Point One - Adult Literacy Education

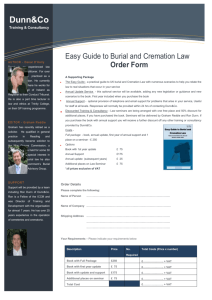

advertisement