montana background

advertisement

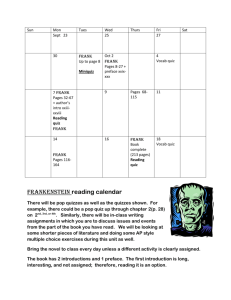

AN INTRODUCTION TO MONTANA 1948 In Montana 1948, the narrator recalls a central event of his childhood, which transformed his world and profoundly influenced his adult attitudes and life. David proudly belongs to the Hayden family, one of the most powerful and respected families in the county. When exposed to the inherent corruption at the heart of the Hayden dynasty, he is painfully forced to reassess this distinguished inheritance. His Uncle Frank, the war hero, college athlete and doctor, the true heir to the grandfather’s power and charm, but also to his crudity and ruthlessness, murders a young Sioux woman when she accuses him of sexually abusing Indian women during the course of his professional consultations. David’s father, Wes, the county sheriff, is forced to choose between his professional and moral duty and his family. The adult David, a teacher of history, is profoundly sceptical of his subject, because in choosing to do right by charging Frank, it is Wes and his family who pay the price. It is they who have to leave town and restart their lives. The Hayden myth, on the other hand, is preserved. This is not, however, simply another story of a boy’s journey from innocence to experience. The novel contains many of the features of the classic Western: the fact that it is set in Montana; the rancher/cowboy tradition embodied in the grandfather; the Indians; the sheriff and his difficult moral choice between right and might; the “showdown” between Gloria, Len and Julian’s men; David’s vision of the freedom of the wilderness; the many references to guns and so on. Watson’s theme is larger: he is, like many before him, reworking the genre. In this novel, it is the cowboys who are murdering and corrupt and it is the Indians who are on the receiving end of white abuse. It is not an accident that the adult David becomes a history teacher and has little faith in the textbooks, which, for the benefit of the next generation of Americans, extol the virtues of the frontier and underplay its corruption. Watson’s story therefore can also be read as an allegory of the American frontier experience and its subsequent misinterpretation. Larry Watson’s tale reflects the style of older American fictions, from Mark Twain to Ernest Hemingway, in that the story is character driven and the narrative is naturalistic and conventionally linear. There is a suggestion too of the romance of the old West, not only in the setting, but because his novels deal with moral issues, particularly the moral struggle of the individual. The style also borrows from later American writers, such as Raymond Carver, in the stripped down quality of the prose and the idea of the West as tarnished. To place Watson, it might be useful therefore to return to the stories of Raymond Carver. Richard Ford, who owes much of his style to Carver, often uses Montana as a setting. His novel, Wildlife, which also, by the way, deals with a young boy’s understanding of the adult world, and his short stories, Rock Springs, are set in Montana and provide another perspective on that world. Watson’s latest novel White Crosses, published in 1997, is also of interest, as its main character, Jack Nevelson, is the sheriff of Bentrock, Mercer County, but it’s now 1957. It has the same, slowly unfolding, compelling narrative as Jack confronts a moral dilemma similar to that of Wes Hayden: to use his position to protect the reputation of members of this small community or reveal the truth. Section 2. WAYS INTO THE TEXT 1. History Students need - and probably have - a rudimentary knowledge of nineteenth century American frontier history and should understand that the state of Montana belongs to that history. They need to be able to place Montana geographically and historically. The first two pages of Part One of the novel provide useful information on the geographical features of Montana and Mercer County. When outlining this history it would be useful to draw parallels with Australian history in terms of white settlement and the subsequent destruction of Aboriginal society and culture in Australia. A media file on indigenous issues may be useful as Australians face up to a similar reinterpretation of the impact of white settlement on our indigenous people. Some of this collection could be used to examine Geoffrey Blainey’s notion of the “black arm-band” approach to Australian history, which becomes particularly pertinent at the end of the novel when David talks of history as an approximation of the truth. This debate is referred to in the Activities section (page 14). Similarly, a media file on cases of sexual abuse in a professional context would enhance students’ awareness of the phenomenon. 2. The Western Students should also have some understanding of the classic Western genre in order to fully grasp the underlying theme in Montana 1948 : the reinterpretation of the American Dream. In this case it is the frontier mythology that is reworked. It would be useful therefore to have some discussion of the features of “cowboy and Indian” films and series. A screening of John Ford’s The Searchers would familiarise students with the basic themes and values of the classic Western and it includes the classic frontier interpretation of the Indian. The revisionist view of the frontier, particularly in relation to Indians can be seen in the film Soldier Blue (1974) directed by Ralph Nelson and Little Big Man (1974) by Arthur Penn. A comparison of either of these two films with The Searchers would provide students with an understanding that would enable them to place Wes Hayden’s conflict with his family in terms of the larger theme of the trashing of the frontier. The destruction of Indian culture is detailed in the book Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee by Dee Brown and their contemporary treatment is described in Black Cherry Blues, by James Lee Burke, one of a series of detective thrillers, which students might enjoy. Section 3. RUNNING SHEET MONTANA 1948 Prologue pp 1 -12 David recalls three significant images from the summer of 1948 of his father, his mother and Marie Little Soldier. Part One pp 15 –16 pp 16 –19 pp 19 –20 pp 21 –24 pp 24 – 26 pp 27 – 35 pp 35 – 38 pp 38 – 43 pp 44 – 49 pp 50 – 51 pp 52 – 54 The terrain, weather and lifestyle, post World War Two, in Mercer County, Montana is described. David describes his father, sheriff of Mercer County, affectionately, recalls his disappointment in his practical, “self-effacing” ways. The role of the grandfather in the county and his dominance of Wes is explained. The mother is introduced. David shows a liking for the wild as opposed to the orderly strictures of small town life. Marie Little Soldier and her boyfriend, Ronnie Tall Bear, are described. Marie has a severe fever, but emphatically refuses a doctor, particularly Frank, Wes’ brother. Wes and Frank exchange jokes about medicine men and Wes’ racism is described. David describes the differences between the two brothers, the comparison unfavourable to his father. He relates the grandfather’s and the county’s homecoming welcome ostensibly for all returning veterans “but really for Uncle Frank”. After Frank examines Marie, in the presence of Gail, at Marie’s insistence, he and Wes discuss the primitive attitudes of Indians to modern medicine. David’s image of Frank as hero is shattered when he overhears his mother tell his father that she has just learnt from the hysterical Marie about Frank’s consistent molestation and rape of women on the Indian reservation. Gail and Wes consult Daisy and Len McCauley separately to seek confirmation of Marie’s allegations. Wes knows that Frank is guilty, but is grappling with the moral dilemma of having to act, not only because he knows, but because he is sheriff. Part Two pp 57 – 61 pp 62 – 66 pp 66 –72 pp 73 –76 pp 77 –78 pp 79 –82 pp 82 –84 pp 84 – 85 When David runs into his father talking to Ollie Young Bear in the diner, he recognises his father’s total absorption in the case. In the backyard, David nervously queries his mother to give him entrance into their adult world, as his father pursues his investigations, interviewing Marie inside. During a visit to the grandfather’s ranch for a family dinner, David overhears his grandfather boast about Frank’s partiality to “red meat” when he was younger. David recalls his drunk father recounting an incident the night before Frank and Gloria’s wedding, when his grandfather threatened a man in a bar in Minneapolis to the amusement of his sons. On the way home from the same wedding in the train, the Grandfather lets fall a remark about Frank’s activities on the reservation. David is tortured by his love for Gloria and his current sense of shame for her. David kills a magpie with his grandfather’s automatic pistol and makes the connection between his “need to kill something” and his agitation. David comes across an argument between his father and his uncle and speculates as to the consequences of shooting Frank. On the way home, to his wife’s dismay, Wes declares that the problem has been resolved as Frank has promised to stop. pp 86 – 95 pp 95 –100 pp101 –102 August 13: Marie is found dead. David refrains from unburdening himself of his knowledge to Len McCauley, but senses from his drunken rambling about how policing is conducted in Montana, that he too knows that Frank murdered Marie. That night David tells his parents that he saw Frank leaving the house that afternoon and that Len McCauley saw him too. Wes realises he cannot avoid his duty. David’s reverie of the grieving Indians gathered on Circle Hill. Part Three pp 105 –114 pp 114 –122 pp 123 –125 pp 126-130 pp 130-140 pp 141-144 pp 145-146 pp 147-151 pp 151-154 pp 155-158 pp 159-162 Wes arrests Frank and locks him in the basement. On his way out to inform Gloria, he tells David to get Len if there’s trouble. The grandparents arrive and demand that Frank be released. The grandfather accuses Wes of being motivated by malicious jealousy. David recognises the terrible toll these events are exacting on his father. He wants his parents to provide an explanation for the confrontation with the grandfather, but his father can only advise him not to let either of his parents into their house, should they return. David’s grief for his utterly changed life is focused on the loss of his horse, Nutty, kept at his grandparents’ ranch. As he walks into town on a grocery errand for his mother the next day, David is overcome with the ignominy of being a Hayden, a name that yesterday commanded respect, if not admiration. His shame is mixed with confusion as he reflects on his Uncle Frank’s professional dealings he may have had with two of the women David sees in the street that day: Miss Schott and Loretta Waterman. Gail shoots a warning shot at a party of men sent by the grandfather to release Frank. Len arrives on the scene and using his gun as a threat persuades the men to leave. Discussion of Frank’s prosecution and the dangers of keeping him confined in the basement. Gail suggests he be released to protect her home and family and Len supports her, on the grounds of the difficulty of securing a conviction, given the power of Julian Hayden. Len intimates his support of Wes, despite pressure from Julian. David is unsettled by his father’s unstated recognition of him as an “adult.” Wes reverses his decision to release Frank, because of Frank’s lack of remorse. Frank smashes the preserves stored in the basement. Wes tells David the story of how grateful he was that Frank had saved him from a certain beating by the Highdog brothers, after Frank and his friends had taken “their” golf balls. Wes discovers Frank has suicided. David registers a feeling of relief and even love for his uncle. Epilogue pp 165-167 pp 167-169 pp 169-171 pp 172-173 pp 174-175 The manner of Frank’s death and his crimes are suppressed and Frank takes his reputation to the grave and the family’s standing is thus preserved. Its members remain unreconciled. The family move interstate to Fargo, where the father takes up a law practice. David reflects on the effects of the events of his childhood on his adult life and attitudes and describes the subsequent fate of the major players. David recalls a backyard football game with Marie and Ronnie as a time when he was “accepted ....for myself and not my blood or birthright.” When Betsy, many years later, alludes to the events in Montana at a family Thanksgiving dinner, Wes’ reaction is angry enough for David to feel the reverberation later that night. Section 4. A PERSPECTIVE ON MONTANA 1948 Montana 1948 plots the journey over one summer of a boy from a self, which is “firm and calm and malleable” to a young man with a knowledge of “the dark, flowing depths always waiting below.” At the beginning of the novel, David’s distaste for small town life rests on his belief that it belongs to the world “for the rule-makers, the order-givers, the law-enforcers.” As an adult, the sentiments are the same, (“I could never believe in the rule of law again”), but his childish unease is now a profound understanding of the powerful effects of the evil “deep in even a good heart’s chambers.” As a boy, David wanted “to grow up wild.” He “did what boys usually did and exulted in the doing” and that meant getting out of town and exploring the “alluring chaos” of the wild. David “felt a contentment outside human society that [he] couldn’t feel within it”. And, “like almost every kid in Montana”, David owned and used guns for hunting. When his grandfather hands him an automatic to take with him as he rides Nutty on the ranch, David is excited by the prospect of unlimited firepower and does not hesitate to exploit it, so that “the ground glittered with my casings and Nutty became so accustomed to the shots that he grazed right through the barrage.” David’s attraction to the wild and the masculine pursuits it offers, explains his boyish disappointment in his father, who fails to meet the masculine ideal embodied particularly in the brother, Frank. David introduces his father by mentioning his limp, earned not as a result of war, but caused by a kick from a horse. Although his father is the county sheriff, “a position with so much potential for excitement, danger, and bravery”, he avoids parading its emblems of power and authority, so that he “didn’t even look like a sheriff”, preferring “brogans and a fedora” to “boots and Stetsons” and never wearing his badge, as, being a man more concerned with everyday practicalities than image, he didn’t want its weight to tear his clothing. The comparison David inevitably draws between his father and Frank is a painful one: Frank is not only “handsome”, “a genuine war hero” and a doctor, he also “had been a star athlete in high school and college” and “was witty, charming, at smiling ease with his life and everything in it.” It’s almost as if Wes embraces the feminine, when he slips behind the crowd and, with difficulty, because of his injury, cleans up papers, as his father calls, not on Frank, but “my son” to take the accolades of the crowd at the veteran’s homecoming picnic, a virtual celebration of this particular patriarchal lineage. The core of what David perceives as this failure is Wes’ inability to evade the tyranny of the grandfather, “a dominating man who drew sustenance and strength from controlling others.” As his wife astutely understands, Wes could never achieve manhood, could never “be fully himself,” as she puts it, unless he defied the grandfather by resuming his law practice. David can record his mother’s attitudes, but, being a child, does not fully grasp their significance. Indeed, he resists her suspicion of Frank’s charm and whereas she finds the Hayden ranch ostentatious, he “loved that house”. His wistful admiration of Frank represents an attraction towards the very masculine values of those with power in the family, power which he is next in line to inherit, given Frank and Gloria’s childlessness. The irresistible sway the dynasty has over David is played out in his response to the use and possession of guns within the family. The tale David hears of his grandfather’s adventures in Minneapolis at Frank’s bachelor party, when he threatens a man in a bar with his gun, contains all the elements of the “Wild West” romance and can only reinforce the masculine insignificance of his father, the sheriff, whose gun that “looked more like a toy,” was acquired by chance from a drunk and is never worn, but stored, unloaded, in one of his dresser drawers. Despite his disapproval of such weapons, the father is unable to counter Julian’s offer to David of the automatic pistol and an unlimited supply of cartridges, when the family visits the ranch. It is when using this gun that David begins to understand the double-edged nature of those values he prizes most. When he shoots the magpie, he experiences what he normally feels when he kills something: “that extraordinary mixture of power and sadness, exhilaration and fear.” But, because he has glimpsed what lies inside the seemingly impenetrable Frank, his hero, he now begins to understand that all is not what it seems; his certainty, even of his own nature, is undone: “I realised that these strange, unthought of connections - sex and death, lust and violence, desire and degradation - are there, there, deep in even a good heart’s chambers.” It is because of the collapse of Frank as his hero that all his convictions are challenged and his world is turned upside down, even his view of his parents. Initially, his mother is the driving force for law and order, in her insistence on justice for Marie Little Soldier. Wes, the more pragmatic of the two, at first seeks to evade responsibility by hoping that Frank’s promise not to re-offend would resolve the issue. In the face of this abject cowardice, Gail insists on action. David is embarrassed by the irony of “the secretary, lecturing the lawyer, the law enforcement officer, on justice.” Although Gail confronts the grandfather’s henchmen with the gun, it is the father, finally, who has the moral strength to carry through the final confrontation, despite losing his family and inviting the community’s opprobrium. When the mother is ready to abandon the cause, it is Wes who must stand against everyone, even his wife, to exact justice. In grappling with the disjunction between reality and the ideal masculine, embodied in Frank, David feels his world is suddenly, nauseatingly less “solid, like those sewer grates you daringly walked over that gave a momentary glimpse of the dark, flowing depths always waiting below.” He now must reassess everything, including his father as the ineffectual male, for now his mother “represented practicality and expediency”, whereas, his previously “inescapably dull” father now “stood for moral absolutism.” The adult David is a man deprived of certainty, but also free of beliefs. Having seen the underbelly of “the wild”, having seen Frank buried with his reputation intact and having witnessed the price his family had to pay for standing up to lawlessness, David’s scepticism infects even his job as a teacher of history. However in laying bare the implications of his mother’s ambitions for him to be a lawyer, (“Wouldn’t it be more appropriate...for me to be elected sheriff of Mercer County, Montana and carry on that Hayden tradition?”) one conviction he does salvage is the necessity of resisting the snare of the patriarchal dynasty. Section 5. CHARACTERS A major theme in Montana 1948 is the gulf between reality and its interpretation, explored as David’s vision of Frank crumbles. His gradual disillusion so challenges his assumptions that virtually all his beliefs are reversed, including his view of himself and other people. As a way of examining this journey from innocence to experience, it would be useful to track David’s changing ideas about himself and the major characters as the events unfold. David Hayden At the beginning of the novel David finds innocent pleasure in a wilderness idyll: “I did what boys usually did and exulted in the doing: I rode horseback....I swam; I fished; I hunted....I explored; I scavenged...” . It is here that he finds a secure “self, firm and calm and unmalleable”, free of the constraints and sense of unease which he feels within “the human community”. Though it is 1948, it is Montana, and David is still able to tap into the spirit of the Wild West, the frontier, to have an intimation of the untouched wilderness before its perceived corruption by white conquest. David begins to understand his wilderness pursuits are not entirely innocent when he shoots the magpie, appropriately on his grandfather’s ranch, with his grandfather’s gun, driven unconsciously by the collapse of his idol, Frank. His urge to “kill something” reveals a half articulated vision of corruption: “these strange, unthought-of connections-sex and death, lust and violence, desire and degradation-are there, there, deep in even a good heart’s chambers.” As the full extent of Frank’s evil unfolds, the sureness David is able to feel in the wild falters. The frontier is no longer inhabited by Indians as seen in the movies; instead David dreams of the Indians he knows, mourning Marie on Circle Hill. From wanting “to be included....”, David now resents his father’s direct, inclusive gaze: “Didn’t he know - I was a child and ineligible to vote? How dare he bring me in on this now...” But his innocent security is inevitably replaced by all the ambiguity of adult awareness where “the floor beneath my feet suddenly seemed less solid, like those sewer grates you daringly walk over that gave a momentary glimpse of the dark, flowing depths always waiting below.” After his father finally declares that he cannot release Frank, David knows that ultimately even his family cannot assuage the loneliness that comes with such knowledge. The adult David is revealed as a man who believes in nothing. His view of the moral and social order is so poisoned by the events of 1948, that he even feels the teaching of history to be a compromise. Nevertheless, in exposing his mother to the true intent of her suggestion he become a lawyer, David reveals that his detachment has enabled him to avoid the fate of his father, who based his life on a lie. Wes Hayden David’s passage from innocence to experience is measured chiefly through his changed understanding of his father, who from a harmless, likeable but weak and even defeated person at the beginning of the novel, emerges as the morally strongest character. David initially describes his father affectionately, but with “disappointment”. Thus, even though his father was the sheriff of Mercer County, “a position with so much potential for excitement, danger, and bravery,” he “didn’t even look like a western sheriff”. He wore “brogans and a fedora”, instead of “boots and Stetsons”; instead of a “nickel-plated Western Colt .45 or something”, his father had a “small .32 automatic, Italian made and no bigger than your palm”, that “looked more like a toy” and was kept unloaded in a drawer at home and which the father had not even purchased, but confiscated from a “transient drunk” in exchange for the cost of a bus ticket back to his family home. David is aware that his father’s impotence comes from living in the shadow of his powerful and eminent father. Wes can never be “be fully himself”, as his wife puts it, unless he can walk away from Bentrock and his inherited job as sheriff. While Julian uses Wes as the vehicle to secure the Hayden’s influence over the county, his love and admiration is only for Frank. Next to Frank, David sees Wes as “prosaic. Oh, stolid, surely, and steady and dependable. But inevitably, inescapably dull.” This is painfully illustrated at the veterans’ homecoming picnic, where Julian turns the event into the celebration of Frank’s achievements, whilst Wes disappears to the back of the crowd to clean up, his limp rendering his stolid dependability positively pitiful. It is these very qualities, however, that enable Wes to deal with the central moral issue of the novel, when those around him seek compromise. Just as he has passively accommodated himself to his father’s ambitions, Wes seeks to avoid confronting the issue of Frank. When Wes responds to his wife’s admonitions to do something, he hopes that in speaking to Frank, the problem will resolve itself and that, “He’ll have to meet his punishment in the hereafter, I won’t do anything to arrange it in this life.” It is his wife who insists on action. She is the one wielding the gun to prevent Frank’s rescue, but she cannot sustain her principles in the face of threat. When both Les McCauley and Gloria press him to abandon the cause, Wes alone has the courage to press on. David now sees the heroic side of his father’s “prosaic” dependability, which he mistakenly interprets as a new found “moral absolutism”. The last words of the father underline David’s adult understanding of the enduring, solid values his father always possessed, but never wanted or even needed to demonstrate, prior to the summer of 1948. When David’s wife carelessly attributes those events to “Wild West” sensibilities, his angry reply, “Don’t blame Montana!....Don’t ever blame Montana!” insists that it is people, the individuals who inhabit the landscape, who alone must bear the responsibility. Gail Hayden Gail Hayden is presented as the stronger moral force in the Hayden marriage, indeed as rather straight-laced. She’s described as a “Lutheran of boundless devotion”, consistently frowns upon even the mildest blasphemies, disapproves of the ostentation of the Hayden ranch and fears for David’s love of the wild. She is the force goading her husband into action over Frank and she does not shirk from using a gun during Frank’s attempted rescue. David is forced to reassess her moral strength, when she urges Wes to release Frank, to “let him do whatever he wants to do to whomever he wants” to protect her home and family. Gail is the decisive, intelligent partner who initially is most prepared to withstand the masculine values of the “West”, but the ultimate showdown is reserved for her husband. Julian Hayden David’s grandfather embodies the guiding principle of the fading “Wild West”: power. Julian “was a dominating man who drew sustenance and strength from controlling others..... - first you master the beasts, then you regulate the behaviour of men and women”. In conquering the wilderness, morality has no place. His contempt for Wes mirrors his indifference to the rule of law. He has installed his son as sheriff simply to confirm his influence over the county and never acknowledges Frank’s activities as anything other than, as he puts it, in his typically coarse way, “a partial[ity] for red meat.” His view of the American natives is accompanied by an insensitivity towards the land demonstrated in the vulgarity of his ranch. Though built from logs, “usually symbolic of simplicity and humiliation”, its size and ostentation symbolise the corruption of the frontier. The “West” is simple a vehicle for white self-aggrandisement and domination. Although aware of his mother’s distaste for Julian’s vulgarity and overbearing demeanour, David’s attitude is more ambivalent. Thus he loves the ranch and is deeply excited when Julian, typically disregarding the feelings of David’s parents, hands him an automatic pistol to, as Julian puts it, “blast away” at “goddamn coyotes”. When returning from this shooting orgy, David even contemplates the classic frontier solution of shooting Frank, when he sees him arguing with his father on the riverbank. It is because of his grandfather’s automatic pistol, however, that David senses the profound corruption underlying his grandfather’s “Wild West” values when he shoots the magpie: “these strange, unthought-of connections - sex and death, lust and violence, desire and degradation - are there, there, deep in even a good heart’s chambers.” David becomes aware that the moral dilemma the Hayden’s are now entangled in cannot be dissolved by the mere exercise of his grandfather’s power. He tries to reassure himself that this “towering thundercloud....won’t let anything happen to his beloved son. He won’t,” but the very repetition and insistence that “he won’t” belies his conviction in Julian’s omnipotence, for it is quickly followed by doubt: ”But what if it is his other son who’s trying to do something....” David’s scepticism and even bitterness at the end of the novel comes not from understanding the evil behind his grandfather’s confident opulence and control, but from the grandfather’s insistence on the “unbridgeable gulf” between himself, the two women he dominated and David’s parents. In refusing the relationship, David’s parents have to pay the price of remaking their lives; there is no chance of David resuming anything resembling his former life. It’s this failure of reconciliation at the level of the family that fuels David’s adult scepticism for history and presumably the fictions that Americans tell each other about their past. Did the grandfather therefore ultimately win? Frank Hayden Although the central events of the novel revolve around Frank, he appears only briefly in the novel. For David he embodies everything that is desirable in a man. Frank is first introduced as “handsome”, “a star athlete” in college, “a genuine war hero”. “witty, charming, at smiling ease with his life and everything in it”. Frank is able to draw on an easy masculinity when talking to David, chatting about fishing and basketball. He even asks about the B-29 model aeroplane David is building, as he is marched down to the basement by Wes. In David’s eyes his own father is by any comparison “inescapably dull”. At the veterans’ homecoming picnic David is painfully aware that Frank is the chosen son, but as the events of the novel unfold, he begins to understand that Frank has also inherited all the corrupting qualities of the grandfather, from a tendency for coarse language to a moral carelessness which sees nothing wrong in abusing his power by molesting Indian women. When Frank suicides, David is able to feel gratitude and even “something close to love” for him, thinking that in sacrificing himself, Frank had erased the impending public scandal and that David and his family “would have [their] lives back, and if they would not be exactly what they had been earlier, they would be close enough for my satisfaction.” Of course, the adult David immediately acknowledges that this return to innocence was a childish fantasy, as it is his family, “those two people who only wanted to do right, whose only error lay in trying to be loyal to both family and justice,” who have to restart their life. Enid and Gloria Hayden Married respectively to David’s grandfather and his uncle, Enid and Gloria, barely feature in the novel, as they are appendices to these two powerful men and are doomed to live in their shadow. Len McCauley Len was effectively the grandfather’s man, in that he automatically relinquished the sheriff’s position whenever a Hayden wanted it. His drunken statement to David that being a “peace officer” under the Hayden regime in Montana “means knowing when to look and when to look away” reveals his loyalty to Julian’s frontier values. Here Len looks as though he’s stepped straight off the set of an old fashioned Western. True to the Western tradition of the hard boiled character with the heart of gold, when the heat is on, Len chooses right, even though the strain threatens to tip him back into alcoholism. (There’s even the suggestion that he’s loved his boss’ wife for years!) Thus, even though he urges Wes to take the pragmatic approach and release Frank, he admits under scrutiny from Wes that he refused to carry out the grandfather’s order to do precisely this. Marie Little Soldier Although Montana takes the revisionist side of frontier history, it could be argued that, as in positive accounts of white settlement, the Indian characters are mere backdrops to a white moral drama. Indeed, Marie is one of the few characters who remains unchanged in David’s eyes. The brief portrait the young David paints of Marie is a highly idealised one. He describes his feelings for her as love and worships her boyfriend, Ronnie Tall Bear, an athletic hero to David. Marie represents the abused Indian, brutalised and eventually murdered by white man. In the “totally free-form” football game David recalls at the end of the novel, she also represents the sentimental white vision of the innocent, untamed and unsullied primitive. David connects this play “with no object and no borders of space time or regulation” with “Ronnie and Marie’s Indian heritage.” In claiming that he briefly felt “as though I was part of a family, a family that accepted me for myself and not for my blood or birthright”, he again alludes to the notion that indigenous people have a freedom that white society cannot provide.