C. Wright Mills, “'Personal Troubles of Milieu' and

advertisement

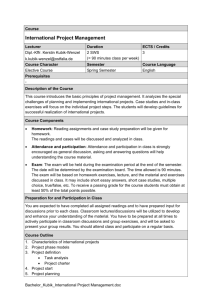

UBST 725 URBAN RESEARCH METHODS Fall 2014 Stephen Steinberg Department of Urban Studies 250-H Powdermaker Hall Office Hours: Mon 4-6 PM and by appointment Email: ssteinberg1@gc.cuny.edu 2 Goals of the Course To introduce you to the range of methodologies commonly deployed in urban research. These include macroscopic analysis, demography, intensive interviewing, survey research, participant observation, community studies, policy analysis, and evaluation research. To develop critical skills in reading and interpreting social science research, whether you encounter this research in academic settings (textbooks, professional journals, lectures), in the workplace (reports, documents), or in popular media (newspapers, magazines, television). To develop skills in laying the foundation for a research project. To become an independent and critical thinker. Course Materials All material for the course is compiled in a coursepack. Copies are available at cost. Weekly Exercises The course is organized around a series of 13 weekly readings and corresponding exercises. These exercises are designed to do two things simultaneously: 1) To introduce you to the range of methodologies commonly deployed in urban related research; 2) To sharpen your skills in reading and critical thinking. Much of the learning for the course is done though the process of completing these weekly exercises. Exercises will not be graded from week to week: it is expected that your work will improve as we go forward and you get the “hang” of the course. Early in the semester, I will give you an interim assessment of your work to make sure that you are on the right track. The exercises will be reviewed in class. Therefore, it is imperative that you complete these exercises on time and attend class consistently. Portfolio: You should make two copies of each week’s exercise—one that you will hand in at the end of class each week, and the other that you will compile in a portfolio that I will review at least twice during the semester. The Research Proposal One goal of the course is to develop skills that will prepare you to design and conduct research, culminating in a research paper. For the purposes of this course, you are asked only to design a research project—in other words, to develop the foundation and scaffolding for a research paper centered on a topic of personal interest that might be completed in another course in the department. The research proposal should conform to the following format: 3 Statement of the Research Problem: What is the overarching question or issue that defines the study? What is it that you are trying to find out? Rationale: What is the background or context of the research? What is the significance of the research for theory, research, or public policy? Review of the Literature: Place your study in the context of existing research. You can do this by identifying at least three published studies that provide background and relevance to your study. Do you propose to fill a gap left by previous research? Do you plan to challenge some finding or interpretation advanced by a previous study? Are you proposing a case study of a phenomenon that has been addressed by previous research? Generally speaking, how does your study build on previous research? Objectives: State your research objectives in more detail. What specific questions or issues govern your research? Method: What method or methods do you plan to deploy? If you plan a field study, identify the setting that is under examination, and show how the method deployed will help to shed light on the research question(s). If you plan to collect new data, identify the population being studied and how the sample will be drawn. If you plan to analyze existing data—whether from the Census or some other data source—state in detail what data are available and how they will advance the goals of the research. If you plan a more theoretically based macroscopic study, identify the research materials or data sources that fit into your analysis. Conclusion: Remember you are NOT being asked to conduct the research. However, try to anticipate the findings and the general contours of your paper. You might wish to return to the question of why and how your study is significant, either for theory, research, or public policy. I will work with you during the semester in developing this research proposal. The first step is developing a good research question—one that has clear and specific boundaries. Keep the research proposal in mind as the semester progresses, and during the second half of the course, we will have workshops on the research proposal. The research proposal is due on December 23, the last day of the final exam period. GRADES Weekly exercises will count for 80 percent, and the research proposal for 20 percent of your grade. Students who contribute substantively to class discussion will receive appropriate credit. Generally speaking, you can secure a grade of ‘B’ in the course by completing the entire series of exercises in a timely manner, together with the research proposal at the end of the semester. A grade of ‘A’ is reserved for those whose work is exemplary (with appropriate gradations in-between). 4 READING WITH AND AGAINST THE GRAIN Reading, then, requires a difficult mix of authority and humility. On the one hand, a reader takes charge of a text; on the other, a reader gives generous attention to someone else’s (a writer’s) key terms and methods, commits his time to her examples, tries to think in her language, imagines that this strange work is important, compelling, at least for the moment. David Bartholomae and Anthony Petrosky, “Ways of Reading” (2002). The passage above encapsulates the spirit and goal of the course: to learn to read—and think--both WITH and AGAINST the grain. Therefore, each week’s exercise is divided into two sections: 1. Logic of Inquiry. These questions ask you to read WITH the grain: in other words, to accept at face value the author’s intentions and authority. This involves a close examination of the logic that pertains to each step in the research process: rationale for conducting the study research question and objectives review of the relevant literature the development of an analytical framework methods deployed to acquire evidence findings interpretation and analysis of the raw evidence conclusions (which often explore the implications of the findings for public policy) 2. Critical Issues. These questions ask you to read AGAINST the grain, to critically examine the author’s knowledge claims and her or his authority and neutrality. This involves reading “behind the text” and asking critical questions: What are the subjectivities, biases, or ideological underpinnings of a particular study? Where is the researcher “coming from” in terms of his or her values or politics? Are the measures valid (in other words, do they measure what they purport to measure)? Are the conclusions fully warranted by the evidence? How might critics, approaching the study from a different standpoint, reach a different set of conclusions? What is your assessment of the strengths and weaknesses of the study under examination? The overarching goal of the course is to develop skills as an independent and critical reader. Only then are you in a position to assess whether you accept or reject an author’s knowledge claims or favor a different interpretation. 5 GLOSSARY OF TERMS Epistemology. According to the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, “epistemology is the study of knowledge and justified belief. As the study of knowledge, epistemology is concerned with the following questions: What are the necessary and sufficient conditions of knowledge? What are its sources? What is its structure, and what are its limits?” Throughout the course we will be subjecting the knowledge claims of researchers to close examination. In doing so, the course seeks to cultivate a certain “epistemological cynicism,” in the sense that we constantly ask whether or not the knowledge claims withstand close scrutiny. LOGIC OF INQUIRY. This focuses on the elements of research and the logic that permeates the research process, from the framing of research questions, to the collection and analysis of data, to the interpretation of the findings, and to assessment of the ramifications of the findings with respect to theory, research, or public policy. Research Problem: What is the question or issue around which there is uncertainty or doubt and that will be addressed by the research? Research Question: What is the central or primary research question that defines the study? Put another way, what does the researcher want to “find out”? Research Design: What methods does the researcher deploy in an attempt to come up with answers to the primary research question? What is the population or social setting under examination? How and why was it chosen? Rhetorical Frame: How does the author introduce and justify the research problem? What is the larger historical or social context that helps to “frame” the study? Significance of the Research. Why is the research significant? In other words, why is the answer to the research question worth knowing? The QMFC Grid. This is the “logical scaffolding” for virtually any study, whether it employs quantitative or qualitative methods. It challenges you to identify, in succinct language, the major elements of the research: Q: What is the primary research question? M: What methods are deployed in an attempt to answer this question? F: What are the major research findings? C: What conclusion does the study come to? What are the larger implications of the study for theory (our conceptual understanding of the problem under examination)? For research (the direction of future research)? Or for public policy (the possible public policy interventions)? Microscopic versus Macroscopic Approaches. This pertains to different “levels of analysis.” A microscopic approach focuses on individual manifestations of a particular 6 phenomenon. A macroscopic approach treats the phenomenon as a societal problem, and focuses on systemic factors that produce or sustain a particular phenomenon. For example, unemployment can be treated as an attribute of discrete individuals, and we can look at the individual correlates of unemployment, such as lack of education or of job skills. On the other hand, we can treat unemployment as an attribute of larger social aggregates or of the economy at a particular point in time. For example, unemployment might be seen as a product of deindustrialization or of economic cycles. In this instance, the unit of analysis is not the individual but factors associated with major social institutions. Thus, the thrust of macroscopic analysis is that we have to “change the system, not the individual.” CRITICAL ISSUES. Here we “read behind the text” by exploring the subtle and elusive factors that influence the interpretation and analysis of raw data. We also read “beyond the text,” by exploring factors related to the social production of research and the political uses of research. Value-Free Social Research. This “doctrine” that social science should be value-free is associated with Max Weber, one of the founders of sociology. In his famous essay on “Science as a Vocation,” Weber wrote that “the task of the teacher is to serve the students with his knowledge and scientific exposure and not to imprint upon them his personal political views." Thus, Weber enjoined social scientists to adhere to the highest standards of objectivity. However, whether objectivity is attainable or even desirable is a hotly contested issue that will come up time and again in the course. Bias in Social Research. The term “bias” does not refer only to prejudice against one group or another. More generally, it refers to notions of good and bad, right and wrong, just and unjust, which social scientists bring to their craft. Most social scientists acknowledge that value-free social science is worth striving for, even though it may not be possible to totally put aside one’s personal viewpoint and ideological preferences. Others take a more radical position, and reject objectivity as “a preposterous fallacy,” to quote Edward Carr who is on our first week’s reading. A radical view of epistemology is that truth exists only within a framework of value. This idea is not easy to grasp and will be much discussed during the semester. Note though that the point is not to expose “bias,” since it is assumed that bias exists everywhere, but rather to identify where authors are “coming from” in terms of their ideological position and/or moral judgments with respect to the subject under examination. Only by bringing this to light are you prepared to fully grasp what is being said, and to make your own determination—no doubt predicated on your own ideological bent and moral priorities—on whether you agree or disagree with the position that has been advanced in the reading. Unpacking Assumptions. You will be asked to “unpack” the hidden or embedded assumptions that lurk even behind the language we deploy. Consider, for example, “the war on terror.” What is being argued here? What are the premises of the argument, or the hidden assumptions that are embedded in this terminology? As another example, take the title of an article that we will be reading later in the semester: What Can Be Done To 7 Reduce Teenage and Out-of-Wedlock Pregnancies? What are the embedded assumptions in this construction? The idea that value assumptions are embedded in language is another difficult idea to grasp, and an even more difficult principle to apply, especially when authors hide behind the façade of objectivity. This issue will come up in each of the weekly exercises, and we have the entire semester to sort this out. Standpoint Epistemology. The idea here is that there is no such thing as “objectivity,” but rather that the social world, including even “hard facts,” will look differently and will be invested with different meaning, depending upon the “position” or “standpoint” of those who collect and/or interpret the facts. Devil’s Advocate. John Stuart Mill, the 19th century British philosopher, wrote: “The suppressed opinion might be false. Even here, though, there are advantages to letting it be aired as long and as fully as anyone wishes to air it. Even when the prevailing opinion it counters is true, it should never fear the challenge of a devil's advocate. Such a challenge can only be healthy for it.” In this spirit, from time to time throughout the course, you will be asked to assess the knowledge claims put forward by a researcher from the point of view of somebody who occupies an opposite position. The point of this is to defend one interpretation against the viewpoint of one’s intellectual or ideological adversaries, bringing to light the underlying assumptions in both cases. The Research Process. Funding. A study does not appear like the Ten Commandments as a matter of divine ordination. Much, if not most, social research is costly and depends on subsidies received from foundations, governmental agencies, or other sources. Thus, it is relevant, indeed crucial, to ask: Who funded the research? What do we know about the funding source, in terms of its politics or interests? Does this have a contaminating effect or cast a shadow of doubt on the research? Or, depending on the source, does it confer the study with legitimacy and credibility or not? Biography of the researcher(s). Edward Carr admonishes us to “know the historian before you read the history.” What can we learn (via some sleuthing on Goggle) about the researcher/author—her or his affiliations or ideological bent— that might bear on the text under examination? Note: we have to be careful not to commit the ad hominem fallacy (i.e., making judgments on the basis of the person who is advancing a knowledge claim, rather than on the basis of the rectitude of the knowledge claim itself). Even so, knowing the biography of the researcher/author may help to bring to light some of the subjectivities in the text. Venue. This refers to the place of publication. Much scholarly research is published in academic journals and books that, at least ostensibly, observe the strictures of value neutrality. Other readings we encounter through the semester were published in journals or venues that unabashedly reflect a particular political bent, whether conservative, liberal, or radical. 8 Schedule of Readings and Exercises Sept 8. Introductory class. Reading With and Against the Grain. Sept 15. The Problem of Objectivity (Exercise 1). Note: please put the exercise number on your answer sheet. Edward H. Carr. Excerpt from What is History (1965). Howard Becker. “Whose Side Are We On?” (1966). Bruce Lambert. “At 50, Levittown Contends With Its Legacy of Bias,” NY Times (1977). Sept 22. Macroscopic Analysis I (Ex. 2) C. Wright Mills, “‘Personal Troubles of Milieu' and ‘Public Issues of Social Structure,'” from The Sociological Imagination (1959). Barry Bluestone. “The Inequality Express,” The American Prospect (1994). Sept 29. Macroscopic Analysis II (Ex. 3) Edna Bonacich & Richard Appelbaum, “The Return of the Sweatshop,” from Behind the Label: Inequality in the Los Angeles Apparel Industry (2000). Oct 6. Quantitative Research I. Uses and Misuses of Polls (Ex. 4) Joel Best, “Sources of Bad Statistics” from Damned Lies and Statistics (2001). Steven A. Camarota, “An Examination of Minority Voters’ Views on Immigration.” David Leonhardt, “Yes, 47% of Households Owe No Taxes. Look Closer.” David Cay Johnston, “Breaking News: Tax Revenues Plummeted.” Diana Furchtgott-Roth, “The gender wage gap is a myth,” Wall Street Journal (7/26/12). “In Job-Placement Rates, Fuzzy Data,” Chronicle of Higher Education (7/16/12). “Perry Misleads on Jobs,” www.factcheck.org (9/2/14) “Misassigning Blame for Immigration Crisis,” www.factcheck.org (9/2/14) Oct. 13. Columbus Day—no class. Oct. 20. Quantitative Research II: Demography (Ex. 5) Susan Bianchi & Lynne Casper, “American Families,” Population Bulletin (2000). Oct 27. Quantitative Research III. Survey Research I: Research Design (Ex. 6) Johnston et al, “National Survey Results on Drug Use, 1975-2007,” Monitoring the Future (2011). 9 Nov. 3. Quantitative Research IV. Survey Research II: Data Analysis (Ex. 7) Johnston et al, “National Survey Results on Drug Use, 1975-2007,” Monitoring the Future (2011). Nov. 10. Qualitative Research I: Intensive Interviewing (Ex. 8) Waldorf, Reinarman, & Murphy: Cocaine Changes: The Experience of Using and Quitting (1991). Nov. 17 Qualitative Research II. Intensive Interviewing (Ex. 9) Michael Atkinson. “Pretty in Ink: Conformity, Resistance, and Negotiation in Women’s Tattooing,” Sex Roles (2002). Nov 24. Qualitative Research II: Participant Observation (Ex. 10) Greta Foff Paules, Excerpt from Dishing It Out: Power and Resistance among Waitresses in a New Jersey Restaurant (1991). Dec 1. Community Studies (Ex. 11) Sharon Zukin et al. “New Retail Capital and Neighborhood Change: Boutiques and Gentrification in New York City” (2009). Dec. 8. Policy Analysis (Ex. 12) Isabel Sawhill, “What Can Be Done to Reduce Teen Pregnancy and Out of Wedlock Births: A Policy Brief,” Brookings Institution (2001). Steven Cohen: “Managing Workfare: The Case of the Work Experience Program in the New York City Parks Department” (2008). Dec. 15. Evaluation Research (Ex. 13) Douglass Abbott et al, “The Influence of a Big Brothers Program on the Adjustment of Boys in Single-Parent Families,” Journal of Psychology (1997). Grossman and Tierney, “Does Mentoring Work? An Impact Study of the Big Brothers/Big Sisters Program,” Evaluation Review (1998). YOUR COMPLETE PORTFOLIO OF EXERCISES IS DUE AT THE LAST CLASS ON DEC15. THE DEADLINE FOR THE RESEARCH PROPOSAL IS DECEMBER 23 AND SHOULD BE SENT TO ME VIA EMAIL: ssteinberg1@gc.cuny.edu