BCRC Hazard Mitigation Plan - Bennington County Regional

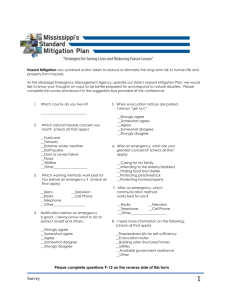

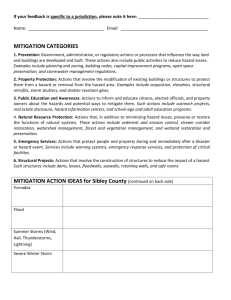

advertisement