I'm a teacher - The Good, the Bad and the Economist

advertisement

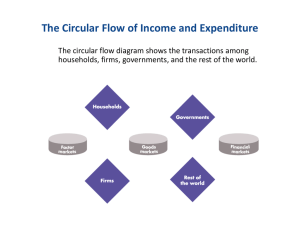

Chapter 36: Introduction to macro – economic activity and the circular flow model (2.1) Key concepts Intro to macro; main macro goals The circular flow of income model The identy of E = O = Y The circular flow of income model • Describe, using a diagram, the circular flow of income between households and firms in a closed economy with no government • Identify the four factors of production and their respective payments (rent, wages, interest and profit) and explain that these constitute the income flow in the model • Outline that the income flow is numerically equivalent to the expenditure flow and the value of output flow • Describe, using a diagram, the circular flow of income in an open economy with government and financial markets, referring to leakages/withdrawals (saving, taxes and import expenditure) and injections (investment, government expenditure and export revenue) • Explain how the size of the circular flow will change depending on the relative size of injections and leakages In this section we take a few steps back from the individual markets we have looked at so far in order to get an overview of all the different markets in an economy; goods, services, capital, exports, imports and labour. These are aggregates of individual markets and the relationships between them are, rather unsurprisingly, highly complex resulting in a great deal of disagreement amongst economic theoreticians as to how things actually work. There are, however, several points which economists are able to agree on with a minimum of bloodshed, namely that there are a number of overall macroeconomic goals. These goals can be encompassed in a ‘Four plus three’ list as follows: Intro to macro; main macro goals Growth – defined as the increase in gross national product (GDP) or gross national product/gross national income (GNP/GNI) and measured in money terms and adjusted for inflation Price stability – defined as a stable incremental increase in the price level (inflation) and measured by the consumer price index (CPI1) and the GDP deflator.2 Low levels of unemployment – defined as the number of people, out of the total available workforce, who do not have jobs and given as a percentage value External equilibrium – defined as stable exchange rates and balance between imports and exports (this is the focus of Section 4) In addition to the above four ‘mainstream’ goals, economists increasingly bring up issues to be found within the following captions: Environmental concerns – often defined as economic growth in compliance with ‘non-depleting’ and ‘non-degenerative’ resource use and measured using various environmental indicators of pollution over time Distribution of income – defined as how well income is spread between the richest and poorest sections of the population Productivity of factors – defined as the output per unit of input (factors of production) and often measured by labour productivity indices and capital use per money value of output All the above are subject to a variety of government policies aimed at achieving the goals or targets. The problem is that it is impossible to achieve all of the goals at once. In fact, virtually every macroeconomic goal will conflict with at least one other goal. A simple illustration is when an economy experiences increased output (goal 1 above) this often leads to inflation (making goal 2 more difficult) and possibly an environmental burden (conflicting with goal 5). As we shall see in Chapters 57 and 59, these conflicting goals will create numerous trade-offs for governments which in turn adds to an already heated theoretical and political debate. The circular flow of income model Let us expand the scale of our economy a bit and assume that it is comprised of households and firms – no financial institutions, government or other countries exist. The flows involved are shown in figure 3.1.1. Firms create the output (O) which is consumed by households – this is expenditure (E). (Note that since only a household sector exists, all expenditure (E) is in fact consumption expenditure (C).) Households are the actual owners of production factors and rent these out to firms for which an income is received (Y). (It 1The CPI is also known as the retail price index (RPI). are a number of other indices designed to calculate ‘underlying’ or ‘core’ inflation. More on this later. 2There is imperative that you view firms as separate entities which are owned by households! Ownership is either directly or via shares in the company. In other words, while the firm is responsible for producing goods and services, the buildings, machines and labour is supplied by households to firms for a price.) National income is thus a flow concept since we are measuring how much money is passing through the system during a given amount of time (normally one year) to handle all the economic transactions. In order to drive home the point that expenditure, income and output are indeed the same flows measured in different ways, I have compared the model to a closed-circuit heating system. (Yes, I know I’m being childish.) Picture a furnace in the basement of a house which heats water (illustration below) and forces a flow of hot water through a piping system and a heating radiator in a room above. The system is a closed circuit – no water can leak and no additional water can be injected. Therefore, no mater where one puts a ‘probe’ to measure the flow of water per unit of time the amount would be the same. Just think of a river which has narrow and wide sections; the same amount of water per minute flows by regardless of width – assuming that there are no tributaries (= inflowing streams) or seepage into the ground. Definition: National income National income is the real money value of the sum total of all final goods and services produced in an economy during a given time period – usually one year. This give the identity of expenditure ≡ output ≡ income, in money terms. As income is measured as an amount between periods, it is a flow concept. Figure 3.1.1 Circular flow in a simple economy Expenditure (E) on goods/services $ E (Radiator) Goods and services (O) Households Y Firms (Pipe) Land, labour and capital $ (Pipe) Y E Wages, rent, interest, profits (Y) (Furnace) Monetary flows Real flows The flows in the simple circular flow above match each other since we are making a number of assumptions in this simple model; there are no taxes, savings or imports so households cannot do anything but spend their income. Also, there are no exports, government spending or investment, which means that firms cannot sell their goods/services anywhere but to domestic households. This provides an uninterrupted flow since there are no financial leakages or injections into the system. The model also shows that there are two parallel flows in operation. One flow (inner black circular flow-arrows in figure 3.1.1 above) shows a real flow; land/labour/capital from households to firms corresponding to the output going from firms to households. The monetary flow (outer green circular flow-arrows) shows how households are rewarded with wages, rent, interest and profits (Y) from firms while firms are on the receiving end of households’ expenditure (E). (Type 3 Medium heading) Adding financial institutions, government and a foreign sector We now relax the above assumptions and include other parts of the economy making the model more realistic. Let’s follow the monetary flow of income through the system and see what happens. Starting at Y in figure 3.1.2, a household receives an income of, say, $100. The household will not spend all of this on output from domestic firms: A portion of the income flow will go to the government coffers as tax (T); Some will go to financial institutions (e.g. banks) as savings (S); And some of the remaining income will be spent on goods produced in other economies, i.e. expenditure on imports (M). Assuming that households pay $25 in tax, save $10 and use $15 on imports, then there are $50 left for domestic consumption (C). In other words, out of an income of $100 there has been a leakage (L) of $50 out of the system. Figure 3.1.2 Circular flow in a more complex economy Consumption expenditure (C) = $50 $ $ O=E=Y $ Output (O) = $100 $ Households $ Leakages (L) = $50 Taxes (T) = $25 Saving (S) = $10 T+S+M = G+I+X Firms Factors $ $ Income (Y) = $100 $ Injections (J) = $50 Govt. exp.(G) = $30 Government Fin. Inst’s Import exp.(M) Foreign = $15 sector Investment exp. (I) = $15 Export revenue (X) = $5 ∑L: ∑J: T S M G I X ∑L = ∑J But!: T≠G S≠I M≠X What happens to this 50? Simple, it flows in from other sectors in the model – these inflows are called injections (J). (Referring again to the radiator model, there has to be an inflow of 50 or the water pressure will not be enough to keep the flow up.) The taxes (T) will provide governments with funds needed for hospitals, defence etc, the public sector. This is government expenditure (G) which flows back into the system, i.e. to the firms providing these goods. Households’ savings will provide financial institutions with loanable funds which firms use for investment expenditure (I). And finally, there will be expenditure from the foreign sector which is an inflow of export expenditure (X) from abroad. To continue with the example of the ‘missing’ 50, posit that government spending is 30, investment is 15 and exports 5. This gives a total inflow of 50, i.e. total injections are equal to total leakages, since it is a definitional impossibility for more money to be pumped into the system than ultimately flows out. In the final calculation, the money value of injections must equal leakages. The money value of output must equal total expenditure – which in turn is the same as income. (Type 4 Smaller heading) Transfer payments You might have noticed that certain flows are missing in the circular flow model. Most governments have provisions to aid household incomes via some form of social welfare system, or social safety net: social security payments to low income households; housing allowances; student grants for university education etc. In addition to government transfers, certain economic transactions between households are missing in the circular flow model, such as payments for used goods and gifts of money. It is important to understand that all the above transfer payments are NOT included in the calculation of government spending in national income accounting. This money has already been accounted for in the national income accounts and does not represent additional expenditure, so adding it anew to the flow of G would be to double count it. The basic rule is that only the expenditure flows which have a corresponding output are included in national income. The identy of E = O = Y I usually introduce this keystone macroeconomic illustration by pulling a few coins out of my pocket (and as I never seem to have any money I mostly have to borrow them from one of my people) and ‘buying something’ off the table of a student; for example, a time management calendar (my people are scarily well-organised) for 100 Swedish Crowns (SEK). This simple transaction illustrates the entire macro model in one fell swoop; I have spent SEK 100 (= expenditure, E) on a good valued at SEK 100 (= output, O) and the student has received the SEK 100 as a payment for his/her output (= income, Y). Assuming a ‘two person economy’ as above, we see that total expenditure equals income (in money terms) which equals output. As a result of how we define expenditure, income and output in national income accounting, the three flows resulting from the simple economic transaction above are per definition identities, i.e. E ≡ O ≡ Y. We have now measured economic activity by assigning a monetary value to it, the SEK 100 paid for the calendar. On a wider scale, national income is simply the sum of all such transactions taking place during a given period of time. It is worthwhile to warn of a common error concerning injections and leakages. While it is quite apparent and perhaps even logically obvious that each leakage has a ‘mirror image’ or ‘counterpart’, this most assuredly does not mean that the values will be identical. The 25 money units of household taxes paid in the example above resulted in government spending of 30, i.e. G > T, an all too frequent occurrence unfortunately.3 This overspending is enabled by the government taking loans – which are provided by financial institutions… and these funds are supplied by depositors’ incomes…which are supplied by firms…and so on. Therefore taxes are not the same as government spending; savings do not necessarily equal investment; and imports are not equal to exports. It is instead the sum of these in- and outflows that must be the same. The circular flow model renders two sets of identities: 3This O = E = Y and J = L is the government budget deficit, and causes government to borrow – creating government debt. More later. A little depth: Algebraic method of proving that ΣJ = ΣL Regarding the flows on the left hand side in figure 3.1.2 (Circular flow in a more complex economy) it is clear that the income received by households goes to tax, saving, imports (consumption of non-domestic goods) and domestic consumption. Thus: Y=T+S+M+C Now look at the right side of the circular flow model. The very same firms which are paying for the use of households’ factors of production are on the receiving end themselves; consumption expenditure, government expenditure, investment expenditure, and export expenditure flow to the firms. We get: E=G+I+X+C And since Y = E, putting both sides together gives us: T + S + M+ C = G + I + X + C …and subtracting C on both sides gives us: T + S + M = G + I + X … which is nothing else than: ΣL = ΣJ. Summary and revision 1. The main macro goals are growth (increase in real GDP); price stability (measured by the consumer price index, CPI); low unemployment (defined as the percentage of the total labour force not holding a job); and external equilibrium (stable exchange rate and balance between exports and imports). 2. Other objectives include environmental concerns (e.g. sustainable development); distribution of income and factor productivity. 3. National income (here GDP) is the money value of all goods and services produced in an economy during a period of time – usually one year. 4. The circular flow model consists of households, firms, government, financial institutions and the foreign sector. 5. Injections in the circular flow model are government spending (G), investment (I) and export revenue (X). 6. Leakages are taxes (T), savings (S) and import expenditure (M). 7. The sum of leakages is equal to the sum of injections. 8. The three ways by which we measure national income are expenditure (E), output (O) and income (Y). These are an identity; E = O = Y.