations set out above”. 64. 23 A number of these criteria have been the subject of controversy, in particular, the requirement that the applicant for a PCO has no private interest in the outcome (which very much limits the use of PCOs by individuals as opposed to http://www.bailii.org/ew/cases/EWCA/Civ/2005/192.html 18 NGOs), and the statement that if the applicants lawyers are acting pro bono, it will enhance the application for a PCO. Changes on the horizon 65. The (necessarily selective) picture outlined above is a snapshot in a constantly evolving scene, which is likely to change shortly, by virtue (among other things) of: (1) (2) (3) (4) The Jackson review of civil litigation costs (January 2010)24 The response to the LSC/MoJ consultation: Legal aid: refocusing on priority cases (February 2010)25 The Government’s response to the Sir Ian Magee review of legal aid delivery and governance (March 2010).26 The (ominous) announcement on page 23 of the Government’s May 2010 publication: “The Coalition: our programme for government”27 that “We will carry out a fundamental review of Legal Aid to make it work more efficiently.” Ravi Low-Beer 14 June 2010 24 http://www.judiciary.gov.uk/about_judiciary/cost-review/jan2010/final-report-140110.pdf http://www.justice.gov.uk/consultations/docs/legal-aid-refocusing-final-response-web.pdf 26 http://www.justice.gov.uk/publications/docs/legal-aid-delivery.pdf and http://www.justice.gov.uk/news/newsrelease030310d.htm 27 http://programmeforgovernment.hmg.gov.uk/files/2010/05/coalition-programme.pdf 25 19