Title Page

advertisement

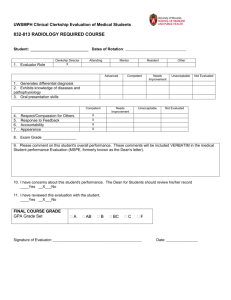

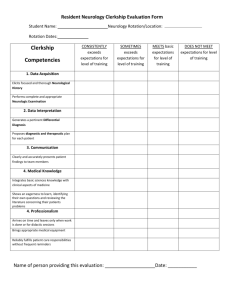

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Value of Case-Based Learning in Nuclear Medicine Clerkship CBL in Nuclear Medicine Clerkship 2 1 ABSTRACT 2 PURPOSE: Medical images, including nuclear medicine, offer powerful tools for supporting learning 3 in human morphology and physiology and understanding the nature of disease and response to 4 treatment. The purposes of this study were to create a new case-based learning (CBL) model and to 5 compare CBL and traditional instructional approach (TIA) in nuclear medicine clerkship. 6 METHODS: Internal consistency and expert validity were assessed for the instrument. A 7 quasi-experimental, two-group pretest–post-test design was used for this study. CBL allied with TIA 8 was applied to the experimental group and TIA only to the control group. Subjects were 70 9 undergraduate Year 5 medical students during the clerkship curriculum. Before and after educational 10 intervention, students were tested with the instrument. 11 RESULTS: Cronbach’s α coefficients of the instrument ranged from 0.79 to 0.95, indicating an 12 acceptable to strong internal consistency. For the expert validity, the suitability and fitness of the 13 instrument were verified. The overall score was significantly improved for experimental group (3.51 to 14 3.65, P=0.03), but not so for the control group (3.48 to 3.44, P=0.49). The experimental group also 15 showed significantly improved scores in teacher-assessment and learning satisfaction; and the later one 16 was the only domain showing a significant difference of the differences (P=0.020). 17 CONCLUSIONS: The integration of CBL allied with TIA into clinical clerkships provides medical 18 students with the opportunity to learn a nuclear medicine curriculum in an interactive and case-based 19 format tailored specifically for medical students. 20 21 Key words: Case-Based Learning, Traditional Instructional Approach, Nuclear Medicine, Clerkship, 22 Medical Curriculum 23 24 CBL in Nuclear Medicine Clerkship 3 1 INTRODUCTION 2 Imaging-guided diagnosis and therapy are indispensable tools for patient care. With the 3 technological advancements in medical imaging, including nuclear medicine, imaging guides many 4 therapeutic decisions, enables clinicians to narrow differential diagnoses, and provides clinical answers 5 [1]. Nuclear medicine is one medical specialty in Taiwan. The Nuclear Medicine physicians are not the 6 Diagnostic Radiologists. The Diagnostic Radiologist must receive the four-year training and pass the 7 certification to be a Nuclear Medicine physician and vice versa. It readily incorporates and illustrates 8 subjects that have been the cornerstone of medical education, including anatomy, physiology, and 9 pathology. Nuclear medicine education is now more integrated across the curriculum than ever. 10 However, heavy nuclear medicine physicians’ workloads, resident training, administrative duties, and 11 pressure to maintain productivity displace time and resources needed to teach medical students. The 12 diversity of how nuclear medicine is being taught within the medical undergraduate curriculum is 13 extensive with the expanding role of the nuclear medicine physician in the spectrum within the 14 medical curriculum. 15 Medical curricula seem to differ widely as to the place of and importance attached to nuclear 16 medicine clerkships. Often, it is non-nuclear-medicine clinicians to teach nuclear medicine to medical 17 students during patient rounds. Although clinicians may be knowledgeable about imaging findings 18 within their specialties, they usually teach nuclear medicine as a correlative adjunct to physical 19 findings and a patient’s clinical history. In Europe, most medical education curricula clearly 20 incorporate an opportunity to be involved in radiology clerkship, including nuclear medicine [2]. In US 21 medical schools, radiology clerkships, including nuclear medicine, are rather presented as an elective 22 and are to a lesser extent mandatory curriculum component of the medical training during the clinical 23 years [3, 4]. Positive experiences with clerkship can influence future career decisions. Early contact CBL in Nuclear Medicine Clerkship 4 1 with the radiology professional setting, including nuclear medicine, is expected to give 2 opportunities to encounter inspiring role models [1]. It is hypothesized to have an impact on opting for 3 radiology as a career perspective; especially in female students [4]. In our university hospital, nuclear 4 medicine clerkship is a mandatory component of the medical curricula for the year five medical 5 students. Of course, it is not integrated across the medical curriculum as a mandatory part for all the 6 medical schools in Taiwan. 7 With the recent advancement in educational innovations, nuclear medicine education is 8 mobilized in the most pioneering ways, stimulating a rekindled interest in the field of medical imaging. 9 The nuclear medicine physician who teaches would like students to understand the role of imaging in 10 clinical practice and learn how to order appropriate imaging workups, as well as learning and 11 improving image interpretation skills. Case-based learning (CBL) is an instructional design model that 12 is a variant of project-oriented learning. Case teaching involves the interactive, student-centered 13 exploration of realistic and specific situations. CBL develops students' skills in group learning, 14 speaking, and critical thinking. CBL was an effective, superior and student centered alternative to 15 traditional instruction approach (TIA). However, TIA using lecture based instruction is often content 16 driven, and seen as the most efficient and convenient method to offer the most information in the 17 shortest time. Little attention is given to learning problem solving, collaboration, and lifelong learning 18 skills. TIA has been shown to be less effective than other teaching methods in practical application and 19 critical thinking skills [5]. Chornery et al revealed that teaching radiology during clerkships using CBL 20 may have some advantages by learning imaging management and interpretive skills [6]. 21 During a clinical training phase, student perceptions seem to be particularly important. It has 22 been found that satisfaction with the residency experience was associated with factors that enhance 23 learning [7]. At out institution, during the clerkship, the year five medical students stay at a nuclear 24 medicine curriculum for 3 days. The related learning objectives and the schedule are clearly defined. 25 During the first clerkship day, students are given practical information and are introduced to the CBL in Nuclear Medicine Clerkship 5 1 learning objectives that have to be attained. In an effort to expose year five medical students to 2 nuclear medicine curriculum, the authors developed and used a CBL tool to teach medical students 3 nuclear medicine during clinical clerkships. This paper describes the authors' experience with the 4 development and use of CBL as an educational tool and discusses the potential benefits and drawbacks 5 of teaching nuclear medicine with CBL. 6 OBJECTIVES 7 The purposes of this study were: 8 1. to create a new instructional design model, CBL, in a nuclear medicine clerkship curriculum; 9 2. to evaluate the instrument generated by the new CBL for their reliability and validity, and 10 3. to compare the learning satisfaction and effect between CBL group and TIA group in a nuclear 11 medicine clerkship curriculum. 12 CBL in Nuclear Medicine Clerkship 6 1 METHODS 2 Design 3 An experimental, two-group pretest–post-test design was used for this study (Figure 1). CBL 4 allied with TIA was applied to the experimental group (CBL group) and TIA only to the control group 5 (TIA group). 6 Participants 7 Between September 2010 and June 2011, 6 teams of Year 5 undergraduate medical students (n = 85 ) 8 who registered for the three-day course of a nuclear medicine clerkship curriculum at a university 9 hospital in Tainan, Taiwan, participated in the study. The 6 teams of students were randomly assigned 10 to either CBL group or TIA group. Each group consisted of three teams with 10 to 12 students in one 11 team. Three teams participated in the experimental course with CBL allied with TIA, whereas the 12 other 3 teams in the control course with TIA only. One corresponding tutor with well-training on CBL 13 and TIA instruction approaches was responsible for the clerkship course. The structure of nuclear 14 medicine curriculum was described in detail in Appendix. In the present study we centered on the 15 perceived impact of the compulsory nuclear medicine clerkship for 5th year students. These students 16 have to carry out observational tasks during this period. The students have no experience of CBL 17 process in prior medical school classes. They just have the class of problem-based learning in 18 pathyophysiology two hours per week at the year-four. In CBL and in TIA, the self-study was CBL in Nuclear Medicine Clerkship 7 1 incorporated around 10% into each curriculum. One group did not know about the other group 2 with reference to CBL vs no CBL as part of the curricular format. Figure 3 shows a typical case in the 3 nuclear medicine clerkships curriculum. In TIA, this case incorporating the digital images with 4 clinical findings was presented and taught to the students. In CBL, students can request clarification 5 to better understand the context of the problem. Also a student can ultimately relate it to a real world 6 situation. Students also determined what they needed to know, as well as the resources, they should 7 use to gather the pertinent information. CBL allows our students to apply previous knowledge in 8 simulated situation. 9 Instruments 10 The instrument was a multiple-choice test that comprises 64 standardized items with 6 domains 11 including self-assessment (12 items), self-directed learning (20 items), group-cooperation (6 items), 12 teacher-assessment (3 items), learning-effectiveness (10 items), and learning-satisfaction (13 items). 13 The 6 domains reflect six foci upon the nature and value of nuclear medicine clerkship experience: (i) 14 self-assessment focus, (ii) self-directed learning focus, (iii) group-cooperation focus, (iv) 15 teacher-assessment focus, (v) learning-effectiveness focus and (vi) learning-satisfaction focus. For 16 each item, the five-point Likert scale was scored from strongly disagree (1), not agree (2), no comment 17 (3), agree (4) to strongly agree (5). At the end of instrument, students were also asked with open-ended 18 question to provide their feedbacks on the CBL allied with TIA and TIA-only programs. The 64 19 standardized questions are shown in the Appendix. 20 Validity and reliability of the Instruments CBL in Nuclear Medicine Clerkship 8 1 The validity and reliability of the instrument was assessed prior to its implementation [8]. 2 For the expert validity, the instrument was reviewed by a panel of experts, including four physicians, 3 and a professor of education, to examine the relevance and clarity of measuring dimensions and 4 instrument items. Concerning the reliability, Cronbach’s coefficient was calculated to indicate the 5 degree of internal consistency of the inventory, and the Cronbach’s coefficient was found to be 6 satisfactorily reliable for each domain (Table 1) 7 Data collection 8 A total of 70 students, including experimental groups (n = 36) and control groups (n = 34), 9 completed the instrument before and after the course. An overall response rate of 82.3% was noted, 10 with a slightly higher rate for the experimental groups (86%) than for the control groups (79%). The 11 instrument was accompanied by a letter giving background information about the objectives of the 12 study. Participation was voluntary and students were informed that neither participation nor 13 non-participation would affect their grades. One week before the intervention, an explanatory session 14 provided by the principal investigator was conducted to introduce the contents of CBL allied with TIA 15 and TIA-only program. After an explanatory session, the participants were requested to complete the 16 instrument as a pretest. Both CBL allied with TIA and TIA-only course were provided by the same 17 instructor to avoid the inter-instructor bias. The course was given for one team (experimental group) 18 after the other. After the intervention, the participants were asked to complete the same instrument as a 19 posttest. The data collection process was closely monitored by the principal investigator. 20 Statistical analyses 21 22 Statistical analyses were carried with SPSS (version 15, Statistical Package for the Social Sciences, SPSS; Chicago, IL, USA). We first examined and tested the difference in average score CBL in Nuclear Medicine Clerkship 9 1 between pre- and post- tests according to study group and selected domains. We then performed 2 the MIXED procedure, which took into account repeated measurements of test score from the same 3 individual, to test the difference of differences in two tests between the two study groups. The 4 difference in differences was also presented graphically. 5 6 CBL in Nuclear Medicine Clerkship 10 1 RESULTS 2 The instrument employed a five-point Likert scale, with six domains for self-assessment, 3 self-directed learning, group-cooperation, teacher-assessment, learning-effectiveness and learning 4 -satisfaction. For the construction of the expert validity, the suitability and fitness of all dimensions and 5 items were verified through the input of the experts. On the reliability, the Cronbach’s α values range 6 from 0.79 to 0.95, indicating acceptable to very good reliability levels, reflecting an acceptable to 7 strong internal consistency (Table 1). The Cronbach’s α coefficient for six domains were 0.79, 0.82, 8 0.88, 080, 0.91 and 0.95, respectively. The instrument was verified with adequate validity and 9 reliability. It was able to serve as an effective instrument for the measurement of CBL to a nuclear 10 medicine clerkship curriculum. 11 The number of students filling in the questionnaire was 70, a response rate of 82.3%. The 12 response rates are 86% for CBL group and 79% for TIA group. The results of tests pre- versus 13 post-intervention showed statistically significant differences on the domains of teacher-assessment (p < 14 0.05) and learning-satisfaction (p < 0.001) at CBL group (Table 2 Table 3 and Figure 2). There was one 15 statistically significant difference on the domain of self-assessment at TIA group (Table 2 Table 3). A 16 repeat measure analysis of variance, MIXED procedure, was computed by applying the 17 pre-intervention test results as a covariate, teaching methods as an independent variable, and the 18 post-intervention test as a dependent variable so as to eliminate the influence of the students’ original 19 background on the post-intervention test results. After the pre-test factor was controlled, there was a 20 significant difference on the domains of self-assessment (P <0.001) and group-operation (P <0.001) 21 between the two groups for the results of the post-intervention test. The average for the experimental 22 group was higher than that for the control group, which means that the students who received CBL 23 were performed better than those who underwent TIA (Table 2 Table 3 and Figure 2). CBL in Nuclear Medicine Clerkship 11 1 For the experimental group, the overall score significantly (p=0.03) increased from 3.51 2 points to 3.65 points, representing an increase of 4.0%. The corresponding figures for the control group 3 were 3.48 points, 3.44 points, and -1.15%. Except self-assessment domain, all other domains showed 4 improvement in score, with the greatest increase noted for learning-satisfaction domain (by 0.39 points, 5 11.4%, p=0.0001), followed by teacher-assessment domain (by 0.27 points, 8.2%, p=0.03). In the 6 control group, the only significant change was noted for self-assessment domain, for which the score 7 significantly decreased from 3.53 to 3.36 (-4.8%, p=0.02). (Table 2 Table 3) 8 9 While difference in overall score between the two groups at baseline was taken into account, the difference in overall score at the post-test tended to increase. However, such increased difference 10 was not statistically significant (p=0.101, Figure 2(g)). In fact, nearly all domains except for 11 self-assessment domain (Figure 2(a)) showed a greater increase in score for the experimental group 12 than for the control group. Nonetheless, the difference of the differences was statistically significant 13 only for learning-satisfaction domain (p=0.020, Figure 2(f)). 14 15 CBL in Nuclear Medicine Clerkship 12 1 2 DISCUSSION The results of our research are consistent with previous research about the usefulness and 3 effectiveness of pre and post-clerkship tests [9-11]. Teaching and evaluation methods related to 4 radiology clerkship have been broadly explored in the feature. Our study shows that nuclear medicine 5 clerkship for 5th year students reinforce the learning process. The result of our study indicates that 6 students perceive the clerkship as valuable for their knowledge development and skills improvement. 7 This is in line with the literature that points at the impact of attitudes on students’ performance [12]. 8 Positive attitudes towards nuclear medicine clerkship components influence considerably knowledge 9 test scores. Also graduate students who do not consider a career as a radiologist are also expected to 10 interpret radiologic images independently from the opinion and report of a radiologist’s expert [13-15]. 11 The results also indicate that our students perceived nuclear medicine clerkship as a setting to learn to 12 order and to interpret nuclear medicine images, as well as a unique possibility to attend nuclear 13 medicine patient examinations, and to have access to the different radiology software systems used in 14 clinical centers throughout the country. The latter can play very important role to enhance the appeal of 15 nuclear medicine profession. Such experiences may especially influence students with neutral or 16 ambivalent perceptions about nuclear medicine as a personal career option. 17 The enthusiastic and positive feedbacks that we have received from students completing cases of 18 CBL groups emphasize that orienting students before actual CBL process is very important. They 19 should be taught about adult learning principles and small group dynamics. This improves student 20 motivation and fosters better interaction amongst them. CBL has been shown to be an effective 21 educational tool to teach radiology [6, 16-17]. Chan et al demonstrated significant improvement in 22 posttest scores for students selected to receive CBL [16]. Chornery et al described a prospective study 23 of an online case-based teaching tool called Case Oriented Radiology Education using the CASUS 24 authoring system, incorporating text, interactive questions, hyperlinks, and multimedia in a Web-based 25 format [6]. This study supported the integration of computer-based cases for teaching radiology in the CBL in Nuclear Medicine Clerkship 13 1 2 medical school curriculum. Student feedback and our own teaching experiences have shown that nuclear medicine is best 3 learned parallel to and in conjunction with the disease processes portrayed. Our didactic lecture series 4 integrated into the forth year of medical school were poorly received by students. The year five 5 students who had already completed CBL felt that it was “too late,” and students who had not taken 6 CBL felt they did not fully understand the conditions being discussed. When the non-nuclear-medicine 7 clinicians teach nuclear medicine during patient rounds, student exposure to cases with corresponding 8 examples of imaging findings is inconsistent and unpredictable, given the diversity of clerkship 9 locations, services that students rotate through, and the different hospital populations’ students 10 encounter. When students do encounter important imaging signs on the wards, the concepts can be 11 difficult to remember without similar images and examples to highlight a learning point [18]. 12 Moreover, it may not be sufficient to teach conventional imaging vocabulary and fundamental imaging 13 concepts. Appropriate and consistent use of imaging terms on ward teaching rounds remains variable. 14 For example, incorrect terms such as dark, black, and white may be used to describe findings seen on 15 bone scan. Activity is freely interchanged with opacity. It may not be evident to students that certain 16 terms, such as hypermetabolic, cold, cool, warm, hot and signal are generally associated with specific 17 types of imaging modalities. It is important that future physicians be comfortable with basic imaging 18 terminology so that they can fully understand radiology reports and ultimately, improve patient care 19 and safety [19]. 20 Using a set of standard nuclear medicine cases for all medical students ensures that students 21 have some exposure to classic and important cases during their clerkships. Maximizing patient safety 22 also requires that medical students receive formal education about topics such as the potential risks 23 associated with radiation exposure, the use of radiopharmaceuticals, contraindications to imaging, and 24 the imaging of high-risk patient groups, such as pediatric or pregnant patients. In the era of soaring 25 health care costs and overutilization of health care resources, it is also imperative that future physicians CBL in Nuclear Medicine Clerkship 14 1 understand the studies that they will be ordering. Knowledge of study indications, study 2 limitations, cost, sensitivity, and specificity, and even a basic understanding of how studies are 3 performed can help limit wasteful utilization of health care resources. The fifth-year medical students 4 are actively engaged in the integration of clinical and imaging information, can affect students’ views 5 on the role of nuclear medicine physicians and their clinical management of patients. Furthermore, 6 diagnostic imaging can be used to support the learning of anatomy and other basic sciences in the 7 undergraduate medical curriculum. 8 Last, the standardized cases used for CBL instruction afford several educational advantages. It 9 simplifies and facilitates multiauthor contributions to each case. The feedback has enabled us to revise 10 text and images of the cases to improve the educational experience. It also enables educators to update 11 and modify teaching cases as guidelines and practices change. Nuclear medicine educators are able to 12 review and recommend a wealth of preexisting nuclear medicine educational resources. Not all of the 13 existing educational resources are suitable for medical students, and “triaging” these resources can be 14 time consuming and frustrating for students [6]. The use of CBL to teach nuclear medicine does 15 present several logistical challenges. Maintaining information in cases in the face of dynamic and 16 evolving health technology requires significant time and effort. Guidelines and practices are 17 continually changing and necessitate updates and revisions to content presented within cases. 18 Furthermore, CBL is an excellent instruction tool for teaching basic imaging concepts. Subtle 19 findings may teach with dynamically showing a positron-emission tomography (PET) study on a 20 picture archiving and communications systems (PACS) workstation. Thus, the use of CBL during 21 clinical clerkships is a positive step. The positive feedback we have received from students is 22 encouraging, but the next step of analysis will be to determine if the students retain the information 23 that CBL has taught them in the future. 24 25 Limitations CBL in Nuclear Medicine Clerkship 15 1 A number of limitations have to be mentioned in relation to this study. First, the main 2 limitations of the present study are that its sample size was small. A second limitation is that the 3 groups compared in this study were the result of a random assignment. This depended entirely on the 4 scheduling for nuclear medicine clerkship of the faculty administration. Lastly, we did not center on 5 the changes in attitudes towards nuclear medicine due to the clerkship experience. Moreover, there is 6 no consideration to CBL only, without TIA, because of heavy nuclear medicine physicians’ workloads, 7 resident training, administrative duties -----. Considering the fact that now a valid and reliable 8 instrument is available to study student perceptions in relation to six clerkship foci, future studies 9 could center on the specific impact of the clerkship experiences on changes in these affective variables. 10 11 CBL in Nuclear Medicine Clerkship 16 1 2 CONCLUSIONS Today, most teaching in nuclear medicine is still conducted by clinical practitioners that have no 3 formal expertise or training in teaching, who do not fully understand the basic nuclear medicine as 4 well as imaging techniques. In our experience, we believe that the nuclear medicine physician is 5 perhaps the best person to be involved to teach the specialty. Nuclear medicine is essential to patient 6 management as is the nuclear medicine physician integral to the teaching of this profession. Teaching 7 nuclear medicine during clerkships in this manner of CBL may have some advantages by learning 8 imaging management and interpretive skills while encountering appropriate patient groups. CBL was 9 enjoyed and embraced by the majority of students. From experience, completing CBL during clinical 10 clerkships makes students more likely to retain important nuclear medicine concepts. CBL allied with 11 TIA can be successfully implemented into a nuclear medicine clerkship curriculum. 12 13 Take Home Points 14 15 learning, group-cooperation, teacher-assessment, learning-effectiveness and learning –satisfaction 16 were significantly improved for an integrated course of CBL and TIA.The TIA only did not 17 significantly improve the overall learning outcome. 18 19 satisfaction. 20 21 medicine. 22 The learning outcomes of nuclear medicine clerkship such as self-assessment, self-directed The CBL and TIA integrated model posed the most relatively improved score on learning The integration of CBL with TIA may provide an interactive way of learning nuclear CBL in Nuclear Medicine Clerkship 17 1 REFERENCES 2 1. 3 4 1997; 12:53–6. 2. 5 6 3. Barlev DM, Lautin EM, Amis ES, Lerner ME. A survey of radiology clerkships at teaching hospitals in the United-States. Invest Radio 1994; 29:105–8. 4. 9 10 Kourdioukova EV, Valcke M, Derese A, Verstraete KL. Analysis of radiology education in undergraduate medical doctors training in Europe. Eur J Radiol 2010; 78:309-18. 7 8 Wright S, Wong A, Newill C. The impact of role models on medical students. J Gen Intern Med Roubidoux MA, Packer MM, Applegate KE, Aben G. Female medical students’interest in radiology careers. J Am Coll Radiol 2009; 6:246–53. 5. Jamkar AV, Burdick W, Morahan P, Yemul VY, Sarmukadum, Singh G. Proposed model of case 11 based learning for training undergraduate medical student in surgery. Indian J Surg 2007; 12 69:176–83. 13 6. 14 15 Chorney ET, LewisPJ. Integrating a Radiology Curriculum Into Clinical Clerkships Using Case Oriented Radiology Education. J Am Coll Radiol 2011; 8:58-64. 7. Daugherty SR, Baldwin DC, Rowley BD. Learning, satisfaction, and mistreatment during medical internship – a national survey of working conditions. JAMA 1998; 279:1194–9. 16 17 8. Li CY. Validity and reliability of an instrument. Taiwan J Public Health 2004; 23:272-81. 18 9. Novelline RA, Squire LF, Whitley JE, Written. Practical testing of medical students in radiology. 19 20 21 22 Radiology 1982; 143:795–7. 10. Blane CE, Calhoun JG, Vydareny KH. Constructing pre- and post-tests in a medical student elective. Invest Radio 1986; 21:743–5. 11. Scheiner JD, Noto RB, McCarten KM. Importance of radiology clerkships in teaching medical 23 students life-threatening abnormalities on conventional chest radiographs. Acad Radiol 2002; 24 9 :217–20. 25 12. Newble DI. Assessing clinical competence at the undergraduate level. Med Educ 1992; CBL in Nuclear Medicine Clerkship 18 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 26 :504–11. 13. Freundlich IM, Murphy WA. Medical-students who choose a radiology elective career decisions, motivations, and intentions. Acad Radiol 1995; 2:527–32. 14. Shepherd SM, Dudewicz DM, Hindo WA. Immediate and long-term effects of a sophomore radiology elective. Acad Radiol 2003; 10:786–93. 15. Blane CE, Tenhaken JD, Vydareny KH, et al. Medical-student attitudes toward radiology – a multi-institutional survey. Invest Radio 1989; 24:77–80. 16. Chan WP. Applying case-based learning to the radiology clerkship curriculum. J Med Education 2005; 9:255-61. 17. Kourdioukova EV, Verstraetea KL, Valcke M. Radiological clerkships as a critical curriculum component in radiology education. Eur J Radiol 2011; 78: 342–8. 12 18. Afaq A, McCall J. Improving undergraduate education in radiology. Acad Radiol 2002; 9:221-3. 13 19. Di lanni MJ, Walker ML. Radiology in medical school: a missing piece of the puzzle? McMaster 14 15 16 Univ Med J 2006; 3:48-50. CBL in Nuclear Medicine Clerkship 19 1 LEGENDS 2 Figure 1. The conceptual framework of the research design. 3 Figure 2. Change in the mean scores of all students in six domains (self-assessment, self-directed 4 learning, group-cooperation, teacher-assessment, learning-effectiveness and learning-satisfaction) 5 before and after the educational intervention in the experimental group and control group. Higher 6 scores indicate better performance. 7 Figure 3. One typical nuclear medicine case. A 54-year old male patient complained of severe cough, 8 hemoptysis and left upper chest tightness.18FDG PET-CT showed hot spots in left upper lung nodule 9 and mediastinal lymph nodes. 10 Table 1. The internal consistence reliability of the instrument with six domains in Cronbach’s α 11 coefficient. 12 Table 2. The difference in mean scores on the six domains in the two study groups 13 14 CBL in Nuclear Medicine Clerkship 20 1 2 3 4 Figure 1. The conceptual framework of the research design CBL in Nuclear Medicine Clerkship 21 1 Figure 2. Changes in overall and domain-specific scores between pre- and post-test for both 2 experimental and control groups 3 (a) Self-assessment p=0.675 for experiment and time interaction (d) Teacher-assessment p=0.166, for experiment and time interaction (b) Self-directed learning p=0.210, for experiment and time interaction (e) Learning-effectiveness p=0.636, for experiment and time interaction (c) Group-cooperation p=0.288, for experiment and time interaction (f) Learning-satisfaction p=0.020, for experiment and time interaction (g) Overall p=0.101 for experiment and time interaction Experiment CBL in Nuclear Medicine Clerkship 22 Control 1 2 CBL in Nuclear Medicine Clerkship 23 1 Table 1. Mean score and the internal consistency reliability for the six domains of the instrument Cronbach’s α Mean (SD) Self-assessment 0.79 3.77 (1.26) Self-directed learning 0.82 3.49 (1.00) Group-cooperation 0.88 3.51 (0.88) Teacher-assessment 0.80 3.51 (0.76) Learning-effectiveness 0.91 3.80 (0.58) Learning-satisfaction 0.95 3.92 (1.32) Domains 2 3 4 CBL in Nuclear Medicine Clerkship 24 1 Table 2. The difference in mean scores on the six domains in the two study groups Domains Experimental group (n=36) Self-assessment Self-directed learning Group-cooperation Teacher-assessment Learning-effectiveness Learning-satisfaction Overall Control group (n=34) Self-assessment Self-directed learning Group-cooperation Teacher-assessment Learning-effectiveness Learning-satisfaction Overall 2 *p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001 3 Numbers in parenthesis are SD. 4 Pre-test Post-test Difference p-value 3.82 (0.41) 3.38 (0.23) 3.36 (0.40) 3.29 (0.32) 3.65 (0.50) 3.77 (0.69) 3.48 (0.36) 3.52 (0.37) 3.56 (0.38) 3.78 (0.48) -0.05 (0.58) 0.10 (0.31) 0.16 (0.38) 0.27 (0.36) 0.13 (0.49) 0.37 0.51 0.66 0.03* 0.16 3.43 (0.55) 3.51 (0.23) 3.82 (0.42) 3.65 (0.21) 0.39 (0.48) 0.14 (0.22) 0.0001** 0.03 3.53 (0.49) 3.42 (0.29) 3.17 (0.34) 3.35 (0.54) 3.52 (0.66) 3.36 (0.55) 3.38 (0.27) 3.18 (0.37) 3.38 (0.49) 3.59 (0.68) -0.17 (0.52) -0.04 (0.28) 0.01 (0.35) 0.03 (0.52) 0.07 (0.67) 0.02* 0.51 0.89 0.78 0.37 3.67(0.58) 3.48 (0.35) 3.66 (0.60) 3.44 (0.38) -0.01 (0.59) -0.04 (0.37) 0.88 0.49 CBL in Nuclear Medicine Clerkship 25 1 Appendix 2 The 64-item scale. self-assessment (12 items) 1 Please rate yourself from being quiet to being lively. 2 Please rate yourself from being absently minded to being minded. 3 Please rate yourself from being calm to being restless. 4 Please rate yourself from listening to exploring. 5 Please rate yourself from obeying to leading somebody. 6 Please rate yourself from thinking to operating. 7 Please rate yourself from describing something by words to by image. 8 Please rate yourself from reasoning to acting on instinct. 9 Please rate yourself from solving problems yourself to discussing with others. 10 Please rate yourself from solving problems passively to doing actively. 11 Please rate yourself from solving problems in a daze to exploring them. 12 Please rate yourself from solving problems by systematic processing to being tentative. 3 self-directed learning (20 items) 1 I like group learning. 2 I like to share knowledge and experience with the classmates. 3 I listen to other people's ideas and suggestions. 4 I accept the comments of somebody. 5 I am an emotional person. 6 I am able to think rationally. 7 I can talk to strangers. 8 I cannot express myself well. 9 I trust my own judgment. 10 I understand my personality. 11 I am good at analyzing and reasoning. 12 I am good at integrated coordination. 13 To stimulate more ideas with the students worked in a group. 14 I am confident with regard to make a presentation. CBL in Nuclear Medicine Clerkship 26 15 I often have no idea how to talk in group discussion. 16 I am always getting distracted in group discussion. 17 I often cannot get the currently focused element in group discussion. 18 I usually do not know how to ask questions in response to the classmate’s oral presentation. 19 I am usually skeptical about the classmate’s report. 20 I often cannot find the right information to make the oral presentation. 1 group-cooperation (6 items) 1 The frequency of the group discussion is appropriate. 2 The frequency of everyone to make an oral statement is appropriate in group discussion. 3 The number of members in one group is appropriate. 4 A small number of classmates have the much time to talk in group discussion. 5 The contents are not focused in group discussion. 6 It is efficient for the analysis of the problems in group discussion. 2 teacher-assessment (3 items) 1 The teacher in the class is serious in group discussion. 2 The teacher often interrupts the discussing process in group discussion. 3 The teacher has good interaction with students in group discussion. 3 learning-effectiveness (10 items) 1 CBL is better than TIA. 2 CBL process enabled you to access a greater variety of resources. 3 CBL is an efficient learning method. 4 You can achieve the intended learning objectives in each group discussion. 5 CBL process enabled you to easily understand the problems of every case. 6 The comments of classmates had great reference value on analyzing the problems. 7 CBL process improved your ability to solve professional problems. 8 CBL process is efficient for integrating the important information. 9 CBL process improved your interpersonal skills to solve problems by teamwork. 10 CBL process has improved your clinical reasoning skills and clinical competence independently. 4 learning-satisfaction (13 items) CBL in Nuclear Medicine Clerkship 27 1 CBL process is a challenge for me in this semester. 2 CBL method improved your ability of gathering information , organizing them and store in usable form for future use 3 CBL method has motivated me to learn 4 After CBL method, I am confident for my analysis work. 5 After CBL method, I have better skills to solve the problems. 6 Overall during our discussion, faculty I approached was very helpful and the discussion has helped me in learning. 7 After CBL method, I can find out the reasons to support or oppose the problems. 8 Overall during our discussion, I learned how to lead the team to do the discussion. 9 Overall during our discussion, I learned how to do self-integration and construct knowledge by myself. 10 I have better interpersonal skills in terms of listening, giving, and receiving criticism etc. 11 After CBL method, I learned how to do more in-depth data analysis. 12 I find that the CBL process has changed the way I study. 13 Please rate the CBL method. 1 2 3 4 CBL in Nuclear Medicine Clerkship 28 1 2 3 Appendix Case-Based Learning Process standardized nuclear medicine cases for medical students 4 Prepare case history. After they hypothesized, they raised learning issues Students develop the hypothesis and decide about learning issue. Chairman allotted various learning issues amongst themselves. The students can have multiple sessions, some of them can be private. Intersession period Students used all the resources, including library, Internet, faculty from different fields to form a concise knowledge about the topic. Students reported the problems solved to the group. Tutor refined the knowledge in case required.