The Merriam-Webster Dictionary, (Simon &Schuster, New York

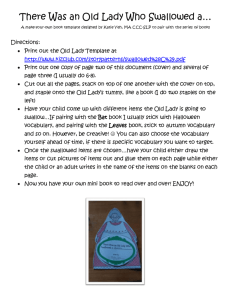

advertisement