episode2 - Planet Schule

advertisement

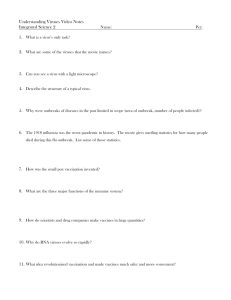

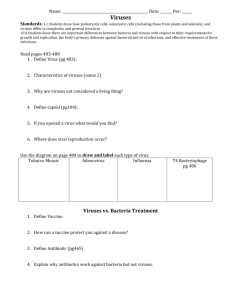

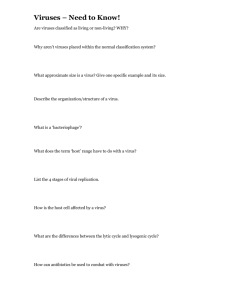

Speaker Script, Episode 2: Tricky Germs Distant places, foreign people, pictures that magically attract tourists. Travelers seek encounters with a world of exotic plants and animals, far removed from their daily lives. When adventure beckons, hardly anyone thinks of those invisible travelling companions - parasites, bacteria, and viruses. Pictures of these creatures do not look good on glossy tourism brochures. When the Ebola virus reemerged from the rainforest in 1995, the worlds was shocked. An epidemic had broken out in the town of Kikwit in Zaire, and even modern medicine stood by helplessly. The virus is transmitted through direct contact with infected persons, and even corpses must be disinfected. Ebola attacks the internal organs, leading to high fever and severe hemorrhaging. Of 300 patients, 244 died. Their deaths once again demonstrated that there are no vaccines at all for a whole range of infectious diseases. When the Ebola virus reemerged from the rainforest in 1995, the worlds was shocked. An epidemic had broken out in the town of Kikwit in Zaire, and even modern medicine stood by helplessly. The virus is transmitted through direct contact with infected persons, and even corpses must be disinfected. Ebola attacks the internal organs, leading to high fever and severe hemorrhaging. Of 300 patients, 244 died. Their deaths once again demonstrated that there are no vaccines at all for a whole range of infectious diseases. Villager: "One day two young men went hunting. When they returned to the village, they said they had killed a chimpanzee. The next morning, villagers set out to get the chimpanzee. They brought its meat back to the village and ate it. Within a week, they became ill. Some vomited, their noses bled, and they had severe diarrhea. My wife and entire family were struck by the disease that we are talking about." His daughter Vitali, five days before her death. Like her, thirteen of the nineteen infected villagers died within a short time. The trail of the virus led to chimpanzees. Researchers found traces of the Ebola virus in some of the dead animals. Now they just had to figure out how the apes had become infected. Chimpanzees prey on small animals and eat insects. It is suspected that the apes ingest the virus in their food and become sick. But this can be proven only if the virus is found in tissue samples from their prey. So far, the search has been fruitless. The host in which the virus survives, will for now remain a secret of the rainforest. Deadly viruses are popular mini-actors in movies. In Outbreak, the fantasy virus Mutaba is brought into the US along with a shipment of animals. Fate takes its course. Movie dialogue: 1: "Mutaba is transmitted only through direct contact with humans. These are your own words, Sam." 2: „I know what I said, but now we are faced with a new strain that spreads like the flu." 1: „So what's the problem?" 2: „Go to the hospital without a mask and see for yourself. Nineteen are already dead, hundreds are infected, and it spreads like bush fire. We must isolate the sick. I mean really isolate them, Billy. We must make sure that all others go home and just stay there." 1: „We are already doing that, Sam." 2: „o, we are not! I met hundreds of people on the way here, and if just one of them has the virus, ten others will catch it. And if one of them leaves Cedar Creek, we'll be in deep shit!" What's fiction and what's reality? How great is the danger that a pathogen will enter the country as a stowaway? Prof. Kurth: „The danger of a pathogen being brought into our country by tourists is no mere theory. We have experienced this internationally. These aren't any new germs, but ones that hide somewhere. They are almost always pathogens that reside in animals, and are not normally found in humans. But one can get infected and bring them along quickly when traveling by air. However, one should not sensationalize the danger, even though one often tends to connect the Ebola virus with Africa. If something like that is brought into our country, we have a whole series of measures ready to be undertaken to isolate and put the particular persons under close medical attention. Hence, I believe this potential risk is controllable in our country. Those affected though, could have serious health problems. There is no known vaccine against these pathogens, so no preventive action is possible." Hamburg, seat of the oldest tropical research institute in Germany. Established in 1893, it served primarily to treat sailors who had brought back infectious souvenirs from their voyages. Germany has a total of 16 institutes of tropical medicine. Their standard setup includes an isolation ward for suspected cases requiring notification of the authorities. The physician is not permitted to come in direct contact with the patient, which naturally complicates the examination. Any patient suspected of being infected with the Ebola or any other similarly nasty virus, would be kept in an isolation ward such as this one. The Hamburg Research Institute operates a laboratory with the highest safety level rating. Staff members are allowed to enter only with appropriate protective suits. Scientists here work with the most deadly pathogens in the world, named after the place where they were first encountered: Lassa, Marburg, Dengue, Krim-Congo, and Hanta. A considerable amount of effort is required to correctly identify a virus strain from among the multitude of different ones. There is no vaccine for most of them, and viruses have their own tricks to outwit the immune system. Animated film (Length: 2:17 min) Viruses try to escape from antibodies by seeking refuge in cells. Viruses are not self-reproducing. They thus force healthy cells to produce copies of the viruses, which then infect and destroy other cells. In order to contain a viral invasion, phagocytes and others move into action. They chop up the organisms into circular or square forms to make them recognizable. The circular ones are used as landing pads by T helper cells, the immune system managers. Activation commences following docking. The T killer cell has its own landing pad on the square shape. The killer cell is activated by a command from the helper cell. It divides itself and the hunt for virus-infected cells can begin. The infected cells also highlight parts of the pathogens. They are thus identified as targets for killer cells, and messenger chemicals trigger the cell's demise. The destruction of infected cells nips virus reproduction in the bud. Pathogenic agents are often very difficult to identify. Immunofluorescence has proven to be a helpful method. Specially prepared fluorescent antibodies attach to certain viruses or parasites. Their light trails unmask the pathogens. Slow-growth parasites are often not noticed until several weeks after a trip to the tropics. This type is diagnosed as Leishmania, caused by a monocellular organism transmitted through the bite of a sand fly. A visible sign is a deep wound on the back, caused by the body's futile defensive reaction. Leishmania has an especially devious survival strategy. The oblong parasite lets itself be captured and carried by a phagocyte as a stowaway into the body's interior. There it hides in a cavity, where it is able to reproduce undisturbed. Leishmaniosis is one of the seven common tropical diseases. Twelve million people are affected worldwide, among them an increasing number of tourists. Leishmania can attack not only the skin, but also inner organs. Treatment usually lasts several weeks. Patient: „I was in a Peruvian jungle in May and June, in a tropical forest, for about five weeks. There, we were bitten by all sorts of creatures. I think that's where this happened, from a mosquito." Simon Karalus's trip through the Manu National Park in Peru unexpectedly turned into a survival training adventure. Poorly prepared and with insufficient food and medicines, he lost his way and wandered aimlessly in the rainforest for weeks. Half starved, he finally found his way back. He had no idea that he might be one of the 400,000 people infected by Leishmania each year. Prof. Kurth: „On holiday trips, especially into the tropics, people are naturally at risk because they come in contact with a totally or largely different world of pathogenic agents. This may result in a harmless infection of the respiratory or gastrointestinal tract that then leads to Montezuma's Revenge, which ends up as diarrhea. Or there may be graver consequences if the pathogens are nastier, such as those transmitted through mosquitoes, of which there are plenty. With this degree of risk, the natives are not any yardstick for making comparisons, because they get infected in their own environment as youths. Whoever survives such an infection, becomes immune and will rarely get sick in adulthood. On the other hand, we are at a relatively high level of risk when traveling to these regions without such natural immunity." Anybody planning a trip abroad should consult his or her family doctor or a tropical research institute well in time. Depending on the disease, a vaccination may take one or two weeks to provide full protection. Many people forget this when they spontaneously decide on a last minute flight. Which vaccinations are necessary depends on the destination. In the case of Kenya, vaccination against yellow fever is strongly recommended. The virus is spread by mosquitoes and is life-threatening. This egg being injected with viruses is the first step in the manufacture of many vaccines. Viruses require living cells to reproduce, and chicken embryos have them in abundance. At the Robert Koch Institute in Berlin, the yellow fever vaccine is made with weakened viruses that have lost their disease-producing ability. The eggs are placed into the incubator for three days, where the viruses multiply at the ideal temperature of 38.5 degrees C. The viruses are subsequently collected, purified, and processes into vaccines. The compound is released only after successful tests. The idea of inducing immunity with weakened virus strains was practiced by the Frenchman Louis Pasteur. He initially achieved success with this method in the fight against fowl cholera. His spectacular breakthrough, however, was the discovery of a rabies vaccine. He took a sample of saliva containing the virus from an infected animal, and injected it into a rabbit's spinal cord. The virus reproduced there, becoming continuously weaker, and could then be used as a vaccine. Animals inoculated with it became immune. In 1885, Pasteur dared to test the vaccine on humans. A rabid dog had bitten a boy, who would certainly have died from this. Thanks to the vaccination, enough antibodies developed in time to successfully ward-off the slow growing virus. Rabies is still widespread. In Germany, foxes are the main carriers, followed by bats and rats. However, rabies has declined substantially in our latitudes since the administration of vaccine-filled baits. In contrast, there is still a high risk of infection, for example, in India or Thailand. There, a total of 40,000 people die annually due to rabies. Late in 1995. An invisible trio waited for its chance: A-Johannesburg, A-Singapore, and B-Peking. Humans made it easy for these influenza virus strains to conquer new ground. Germany alone had 20,000 fatalities. Shrugged-off as a harmless cold, a flu is often underestimated. Medical statistics show worldwide flu epidemics every two or three decades. In 1918, the Spanish flu killed 20 million people. This was twice the number that fell in World War I, which had just ended. In spite of modern vaccines, the risk of global epidemics has not yet been surmounted. Among the crowds in large cities, flu viruses find new victims effortlessly. The next host cell is never far away. Influenza viruses are true masters of camouflage, slipping unnoticed past the immune system guards. Animated film (length: 1:11 min) It is a well-known fact that viruses misuse cells as copying machines. The invading viruses are chopped down into their elements, duplicated, and reassembled. Sometimes, new variants develop as a result of copying errors. The immune system has not yet adjusted to these modified viruses and therefore cannot fight them effectively. The existing antibodies provide the best protection against the original viruses. They envelop and thereby prevent them from infecting other cells. However, if the new virus variants alter their surface significantly enough that antibodies can no longer attach to them, the viruses have succeeded with their camouflage. They have outwitted the immune system. Asia is the home of many kinds of influenza viruses. Transmitted from one person to another, they start their relay race to the West in the spring, arriving there in autumn. The latest virus strains that surface among humans in their homelands are registered by a global early warning system. This usually makes it possible to develop a vaccine in time. Nowhere in the world do animals and humans live so closely together as in Asia. This provides viruses excellent breeding grounds for developing new variants. Prof. Kurth: „Influenza viruses have the nasty property that their genetic material is available in fragments, which they are able to exchange with one another. This requires two viruses to enter one cell, which occurs in both the animal kingdom and among humans. Experience has shown pigs to be the melting pot for producing new strains, because pigs cab be infected in multiple ways - that is with their own flu viruses, with those from farmers, and also with those from poultry. The outcome of such a mixture becomes known only after it has formed. Hence, we have to repeatedly adapt ourselves to new epidemics at regular intervals. This genetic reassortment, as we call it, almost always occurs in pigs." A female anopheles having a bloody meal. This insect's eating habits make it one of the most dreaded among mosquitoes. It spreads malaria. A routine day at the Ifakara hospital in Tanzania. A child has been admitted. Diagnosis: Death from malaria. The mother is in despair. Each year, 200 to 500 million people are infected. For a million of them, especially small children, help comes too late. Malaria parasites proceed in an extremely ingenious way. They attack the liver as sporozoites. There, they change their identity and appearance. As merozoites, they enter red blood cells and reproduce themselves. This destroys the vital cells. Camouflage and deviousness are a part of the survival strategy of parasites. This makes it very difficult to combat them. Prof. Kurth: „The greatest problem when developing vaccines, especially against viruses and parasites, is that the pathogens like to change their covering, in other words their clothes. This is naturally a mechanism aimed at deceiving the immune system. Parasites usually have a very complex lifecycle. They take on various forms within the infected host. In malaria different kinds of cells are attacked one after the other. The immune system's response generally lags behind in such cases, because the pathogen can very quickly change its form again and again." The preventive medicines that tourists take are of little help to those living in areas where malaria is endemic. Taking medication for ones whole life would be neither reasonable nor affordable. As this farmer says, he does not even have the money for a mosquito net - the simplest and most effective protection against malaria mosquitoes. In Columbia, the biochemist Manuel Patarroyo has become a one-man advocate of the poor. He realized that only a vaccine could help the people in malaria-infested zones over the long term. He caused quite a stir in 1988, when he presented his anti-malarial vaccine SPF66 to an amazed public. This medicine consists of artificially replicated surficial components of various malarial parasites. He was able to demonstrate the effectiveness of the vaccine cocktail in animal tests. Could Patarroyo possibly have achieved the breakthrough that other researchers had sought in vain so far? Initial field tests in the Amazonian rainforest were encouraging. Fifteen thousand Colombians were vaccinated. Thirty percent of them developed immunity. The vaccine was, unfortunately, not quite perfect, but at least a good start. Patarroyo expected to be able to substantiate these initial findings with the SPF66 vaccine, in field-testing in Africa. However, things turned out differently in Tanzania and the Gambia. The new vaccine had no effect at all on small children, who suffer the most from malaria. As had so often occurred in the past, medicine lost out again to a dangerous parasite. Prof. Kurth: „We know, for instance, that elderly persons who live in malariainfested regions and have survived malaria, become immune after about two or three decades. So, resistance is possible. But we as scientists do not know how it works, what the immune system attacks, or against which antigens it acts. Trials conducted in the US and in South America over the last two or three decades, actually since the end of World War II, have not shed any light on the antigens such a vaccine needs to contain. Vaccination experiments or field tests conducted in Thailand, like prior ones from Africa, that have just been evaluated, have shown that experimental vaccines expected to generate a certain amount of immunity against malaria, simply do not work. So, we must start all over again." No great vaccine or medicine, however advanced it may be, can help relieve the most dreadful disease in the world: Extreme poverty! This is the number one killer. Malnutrition and poor hygiene weaken ones immune system. Under such circumstances, infectious agents have no trouble finding victims. And the number of the poor goes on increasing incessantly!