Why The Essay - with david jones

advertisement

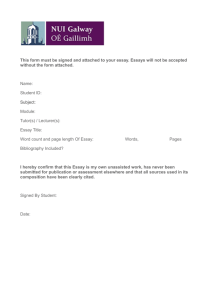

M.L.A Document Header

(For All Essays On This Course)

David Jones

Mr. Jones

Your Name

Your Instructor’s Name

Course Code

Date

Title

Jones 1

M.L.A.Page Header

(On Each Page)

ENG4U1*01

Thursday, August 17, 2006

Course Introduction: Why The Essay?

Welcome to ENG4U. We’ll be starting with “the essay” as our first topic as the

process of writing essays will help you develop the skill set at the core of this course.

The essay is also the assignment of choice in many university courses, a fact which might

lead you to ask “Why?” This is a good question, and one which might be best answered

initially at least, by defining the word “essay”, and then showing how the essay as

defined provides teachers with an opportunity to help students develop their ability to

think and write clearly. So what is an essay?

The word essay derives from the French essai

('attempt'), from the verb essayer, 'to try' or 'to attempt'. The

first author to describe his works as essays was the French

writer and thinker Michel de Montaigne (1533-1592).”

Montaigne’s essays were published in a work called

(no…honest!) “Essays;” a work which is described in the entry

on Montaigne at Wikipedia as “unprecedented in its candidness and personal flavor, he

takes mankind and especially himself as the object of study.”

(1)(http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Michel_de_Montaigne)

While Montaigne may have provided the original “essays” or attempts at

understanding a topic, the essay as a form has branched out into a variety of different but

Jones 2

related types of writing. The ways that essays are categorized and the number of

categories available really depends on who is setting up the categories. For instance, an

Internet Search on “Essay Types” will reveal a variety of University Writing Workshop

web pages, Internet “Paper Mills,” and other writing related web sites that provide

definitions for as few as three or four essay “types”—“classification,” “comparison and

contrast,” “cause and effect,” and “argumentative” essays for instance. (“Essay Types”)

But then there are sites that lump as many as 52 different types of writing into this

category. The winner in the “largest number of entries” category as I am writing this

paper for instance—the 52 entry site just mentioned—was found at “ The Paper

Experts”, an paper mill clearly trying to scare students out of writing essays and into

buying one. In this case it looks like the paper mill is trying to increase sales by

overwhelming potential essay writers with just the variety of essay types it is possible to

write (the implied message: ”there’s just so much out there that you’ll never get a grip on

essay writing; you may as well buy one instead.”). Whatever. At any rate The Paper

Experts, includes, in its list, everything from the “Analysis of a Book,” to “Timed,”

“Scholarship,” Deductive,” and Division and Classification” essays.(“List of Essay

Types”)

If there are so many different types of essay, do they have anything in common?

They do, and it is this common set of elements that makes the essay a useful form for

teaching those generic thinking and writing skills that will help students approach the

variety of topics or situations that they will, no doubt, be confronted with in their future.

One core characteristic common to all essays—one so fundamental that it is often

overlooked—is the fact that essays are about something: essays (except badly written

Jones 3

ones) are “focused” and address one idea at one time, an area of study, a “topic.” Even if

the topic is a complex one—even if the essay being written is long and multipartite—the

essay is about one “thing.” The process of dealing with that one topic often requires the

essay to be broken down into several sub-discussions, which may in turn be broken

down even further, but the fact remains that essays are “about something”: well written

essays at least, have one topic and stay focused on that topic.

The topics addressed in essays are as diverse as humanity itself; the essay as a

form has been used to address everything from the most universal human problems, to

very narrowly defined specialty topics; from ideas that are completely profound, to ideas

that are banal and frivolous: as a for instance one topic used as a first essay by one

university writing class had students describing their favourite flavour of ice cream and

why they liked it so much. I will let you decide whether this is banal or profound.

As a form the essay provides a fundamental organizing strategy for thinking about

things in an organized, structured manner: in order to write an essay about any topic the

extent of the discussion involved must be defined, and then broken down into some sort

of organized series of thoughts. Why break things down? Although we human beings

may be able to have many things going on in our minds at once—and there are many of

us that often have a lot racing around up there at any given time. I am not one of those: I

am one of those people known for being able to deal with, maybe, one thing at a

time…and often even that is a struggle. I am fortunate though, in that I have a partner

who often has, and can deal with her work, the laundry, what that funny noise is in the

refrigerator, and why I am not getting dinner together as I am supposed to be doing. At

any rate, although it is clearly possible to think about many things at a time, it is really

Jones 4

only possible to write about one. And it is best to stick to that one. And even if there are

several things a writer feels compelled to say about that topic, then it will be necessary to

organize that information in a meaningful way, and say those things one at a time.

All essays—well written ones at least—have a point or series of points that are

being made about one topic: a writer has considered a topic, has found a way to make

sense of this topic, and then explains his or her understanding of this topic one piece of

information at a time: this means that if, for instance, the essay being written is the

abovementioned “ice cream” masterpiece, the writer will have to do more than state that

“I like chocolate.” After all there must be a reason why that writer likes chocolate. And

while the process of explaining why she likes chocolate may be a simple little

comparative discussion of a preference of the richness of chocolate’s depth and bouquet

relative to strawberry’s saccharine goopiness, or as complex as a whole series of

Proustian rememberances, connections and their complex interconnections it is this

explanation that makes the essay an essay. Otherwise we just have a fact, and of course a

fact doesn’t really tell us that much, doesn’t reveal that much about the situation, the rich

complex human experience and history that underlies one’s preference for “Death by

Chocolate” as opposed to strawberry: a fact is just a fact—it’s not an essay.

Essays, because they require the writer to reflect on a specific body of

knowledge—ice cream, life and death, the use of imagery in Shakespeare’s Hamlet,

problems in the political economy of some new emerging state or [put your next essay

topic here]—require the essay writer to consider a body of knowledge; select facts, ideas

and other forms of data that will help that writer make sense of that body of knowledge;

oturn his or her understanding of this body of information into a coherent discussion and

Jones 5

then present this discussion in the most simple, direct, clear manner possible. The nice

thing about this core set of skills—examining and identifying information that is relevant

to a particular question or situation, selecting the information needed to address this

situation and any problems associated with it, organizing the information in order to

make sense of the topic, and then presenting an understanding in a manner that allows

someone to act—can be used and, in general, is used by effective thinkers who are

confronted with problems from shopping for groceries, trying to attract a significant

other, solving world issues, and/or trying to rule the world. As an example of how essay

skills are at the core of even the later

perhaps the most ambitious and complex of

these projects I would ask you, dear reader,

to consider the example of that most

ambitious pair of rodents—Pinky and The

Brain—who for a brief time, week after

week contemplated the task of taking over the world. Although Brain’s plans may have

been a little too ambitious, he was clearly organized, had a plan, a focus, and a clear

strategy that was easy to understand, and clearly communicated and unified. In this

respect Brain knew the basics behind how to put together a good essay. And if he had

considered his topic a little more closely—if, for instance he had thought about where his

plan might go wrong, if his analysis had been a little more thorough—Brain would, no

doubt, have succeeded eventually.

The understanding of anything we attempt in the world will only ever be as good

as our ability to organize, consider, communicate, and then act on our understanding of

Jones 6

this topic even if we are communicating this understanding to ourselves. And learning to

write an essay is learning to do the first three of these four things: learning to write an

essay is learning to develop those fundamental thinking skills that allows us to

address/consider whatever problems/tasks we have to face as post-high-school thinking

and acting human beings.

Something that allows us to see just how central the set of thinking skills included

in the process of writing an essay is to our post-high-school life, has to do with the way

that essays, when well written, can often very easily be morphed into some other practical

form that ends in a call for action, or organized plan to do something: essays can be

turned into reports, or included in reports, letters, memos and plans of action quite easily,

a process that you will get to see as we turn some of the essays we write throughout this

course into these other forms of writing

The course you are beginning to take is really mostly about the essay; it is about,

in this respect, learning how to think well. As a final word it is worth pointing out that,

given that the course is really about the essay, how to think and how to write, he most

important thing that you as a student can take away from this discussion and this course,

has nothing to do with your preference for ice cream, your understanding of Shakespeare,

or your desire to rule the world (that would be your own problem unfortunately): the

most important thing you can and should take away from this course has to do with your

ability to think about the next problem you are confronted with, the next situation you

must work out for yourself and others, the next topic you will be addressing; in its

essence learning how to write an essay is not learning how to solve the world’s problems

with Shakespeare, it is not learning how to psychoanalyze the deep inner desires you

Jones 7

might be manifest in your preference for chocolate ice cream—although both of these

look like interesting topics that some may think worth pursuing; learning how to write an

essay is nothing more nor less than just learning how to think. And if, at the end of this

course, you aren’t that much the wiser about William Shakespeare, and how he used the

pun in Hamlet that’s okay; but if by the end of the course you can think a little better, a

little more efficiently, a little more clearly, if you can do these things, well now, isn’t

that’s something.

Jones 8

List of Works Cited

“Essay Types.” Bogazici University Online Writing Workshop. 2006. August 18, 2006.

http://www.buowl.boun.edu.tr/essay%20types.htm.

“List of Essay Types.” The Essay Experts. 2006. August 18, 2006.

http://www.thepaperexperts.com/essays_types.shtml.

“Michel De Montaigne.” Wikipedia. 15 August 2006. August 18, 2006.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Michel_de_Montaigne.

Essay Analysis 1

Jones 9

Reviewing the Basics

Complete the following and submit as an attachment having, as file names, your last

name and initial (mine would be jonesd.doc, or jonesd.ppt (the PowerPoint) for

instance) to jonesjdavid@sympatico.ca Make sure that your submission is clearly

marked with your name, and includes all responses.

As an in-class exercise in preparation for the following we will develop a

synopsis of the essay provided above: to do so we will first determine what question or

questions this writer is trying to answer and then describe how he presents this argument.

Toward this end we will itemize the major points made in this piece of work, and then

what the writer argues in general. We will convert this material into a brief PowerPoint

presentation, and then use this material to demonstrate that essays are focused, and how

they maintain their focus—a process which will model the exercise to be completed

below.

In the following exercise you will once again be trying to establish, or at least

begin to explore how authors make a point, how they maintain focus, how they organize

their argument, how they use examples, and how these examples are explained.

1) You will work with a partner and read through one of the essays in the collection

provided for this exercise. Having read your essays you and your partner will

create a PowerPoint presentation in which you:

a. Identify what the essay is about (what the main topic of discussion

includes).

b. Describe an overall question that the writer of your essay was trying to

answer in writing the essays you have examined. Having established what

the major question being answered includes, you will then

c. Provide a bulleted synopsis of the major points made in this essay, and

what the author concludes in terms of an answer to this question, so that

you can then explain to the rest of the class how the essay you have

examined maintains its focus, and presents its argument.

Jones 10

the dismal science

Sinister and Rich

The evidence that lefties earn more.

By Joel Waldfogel

Posted Wednesday, Aug. 16, 2006, at 12:19 PM ET

It's well-known that many societies hold lefties in low esteem. In Christian tradition, the

devil is generally associated with the left hand; the word sinister comes from the Latin

for left, sinistra. Arabs have historically used the right hand for eating and the left for, er,

activities at the other end of the alimentary process. More scientifically, left-handedness

is related to a number of physiological conditions. Lefties have higher rates of high blood

pressure, irritable bowel syndrome, and schizophrenia.

On the other hand, if you'll forgive the inevitable bad pun, left-handedness is also linked

with creativity. Leonardo da Vinci was a lefty, as were Michelangelo, Isaac Newton, and

Albert Einstein. Psychologists confirm that left-handedness involves different brain

function: While right-handed people seem to have better cognitive skills on average,

studies find that lefties are more common among the highly talented.

What's the economic effect of left- and right-handedness—who makes more money,

lefties or normal people? Thanks to two new studies, one from the United States and

another from the United Kingdom, we have some answers. At least as far as earnings are

concerned, lefties have been unjustly slurred—if they're men.

There are two reasons to expect lefties to earn less, not more. About 11 percent of the

American population is left-handed (with slightly more men than women). Learning and

working in a world of machines designed for majority righties, lefties are at a

disadvantage. Tools like the screwdriver work well for both. But others, like the scissors

and the standard classroom writing desk and the electric food slicer and the band saw—

not to mention writing from left to right, with all the smudges and blackened fingers that

entails—are explicitly designed for righties. This ought to make lefties less productive.

(Hence the basis for Ned Flanders' Leftorium, the fictional store for left-handed people

on The Simpsons.) In addition, given the studies showing that lefties are more prone to

certain illnesses, they would be expected to be spend less time in productive activity and,

therefore, to earn less.

But that's not the case. In the new U.S. study, authors Christopher S. Ruebeck of

Lafayette College and Joseph E. Harrington and Robert Moffitt of Johns Hopkins

University looked at a representative sample of 5,000 men and women in the United

States. Across the board, they found no discernible difference between the average hourly

earnings, and other characteristics, of left- and right-handed people. Both groups earned

an average of $13.20 per hour in 1993. They also had identical average intelligence

scores. The British study, by Kevin Denny of University College Dublin and Vincent

O'Sullivan of the University of Warwick, looked at about 5,000 people born in 1958 and

found modest earnings differences: 5 percent higher pay for male lefties relative to their

Jones 11

right-handed counterparts and 5 percent lower pay for female lefties compared to female

righties.

What's more noteworthy is that the pay difference appears to increase with college

education. In the U.S. study, college graduates overall earned an average of 30 percent

more than high-school graduates. And after accounting for other determinants of pay—

age, intelligence, marital status, and race and ethnicity—lefties with college education

earned 10 to 15 percent more than their right-handed counterparts. (The U.K. study did

not look at the effect of college education on the earning power of lefties and righties.)

The identification of two styles of thinking may help explain why college-educated lefties

make more. Psychologist Stanley Coren defines "convergent" thinking as "a fairly

focused application of existing knowledge and rules to the task of isolating a single

correct answer." "Divergent" thinking, by contrast, "moves outward from conventional

knowledge into unexplored association." There may be an outsize number of lefty

geniuses because lefties are more likely to engage in divergent thinking. In an experiment

in which subjects devised uses for pairs of common objects, such as imagining that a

stick and a can could together be a birdhouse, lefties on average came up with nearly 30

percent more uses.

But the tendency toward greater aptitude in divergent thinking holds only for male lefties.

Psychologists don't know why this is the case. One hypothesis concerns differing levels

of fetal testosterone. This is just a possibility: Psychologists agree that the relationship

between left- and right-handedness and brain function is still not well-understood.

Whatever its cause, though, the male lefty advantage may have an economic effect: The

boost in earnings found in the U.S. study was associated with left-handedness only for

men. The study found no systematic difference between the pay of women lefties and

women righties, regardless of education or other factors.

These results suggest that education and an edge in divergent thinking are a potent mix

that put college-educated male lefties on top in the earnings game. Any practical

consequences? If your family's college fund runs short, you might send your lefty sons to

college and the rest of the brood to trade school. And if you're at a college mixer or

alumni reunion looking for a mate with high earning potential, you might keep an eye out

for the guy who wears his watch on his right wrist.

Joel Waldfogel is the Ehrenkranz family professor of business and public policy at the

Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania.

Article URL: http://www.slate.com/id/2147842/

Copyright 2006 Washingtonpost.Newsweek Interactive Co. LLC

Jones 12

family

Fear of the Deep End

What's the best way for kids to learn to swim?

By Emily Bazelon

Posted Thursday, Aug. 17, 2006, at 11:26 AM ET

"You'll only build a sand castle with me if I swim to the dock?" My 6-year-old son, Eli,

asked my husband, Paul, this question a couple of weeks ago as they stood on the shore

of a Maine lake. Eli didn't sound plaintive; he wanted to make certain that he had his

facts right. Paul replied in a deliberately even tone, "No, I'm going to swim to the dock

right now and I think it would be fun for you to come. But if you don't want to, I'll build a

sand castle with you when I get back."

If this sounds all too practiced, that's because Paul has been waging a campaign to get Eli

into the water for several summers now. My husband comes from a family of avid

swimmers who revel in jumping into lakes—the colder, the more memorable. When

Paul's father tossed him into freezing water in Nova Scotia as a kid, he howled in protest,

but nonetheless considers the episode a badge of honor—baptism by ice. Eli, however,

hasn't been a bearer of this family tradition. Much of the time, he is the sort of child who

loves to please, but persuading him to put his head under water took great effort, and he's

even been skittish about playing in shallow water in which he can easily stand. During

past summers, Eli has spent vacation weekends on the sand or at the side of the pool,

keeping all but an occasional toe dry, his refusals becoming louder and firmer the more

we tried to coax him. This has led to Paul asking me uncharacteristically surly questions

about why our kid is acting like a ninny.

The struggle to get Eli to swim has taught me how much easier it is to act and feel like a

good father or mother when your child easily follows your lead. When parents talk about

their babies who sleep through the night or kindergartners who read to themselves, a note

of inevitable pleasure creeps into their voices as they explain how the child's signature

achievement is the output of their inputs. We may pretend to humility ("I mean, not that I

realized what I was doing …"). But don't be fooled. When we're proud of our kids, we're

usually sure they have us to thank. The corollary of this smugness is that if a child is

generally adept at fulfilling expectations, we wonder what we've done wrong when he or

she fails to. Watching Eli in the water, I started thinking that Paul and I shouldn't be

trying to teach him to swim ourselves. In the end, I learned, we weren't wrong to try. We

were just trying too hard.

The American Red Cross has taken the lead on swimming instruction in this country for

nearly a century. The organization says that this is all because of one man, Commodore

Wilbert Longfellow, who saw the death toll from drowning as an impending national

tragedy and started a Red Cross lifesaving corps in 1914. During World War I, the Red

Cross taught soldiers to swim with full packs and in combat conditions. By the 1920s, the

organization had established two national institutes to train swimming instructors. The

Jones 13

initial emphasis was on lifesaving and elementary swimming. That led to the step-by-step

program familiar from camp and the YMCA.

When I was a kid, you moved from "Beginner" to "Advanced Beginner" to

"Intermediate" to the hallowed designation of "Swimmer." In 1992, the Red Cross got rid

of the names—it says the progression was hard for some kids and parents to remember—

and replaced them with numbers, from Level 1 to Level 6. Kids still get a card for

completing each level, and according to my 12- and 7-year-old nephews, Zachary and

Matthew, this remains a prime motivator. The program looks like what we've failed to

develop in so many other areas of education: a national set of standards. Almost 2 million

kids participated last year. The Red Cross would like to raise that number, especially in

minority communities: According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention,

black children drown at twice the rate of whites.

Since 1957, when the Red Cross kicked off the separate program "Teaching Johnny To

Swim," the organization has also urged parents to help their kids get used to the water.

For infants and toddlers, that involves classes that children attend with a parent (or

another adult) as well as an instructor. And the Red Cross urges the parents of older

children to spend time with their kids in the lake or the pool. The idea is that kids are

encouraged to learn to swim if they're around water often.

But when a child is ready for Level 1 instruction—depending on maturity, perhaps at age

5 or 6—the organization thinks that ideally instructors, not parents, should impart the

requisite skills. "When I taught swimming, the rule was that the parents stayed behind the

glass in the hallway," says Don Lauritzen, a Red Cross health and safety expert. "We

didn't want them creating a distraction and extra pressure by shouting out if they saw

their kid doing something incorrect."

I like to think that Paul and I would never be so unrestrained. But pushing Eli to do new

things in the water (Blow bubbles! Float!) was probably the psychological equivalent.

We'd have been better off putting him on his stomach in the bathtub, pouring water on his

head, and giving him more time to splash around there. I learned this from my sister-inlaw. Her three children have taken to swimming more easily than mine, and when I

watched their youngest, Elena, play in the tub as a baby last year, I understood why. The

Red Cross calls this "water adjustment." Elena, of course, just thinks it's fun.

What of Eli's swim to the dock on our Maine vacation? He decided to swim with Paul

that morning, but insisted on lying on top of a raft while he kicked himself across the

water. I demonstrated the kick for the breast stroke and expected him to try it; naturally,

that went nowhere. The breakthroughs began later that week: Eli swam to the dock on his

own when he got to know a bunch of kids around his age who were comfortable

swimming and wanted to go with them. A few days afterward, we hiked with his cousins

to a mountain swimming hole. The water was bragging-rights chilly: Paul leapt in. Eli

hesitated. But then Zachary and Matthew jumped. They climbed out and did it again, this

time from a higher rock. Eli watched them jump and whoop with Paul a few more times.

And then he jumped, too.

Jones 14

Emily Bazelon is a Slate senior editor.

Article URL: http://www.slate.com/id/2147913/

Copyright 2006 Washingtonpost.Newsweek Interactive Co. LLC

Jones 15

clothes sense

Belle Lettrism

Thoughts on words on clothes.

By Anne Hollander

Posted Thursday, Oct. 2, 1997, at 3:30 AM ET

The current show at the Metropolitan Museum's Costume Institute concentrates on 20thcentury garments bearing words, letters, and numbers in various ways. There are a few

word-bearing accessories from earlier days--garters, stockings, fans, and gloves, most

with political or erotic reference--but the clothes date mostly from the middle to the end

of this century. Nevertheless the show's punning title, "Wordrobe," appears on the wall

with the displaced "a" in flashing red neon above the first "o." Right away we're meant to

think of Hester Prynne's big scarlet A, imposed by the godly community, which she

defiantly embellished with gold thread. In so doing Hester was transgressing a second

time, because in the 17th century, in which the novel was set (and in the 19th, in which it

was written), wearing letters for decoration on everyday clothing was entirely

unacceptable.

It is still disturbing, or was until very recently. Why is that? Words, letters, and numbers

on garments seem riskier than kittens, clouds, and flowers on garments, just as those

seem less natural than stripes, plaids, or checks. But what, exactly, is profaned by putting

words on clothes? Is it the garment, the person, or the words? I believe it is the writing.

The written word was accumulating its own sacred aura even before Homer and the

Bible. Ever since priests, scholars, and poets used writing to record Scripture, prayer law,

and history both exalted and prosaic, reverence for canonical writings has lent an august

power to written words themselves. And with all the weight of such a past, a certain

dread can still attach to the sight of them being frivolously used.

In the middle of this century, turning words into fashion seemed like just such a use.

Some of the designs shown at the Met reflect a serious daring; they are examples not just

of amusing invention but also of rule-breaking. Turning the cutout letters of Emily Post's

Advice to Debutantes into a debutante's dress (designed by Evans and Wong, 1996), or

knitting the preamble to the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence into a

cashmere sweater (designed by Joseph Golden, 1997), or even just making a dress out of

random alphabet-lace (French, late 1920s)--all these are ways of flaunting modern

fashion's basic iconoclasm.

After the show, I looked around the museum to see if I could find any paintings

representing people with writing on their clothes. I found only Christ and the Virgin and

the occasional saint, clad in ceremonial garments edged with golden or pearl-sewn words

from liturgy or Scripture--but these were worn only in heaven. Earthly mortals didn't

seem to have the privilege. Words or letters or numbers on your clothes set you apart as

some sort of human object, sacred like St. Anthony or shameful like Hester Prynne or

maybe useful like a team member.

Jones 16

There is, in fact, an old football jersey in this show, with a big number on it. But it's

mainly there as a foil to an evening dress by Geoffrey Beene (1968) with a football

number in glittering beading. Beene has another beautiful, sleek black one with a

sequined traffic sign emblazoned across the chest, a big, shiny yellow triangle with

"yield" in black capitals (1967). Wonderful to look at--with the meaning not lost, just

transmuted, by the sequins.

More stirring is a sheer bodysuit designed by Jean Paul Gaultier in 1994 that transforms

the wearer into a living banknote, all gray-green engraved swirls and crosshatching, with

an occasional "100" at salient corners. This stretches the theme a little, since there are no

words and it isn't the reproduction of a real bill. But it works, like so much else in the

exhibition, to show how practical signs can become erotic adornments on the human

surface, depending on texture and placement. This skintight, transparent garment turns its

pattern into a tattoo, a practice alluded to by several other items here, including some

skin-colored Gaultier swim trunks that seem to cover the genitals with a tattoo saying

"Safe Sex Forever" (1997).

Monograms have a natural place in the "wordrobe," but they were not invented for

clothing. The rich and the noble used to put them on personal effects to imitate the

ancient royal habit of stamping (or embroidering or incising) the king's property with his

personal cipher. Artisans would discreetly stamp precious creations with their own

monograms in minidesigner-label mode, while giving elaborate prominence to the

client's. There are plenty of surviving cigar cases, purses, boxes, lockets, brooches,

penknives, and all kinds of tableware with small maker-monograms and large ownermonograms; and there are mountains of antique household linen with embroidered

domestic monograms.

But none of these is clothing. Putting monograms on display on garments is very recent. I

know my mother thought monogrammed blouses and bathrobes vulgar--but not

monogrammed bracelets or guest towels; from which I gather that vivid personal

monograms on clothes were new in the '30s. Once everybody got used to them in the next

generation, it was very easy to replace them with YSL and CK and the double Gs in the

following one. And those have acquired a lot more prestige than our own ever had.

Sultan Sáladin, the great 12th-century Muslim opponent of the Crusaders, had an ornate

monogram that Mary McFadden borrowed to adorn a dignified 1993 ensemble that is on

view in this show. Of course it can't be read by those familiar with only Greek and

Roman letters; nor can all the beautiful Chinese and Japanese characters in this

exhibition, similarly reduced to abstract motifs by our inability to recognize what they

say. (It does seem unfair to love them only for their looks, as if we despised their minds.)

Unlike Judaism and Christianity, Islam has used script for sumptuous decoration of all

kinds. But the Islamic artists, like those in China and Japan, didn't forget that the

immortal soul of the word is its sense; nor that clothing, since prehistory, has made sense

without words. Arabic words appear on beautiful textiles, but not on those worn as

clothing. Similarly, Japanese calligraphy has a great artistic tradition, no less great than

that of Japanese watercolor painting or Japanese costume, and beautifully brushed poems

Jones 17

may appear next to watercolor images similar to those that often appear on clothes. But

the words do not go on the garments.

It has taken modern Western fashion to make that happen. Brocade or chiffon dresses

covered in who-knows-what utterances in beautiful Chinese and Arabic script, or dresses

wittily made of paper printed with the New York Yellow Pages, all express a joyful relish

in the decay of the written word, a forthright pleasure in the way its meaning has been

draining away. Indeed, you could view this show as a carnivalesque celebration of our

growing tolerance for illiteracy.

At the end of the show is a cluster of popular sportswear with Tommy Hilfiger, Donna

Karan, Nautica, the Gap, and such names applied to it. These prove that Hester Prynne's

proud display of her A was prophetic. For with the proliferation of shifting public

signage, slogans, logos, and the lava flow of printout, the words on your clothes are now

what certify your physical existence. They put you in harmony with the rest of the

material world, as well as with the electronically written universe on the Internet. Words

are now rarely carved in stone; printed books are quickly pulped; but endless messages

flicker momentarily on screens or on this month's T-shirt. The exhibition tells us that as a

vessel of lasting sense or sacred truth, the written word may be losing ground, but that as

a source of inarticulate comfort, it has gained much.

Anne Hollander is a regular contributor to Slate.

Article URL: http://www.slate.com/id/3099/

Copyright 2006 Washingtonpost.Newsweek Interactive Co. LLC

Jones 18

fashion

Better Than a Park Bench

Street-fashion blogs keep tabs on the world's most stylish pedestrians.

By Justin Shubow

Posted Friday, July 21, 2006, at 2:08 PM ET

Fashionistas have long fetishized the street. Yves Saint-Laurent led the way in 1960 with

his scandalous Beat Collection, which paid tribute to the beatniks who moped around

Paris' Left Bank in motorcycle jackets, black leotards, and flats. Designers—who had

traditionally associated themselves with high culture and the beau monde—have ever

since been finding inspiration in the vulgar masses. A cynic might say that by co-opting

rather than creating trends, haute couture has been trying to defend its prestige and

authority in an increasingly anarchic fashion world, one in which the forces of ready-towear and cultural anti-elitism threaten to win the day.

Whatever the reason for fashion's obsession with the street, keeping an eye on it has

never been easy. Strolling around town is tough on the shoe leather, and only insiders

know just where to look. The print media, meanwhile, has been of little help. Fashion

editors are more likely to devote what pages they have to the fashion establishment

(which pays for advertising) than to nameless but chic pedestrians (who don't).

Until now, the best-known exception has been the Sunday New York Times, which for

more than 10 years has been running—at a small size, on lackluster newsprint in the Style

section—Bill Cunningham's candid shots of stylish New Yorkers. But an exciting new

development is making it easier than ever to follow the look of the man (and woman) on

the street. Made possible by faster Internet access and cheaper digital photography, streetfashion blogs have sprung up all over the world, and they are quickly proliferating.

The best of these sites capture the joys of people-watching and offer an experience that's

more like lounging on a park bench than flipping through a fashion magazine. For one

thing, the blogs aren't label-conscious: Few identify the brands worn, and not one

mentions the prices paid. Their subjects also tend to be dressed casually, with few

business suits or cocktail outfits in sight. Even better, many of the subjects are actually

smiling—quite a faux pas in the fashion world, which still demands the scornful, stricken

look that traces back to Lord Byron. But the sites do share at least one trait with fashion

glossies: Most feature photos of young hipsters taken by young hipsters, with few

ordinary Joes or dowdy seniors on display.

The photography in the blogs usually consists of straight-on, full-length portraits, but a

few include some candid photojournalism. Unlike New York magazine's misanthropic

"Look Book"—which uses low camera angles that, intentionally or not, make its subjects

look like snobs with upturned noses—the sites try to portray people in a flattering or at

least neutral light. Anti-elitist and upbeat in tone, they tend to inspire appreciation or

emulation rather than envy. Refreshingly, those that include comments from readers or

the editors usually avoid the cattiness found in celebrity fashion blogs like Go Fug

Yourself.

Jones 19

Each site has its own distinctive look and feel, as determined by the taste and skill of its

editors and photographers (usually one person holds both jobs). In some, such as London

Street Fashion, the subjects pose self-consciously, while in others, such as Stockholm's

STHLMstil, they stand naturally and without pretensions. StilinBerlin prefers ordinary

people in mundane garb, whereas Shanghai's Meet Cute concentrates on teenage b-boys

and flygirls. On the amateurishly homey side, there is Singapore's the Clothes Project,

which contrasts with the slick production of Tokyo Street Style. Emphasizing the

individual over his or her attire, Paris' Facehunter puts decadent scenesters on display,

and significantly it is the only one to sexualize its subjects, who sometimes pose

provocatively. As of yet, there are no street blogs from Italy, which is surprising given

that country's ties to the fashion world. It's not a shock, though, not to find any from Los

Angeles—after all, more attention is paid to public attire in pedestrian-friendly cities,

which offer the most opportunities to see and be seen.

Upon surveying the blogs, it's tempting to generalize about the state of fashion around the

world. At the very least, these sites demonstrate that the shoulder-bagged urban hipster

will fit in wherever he travels. And this photo suggests that the plague of "high idiocy" Tshirts, which sport ironically dumb slogans like "Your retarded," has spread as far as

Singapore. Likewise, someone looking for local trends might conclude that Stockholmers

are fond of cheery, almost primary colors, that Berliners prefer knee-length skirts and

sundresses to trousers, and that Muscovites love busy patterns. One must be careful not to

extrapolate too much, however. Not being documentarians or anthropologists, the editors

end up revealing their own taste more than that of their locales.

Some of the editors prove to be unusually adept at capturing a particular aesthetic. For

instance, Helsinki's Hel-Looks, whose subjects always appear strikingly in sharp focus

against a blurry background, has recently been concentrating on trends in platform boots,

horizontally striped stockings (sometimes mismatched), and the style known in Japan as

"elegant Gothic Lolita," which is a morbid take on Victorian doll dresses. Appropriately

enough, it has also been offering plentiful examples of the Scandinavian look of

combining highly disparate items that nonetheless work together.

But the standout street-fashion blog is far and away New York's the Sartorialist. Unlike

nearly all of the others, it concerns itself more with adult elegance than adolescent

faddishness, and its subjects range from elderly Harlem popinjays to chic ladies on

bicycles. Paying special attention to fine men's clothing, it shows how even a fat, bald

guy can look dashing when clad in an impeccable suit and tie.

Helmed by Scott Schuman, a former showroom owner who used to work for Valentino,

the Sartorialist has attracted a large and influential audience (averaging 7,000 visits per

day) that includes a number of industry insiders. The comments posted by Schuman and

his sophisticated readership can offer quite an education to the unschooled eye. It is

possible, for instance, to learn the pros and cons of "freelancing" socks as well as how to

spot Italians by the length of their neckties. The best remarks, which reveal how

clotheshorses obsessively and discerningly judge others, bring to mind the example of

Jones 20

Beau Brummell, the 19th-century dandy who famously used to lounge in front of the bow

window of a London gentlemen's club while criticizing the dress of passers-by.

Schuman's blog has now become so well-known that he was recently asked to cover

men's Fashion Week in Milan for Men.Style.Com, and Esquire will soon devote some

space each month to his work. In October he will receive an even greater honor: Saks

Fifth Avenue will be showcasing the Sartorialist's photos in its landmark display

windows.

It is, of course, no surprise that the fashion industry has already begun to use streetfashion blogs for its own commercial purposes—indeed, the Marxist social critic Walter

Benjamin once accused the flâneur of being a "spy for the capitalists, on assignment in

the realm of consumers." But ultimately these blogs should strengthen the leveling and

decentralizing forces that continue to dismantle the once dominant fashion pyramid. The

time is long past when a few couturiers could dictate international style from the heights

of Paris. Thanks to the growing popularity of this new medium, it seems likely that a

leaderless multitude will increasingly influence fashion from the ground—or rather,

pavement—up.

Justin Shubow is a student at Yale Law School.

Article URL: http://www.slate.com/id/2146220/

Copyright 2006 Washingtonpost.Newsweek Interactive Co. LLC

Jones 21

sports nut

Shrinks in the Dugout

Sports psychology is more popular than ever. But does it really work?

By Daniel Engber

Updated Friday, July 28, 2006, at 5:43 PM ET

Last weekend, it seemed like Alex Rodriguez had lost his mind. "He is spooked," wrote

ESPN.com's Buster Olney after a dreadful stretch in which A-Rod made five throwing

errors and went hitless in 10 straight at-bats. Rodriguez insisted that everything was fine:

"That's life, we're human beings," he said. "I wish we were perfect. But I feel very

comfortable and very confident." His daily affirmation seemed to do the trick. He had

two base hits on Monday, another two on Wednesday, and he's been flawless in the field

all week.

This wasn't the first time we'd heard therapy-speak from A-Rod. Last May, he declared

that professional psychology helped him overcome a tough first season in New York. "It's

helped in baseball, for one, in terms of my approach to everything," he said. While some

of A-Rod's therapy has focused on abandonment issues and childhood trauma, his

professional colleagues have grown increasingly enamored of sport-focused "mental

training" regimens that promise optimized performance and easier entry into a "flow

state." A psychological-skills coach will teach a slumping player to use mental imagery

to visualize success. Or he'll suggest various methods of arousal control, like affirmative

"self-talk" that can help him psych up for crucial situations, stuff like, "Stay on target!"

and, "I can do this!"

Can sports psychologists really help the best players in the game play even better?

Nobody really knows. Despite all the scientific-sounding rhetoric, applied sport

psychology remains a qualitative science—more of an art form than a rigorous clinical

practice. It's not clear if mental training improves performance on the field; what

evidence we do have relies more on personal anecdotes than hard data.

The fact that baseball shrinks can't back up their work with numbers is at odds with the

trend toward rational decision-making among baseball managers. Egghead GMs like

Billy Beane and Theo Epstein have revolutionized the sport by using objective measures

to build their teams. You might expect this new breed of executives to demand the same

rigor from their psychologists.

In fact, a mental-skills coach can build a baseball career from a few dramatic success

stories rather than worrying about consistent statistical results. Jack Llewellyn became a

famous baseball shrink by getting credit for turning around a young John Smoltz. The

pitcher started the 1991 season 2-11; after working with Llewellyn, he went 12-2. Since

then, Llewellyn has had steady employment with the Braves, and the team has made the

playoffs 14 straight times. Llewellyn has had success with other players, but he can't

prove that his interventions always work—some clients boost their stats, and others don't.

Besides, manager Bobby Cox and pitching coach Leo Mazzone were around for those

Jones 22

playoff appearances, too. Could Llewellyn simply have been at the right place at the right

time?

Prominent sports psychologists get praised for their successes and don't get grief for their

failures. Harvey Dorfman made his career by helping out the Oakland A's during their

1980s glory years. But Dorfman couldn't save the career of Rick Ankiel, the Cardinals

phenom who stopped throwing strikes after his rookie season. The self-trained hypnotist

Harvey Misel assembled a roster of 200 major-league clients thanks to his work with Hall

of Famer Rod Carew. But Misel couldn't do much for Jim Eisenreich: "He helped me

relax while I was sitting in a chair, but that has nothing to do with playing ball."

Misel has a simple explanation for these less-impressive case studies. "We're only as

good as the people we work with," he told the Los Angeles Times. "The talent has to be

there." Other sports psychologists chalk up failure to players who won't stick with the

program. It's a reasonable premise—you can't expect to see results if your client lacks

ability or motivation. But from a scientific perspective, it's a sham. If you just write off

negative results, how do you know your intervention does anything at all?

University researchers have made this point for years. Back in 1989, leading sports

psychologist Ronald Smith argued that his field had entered an "age of accountability," in

which objective measures of success should guide clinical practice. Seventeen years later,

little progress has been made. A few recent papers are typical of the current state of

research: Five college students improved their three-point shooting after hypnosis

training, four amateur golfers improved their chip shots with imagery practice, and a

couple of girls improved their soccer shooting with "self-talk." According to Robert

Weinberg, longtime editor of the Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, there are plenty of

studies showing some correlation between psychological interventions and improved

performance, but relatively few that demonstrate a convincing causal link.

Practicing mental trainers claim that it's almost impossible to measure success using onfield statistics. A batter could take four good swings, they argue, and still go 0 for 4. A

pitcher who lowers his ERA might have benefited from "mental reps," or he might have

fixed his delivery thanks to conventional coaching. Instead, they argue, success should be

measured by the players themselves. (The academics call this a "qualitative analysis.") If

John Smoltz says Llewellyn turned his career around, then Llewellyn turned his career

around. Why shouldn't we believe A-Rod when he says therapy helps him through his

slumps?

In fact, we have every reason to doubt the testimony of professional athletes. Baseball

players in particular are notorious for ascribing their success to inane rituals, astrological

signs, and other hokum. Wade Boggs used to eat chicken before every game. If Boggs

says that eating drumsticks helped him get hits, should we believe him, too?

The distinction between superstition and sport psychology turns out to be rather narrow.

Mental trainers push their clients to develop systematic "preperformance routines,"

including relaxation breaths, focusing exercises, and self-talk. But what's the difference

Jones 23

between a psychological routine and a mystical one? When Nomar Garciaparra refastens

his batting gloves between every pitch, is it a preperformance routine or a superstition?

What about when Dirk Nowitzki sings David Hasselhoff tunes before he shoots free

throws?

Sport psychologists would argue that Nowitzki and Garciaparra are using cognitive

strategies. Their rituals make them feel more comfortable, which in turn helps them

perform. But if it all comes down to feeling comfortable, then you'll get good results as

long as you think your ritual will work. It doesn't matter if you're using focused mental

imagery or humming "Do the Limbo Dance."

Given the power of the placebo effect, it's no surprise that mental trainers say their

interventions only work when a player "buys in" to what they're selling. Sport

psychologists can be effective in part because they put a scientific imprimatur on the

rituals they promote. A player might feel more comfortable if he thinks there's a scientific

basis for him to shout, "Stay on target!"

A sport psychologist would be worth a lot of money if he could give players a genuine

competitive advantage. Perhaps mental imagery and self-talk really do work better than

superstitious fiddling. It wouldn't be impossible to find out. Full-on experiments—with

players assigned to different treatment groups—would yield the best data, but even that

level of rigor isn't necessary. Mental trainers could learn a lot just by keeping careful logs

of all their cases, with statistical outcomes for each player.

No one asks the baseball shrinks for these data. If a player's happy, then his team is

happy, and everyone calls the intervention a success. Does A-Rod think his therapy

works? Sure. Right now, that's all we have to go on.

Daniel Engber is a regular contributor to Slate. He can be reached at

danengber@yahoo.com.

Article URL: http://www.slate.com/id/2146635/

Copyright 2006 Washingtonpost.Newsweek Interactive Co. LLC

Jones 24

sports nut

Tour de Farce

Floyd Landis' positive test shows why drug testing will never work.

By Brian Alexander

Posted Thursday, July 27, 2006, at 6:46 PM ET

Like much of the rest of the world, I was thrilled by Floyd Landis' startling comeback in

Stage 17 of the Tour de France. But since I write about doping and sports, I've learned to

be suspicious of miracles. The real tragedy of doping is the way it tarnishes everything

and everybody and forbids us from giving in to the wonder of sports. And now the news

comes out that Floyd Landis tested positive for high testosterone levels following that

very same miracle stage. There is a disheartening feeling of inevitability about the whole

thing.

It is certainly possible that Landis did nothing wrong. The test the Tour de France uses

for testosterone does not actually detect the use of a drug; it detects a ratio of testosterone

to another hormone called epitestosterone. There are vagaries, the science can be

imprecise, and it is known that massive athletic effort can fog the test. Innocent until

proven guilty and all that.

Regardless of Landis' fate, this episode, and the banning of a group of top riders before

this year's Tour began, illustrates why the current system of doping detection and

"justice" does not work. The main reason why it doesn't work is that the world, and

especially the American sports consuming public, is not ready to embrace the changes

necessary to leech drugs from sports. Sure, Congress holds hearings on steroid use in

baseball. Sports officials make earnest statements, and athletes decry those among them

who dope. Fans and editorial writers demand action. But do they realize what they are

asking for?

That the current testing regimen does not work to prevent doping is painfully obvious.

True enough, Landis' "A" sample—the first of two needed to confirm that he broke the

rules—turned up positive. So, you could argue that the testing worked in this case. But if

his testosterone was low, what does that mean about the value of the test? You might

point to Tyler Hamilton, who was caught using somebody else's blood to boost his own

endurance by a new test that detects foreign blood cells. He was banned for two years,

sure. But how long had he been using that technique before he was found out by a brand

new procedure? Cyclists are always figuring out new ways to dope, and the testers will

always be playing catch-up. For example, there is still no urine test for human growth

hormone, a commonly used performance booster. There's also no test for a new drug

called Increlex, which gives athletes more insulinlike growth factor 1—a protein that

does essentially the same thing as growth hormone.

If a test won't stop doping, what will? The biggest crackdowns of recent times have been

the result of law enforcement action, not testing. The BALCO case blew up because the

feds started investigating the BALCO lab and because a track coach, Trevor Graham,

Jones 25

blew the whistle by sending a syringe of a previously undetectable steroid to testing

authorities. The scandal that wiped out the cream of this year's Tour crop was the result

of an investigation by Spanish police. During the last Winter Olympics in Italy, the

Italian police raided the quarters of the Austrian ski team. Nobody tested positive in

either the Spanish or the Austrian scandals.

When cyclists and track athletes get caught doping these days, their punishment gets

meted out by the World Anti-Doping Agency. This odd parallel justice system is not fair

to athletes, science, and sports consumers. In order to stamp out doping, WADA must be

backed by real law enforcement.

Italy has already taken a step in that direction. Athletes there could face jail for "fraud"—

competing under false pretenses. The Italian government treats doping as a criminal

matter, not something to be dealt with from the cosseted confines of sports. Now, a doper

must weigh the potential for enormous wealth and prestige that a victory would bring

against the possibility of a temporary ban from competition for a first offense. In the

Italian model, he must also weigh a stint behind bars or a substantial financial penalty.

We are faced, then, with a proposal to criminalize sports doping. There would be raids by

the feds, trials, and law enforcement resources burned in the pursuit of multi-millionaire

druggies. I'm not so sure we have the stomach for this. Barry Bonds is still a hero in San

Francisco. There are no boycotts of Giants games. And remember that if Bonds goes

down, it will be for perjury or tax evasion—none of the athletes involved in the BALCO

case will ever see jail time for taking performance-enhancing drugs.

Major League Baseball insists that it is taking care of its own drug problems, and the

sports-consuming public seems content to believe it. Only aficionados can recall who was

banned from track and field because of the BALCO case. Lance Armstrong, who has

struggled through years of accusations but has never officially tested positive for

performance-enhancing drugs, remains an American icon. And if it would be hard to

muster support for a federal justice role here, think about the difficulty of mounting an

international effort. Just imagine the outcry the first time French police pick up a star

American tennis player during the French Open.

This is what American consumers have to ask themselves: If we really want doping to

stop, we have to be prepared to see our heroes do hard time. Do we care that much?

Brian Alexander writes about drugs and sports for Outside magazine.

Article URL: http://www.slate.com/id/2146630/

Copyright 2006 Washingtonpost.Newsweek Interactive Co. LLC

Jones 26

From: Seth Stevenson

Subject: Step 5: Actually Liking Stuff

Posted Friday, Oct. 1, 2004, at 2:27 PM ET

Click for today's slide show.

In the mid-1970s, famed author V.S. Naipaul (of Indian descent but raised in Trinidad)

came to India to survey the land and record his impressions. The result is a hilariously

grouchy book titled India: A Wounded Civilization. Really, he should have just titled it

India: Allow Me To Bitch at You for 161 Pages.

I hear you, V.S.—this place has its problems. As you point out, many of them result from

the ravages of colonialism … and some are just India's own damn fault. Still, I've found a

lot to love about this place. For instance:

1) I love cricket. The passion for cricket is infectious. When I first got here, the sport was

an utter mystery to me, but now I've hopped on the cricket bandwagon, big time. I've got

the rules down, I've become a discerning spectator, and I've settled on a favorite player

(spin bowler Harbhajan Singh, known as "The Turbanator"—because he wears a turban).

I've even eaten twice at Tendulkar's, a Mumbai restaurant owned by legendary cricketer

Sachin Tendulkar. Fun fact: Sachin Tendulkar's nicknames include "The Master Blaster"

(honoring his prowess as a batsman), "The Maestro of Mumbai" (he's a native), and "The

Little Champion" (he's wicked short). His restaurant here looks exactly like a reverseengineered Michael Jordan's Steak House. Instead of a glass case with autographed Air

Jordans, there is a glass case with an autographed cricket bat.

And in what could turn out to be a dangerous habit, I've begun going to Mumbai sports

bars to watch all-day cricket matches. These last like seven hours. That is a frightening

amount of beer and chicken wings.

2) I love the Indian head waggle. It's a fantastic bit of body language, and I'm trying to

add it to my repertoire. The head waggle says, in a uniquely unenthusiastic way, "OK,

that's fine." In terms of Western gestures, its meaning is somewhere between the nod

(though less affirmative) and the shrug (though not quite as neutral).

To perform the head waggle, keep your shoulders perfectly still, hold your face

completely expressionless, and tilt your head side-to-side, metronome style. Make it

smooth—like you're a bobble-head doll. It's not easy. Believe me, I've been practicing.

3) I love how Indians are unflappable. Nothing—I mean nothing—seems to faze them in

the least. If you live here, I suppose you've seen your fair share of

crazy/horrid/miraculous/incomprehensible/mind-blowing stuff, and it's impractical to get

too worked up over anything, good or bad.

(This is a trait I admire in the Dutch, as well. They don't blink when some college kid

tripping on mushrooms decides to leap naked into an Amsterdam canal. Likewise, were

there a dead, limbless child in the canal … an Indian person might not blink. Though he

might offer a head waggle.)

Jones 27

4) I love how they dote on children here. (I'm not talking about dead, limbless children

anymore, I'm being serious now.) At our beach resort in Goa, there were all these

bourgeois Indian folks down from Mumbai on vacation. These parents spoiled their

children rotten in a manner that was quite charming to see. In no other country have I

seen kids so obviously cherished, indulged, and loved. It's fantastic. Perhaps my favorite

thing on television (other than cricket matches) has been a quiz show called India's

Smartest Child, because I can tell the entire country derives great joy from putting these

terrifyingly erudite children on display.

5) I love that this is a billion-person democracy. That is insane. Somehow the Tibetan

Buddhists of Ladakh, the IT workers of Bangalore, the downtrodden poor of Bihar, and

the Bollywood stars of Mumbai all fit together under this single, ramshackle umbrella.

It's astonishing and commendable that anyone would even attempt to pull this off.

6) I love the chaos (when I don't hate it). Mumbai is a city of 18 million people—all of

whom appear to be on the same block of sidewalk as you. If you enjoy the stimulation

overload of a Manhattan or a Tokyo but prefer much less wealth and infrastructure …

this is your spot. (Our friend Rishi, who we've been traveling with, has a related but

slightly different take: "It's like New York, if everyone in New York was Indian! How

great is that!") And whatever else you may feel, Mumbai will force you to consider your

tiny place within humanity and the universe. That's healthy.

There's more good stuff I'm forgetting, but enough love for now. Let's not go overboard.

As they say in really lame travel writing: India is a land of contradictions. A lot of things

to like and a lot of things (perhaps two to three times as many things) to hate.

It's the spinach of travel destinations—you may not always (or ever) enjoy it, but it's

probably good for you. In the final reckoning, am I glad that I came here? Oh, absolutely.

It's been humbling. It's been edifying. It's been, on several occasions, quite wondrous. It's

even been fun, when it hasn't been miserable.

That said, am I ready to leave? Sweet mercy, yes.

Seth Stevenson is a frequent contributor to Slate.

Article URL: http://www.slate.com/id/2143259/

Jones 28

ad report card

SUVs for Hippies?

Hummer courts the tofu set.

By Seth Stevenson

Posted Monday, Aug. 14, 2006, at 11:43 AM ET

The Spot: A man waits in the checkout line at the supermarket. He's buying organic tofu

and leafy vegetables. Meanwhile, the guy in line behind him is stacking up huge racks of

meat and barbecue fixings. Tofu guy, looking a bit insecure, suddenly notices an ad for

the Hummer H3 SUV. Eureka! In a series of quick cuts, he exits the supermarket, goes to

the Hummer dealership, buys a new H3, and drives off—now happily munching on a

large carrot. "Restore the balance," reads the tag line. (To see the ad, click here, then

click "Enter Hummer.com," then click "Hummer World," then "TV Commercials," then

"Tofu.")

Each new generation of Hummer has been smaller and cheaper than the last. Remember

the original Hummer made available to consumers? Launched in 1992, during the height

of Gulf War patriotism, the $140,000, five-ton Hummer H1 was discontinued this June

because of poor sales. The absurd H1 begat, in 2002, the slightly less massive H2 (which

is still available). Last spring, Hummer scaled things down yet again, introducing the new

H3—a $30,000, relatively sanely sized SUV.

While the vehicles have grown less imposing over time, the brand's reputation hasn't

quite kept pace. According to Hummer spokeswoman Dayna Hart, there was a sense

among Hummer's marketing brain trust that the brand felt "expensive, too big, and out of

reach" for many consumers. What's more, recent Hummer ads have been a little lofty:

They've featured cool visuals of the trucks romping through dramatic landscapes but have

lacked everyday scenes of people enjoying their Hummers.

Enter this new H3 ad, which tries to make the brand feel a bit less intimidating. It shows

an ordinary dude (and not, say, Arnold Schwarzenegger) going to a Hummer dealership,

making a purchase, and driving out in a new truck. Which may seem basic, but showing

the transaction (and portraying it as lightning-quick and painless—the guy points at a

Hummer on the showroom floor, and a moment later he's the proud owner) helps make

the H3 seem more like a realistic option and less like a blingtastic pipe dream. And the

text that appears at the end of the ad touts the truck's 20-miles-per-gallon performance

and its $29,500 price tag, which further drags the brand back toward the sphere of

affordability and normalcy.

Hart says the spot aims to make the H3 a more "approachable vehicle that will appeal to

introverts, extroverts, vegans, and carnivores." She's right that we wouldn't expect a tofu

eater to buy a Hummer. But at the same time, the spot reinforces the central, classic

stereotype about Hummer drivers: They buy big cars because they have small … egos.

Jones 29

It's stunning how enthusiastically the ad embraces this idea. The entire plot is based on it:

A guy feels wimpy because another guy saw him buying tofu, so he dashes out and buys

a Hummer to feel better about himself. The original tag line of the ad was in fact "Restore

your manhood." Hart says people called in to complain ("The whole idea of manhood and

virility is a touchy subject," she points out, "especially for men"), so, after two weeks on

the air, the ad was recut with the line changed to the slightly more ambiguous "Restore

the balance."

Toned-down tag line or not, I can't believe this is an effective way to sell Hummers. I

imagine current Hummer owners are already tired of fending off accusations that their

vehicle is meant to make up for other shortcomings. Do they really want this notion

propagated by Hummer itself? Won't this ad sour them on the company and lead them to

buy a different truck next time? And what prospective buyer will be swayed by an ad that

explicitly suggests this truck's purpose is to compensate for inadequacies? How is that a

positive brand image? I thought the whole idea with Hummers is that their superior

capabilities (climbing steep inclines, muscling over tough roads) lend you street cred (or

off-street cred, I suppose) as the dude with the baddest beast in town. This ad has it

backward, eschewing all the performance hype and instead suggesting that the Hummer

is best employed as an image enhancer for wussy tofu hippies.

A second, similar spot—with a woman in the lead role—is no better. This time, the scene

is a playground, and the woman is standing alongside her son when another boy cuts

them in line for the slide. "I'm sorry, Jake was next," she says politely. "Yeah, well, we're

next now," replies the other kid's mom with a scowl. Once again, our wounded

protagonist races straight to a Hummer dealer and drives off with a truck seconds later.

The tag line this time: "Get your girl on." Interestingly, no one seems to have complained

about this take on femininity. But one of my readers suggests the message is this: "Even

women can have tiny dicks, and the Hummer is the cure."

Grade: C-. According to Hart, it was easy to swap out that "Restore your manhood" tag

line. Simply a matter of recutting the ad and then redistributing it to television stations.

Apparently, this sort of thing happens all the time—often in response to viewer

complaints—and is known as a "re-edit." So, if you see an ad that suddenly looks or

sounds different than you remembered it, you might not be imagining things.

Send your recollections of awkward or embarrassing "re-edits" to

adreportcard@slate.com. I'll try to confirm these with the advertisers, find out why the

edits were made, and get back to you down the line with a special "Re-edits Edition" of

Ad Report Card.

Seth Stevenson is a frequent contributor to Slate.

Article URL: http://www.slate.com/id/2147657/

Copyright 2006 Washingtonpost.Newsweek Interactive Co. LLC

Jones 30

technology

The Myth of the Living-Room PC

Why you don't have an Apple iTV.

By Paul Boutin

Posted Monday, Aug. 7, 2006, at 5:25 PM ET

Moments before Steve Jobs took the wraps off his supercharged new Macs in San

Francisco today, he took a minute to talk up the company's recent successes. As numbers

flashed on the big screen behind him, Jobs reviewed the latest stats on his retail stores.

But the one thing I wanted to see hard data on was conspicuously absent from Jobs'

keynote. It's been nearly a year since Apple added downloadable videos and a couchsurfing remote to its lineup. How are those doing, Steve? One more question: How come

none of my Apple-loving geek buddies have Macs in their living rooms?

It's not just Apple that's failed to invade the living room. Computer makers have been

trying to find space next to the couch for years, but so far all of these attacks have been

repulsed. In January, Intel launched a huge marketing program for an ambitious PCmeets-TV brand called Viiv. Instead of a keyboard and mouse, you'd control Viiv from

the sofa with a remote control. You'd download movies on demand, subscribe to TV

shows, search clips by keywords, and create a personalized, self-updating video

collection to watch whenever and wherever you want. This was the convergence of DVD,

iTunes, YouTube, and IMDb—couch potato heaven!

At the Consumer Electronics Show in Las Vegas, Bill Gates, Yahoo CEO Terry Semel,

and Tom Hanks took the stage to shill for these über-consoles, "available today starting

under $900." Viiv, promised the showmen, would download and play a mind-boggling

collection of video. I eagerly arranged for a loaner from Dell and typed up a gushing

preview for BusinessWeek. My Viiv never arrived. The few reviewers who got one were

stumped by the lack of new features on their test units. Seven months after Viiv's launch,

it seems what happened in Vegas stayed in Vegas: Dell's big rollout never happened, and

the rumor that Apple was launching a 50-inch plasma-screen Viiv turned out to be pure

baloney. This weekend, I found one lonely HP with a Viiv sticker at my local Best Buy.

The new HP flyer in my mailbox doesn't mention Viiv at all.

What happened here? Tech pundits say Intel botched their TV debut by pushing

technology that wasn't ready. Still, if the living-room PC is such a great idea, why hasn't

the Viiv void been filled with better alternatives?

My theory is that PC-TV hybrid products like Viiv aim for a sweet spot that doesn't exist.

Very savvy consumers will hack together these setups themselves. The less savvy will

just keep their TVs and computers separate. And the folks in the middle? If they're

around, nobody's found them yet.

If people actually wanted Viiv-like products, there'd be a lot more do-it-yourself versions

while we're waiting for Intel. If the problem were a lack of software, there'd be plenty of

Jones 31

open-source projects by impatient hackers—that's how we got Napster and BitTorrent.

But the geeks seem uninterested. Where are the obsessive bloggers? The forum feuds?

The amateur meetups? Show me any truly hot technology, and I'll show you 100,000

guys who can't wait to tell you about it. Has anyone bored you to death talking about

their Media Center PC lately?

You could argue that living-room PCs have simply yet to grow powerful and affordable

enough for the mass market. I asked Harry McCracken, the gadget hound who edits PC

World, what he thought of that notion. He dryly handed me a 1992 magazine whose

cover depicted Indiana Jones on a PC monitor. "Multimedia Magic with Full PC Power

TODAY!" the mag exulted. That could be a Viiv ad from seven months ago. We've had

the hardware to make some sort of PC-driven TV console for at least 20 years. With the

help of a simple adapter, you can see anything on your living-room screen that you can

see on your PC. Today's computers have the power for HD resolution, high-bandwidth

downloads, and house-wide networking. So, why hasn't the Great Convergence

happened?

McCracken says most homes are consolidating around a two-hub model. A PC (or Mac)

with some multimedia features anchors the home office, while a TV with some

computerized gear—think TiVo, not desktop computer—owns the living room. Tech

marketers talk about the "2-foot interface" of the PC versus the "10-foot interface" of the

TV. When you use a computer, you want to lean forward and engage with the thing,

typing and clicking and multitasking. When you watch Lost, you want to sit back and put

your feet up on the couch. My tech-savvy friends who can afford anything they want set

up a huge HDTV with TiVo, cable, and DVD players—then sit in front of it with a laptop

on their knees. They use Google and AIM while watching TV, but they keep their 2-foot

and 10-foot gadgets separate.

It makes sense that Apple pays lip service to convergence, but a dedicated product—even

a gorgeous, one-button iTV—would fall flat. In theory, TVs and PCs were supposed to

converge and spawn one hybrid media device. In practice, they touch on the couch

without breeding. TiVo buffs up your TV with PC-style software that ends the pain of

VCR programming. YouTube delivers a searchable trove of instant-play clips to your

computer screen. But when you plunk down on the couch to relax, you probably don't

want to search YouTube with a remote wand.

Computer companies should ignore what people claim they want and watch what they

actually do. We want the best of both worlds while still keeping them separate. I'm pretty

stoked about that buffed-up new Mac. It'll be a great way to watch movies … at my desk.

Paul Boutin is a Silicon Valley-based writer who also contributes to Business Week,

Wired, and Engadget.

Article URL: http://www.slate.com/id/2147258/

Copyright 2006 Washingtonpost.Newsweek Interactive Co. LLC

Jones 32

August 14, 2006

Ethicists say selling live lobsters is cruel. Are oysters next?

Could the Whole Foods lobsters-feel-pain ruling dampen our lust for oyster murder?

ANNE KINGSTON

It was in jest that Bertrand Russell uttered his famous quip about animal rights: "Where will

it end?" he asked. "Votes for oysters?" But, today, the British philosopher deserves points

for prescience: the latest frontier of ethical dining is aquatic, with talk of fish pain thresholds,

caught fish smothering to death, even oyster quality of life. Last month, Whole Foods threw

down the gauntlet on the "do-lobsters-feel-pain?" debate, announcing it would no longer sell

live lobsters because it could not guarantee humane treatment on their journey from sea to

table. The food blogosphere reacted quickly. "Where will it end?" one poster griped. "A

yogourt liberation league, protecting the rights of bacteria?" Chef and author Michael

Ruhlman vented on megnut. com: "No more salmon roe! Think of all those unborn salmon