Final report - Learning Resource Server

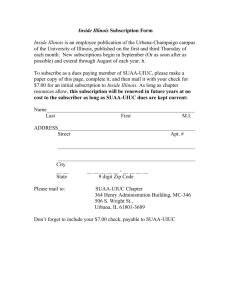

advertisement