discussion paper knowledge mobilization

Knowledge Mobilization:

A preliminary Conceptual Framework

A Draft Background Paper

Prepared for

The Task Force on

Building Disability Community Organizations’

Policy Research and Knowledge Mobilization Capacity

Prepared by

Claire Atherton, Researcher

The Canadian Association for Community Living

March 2006

Knowledge Mobilization

Making the leap from research into policy change is the goal of Knowledge Mobilization ; however, there are a number of steps between knowledge and practical change that require attention in the process of mobilizing knowledge. The concept of knowledge mobilization involves creating knowledge, from both research and solutions developed from every day problem solving, which is accessible to a wide audience and is actively applied by policy makers and practitioners. Daryl Rock defines knowledge mobilization as “Getting the right information to the right people in the right format at the right time so as to influence decision making.” 1

According to Rock “knowledge mobilization is ongoing throughout the research process, involves shared decision making and multiple uses for the research, multiple audiences, and has a broad reach.” 2

Two central knowledge mobilization activities include actively promoting the sharing of knowledge, resources and expertise between universities and organizations in the community and policy makers, and reinforcing community decision-making and problem-solving capacity. Overall, he argues that in order to effectively mobilize knowledge these strategies must “speak to the unique cultures of academics, mental health practitioners, public policy-makers, and people who belong to diverse culturallinguistic communities.” 3

Knowledge mobilization is a concept that encompasses a number of other models of knowledge use and policy change including Knowledge management, Knowledge Networking, Communities of

Practice, Knowledge Brokering, Knowledge Translation and Utilization.

Each of these concepts is interrelated, overlapping, and is distinguished by which step between knowledge and change in practice that each focuses on. Together, the application of these elements can make an effective model of knowledge mobilization. The following sections of this document will discuss each of these elements, their definition, and their relevance to the goal of knowledge mobilization and their applicability to the current project.

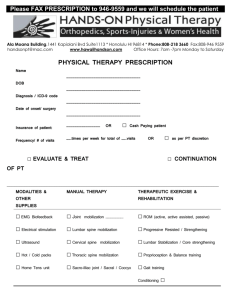

Knowledge Mobilization

Applying Knowledge at the site of practice

Policy Decision Makers

Knowledge

Management &

Internal Culture

Change

Knowledge

Networks &

Communities Of

Practice

Knowledge

Utilization

Sharing Information &

Building Social Capital

Knowledge

Translation

Employers

Local & National

Governments

Knowledge Brokering

Organizations:

Knowledge from

Problem Solving

& Research

Across Stakeholders

Community

Members

Researchers

Civil Service

Civil Society

Health Care

Practitioners

Policy Change

Service

Providers

- 1 -

Problem Solving

Capacity:

Improved ability to meet objectives and maximize the application of the knowledge of individuals

Knowledge

Creation:

Members of an organization solve new problem or solve smaller parts of a larger problem

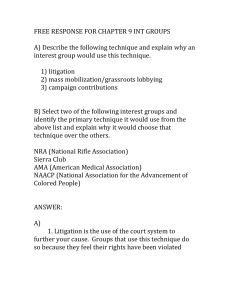

Knowledge Management

Knowledge Management within individual organizations is an important first step in the knowledge mobilization process.

Sherkin argues that improving the knowledge management infrastructure within organizations

Knowledge Management

Internal Knowledge

Management Networks that participate in knowledge networks and other knowledge mobilization strategies is essential to an effective network and, in the end, to knowledge mobilization.

4

In order for organizations within a community, such as the disability community, to share and mobilize knowledge effectively and create

Dissemination:

Share knowledge with members of the organization and stakeholders affected by the problem.

Preservation:

Document the description of the problem and its solution. policy change it is imperative that knowledge be managed effectively within the constituent organizations.

Creech describes internal knowledge management networks , a model of knowledge management that focuses on the internal knowledge and problem solving capacity of organizations. These internal networks “evolve through the thematic mapping of expertise within an organization, combined with the creation of appropriate environments for knowledge sharing.” These networks are primarily internal and formed for the purpose of improving the ability of an organization to meet its objectives and maximize the application of the knowledge of individuals.

5

A culture of knowledge sharing within organizations is central to knowledge management and creating the appropriate environment for knowledge sharing. A culture of knowledge sharing must be fostered by managers and knowledge brokers through positive reinforcement of knowledge sharing between members of an organization.

According to Salisbury, knowledge management occurs in an ongoing cycle where each knowledge management phase provides input for the next phase, creating an ongoing cycle. The first phase is the creation of new knowledge which happens when members in the organization solve a new problem, or when they solve smaller parts of a larger problem. The next phase is the preservation of this newly created knowledge through documenting the description of the problem and its solution. This phase feeds into the next, dissemination phase , which includes sharing new knowledge with other members of the organization and with the stakeholders affected by the problems that are solved.

Disseminated knowledge then becomes an input for solving new problems in the next knowledge phase increasing an organization’s ability to solve problems overall.

6

Knowledge management is an important part of knowledge mobilization because both knowledge networks and knowledge sharing rest on the ability of the organizations within a community to identify, document, and disseminate knowledge acquired through problem solving and through research. However, Sherkin points out that “Many civil society organizations do not possess standardized internal procedures for communications. Thus, knowledge networks must explicitly address the importance of building communications capacity within member networks and to coordinate their collective engagement efforts.”

7

Knowledge management requires cultural changes and resource investment within organizations, which, once made, can enable organizations to share knowledge with each other more and policy decision makers in local, provincial and federal governments.

- 2 -

Knowledge Brokering:

According to the Canadian Health Services Research Foundation, Knowledge Brokering is a type of activity that focuses on identifying and bringing people interested in an issue together, who can then help each other develop evidence-based solutions to the problems in the current environment.

Knowledge brokering is generally conceived of as being preformed by individuals whose job consists of facilitating knowledge transfer and communication between parties to support evidence based decision making. The role of the knowledge broker is to help “build relationships and networks for sharing existing research and ideas and stimulating new work.” 8

Knowledge brokers are an essential element in the development of a self-perpetuating knowledge creation cycle within a community. They are also essential for the purpose of ensuring knowledge is made available to those who can most effectively use it and supporting the necessary cultural change within an organization for knowledge management and sharing.

According to Gold and Villeneuve, Knowledge Brokering involves “Finding the right people and linking them; helping to set agendas and facilitating their interactions; understanding the realities of others involved in different spheres but interested in the same issue; creating a common language and frame of reference; and helping to establish realistic expectations, roles and responsibilities.” 9 Overall, the true goal of knowledge brokering is to bridge communities, which requires a solid understanding of all the relevant environments of participants and stakeholders, whether these be in the context of policy making, service consuming, researching or advocating.

10

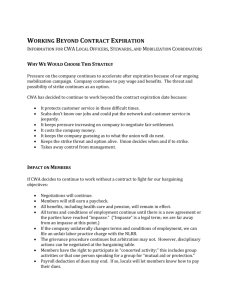

Knowledge Networking:

Creech provides a clear definition of Formal Knowledge Networks

; “(they) consist of groups of expert institutions that work together on a common concern, strengthen each other’s research and communications capacity, share knowledge bases and create solutions that satisfy the needs of target decision makers at the national and international level.”

11

The kinds of institutions found in these networks can include “local and national governments, community members, service sector, civil society, academics/researchers and employers.” 12

Howard Clark of the International Institute for

Sustainable Development has identified a number of ideal characteristics of knowledge networks that have been successful in Canada in the past. These include:

1. Their main purpose is to create and

Research

Organizations

Advocacy

Organizations

Service

Providers and

Practitioners disseminate knowledge for use beyond the membership of the network;

2. Their structure and operation are designed to maximize the rate of

Internal

Knowledge:

Research &

Problem Solving knowledge creation;

3. The network must provide recognizable direct benefits to all participants;

Universities

Policy Decision

Makers: Local &

National

Government

Community

Members &

Service

Consumers

4. There is a formal organization and well-defined management structure;

5. Participation is by invitation, based on criteria of merit or peer review;

6. There is a well-developed communications strategy; and

7. The network results in a reduction of boundaries between sectors such as

- 3 -

universities and industry.

13

The goal of such networks is to create relationships, trusts and knowledge sharing between members for the purpose of developing “more inclusive economies, societies and institutions of governance.” 14

Karmali has identified five key factors that enable knowledge networks to move from functional to successful. “These include (i) trust, (ii) sociability, (iii) shared ownership, (iv) perceivable benefit, and

(v) room for creativity/‘creative chaos’.” 15 Knowledge networks are a particularly important element in the knowledge mobilization project because the relationships on which these networks are founded are also a source of credibility and influence in the policy making process. The networks also help to create a self propelling knowledge creation process that constantly moves foreword, and avoids the tendency to reinvent the wheel, because of the multiple sources of inputs as well as the ability of various organizations and institutions to benefit from, learn, and communicate about the knowledge acquired by others in the same field.

Communities of Practice:

Communities of Practice are similar to knowledge networks but are less formal and institutionalized. They tend to work within organizations but also within a general field or community.

Communities of practice consist of “informal clusters and networks of employees who work together sharing knowledge, solving problems and exchanging insights, stories and frustrations.” 16

According to

Lesser and Prusak, communities of practice “are the major building blocks in creating, sharing and applying organizational knowledge.” 17

They are valuable because they contribute to an organizations’ social capital , which is the basis of knowledge sharing and knowledge mobilization. Social capital consists of a number of resources which are at the disposal of the individuals within a community of practice and the organizations they are a part of. These resources include “common identity, familiarity, trust, and a degree of shared language and context among individuals.” 18

The result of having these resources is that it takes less time to locate experts in a field, validating expertise is swifter, and it creates more secure foundations for agreements made between organizations and between individuals within organizations, all of which enable an organization to better manage its knowledge resources.

19 addition, according to Lesser and Prusak, “By being able to bring people together to create and share

In relevant knowledge, the community creates the condition where individuals can “test” the trustworthiness and commitment of other community members.” 20

Lesser and Prusak suggest a number of rules of thumb in supporting communities of practice and the social capital they entail:

Identify communities of practice that influence critical goals within the organization.

Provide communities with the means to meet face-to-face.

Provide tools that enable the community to identify new members and maintain contact with

existing members. Technology can play an important role in supporting communities of practice.

Identify key “experts” within the community and enable them to provide support to the larger group.

Remember that the capital, in social capital, implies an investment model with an expected return.

21

Knowledge Utilization:

Knowledge Utilization focuses on understanding the relationship between the research and knowledge of advocacy and research organizations and policy change. Research in knowledge utilization attempts to address the question “Why are some of the ideas that circulate in the research/policy networks picked up and acted on, while others are ignored and disappear?” 22 Research in this area attempts to understand the non-linear relationship between research findings and the decisions made by policy makers. According to Garret and Islam “The complexity of the policy process and the general nature of much policy research make it difficult to attribute policy decisions or policy outcomes

- 4 -

to specific research findings. Policy research can have significant impact on policymaking, just not necessarily on discrete choices nor in the linear sequence that researchers and donors would like to see.” 23 Although the general consensus in the literature is that the relationship is usually unsatisfactorily non-linear, that is researchers are usually disappointed to find that research can be translated or used in unintended ways, it does nevertheless have an important impact on the context in which decisions are made by policy makers. Maja de Vibe, Ingeborg Hovland and John Young have identified a combination of several determining influences, which can broadly be divided into three areas: “The political context; The actors (networks, organisations, individuals); and the message and media.” 24

Because the factors that policy makers base their decisions on come from multiple sources, information acquired through research may not be directly translated into policy. Instead, Garret and Islam argue,

“research information provides a diffuse ‘enlightenment’ function, providing an understanding and interpretation of the data and the situation that is critical to the policy decision.” 25 They argue that over time research contributes to conventional wisdom and “shapes people’s assumptions about how things work, about what needs to be done, and what solutions are likely to achieve desired ends.”

26

Maja de Vibe, Ingeborg Hovland and John Young point out this kind of diffuse influence is central to the knowledge mobilization capacity of informal networks, which can become

Rather a potent means of challenging public management through generating multiple unofficial and creative policy ‘interpretations.’ Over time these informal interpretations become institutionalised, but once they are recognised as official policy, the networks will already have started generating new unofficial ideas.

27

It is in the realm of informal influence and the ability to propose alternative, creative solutions to problems that knowledge networks find the ability to mobilize their knowledge. According to Garret and

Islam “Powerful interest groups need not be rich or large… the power of an external interest group is determined by its control over resources and access to information, its skill in using these advantages, including generation of media coverage, and other players’ perceptions of these characteristics, including perceptions of their credibility.” 28

It is therefore imperative that civil society organizations work together to network knowledge, leverage their information, research, and credibility in order to influence policy effectively in a political context. “Evidence must be relevant, appropriate and timely, in a specific social, political and economic context.” 29

In addition, fundamental to the influence of civil society organizations’ influence is “the position that a CSO holds within a particular political system, and its relationships with other actors, affects the ways it can use evidence and the likelihood of it achieving policy influence.” 30

Knowledge networking, communities of practice, knowledge management, brokering, and translation can all contribute to increasing the influence of the knowledge produced by civil society organizations. Developing relationships with actors on the ground who implement policy, with other organizations with similar goals, and with policy makers, can be made more effective when combined with an understanding of the policy decision-making.

Knowledge Translation:

According to the National Centre for the Dissemination of Disability Research, Knowledge Translation is a relatively new term that attempts to address the underutilization of evidence based research in systems of care. Knowledge translation attempts to address what “is often described as a gap between

‘what is known’ and ‘what is currently done’ in practice settings.” 31

The Canadian Institutes for Health

Research (CIHR) defines Knowledge Translation as “the exchange, synthesis, and ethically-sound application of knowledge—within a complex set of interactions among researchers and users—to accelerate the capture of the benefits of research for Canadians through improved health, more effective services and products, and a strengthened health care system.” 32

Knowledge translation is distinguished from dissemination or diffusion because it is more focused on the quality of research and its

- 5 -

implementation within a system, such as healthcare. “KT requires coordination and process improvement amongst a complex system to influence behavior change and patient outcomes” (my emphasis).

33 Knowledge translation is an active strategy aimed at facilitating the processes between the knowledge creation and its application in actual settings for the purpose of bringing about beneficial outcomes in the relevant system and wider society. Knowledge translation occurs “in the site of practice and its social, organisational, and policy environment rather than in learning situations” 34 such as universities. This model focuses not only on those people who apply knowledge themselves (such as health care practitioners) but also includes the persons impacted in the practices to be changed, (such as patients, or care receivers), as well as policy makers.

35

This is the ultimate site of knowledge mobilization. Because there is often not only a disconnect between research and practice, but also between policy and practice, knowledge translation techniques can help mobilize knowledge to bridge both of these gaps. Ultimately, changes in knowledge and policies will not be effective or relevant if the people on the ground in the site of practice have not adopted the new beliefs and practices resulting from the research and problem solving of advocacy, and research organizations, and members of the community.

1 Rock, Daryl Chairman, Ontario Neurotrauma Foundation “Knowledge Mobilization Presentation” (PDF 229Kb) http://www.onf.org/knowledge/pdf/knlg_mob_frmwrk.pdf

2 Rock, Daryl. ONF.

3 Community University Research Alliance (CURA) . Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC). http://www.crehscura.com/knowledge_mobilization.php

4 Sherkin S. pg 9. “Canadian Knowledge Networks for Inclusion: Reflections and Strategies” Canadian Association for

Community Living.

5 Creech H. 2001a. pg8. Strategic Intentions: Principles for Sustainable Development Knowledge Networks International.

Institute for Sustainable Development.

6 Mark, W. Salisbury. 2003. “Putting theory into practice to build knowledge management systems”

Journal of Knowledge Management, Vol. 7, Is: 2, , pp. 128 - 141

7 Sherkin S. pg 9.

8 Canadian Health Services Research Foundation. 2003. p ii. The Theory And Practice Of Knowledge Brokering In Canada’s

Health System: A Report Based On A CHSRF National Consultation And A Literature Review . Available online at: http://www.chsrf.ca/brokering/pdf/Theory_and_Practice_e.pdf

9 Gold I. and J. Villeneuve. 2003. Busting the Silos: Knowledge Brokering In Canada.

Powerpoint presentation from the 5 th

International Conference on the Scientific Basis of Health Services, Washington, DC., Canadian Health Services Research

Foundation. available online at: http://www.chsrf.ca/brokering/pdf/time_to_build_e.pdf

.

10 Gold I. and J. Villeneuve. 2003.

11 Creech, H.

2001b. Measuring while You Manage: Planning, Monitoring And Evaluating Knowledge Networks. Version

1.0.

Winnipeg: International Institute for Sustainable Development. Quoted in Sherkin S. “Canadian Knowledge Networks for Inclusion: Reflections and Strategies” Canadian Association for Community Living.

12 Sherkin S. pg 5.

13 Clark, Howard. 1998. pg1. Formal Knowledge Networks: A Study of Canadian Experiences.

International Institute for

Sustainable Development. Available online at: http://www.iisd.org/pdf/fkn.pdf

.

14 Sherkin S. pg 5.

15 Karmali, F. (2003). pg. 21.

Knowledge Sharing: CACL’s Initiative to Leverage Experiences and Expertise

. Toronto.

Quoted in Sherkin S. “Canadian Knowledge Networks for Inclusion: Reflections and Strategies” Canadian Association for

Community Living.

16 E Lesser, and L Prusak. White Paper: Communities Of Practice, Social Capital And Organizational Knowledge

IBM Institute for Knowledge Management, Cambridge, MA. 1999 - providersedge.com http://www.providersedge.com/docs/km_articles/Cop_-_Social_Capital_-_Org_K.pdf

17 E Lesser, L Prusak. 1999.

18 E Lesser, L Prusak. 1999.

- 6 -

19 E Lesser, L Prusak. 1999.

20 E Lesser, L Prusak. 1999.

21 E Lesser, L Prusak. 1999 .

22 Maja de Vibe, Ingeborg Hovland and John Young. 2002. “Bridging Research and Policy: An Annotated Bibliography”

Working Paper 174 Results of ODI research presented in preliminary form for discussion and critical comment. http://www.odi.org.uk/publications/working_papers/wp174.pdf

23 James L. Garrett and Yassir Islam. “Policy Research and The Policy Process: Do The Twain Ever Meet?” IIED Gatekeeper

Series vol. 74. http://www.iied.org/NR/agbioliv/gatekeepers/documents/GK74.pdf

24 Maja de Vibe, Ingeborg Hovland and John Young. 2002.

25 James L. Garrett and Yassir Islam.

26 James L. Garrett and Yassir Islam.

27 Maja de Vibe, Ingeborg Hovland and John Young. 2002.

28 James L. Garrett and Yassir Islam.

29 Pollard, Amy and Julius Court. 2005. “How Civil Society Organisations Use Evidence to Influence Policy Processes: A literature review.” Overseas Development Institute. http://www.odi.org.uk/publications/working_papers/wp249.pdf

30 Pollard, Amy and Julius Court. 2005.

31 National Center for the Dissemination of Disability Research (NCDDR). 2005. “What is Knowledge Translation?”

Technical Brief Number 10. Available online at: http://www.ncddr.org/du/products/focus/focus10/Focus10.pdf

32 NCDDR. 2005.

33 NCDDR. 2005.

34 Dave Davis, Mike Evans, Alex Jadad, Laure Perrier, Darlyne Rath, David Ryan, Gary Sibbald, Sharon Straus, Susan

Rappolt, Maria Wowk and Merrick Zwarenstein. 2003. “The Case For Knowledge Translation: Shortening The Journey From

Evidence To Effect” in

BMJ 2003;327;33-35. Available online at: http://bmj.bmjjournals.com/cgi/reprint/327/7405/33?maxtoshow=&HITS=10&hits=10&RESULTFORMAT=1&author1=dav is&author2=evans&andorexacttitle=and&andorexacttitleabs=and&andorexactfulltext=and&searchid=1081973199166_8056

&stored_search=&FIRSTINDEX=0&sort

35 Dave Davis, Mike Evans, Alex Jadad, Laure Perrier, Darlyne Rath, David Ryan, Gary Sibbald, Sharon Straus, Susan

Rappolt, Maria Wowk and Merrick Zwarenstein. 2003. “The Case For Knowledge Translation: Shortening The Journey From

Evidence To Effect” in BMJ 2003;327;33-35. Available online at: http://bmj.bmjjournals.com/cgi/reprint/327/7405/33?maxtoshow=&HITS=10&hits=10&RESULTFORMAT=1&author1=dav is&author2=evans&andorexacttitle=and&andorexacttitleabs=and&andorexactfulltext=and&searchid=1081973199166_8056

&stored_search=&FIRSTINDEX=0&sort

- 7 -