gender and gender identity

advertisement

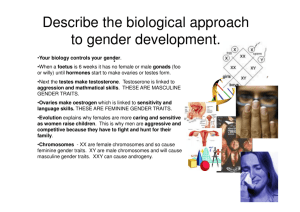

GENDER AND GENDER IDENTITY- BEYOND THE MALE/FEMALE DICHOTOMY Lorraine M. Fish Antioch University Seattle May 1993 In a world of dualistic black and white thinking, there is rarely any room for differences. Any contradictions of societal norms are branded as abnormalities, freaks of nature, and unfortunate individuals; all of which seem to constitute or represent a medical or psychological disorder. Though often perceived as a fixed dualistic phenomenon, gender has a vast grey area for attention and discovery. A much broader look at what constitutes gender or gender identity is an important ingredient for a richer and more expansive view and experience of human behavior. For a long time the psychological profession considered homosexuality as one such deviation that needed treatment. Impervious to drugs, brain surgery, and electric convulsive therapy, homosexuals have finally taken back their “psychological rights”. However, gender inconsistencies, both psychological and physical, have remained as “problems” that the medical and psychological professions seem compelled to “correct”; it has become important that we fit in with what is considered safe and agreeable. The American Psychiatric Association’s Desk Reference to the Diagnostic Criteria from DSM111-R is very clear and precise about what constitutes psychological disorders of gender identity, and lists the following Gender Identity Disorders: 302.60 Gender Identity Disorder of Childhood 302.50 Transsexualism 302.85 Gender Identity Disorders of Adolescence of Adulthood, Nontranssexual Type (GIDAANT) 302.85 Gender Identity Disorder Not Otherwise Specified (65-68) Of these “disorders” most include symptoms of: “Persistent discomfort and sense of inappropriateness about one’s assigned sex…For Females: persistent distress about being a girl, and a stated desire to be a boy (not merely a desire for any perceived cultural advantages from being a boy), or insistence that she is a boy. For Males: Persistent and intense distress about being a boy and intense desire to be a girl or, more rarely, insistence that he is a girl… Persistent and recurring cross dressing in the role of the other sex, either in fantasy or actuality, but not for the purpose of sexual excitement” (65-68). So it appears that unless one is clear about his or her gender, or is satisfied with the gender that is assigned, or even content with how gender identity should be expressed, there is room for society to be more than just concerned. Such concerns have, however, caused many individuals grief rather than solace. In a novel by Leslie Feinberg titled Stone Bitch Blues, the author chronicles the life of a woman who does not act or look like a woman. “Feinberg movingly portrays Jess’s rite of passage as she struggles to find a gender representation that will provide some safety in a world angered by her female maleness” (Nestle 29). This young woman struggling for a gender identity that fits goes part way through with a sex change but in a moment of illumination about what she is embarking on, ceases hormone treatments and puts an end to the process. “Her story thoroughly challenges our attachment to gender categories and becomes a voice for those who live with a more complex expression of gender” (29). Similarly, in a real life case story that makes the aforementioned novel consistent with reality, a Japanese man who felt like a woman trapped in a man’s body struggled with the same issues that Jess did. The man in question, Walter, went through intense turmoil around his gender identity, going from a period of cross-dressing, to wanting a sex change operation in order to experience life fully as a woman. His breast implants were inserted and removed many times, and to cease his gender confusion his doctor advised him to go ahead with the sex change operation. At that moment Walter wrote out a check for the operation, but tore it up later after having reconsidered. Though the operation was performed two years later, this did not end Walter’s gender conflict. Laura (Walter’s new name) finally stopped taking estrogen when s/he realized that life was not easy being a woman, and s/he wanted to revert to living as a man. It is clear that “Walter feels victimized by society’s expectation of what it means to be a man” (Monkerud 81-82). The debate over gender has certainly been around a long time and for the most part, centered on the nature-vs.-nurture controversy. Is gender an inherited biological given, or is it acquired through socialization of our culture? In the past few years reports abound with claims that science has found conclusive evidence that gender is a biological fact. “Ultimately, of course, our gender is laid down by our genes, which are bundled together in each cell in 23 pairs of microscopic packages called chromosomes” (Diamond 72). There is also the recent more controversial discovery that even homosexuality can be defined in biological terms. “Many researchers suspect that, in humans too, sexual preference is controlled by the hypothalamus” (Gorman 45). Such claims of course are, ultimately, riddled with many blind spots. In the case of gender being chromosomally defined, there are a variety of individuals who defy such absolutes. There are some people that have the male combination of XY chromosomes but have the ‘perfect’ body of a woman. The medical profession has defined these people as having a condition called Androgen Deficiency, who live their whole lives totally as women. In utero, it appears that there is a biochemical block in the ability to respond to testosterone. Therefore, without active testosterone in the body, the fetus will develop as a female. These ‘females’ tend to look ‘perfect’ but do not have some of the ‘correct’ female anatomy. Though many of these XY females do not know it, the testes that failed to work are hidden in the groin or labia, and there is no upper vagina or uterus. Hence these XY females do not menstruate. Such individuals have thus been labeled intersexual or pseudohemaphrodite, and are considered abnormal by the medical profession (Diamond 73). Through both biology’s and psychology’s concern with gender identity they have produced a multitude of theories. Among such theories about the development of gender there is a belief that: … children pass through a series of stages in acquiring a fully formed concept of gender. These stages include learning to identify one’s sex, understanding that gender is stable over time, and, finally, understanding that sex is a fixed and immutable characteristic that is not altered by situational changes (often called gender constancy). (Martin and Little 1427-8) This belief specifically contradicts instances where individuals who, though they appeared anatomically female as infants, begin to change gender during puberty and end up finally as males. This condition is somewhat similar to the previously mentioned Androgen Deficiency. In this instance, testosterone takes hold during puberty instead of in utero, and the clitoris grows into a penis and the testes emerge from inside the groin or labia (Diamond 71). In these cases gender is very definitely mutable. However, in Martin and Little’s article about understanding gender, they also make the point of saying that there is no resolution among theorists on the notion of gender constancy: The evidence concerning gender constancy has been mixed (see Carte, 1989; Stagnor & Rubble, 1987, for reviews). A few studies have found that attainment of gender constancy is related to children’s sex-typed preferences (Kuhn, Nash, & Brucken, 1978; Smetana & Letourneau, 1984), while others did not (Emmerich & Sheppard, 1984; Fagot, 1985; Marcus & Overton, 1978). (1428) There is so much about gender that defies the limits that either science or society sets. For the most part, there is a failure among most biologists, psychologists, and sociologists to recognize that gender is more than the culturally acceptable roles of male and female. One exception to this failure however, is the work of Eleanore Maccoby, a Stanford psychologist and pioneer in children’s research. “What research like Maccoby’s shows is that men and women do not have a set of fixed masculine and feminine traits; the qualities and behaviors expected of women and men may very, depending on the situation the person is in” (Tavris 292). Maccoby also determined that is was socialization that influenced a child’s gender identity much more than how male or female the child appeared (Monkerud 83). Correspondingly, in Martin and Little’s research on gender understanding they point out that “Constantinople (1979) and Fagot (1985) have argued that merely labeling the sexes is sufficient for children to begin to form rules concering gender” (1429). Hines, a UCLA behavioral scientist, who conducted a research project in the hope of resolving the issue of the origins of gender differences, videotaped children ages 2-1/2 to 8 years old at play. They were given boxes of toys that included many different sex-typed toys such as Barbie Dolls, kitchen toys, police cars, Lincoln Logs and fire trucks. Gorman’s report of Hines’ study states that: Although both sexes play with all the toys available in Hines’ laboratory, her work confirms what parents (and more than a few aunts, uncles and nursery school teachers) already know. As a group the boys favor sports cars, fire trucks and Lincoln Logs, while girls are drawn more often to dolls and kitchen toys. (42) Nevertheless, what such findings appear to confirm is that yes children learn very young from their family and culture about what is gender appropriate. Gorman goes on to state that among Hines’ subjects there was a group of girls that challenged her assumptions about gender and regularly chose the boy’s toys. Hines’ explanation for this phenomenon was that these girls had a “rare genetic abnormality that brought about extremely high levels of testosterone (and other hormones)” (42). It is common and easy to label that which is different as abnormal. Are gender anomalies abnormal? Or are they merely differences? There is the sense that differences are very scary for many people, that they perhaps challenge their own definitions of themselves. All that is ambiguous and obscure have become incongruous to much of the sciences and medical profession. In an article in a science magazine on gender anomalies, the writer states that “There are some unfortunate individuals called pseudohemaphrodites, who’s sex presents an ambiguous appearance…To find one’s gender ambiguous or shifting is as cruel a blow as could befall one’ ego” (Diamond 71-72). Whose ego, the doctor’s or the patient’s? In order to maintain a sense of security, it has become important that life be seen as black or white, either or, and measurable on some arbitrary scale. However, one person’s security blanket can be another’s nightmare: This becomes especially apparent in the case of an XX infant with normal female reproductive gonads and a perfect penis. Would the size and shape of the penis, in this case, be the deciding factor in assigning the infant ‘male,’ or would the perfect penis be surgically destroyed and female genitals created? Money notes that this dilemma would be complicated by the anticipate reactions of the parents to seeing ‘their apparent son lose his penis.’ …Elsewhere Money argues in favor of not neonatally amputating the penis of XX infants, since fetal masculinization of brain structures would predispose them to ‘almost invariable [to] develop behaviorally as tomboys, even when reared as girls.’ This reasoning implies, first, that tomboyish behavior in girls is bad and should be avoided; and second, that it is preferable to remove the internal female organs, implant prosthetic testes, and regulate the “boy’s” hormones for his entire life than to overlook or disregard the perfection of the penis. (Kessler 18-19) In order to have a broader perspective of gender I believe that it is essential to have a greater view of sexuality, for they are after all, intrinsically connected. It is often a matter of who is doing what, and with whom, that offends: During this century the medical community has completed what the legal world began - the complete erasure of any form of embodied sex that does not conform to a male-female, heterosexual pattern. Ironically, a more sophisticated knowledge of the complexity of sexual systems has led to the repression of such intricacy. (Fausto-Sterling 23) Given that there is a connection between gender identity and sexual identity, it would seem that the continuum that most experts agree exists within sexuality (Abner 61), should also exist with gender: “Kinsey and his co-workers also discovered a continuum of sexuality…Where sex is concerned, it turned out, you find all sorts of shades of “grey” (Fausto-Sterling 28). Abner, a writer for Essence magazine, talks about how sexuality is a fluid phenomenon and how scary “the fluidity of bisexuality” is for most people (61). Surely then this fear of differences has a lot to do with one’s own fear of how to assimilate the myriad of sexual nuances, subtleties and differences that exist in one’s own persona as well as in others, into a society that is not accepting of either gender or sexual diversity. While Freud was of the notion that humans are innately bisexual (“polymorphous perverse”), that they turn out to be either homosexual or heterosexuals a result of their early encounters with love and sensation (Toufexis 51), Jung on other hand believed that within each man there is a feminine psyche, the Anima, and within every woman there is a masculine psyche, the Animus. “Any consideration of the masculine and feminine patterns in the human psyche must include the concepts of animus and anima and a consideration of theoretical strengths and difficulties posed by these Jungian ideas” (Hill 175). Nevertheless, Gareth Hill further states that Jung’s concept is currently too rigid for a number of reasons; one being that in Jung’s era, gender roles were more clearly defined in a much more constricted manner than in the present day United States. “This made many of his applications of the concepts of animus and anima stereotyped, perhaps apt for his day and time and place, but now decidedly out of date” (175). In Hill’s book, Masculine and Feminine, he also points out that “We are caught in a bias that equates woman with feminine and man with masculine, confusing the archetypal patterns of masculine and feminine with corresponding social role characteristics of masculine and feminine” (178). In the athletic world, where the issue of gender specificity has become a grand arena for controversy, biases are plentiful. Everyone is concerned about fairness; females competing against males, or vice versa, is out of the question. Initially this process was intended to apprehend men trying to compete in women’s events. In order to eliminate gender impersonations, the Olympic officials have been scrupulous about testing females for biological gender since 1968. The medical test used to identify an individual’s gender is a simple procedure called a buccal smear in which cells are taken from the inside of the cheek and are examined for chromosome structure. It is based on the principal that males have an XY chromosome combination while females have the X X chromosome pattern. Since the onset of this procedure it has been widely discussed and disputed: But many doctors and scientists oppose testing, and Migeon’s story [about a top ranked runner who was urged to drop out of competitive sports because her physician, Migeon, knew she would not pass the chromosome tests] confirms their worst fears: first, that the tests unjustly disqualify women with unusual genetic conditions who are clearly female in body, mind, and athletic ability; and second, that testing, or even the mere threat of it, will filter down to younger and younger athletes and terminate their careers that have barely begun. (Grady 80) The athletic debate is just one example of how such narrow views of gender discriminate against individuals, and hurt people’s lives. Thank goodness we don’t bury people alive any more for gender transgression as was done during the latter part of the middle ages (Fausto-Sterling 23)! However, there are various gender transgressions being committed by the medical profession, auspiciously, under the guise of humanitarianism. “Scientific dogma has held fast to the assumption that without medical care [gender reconstruction] hermaphrodites are doomed to a life of misery. Yet there is few empirical studies to back up that assumption, and some of the same research gathered to build a case for medical treatment contradicts it” (Fausto-Sterling). Many hermaphrodites, pseudohermaphrodites, or intersexuals can and do live normal healthy lives. In fact, many of these people find mates and marry. Though those who are without a uterus or a functioning penis cannot bear their own children, they often adopt. However, there appears to be no evidence for any undue emotional distress (Diamond 74). It is estimated that thousands of babies are born each year in the U.S. (Diamond 72) that embody more than a dozen varieties of intersexuality in which there is a combination of the male and female characteristics (Grady 80). In many of these cases however, a decision is now made as soon after birth as possible about what gender the infant should be raised as; surgical reconstruction is performed to complete what the medical profession believes nature was unable to do. Nevertheless, much of the decision-making process about gender reconstruction is morally questionable because of prevailing cultural gender bias that exists among the predominantly male medical professionals: In fact, doctors make decisions about gender on the shared cultural values that are unstated, perhaps even unconscious, and therefore are considered objective rather than subjective. Money [John Money] states the fundamental rule for gender assignment: ‘never assign a baby to be reared, and to surgical and hormonal therapy, s a boy, unless the phallic structure, hypospadic or otherwise, is neonatally of at least the same caliber as that of same-aged males with small-average penises. (Kessler 18) It is therefore standard procedure for medical teams to depend on cultural agreements of gender as guidelines for decisions concerning the re-construction of gender. “Physicians hold onto the incorrigible belief in and insistence upon female and male as the only ‘natural’ options” (Kessler 4). In addition to such an insistence, Kessler states that there also exists a bias in favor of a particular gender and Kessler points to this by saying: The mere fact that this doctor refers to the genitals as an ‘underdeveloped’ phallus rather than an overdeveloped clitoris suggests that the infant has been judged to be, at least provisionally, a male…their words do reveal that they have certain assumptions about gender and that they impose those assumptions via their medical decisions on the patients they treat. (4-13) Yet there are a growing number of professionals who refute the notion that female and male are all that is biologically correct. “Western culture is deeply committed to the idea that there are only two sexes. Even language refuses other possibilities …” (Fausto-Sterling 20). FaustoSterling goes on to say that if our culture and legal system has “an interest in maintaining a twoparty sexual system, they are in defiance of nature. For biologically speaking, there are many gradations running from female to male. (21)” Sterling also suggests that the medical profession is determined to maintain the status quo and to “correct” any deviation, and in doing so, it continues to assist in the perpetuation of gender myths. “We perceive the world from a gendered subject position and we recreate the sexist world by recreating the male/female dualism in the things we do and say” (Davies 503). Fausto-Sterling’s article in The Sciences argues in favor of expanding the understanding of gender and she has delineated three major additional sex types, to be considered in their own right. These are “merms”, who have testes and some aspect of the female genitalia but no ovaries; “ferms” who have ovaries and some aspect of the male genitalia but lack testes; and “herms” (hermaphrodites), who posses one testis and one ovary. She says her proposed five sexes are still somewhat limiting, considering “that sex is a vast malleable continuum” (21). Ms. Tarvis’ book, The Mismeasure of Woman, also exemplifies the idea that male and female gender titles have excluded a vast ocean of differences. Tarvis states that: …there is a greater variation within each sex than between them. As one psychologist who reviewed these studies summarized: ‘The observed differences are very small, the overlap [between men and women] large, and abundant biological theories are supported with very slender or no evidence. (52) Likewise, Christine Gorman states in her Time magazine article that “Most of the gender differences that have been uncovered so far are, statistically speaking, quite small” (44). Tarvis’ view, however, is that women and men are neither opposite each other, the same as each other, nor inferior to each other, and she says of current gender distinctions: The result of this process [the culture gap that develops between men and women] is that gender, like culture, organizes for its members different influence strategies, ways of communicating, nonverbal languages, and the ways of perceiving the world. Just as in Rome most people do as Romans do, the behavior of women and men depends as much on the gender they are interacting with than on anything intrinsic about the gender they are. (291) The twentieth century, however, has become an era where gender distinctions are perhaps less obvious, where there is a trend towards a more androgynous expression of gender: “On the streets gender bending expresses itself in fashion. Men and boys are wearing earrings and hair of any length; women don boxer short…Many of our cultural icons, in fashioning their personas, play the gender game [David Bowie, Michael Jackson, Boy George and Grace Jones]” (Mokerund 82-83). Androgyny is one of those ways of being that exists in the scary domain of what we call the grey areas. Sandra Bem, a Cornell University psychologist, has illuminated this seemingly unmarked territory through her research of various possibilities for conceiving androgynous environments. In fact, she strived to raise her own children in such a genderless atmosphere. In his Omni magazine article, Monkerund quotes her as saying “For many people confused about how to behave as a man or a woman, androgyny provides both a vision of Utopia and a model of mental health” (Bem qtd. in Mokerund 83). Similarly, Thornton and Leo’s study about gender typing and its effect on the mental health of women, they concur with Bem’s statements, by adding that “Androgyny, on the other hand, is rather consistently associated with lower level of depression (Steenberger & Greenberg, 1990)…[and] [t]he relatively minimal substance abuse consistently displayed by androgynous women has suggested that the absence of gender typing itself may contribute to their decreased risk-related behavior (Wilsnack, Klassen, & Wright, 1985) (308). Nancy Chodrow, a professor of sociology at Berkeley, is quoted in an Omni magazine article by Don Monkerund as saying, “…and I make the case for gender as constructed culturally, socially, economically and politically” therefore, “Gender then may be in the eye of the beholder” (82). Certainly, it is obvious that for some that there are a multitude of advantages in the dichotomizing and construction of gender through the male and female roles. If there are only two genders then it is much easier for one to dominate the other! Clearly all theories are incomplete, but the vast grey area that science prefers to ignore or label abnormal does for the most part go unexplored (Fausto-Sterling 21). In reaching the position of viewing gender with a wide angle lens, one has to consider this point: “Classifying oneself and others, and being classified, are interesting and dangerous processes, because classification can be a way of controlling, of reducing . . . (Davies 502).” Perhaps, if our society can wean itself off the incessant need for classifications and polarized categories, we can live expansive, richer, and more peaceful lives. Works Cited Abner, Allison. “Bisexuality Out of the Closet.” Essence Oct. 1992: 61-62. American Psychiatric Association’s Desk Reference to the Diagnostic Criteria from DSM-111-R 1989: 65-68. Davies, Bronwyn. “The Problem of Desire.” Social Problems 37 (1990): 501-15. Diamond, Jared. “Turning a Man.” Discover June 1992: 71-72. Fausto-Sterling, Anne. “The Five Sexes.” The Sciences Mar./Apr. 1993: 20-24. Grady, Denise. “Olympic Officials Struggle to Define What Should be Obvious: Just Who is a Female Athlete.” Discover June 1992: 79-82. Gorman, Christine. “Sizing up the Sexes.” Time 20 Jan. 1992: 45-51. Hill, Gareth S. Masculine and Feminine. Boston: Shambala, 1992. Kessler, Suzanne. “The Medical Construction of Gender: Case Management of Intersexed Infants.” Signs 16 (1990):3-26. Martin, Carol Lynn and Jane K. Little. “The Relation of Gender Understanding to Children’s sex-typed Preferences and Gender Stereotypes.” Child Development 61 (1990): 1427-39. Monkerund, Don. “Blurring the Lines: Androgyny on Trial.” Omni Oct. 1990: 81-88. Nestle, Joan. “Shades of Gender, Shades of Hope.” New Directions For Women May-June 1993, 22:29. Rubenstein, Carin. “The Michael Jackson Syndrome.” Discover Sept. 1984:69-70. Tarvis, Carol. The Mismeasure of Women. New York: Simon, 1992. Thornton, Bill and Rachel Leo. “Gender Typing, Importance of Multiple Roles, and Mental Health Consequences for Women.” Sex Roles: A Journal of Research 27(1992):307-17. Touflexis, Anastasia. “Bisexuality What is it?” Time 17 Aug. 1992: 49-51.