The Communist Manifesto

advertisement

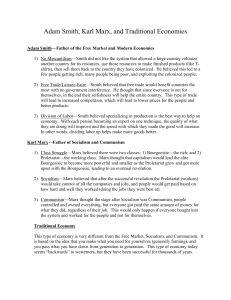

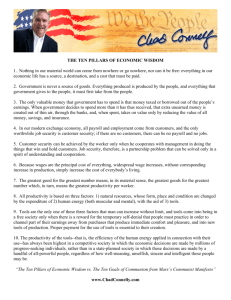

The Communist Manifesto Background: originally titled Manifesto of the Communist Party, is a short 1848 publication written by the political theorists Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. It has since been recognized as one of the world's most influential political manuscripts. Commissioned by the Communist League, it laid out the League's purposes and program. It presents an analytical approach to the class struggle (historical and present) and the problems of capitalism, rather than a prediction of communism's potential future forms. The book contains Marx and Engels' theories about the nature of society and politics, that in their own words, "The history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles.” It also briefly features their ideas for how the capitalist society of the time would eventually be replaced by socialism, and then eventually communism. The Manifesto is composed of an introduction, 3 sections, & a conclusion. Although the names of both Engels and Karl Marx appear on the title page alongside the "persistent assumption of joint-authorship", Engels, in the preface introduction to the 1883 German edition of the Manifesto, said that the Manifesto was "essentially Marx's work" and that "the basic thought... belongs solely and exclusively to Marx." Engels wrote after Marx's death: "I cannot deny that both before and during my forty years' collaboration with Marx I had a certain independent share in laying the foundations of the theory, but the greater part of its leading basic principles belongs to Marx....Marx was a genius; we others were at best talented. Without him the theory would not be by far what it is today. It therefore rightly bears his name.” Above: Marx & Engels Below: Memorial to Karl Marx in Moscow. Inscription reads: “Proletarians of all countries, unite!” Karl Marx: Born in 1818 to a wealthy middle-class German family. After graduating from the University of Berlin, he started to write for a radical newspaper, which he transferred to Paris in 1843. Here in Paris, he met Engels, who would become his lifelong friend and collaborator. In 1849, they were exiled and relocated to London where Marx began formulating his theories about social and economic activity. Marx’s theories about society, politics and the economy – collectively known as Marxism – hold that human societies progress through class struggle and capitalism was a “dictatorship of the bourgeoisie.” He predicted that capitalism produced internal tensions which would lead to its self-destruction and replacement by a new system: socialism. He argued that under socialism, society would be governed by the working class, in which he called the “dictatorship of the proletariat.” He believed that socialism would eventually be replaced by a stateless, classless society called communism. Along with believing in the inevitably of socialism and communism, Marx actively argued that social theorists and underprivileged people should carry out revolutionary action to topple capitalism and bring about socio-economic change. Following the death of his wife Jenny in December 1881, Marx developed a catarrh (blockage of mucus membranes) that kept him ill for the last 15 months of his life. It eventually brought on the bronchitis and pleurisy that killed him in London in March 1883. Revolutionary socialist governments throughout the 20th century that supported Marxism, led to the eventual establishment of socialist states in the Soviet Union (1922) and the People’s Republic of China (1945). Many labor unions and workers' parties worldwide were also influenced by Marxist ideas, while various theoretical variants, such as Leninism, Stalinism, Trotskyism, and Maoism were developed from them. Introduction The preamble to the main text of the Manifesto states that the continent of Europe fears the "spectre of communism.” Marx refers here to not only the houses of power of old Europe—the bourgeoisie—but diverse factions such as the papacy and the emerging corporate world as well. Marx declares that "It is high time that Communists should openly, in the face of the whole world, publish their views, their aims, their tendencies, with a manifesto of the party itself.” I. Bourgeois & Proletariat The first chapter of the Manifesto, "Bourgeois and Proletarians", examines the Marxist conception of history, with the initial idea asserting that "The history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles.” It goes on to say that in capitalism, the working class, proletariat, are fighting in the class struggle against the owners of the means of production, the bourgeois, and that past class struggle ended either with revolution that restructured society, or "common ruin of the contending classes.” It continues by adding that the bourgeois exploits the proletariat through the "constant revolutionizing of production [and] uninterrupted disturbance of all social conditions.” The Manifesto explains that the reason the bourgeois exist and exploit the proletariat with low wages is private property, "the accumulation of wealth in private hands, the formation and increase of capital,” and that competition amongst the proletariat creates wage-labor, which rests entirely on the competition among the workers. This section further explains that the proletarians will eventually rise to power through class struggle: the bourgeoisie constantly exploits the proletariat for its manual labor and cheap wages, ultimately to create profit for the bourgeois; the proletariat rise to power through revolution against the bourgeoisie such as riots or creation of unions. The Communist Manifesto states that while there is still class struggle amongst society, capitalism will be overthrown by the proletariat only to start again in the near future; ultimately communism is the key to class equality amongst the citizens of Europe. II. Proletarians and Communists The second section, "Proletarians and Communists", starts by stating the relationship of conscious communists to the rest of the working class, declaring that they will not form a separate party that opposes other working-class parties, will express the interests and general will of the proletariat as a whole, and will distinguish themselves from other workingclass parties by always expressing the common interest of the entire proletariat independently of all nationalities and representing the interests of the movement as a whole. The section goes on to defend communism from various objections, such as the claim that people will not perform labor in a communist society because they have no incentive to work. The section ends by outlining a set of short-term demands: 1. Abolition of property in land and application of all rents of land to public purposes 2. A heavy progressive or graduated income tax. 3. Abolition of all right of inheritance 4. Confiscation of the property of all emigrants and rebels 5. Centralization of credit in the hands of the State, by means of a national bank with State capital and an exclusive monopoly. 6. Centralization of the means of communication and transport in the hands of the State. 7. Extension of factories and instruments of production owned by the State 8. Equal liability of all to labor. Establishment of industrial armies, especially for agriculture. 9. Combination of agriculture with manufacturing industries; gradual abolition of the distinction between town and country, by a more equitable distribution of the population over the country. 10. Free education for all children in public schools. Abolition of children's factory labor in its present form and combination of education with industrial production. The implementation of these policies would, as believed by Marx and Engels, be a precursor to the stateless and classless society. In a controversial passage they suggested that the "proletariat" might in competition with the bourgeoisie be compelled to organize as a class, form a revolution, make itself a ruling class, sweep away the old conditions of production, and in that step have abolished its own supremacy as a class. This account of the transition from socialism to communism was criticized particularly during and after the Soviet era. III. Socialist and Communist Literature The third section, "Socialist & Communist Literature," distinguishes communism from other socialist doctrines prevalent at the time. While the degree of reproach of Marx and Engels toward rival perspectives varies, all are dismissed for advocating reform and failing to recognize the preeminent role of the working class. IV. Position of the Communists in Relation to the Various Opposition Parties (Conclusion) The concluding section, briefly discusses the communist position on struggles in specific countries in the midnineteenth century such as France, Switzerland, Poland, and Germany, and declares that Germany "is on the eve of a bourgeois revolution,” and predicts that a world revolution will soon follow. It then ends by declaring an alliance with the social democrats, boldly supporting other communist revolutions, and calling the proletarians to action, ending with the rallying cry of communism, “Workers of the world, unite!”