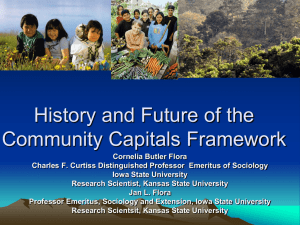

Annex 10: (Draft) final reports template

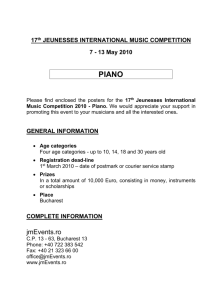

advertisement