55_CH2

advertisement

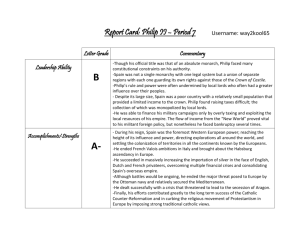

File 54 >> In Protestant countries, the political authorities were very important in implementing the ideas of Luther, Calvin, and the rest. In fact, in some respects the Protestant movement would have been much more limited were it not for the impact of politicians and government leaders. Did political leaders also have this much influence in Catholic countries, or could the pope just dictate what was supposed to happen? What role did politicians play in helping Catholicism remain such a prominent place in Christianity? >> Nick, it's absolutely the case the political leaders were as important for the Catholic reformation as were political leaders for the Protestant reformation. Church officials, even Popes, could say everything they wanted to say about what should be done. Unless the heads of Christian states, Catholic states, embraced what was said by Popes and councils, no changes would be effected. You needed the leadership of a Christian state to implement the kind of reforms that had been promulgated by Trent and by the reform-minded papacy. In order to illustrate that truth, I would like to talk about one such Catholic leader here in the 16th Century, really the dominant political figure in Europe in the course of the 16th Century, and that man is the king of Spain. His name is Philip II. Now, Philip was the son and heir of Charles V. But you recall when Charles V gave up being king and so forth, he really divided his empire into two halves. Half for his son, and another part for his brother, his brother Ferdinand who became emperor and ruler of the Hapsburg territories in Austria and places around Austria and Germany. Philip, on the other hand, the son, really received the much wealthier and more prosperous part of Charles' domains. He became not only king of Spain, but also ruler of other territories in Europe like the Netherlands, a very prosperous part of Europe there in the northern part of Europe at the mouth of the Rhine River near the North Sea. Also, parts of Italy came into Philip's hands. He also was the heir of the overseas Spanish empire which was in the process of being built up over the course of the 16th Century. So that Philip had at his disposal resources from not just Europe but from other parts of the world and was a very wealthy and powerful individual. Of course, if you rule a lot of territories, you also have a lot of responsibilities. So it wasn't simply a matter of enjoying the monarchy. In fact, in Philip's case, it was a matter of working very hard at that monarchy, and that's one of the things that we want to note about Philip, is that he had a strong character, was dedicated to his job, worked very long hours as king, and ruler of this kind of far-flung empire that he possessed. We also want to note about Philip that he was a very dedicated Catholic, very much dedicated to the Catholic religion as a result of which he was a strong opponent of Protestantism. This meant that in his own territories like Spain, he was a strong supporter of Catholic authorities, and working to snuff out heresy wherever it might appear, and Spain became a strong Catholic country, probably the strongest Catholic country of the period, the backbone of the counter-reformation. It also meant that Philip was willing to use his resources to suppress and to fight Protestantism in other places. So, for example, Philip backed the Catholic side in the wars of religion in France during the second half of the 16th Century. This, he thought, was a part of his obligation as a Christian prince or a Christian ruler. The true religion, the true church needed to be defended, and advanced, and he, as a Christian ruler, was in a position to do that. Now, one of the places within his empire that political and religious questions really came to the fore in combination and that resulted in conflict was in the Netherlands. Now, the Netherlands historically consisted of 17 different little territories. We talk about the 17 provinces of the Netherlands. By the late middle-ages, they had come to be ruled all by the same feudal nobleman, someone, for want of a better term, we can call the Duke of Burgundy. And then the Dukes of Burgundy had married into the House of Hapsburg. And by the time we get to Charles V, the Netherlands territories are all ruled by the Hapsburgs, that is the Emperor Charles V, and then they pass along to Philip II. But they have their own histories, their own traditions, and their own laws. And one of the things that they very quickly came to resent about their king, Philip, was that he seemed to be more interested in the Spanish part of his domain than he was in the Netherlands part. He appointed, for example, Spaniards as high officials within the Netherlands. And then he sought to implement policies, both tax policies and church policies, that seemed to contradict kind of the traditions and the rights and privileges of the peoples, and especially the leaders in the Netherlands. So fairly early in his reign, he began to have some problems in the Netherlands. Now, Philip, himself, was not personally present. He didn't visit the Netherlands after 1559, so he had to put into place others who kind of would rule and exercise authority in his name. And early in his reign, the regent was from the Netherlands, Margaret Parma, and she was concerned about the measure of disobedience that she was seeing. As a result, one of her advisors is said to have said, "Madam, don't concern yourself with these beggars." Well, when word of this came to the opponents, they adapted the name "beggar" as a sign of their rebellion. So beggars came to be known as the name for the rebels against Philip in the Netherlands. Now, as I indicated, this had a strong political component, and all during the reign of Philip II, those in the Netherlands who resisted his policies, resisted his rule could be doing it for simply political reasons. That is, it was a battle for their liberties, their old liberties that they had enjoyed prior to the reign of Philip II, and that meant that Catholics as well as Protestants could be a part of that rebellion. But it was also true that there was a strong religious component, and in the Netherlands, in the second half of the 16th Century, Protestantism was growing stronger and stronger, especially in its reformed variety. So here, as we have seen elsewhere, France, Scotland particularly, reformed Protestantism participated in a rebellion against monarchs, against political authorities. It was probably 1556 that the religious element started to come to the fore, and in the summer of 1556, Protestants basically -- Protestants basically went on the rampage against Catholic practice and Catholic piety in something that we call iconoclastic riots in which statues are destroyed, stained glass was destroyed, consecrated hosts were destroyed. The material things that were an essential part of Catholic worship became the object of hatred and destruction by Protestants throughout the Netherlands, but especially here. When word of this came back to Philip, he decided to take a strong measure, and he sent as governor of the Netherlands one of his strong advisors, a good military man, the Duke of Alva, and he brought with him a Spanish army. And they sought to impose obedience to the Catholic church and the king of Spain by means of force. To that end, the ruler set up a special judicial commission that Protestants nicknamed the Council of Blood because it went after many people. In fact, thousands of people were put to death by this council as rebels against the king. Well, obviously, this is going to have some effect, but it proved impossible actually to suppress the rebellion entirely. For one thing, a leader emerged who continued to kind of rally the people behind the rebellion. This was a nobleman from the Netherlands. His name was William, and his family was Orange, so it's William of Orange, and eventually, the House of Orange would produce the kings of the Netherlands, but that's a long time in the future. But really here we have kind of its origin as a special dynasty among the people of the Netherlands. So William of Orange emerged as their great leader. Sometimes he is called in history William the Silent, and that's apparently because for some period of time he was silent about his religion, and wisely so because he wanted as broad a base of support for the rebellion as he could obtain. The other thing that's noteworthy about the rebellion and why it was not fully suppressed was the fact that the Dutch, particularly on the coast, were good seamen, and they could function as pirates, or navy, whichever term you prefer, against the Spanish and the Spanish shipping. They were known as the sea beggars, and they proved a continuing thorn in the side of Philip as he tried to suppress the rebellion. It's also true that the English were willing to provide some aid and some help the rebellion. It's also true that there were even some efforts from the French in that same direction. Well, for a variety of factors, then, Philip was unable to suppress the course of the rebellion. As a matter of fact, at one point looked as if he was going to lose the entire province. But at length he found a man, the Duke of Parma, actually, another member of the Farnese family who was not only a good military man, but also a skilled diplomat. And in the 1580s the Duke of Parma actually defeated some of the rebellious forces, especially in the southern part of the Netherlands. The city of Antwerp was taken by the forces of Philip, and those southern provinces were basically kept under Spanish rule. It proved impossible, however, for Parma to gather much success in the northern part of the Netherlands, the northern seven provinces. This is where the Dutch people lived. And it was in this period that the Dutch began to implement their abilities on the seas, actually developing a commercial and trading empire by the course of the 17th Century upon which they would ultimately become one of the wealthiest parts of Europe, and Amsterdam would become one of the largest, most important cities in Europe. Well, they were able to use their resources not only on the seas, but also to actually hire soldiers to continue fighting against the forces of Philip II. The English, as I mentioned before, were also supportive of the rebellion. You will recall when we talked about Elizabeth, one of the things that Philip tried to do in the 1580s was to knock the English out of the war by sending the Spanish Armada, and eventually what he wanted to do was to send his fleet through the English Channel, they would pick up the army of Parma, take it over to England, defeat the English and so to knock the English out of the war. As we discussed previously, that didn't happen. The Spanish Armada was defeated, and that meant that the war would continue in the Netherlands the way that it had before, and, therefore, the forces of Spain never could defeat those northern seven provinces. When Philip died in 1598, the rebellion was still ongoing. It was only under his son, Philip III, that a truce was finally agreed to in 1609. By that time it was becoming pretty clear that the Netherlands were going to be in two sections, and in point of fact, Spanish rule persisted in the south for more than a century, and that southern part of the Netherlands would eventually, in the 19th Century, become the country of Belgium. It would remain Catholic. As far as the north was concerned, however, the north would eventually win its independence. The north's war for independence would continue after the truce and become part of the Thirty Years’ War, but finally in 1648 the independence of the north was recognized. We call them the United Provinces, or the Dutch Republic, and although there were a lot of different religions represented among the Dutch people, it was the reformed faith that actually became the state religion. So the revolt of the Netherlands was a failure from the standpoint of Philip. He was unable to keep the Netherlands in his domain. He was unable to keep the northern Netherlands as a part of the Catholic church. Now, in many respects, Philip's foreign adventures were failures. His side did not win in France. He wasn't able to defeat the English. The Dutch earned their independence. So in many respects his foreign policy was a failure. But there was one place in which it was a powerful success, and that was in the Mediterranean because still another problem that Philip had to address was the problem of Turkish advances from the east into the western part of the Mediterranean. The Turks were a strong power, and they had advanced up the Danube River, taking off chunks of land like Hungary, and placing that under Turkish rule, but they also advanced in the Mediterranean. Well, it was in 1571 that the combined forces of Spain and Venice and the papacy, and even the empire, those forces under the leadership of Philip's brother, Don Juan, actually defeated the naval forces of the Turks in the Battle of Lepanto just off the coast of Greece, in one of the decisive battles between the church and western Christendom. So that was an important foreign policy success during the reign of Philip II, and it was, of course, important religious overtones in the fact that the Muslims therefore would basically be kept in the eastern part of the Mediterranean instead of expanding even further west. In short then, Philip II's reign is characterized by a great deal of conflict. Much of it based in reformation and religious issues, Philip II using the resources of the monarchy to advance and to defend the interest of the Catholic church. He is really a great example of what we mean by the dependence of even the Catholic church upon the rulers of Christendom.