doc

advertisement

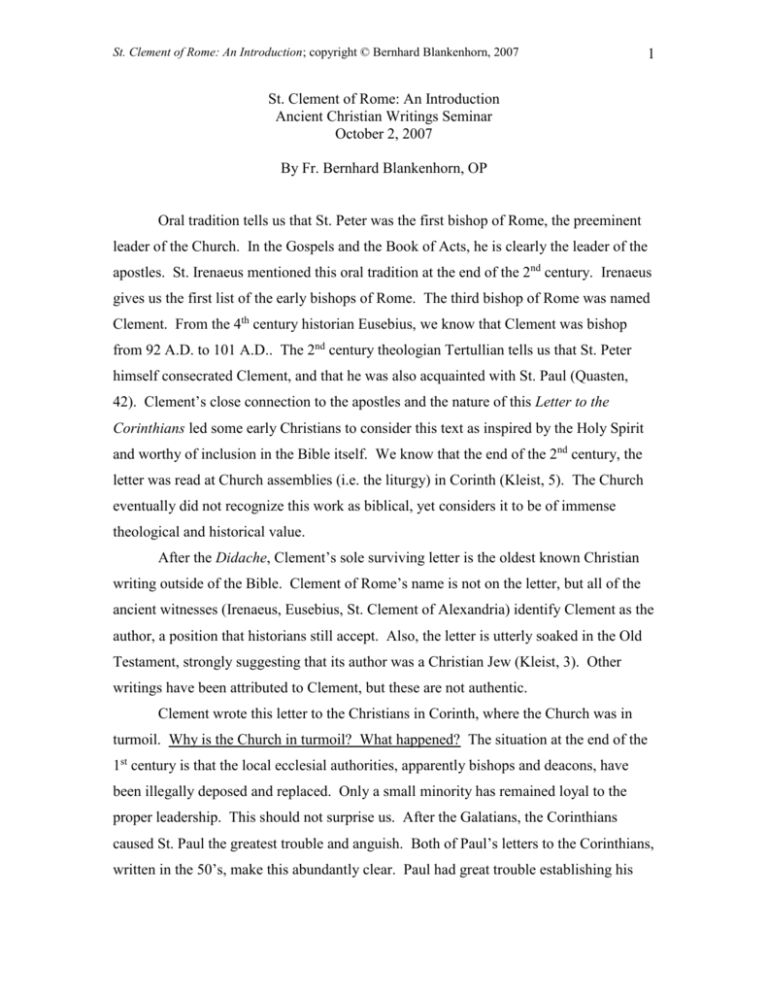

St. Clement of Rome: An Introduction; copyright © Bernhard Blankenhorn, 2007 1 St. Clement of Rome: An Introduction Ancient Christian Writings Seminar October 2, 2007 By Fr. Bernhard Blankenhorn, OP Oral tradition tells us that St. Peter was the first bishop of Rome, the preeminent leader of the Church. In the Gospels and the Book of Acts, he is clearly the leader of the apostles. St. Irenaeus mentioned this oral tradition at the end of the 2nd century. Irenaeus gives us the first list of the early bishops of Rome. The third bishop of Rome was named Clement. From the 4th century historian Eusebius, we know that Clement was bishop from 92 A.D. to 101 A.D.. The 2nd century theologian Tertullian tells us that St. Peter himself consecrated Clement, and that he was also acquainted with St. Paul (Quasten, 42). Clement’s close connection to the apostles and the nature of this Letter to the Corinthians led some early Christians to consider this text as inspired by the Holy Spirit and worthy of inclusion in the Bible itself. We know that the end of the 2nd century, the letter was read at Church assemblies (i.e. the liturgy) in Corinth (Kleist, 5). The Church eventually did not recognize this work as biblical, yet considers it to be of immense theological and historical value. After the Didache, Clement’s sole surviving letter is the oldest known Christian writing outside of the Bible. Clement of Rome’s name is not on the letter, but all of the ancient witnesses (Irenaeus, Eusebius, St. Clement of Alexandria) identify Clement as the author, a position that historians still accept. Also, the letter is utterly soaked in the Old Testament, strongly suggesting that its author was a Christian Jew (Kleist, 3). Other writings have been attributed to Clement, but these are not authentic. Clement wrote this letter to the Christians in Corinth, where the Church was in turmoil. Why is the Church in turmoil? What happened? The situation at the end of the 1st century is that the local ecclesial authorities, apparently bishops and deacons, have been illegally deposed and replaced. Only a small minority has remained loyal to the proper leadership. This should not surprise us. After the Galatians, the Corinthians caused St. Paul the greatest trouble and anguish. Both of Paul’s letters to the Corinthians, written in the 50’s, make this abundantly clear. Paul had great trouble establishing his St. Clement of Rome: An Introduction; copyright © Bernhard Blankenhorn, 2007 2 authority among the Corinthians, even though he founded the Church there. Numerous pseudo-apostles and strange preachers were competing with the Apostle to the Gentiles. After trouble broke out, Paul’s first representative (Timothy) was not well received, but Paul’s second ambassador (Titus) apparently succeeded in restoring some order and renewing the Corinthians’ acceptance of Paul’s authority. Clement’s letter reveals that the peace was short-lived. Reading the Text The letter begins by describing the Churches in Rome and Corinth as sojourning communities. What does this imply? The Christian’s true home is in heaven. But the reference is utterly communal. The Christian community belongs in heaven, is only on pilgrimage on earth. Heaven is a communal reality, not me enjoying God by myself. In 1:2, Clement mentions calamities. The setting is the 90’s A.D.. Those of you who studied the Book of Revelation with me last year probably remember what happened in the Roman Empire then which was of the utmost significance for Christians. What was the problem or calamity during these closing years of the first century? The emperor Domitian had instituted worship of himself. Every good citizen was expected to participate. Only the Jews were exempt. But the Christians have just been expelled from the synagogue. Life and livelihood were now much less secure. The name of the Corinthians’ Church has been greatly reviled. A rebellion has occurred within the Church. The early Christians throughout the Mediterranean formed a closely-nit network of communication. Letters were easily exchanged. Roman infrastructure was excellent, allowing for frequent travel. Many Christians outside of Corinth have heard of the turmoil there. Clement is probably also referring to the damaged reputation of Christians among non-believers. There is an important lesson for us here. When we encourage open dissent against the Church, we can truly damage her reputation and create obstacles to the conversion of non-Catholics. In 1:2, there is probably a note of irony. Clement asks: “Who that has sojourned among you did not approve your most virtuous and steadfast faith? … Who did not congratulate you on your perfect and sound knowledge?” Can you think of anyone who did not always approve? St. Paul clearly did not. For example, in 1 Corinthians he St. Clement of Rome: An Introduction; copyright © Bernhard Blankenhorn, 2007 3 criticizes them strongly for failing to celebrate the Eucharist properly. Also, some Corinthians apparently did not believe in the resurrection after our death. There may be a bit of sarcasm in Clement’s voice: you Corinthians think you’re so advanced in the Christian life, that you are so right, as you have always been! Clearly, no one has ever had to question the correctness of your thinking! However, Clement’s main aim is to offer sincere praise for their past conduct which has, for the most part, been exemplary, with notable exceptions. What virtues or merits does Clement emphasize? The themes of humility, peace and submission to proper authority dominate. Notice that in 2:2, he connects a greater outpouring of the Holy Spirit with such proper conduct. Here we have a hint of a healthy doctrine of merit. The proper use of one’s spiritual gifts leads to a greater spiritual reward. The tone shifts radically in 3:1. Clement quotes Deuteronomy 32:15. Did you look up the biblical passage? Who is speaking? Moses is offering his last prophetic words to Israel. He warns of future trouble. Jacob, another name for Israel, will grow fat. Moses predicts Israel’s future prosperity in the Promised Land. Wealth will lead Israel to forsake God. They will arouse God’s jealousy with foreigners. What might Moses be referring to? Most likely, he means the worship of foreign gods, which is almost always the source of Israel’s trouble and suffering in the Old Testament. Now consider how Clement applies this biblical passage in his letter. Who is Jacob or Israel? The Church is the new Israel, the new People of God. Clement hardly invented the idea, as we find it explicitly or implicitly throughout the Book of Revelation (1:7, 1:11, 1:20, a work written about the same time as Clement’s letter) as well as in the writings of St. Paul (who calls the Church “the Israel of God”) and St. Peter (1 Peter 2:910). The new Israel has become fat. This image was best explicated by one of the Dominican friars who preached a homily on it a few years ago. Remember that we are dealing with an age where few people ever had enough food. Hunger was an everyday reality for most ancient peoples, including the Jews. Moses instead paints an image of future prosperity that will bring certain spiritual pitfalls. Israel is like a little boy that is well fed, stuffed with bread at the table of God, the table of blessings. The little boy is utterly happy, kicking with joy. But such a state can lead to complacency and attachment St. Clement of Rome: An Introduction; copyright © Bernhard Blankenhorn, 2007 4 to the world. Historically, Israel often went astray in order to gain or retain temporal blessings, especially good harvests and political security. Chapter 4 focuses on jealousy as the root of many sins. I then skipped several chapters in the reading I gave you, though you have the link to study the entire letter. Chapters 5-6 show how jealousy led unbelievers to persecute Sts. Peter and Paul. Clement mentions their martyrdom, as well as the martyrdom of other Christians. Most likely, he means the persecutions under Nero in the 60’s, and perhaps martyrs in his own time in the 90’s. Chapter 7 calls the Christians back to the great rule of tradition that they have received, meaning the preaching and example of the apostles. Chapters 8-18 offer biblical examples of conversion and obedience to God, including Noah and Abraham. In chapters 20-21, Clement expounds upon the promise of divine peace that will follow proper submission to God. How is God’s peace manifested in creation? It is manifested by order. Clement seems to pick up on an idea that was current among the Stoic philosophers of his time. For the Stoics, the cosmos is divine and utterly ordered. By being in harmony with the order of the universe, we partake of God. Thus, to live in a moral way is to live according to nature, the order of nature (See Klest, 108). However, we need to remember that this Stoic idea of the order of the universe as divine had a striking parallel in ancient Hebrew thinking. Consider the creation account in Genesis 1. How does God create the world? By bringing order out of chaos, separating light from darkness, water from land, and so on. Here, the cosmos is not divine, but the order of the cosmos is made and willed by God. We find a similar idea in the latter chapters of the Book of Job, where God explains the mysteries of the universe that he orders and governs. Clement actually went well beyond Stoicism, which had no concepts of the cosmos as God’s creation or of God as a personal being (Klest, 108). In 21:4-6, Clement begins to set up a connection between proper conduct in the Church and the nature of the cosmos. What is this connection? The Church has its proper order and structure, like the cosmos. The order of the cosmos comes from and is sustained by God. The same is true for the Church. This becomes evident in chapter 40. What is the first explicit connection Clement makes between the order of the universe and the Church? It pertains to the proper celebration of the liturgy. But when did God give detailed instructions for sacrifices and services? What part of salvation history or St. Clement of Rome: An Introduction; copyright © Bernhard Blankenhorn, 2007 5 biblical history is he alluding to? He means the liturgical precepts in Exodus and Leviticus. This becomes clear in 40:5, where he refers to high priests, priests and Levites. Clement simply assumes that the Christian liturgy is a continuation of the Old Testament liturgy, which is highly significant. Chapter 41 emphasizes that the proper celebration of the liturgy is one that follows the very will of God. Chapter 42 shows how God’s will for the proper order of the Church was manifested. Jesus reveals God’s will, and the apostles pass on this message of Jesus. The apostles in turn appoint bishops and deacons. It is they who replace the priests of the Old Testament. The end of chapter 42 certainly implies this. What else does chapter 42 tell us? Jesus received authority from God the Father. Jesus in turn sent the apostles. They received “a charge.” The apostles in turn appointed bishops and deacons. The authority of bishops and deacons comes from God, who is the ultimate source of their “charge.” Chapter 43 continues the parallel between Old Testament priests and Christian bishops and deacons. Chapter 44 shows that the process of appointment is more complex than me might have thought. When apostles do not appoint bishops, the consent of the whole Church is sought for the choice of ministers. But Clement does not describe a purely democratic Church. The ministers are still approved by a higher authority (44:2). From the letters of St. Paul onward, we have explicit mention of the laying on of hands, which seemed to function as an ordination rite. An existing bishop thus had to consent to the appointment of a new bishop, since only an existing bishop could lay on hands. For example, in 1 Timothy 5:22, it is clear that Timothy’s consent is required for the choice of bishops in the communities to which Paul has sent him, not just the people’s. Chapter 47 shows the seriousness of the matter. The rebellion in Corinth is tearing apart the body of Christ. Apparently, only two persons are behind the whole turmoil. Clement speaks like a father with his children. Who else has learned of the division? Even unbelievers know of it, who now ridicule the name of Jesus because of it. Clement also implies Jesus’ divinity, since speaking ill of him is blasphemy. 59:1 shows why some considered this letter inspired and worthy of inclusion in the New Testament. Who is speaking through Clement? God himself speaks. Clement not only commands the rebel leaders to submit to the rightfully appointed presbyters, he St. Clement of Rome: An Introduction; copyright © Bernhard Blankenhorn, 2007 6 even claims divine authority. Earlier (in chapter 42), he suggested a theological foundation for this claim. Remember the chain of authority? Through Jesus and the apostles, the bishops have received authority from God himself. What is unusual is that Clement is not nor ever was the bishop of Corinth. Clement is the bishop of Rome. Who gave him authority over Corinth? Do we not see here an early manifestation of the primacy of Rome over other sees, one that the bishops of Rome would consistently claim in the early centuries and beyond? An appointee of St. Peter himself is making the claim. By the way, Clement’s command to submit to the presbyters is a direct quote from 1 Peter 5:5. Clement thus claims an authority similar to Peter’s. Remember that Clement is occupying Peter’s Episcopal chair in Rome. You may wonder where the presbyters came from, when Clement was dealing with bishops and deacons earlier. The word presbyters seems to be a synonym for bishops. We find this in Paul’s Letters to Titus and Timothy as well. We are at a stage where priests and bishops were not always clearly distinct offices. We will deal with the details of the development of Church offices next week, when we read St. Ignatius of Antioch. Chapter 60 takes us back to the theme of cosmic order. To follow one’s proper leaders and not usurpers or rebels is to be in harmony with God’s order. The Church is like a microcosm of the universe. God’s order for the universe brings peace and harmony. When we live in accordance with the God-given order of the Church, we also find peace and harmony. Chapter 61 again notes that the authority of ecclesial rulers comes from God. This is why rebellion against them is rebellion against God. But does Clement think that the people of God should endure anything whatsoever from these divinely appointed leaders? Notice that chapter 44 highlights the character of the deposed leaders. They ministered without blame, with humility and peace. Good reports about them have reached Clement. He is insisting on restoring the rule of virtuous bishops and deacons. Clement does not seem to argue for the absolute power of bishops and deacons. The problem is that they were improperly deposed. If in fact Clement can demand submission and the restoration of the old bishops and deacons, could he not also claim the authority to replace incompetent Church officials? The text is not explicit, yet Clement’s St. Clement of Rome: An Introduction; copyright © Bernhard Blankenhorn, 2007 7 claims of authority are considerable and leave the door open for such a possibility. In the coming centuries, councils of bishops would claim and exercise this very power of replacing sitting bishops. Chapter 63 again claims that the Holy Spirit has inspired this letter. Clement then mentions his ambassadors who have delivered the letter. Bibliography James A. Kleist, SJ, The Epistles of St. Clement and St. Ignatius of Antioch (New York: Newman Press, 1978). Johannes Quasten, Patrology, Vol. 1: The Beginnings of Patristic Literature (Westminster, Maryland: Newman Press, 1949). Copyright (c) Bernhard Blankenhorn, 2007