INTRODUCTION - Continuing Education Insurance School of

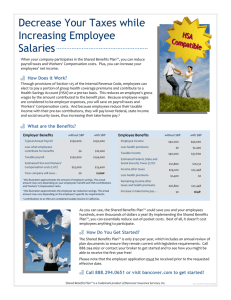

advertisement