11 - Ancient America Foundation

advertisement

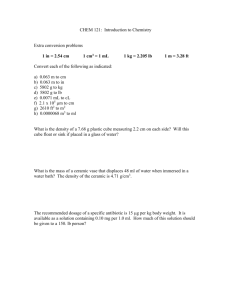

11.3 Northern Central American Ceramic Units and the Land of Nephi by Bruce W. Warren Introduction Recently, several Book of Mormon scholars have published some of their research on the geography of the Book of Mormon. These works have all placed the Land of Nephi in highland Guatemala (Palmer 1981:176; Sorenson 1985:1214,141-48,229-30; Hauck 1988:9,143; and Allen 1989:359-70). A couple of recent research concepts have been developed for using ceramics more effectively in historical and cultural reconstructions of the past. These two concepts are in the literature as "utilitarian ceramic tradition" (Hatch 1988:151-70) and "ceramic spheres" (Willey, Culbert, and Adams 1967:289315). A "utilitarian ceramic tradition" refers to locally made domestic ceramics that involves the same clay deposits and craftspersons using the same techniques of manufacture over long periods of time, i.e., several generations. The "ceramic sphere" concept refers to fine ware or nondomestic ceramics of the same cultural style that have spread over a large territory implying economic and political influence from a common center(s). I will deal with five "utilitarian ceramic traditions" and one "ceramic sphere" dating to the Late Preclassic and Protoclassic periods of the highlands of Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras. The timespan involved is from about 250 B.C. to A.D. 250. The geographical clustering of these ceramic traditions and the one ceramic sphere should have an important role in defining the location of the land of Nephi and other areas that the people in the land of Nephi were interacting with economically and politically. Unfortunately, the archaeological literature for Mesoamerica is full of chronological charts that use variant terminology. Table I will give my version of labels for Mesoamerica as a whole and present in parallel columns the chronological labels for the local KaminaIjuyu, Guatemala and Chalchuapa, El Salvador archaeological sequences. Locating the five ceramic traditions and one ceramic sphere I will approach this task by starting in the northwestern part of our area of concern and proceeding to the southeastern limits of this area. The ceramic traditions will be analyzed first and the ceramic sphere last. The Naranjo Ceramic Tradition. This utilitarian ceramic tradition is confined to the south coast (Pacific) of southeastern Chiapas, Mexico, and the western half of the south coast of Guatemala (see Map 1). The region is usually referred to as the "Soconusco" in Mesoamerican literature. It runs from Mapastepec, Chiapas to the river Naranjo on the southwest coast of Guatemala. Hatch (1988:154) begins the Naranjo tradition in the Early Preclassic Arevalo Phase or earlier (early Middle Preclassic on Table 1) and persists until about 950 A.D. at the close of the Terminal Classic Period. The publications relevant to this ceramic tradition, as well as the other ceramic traditions, are grouped separately in the bibliography at the end of this article. The language affiliation for this region was probably Mixe (Clark 1991:13; Lowe 1977:199202; and Kaufman 1976). The Achiguate Ceramic Tradition. Map I shows this tradition as confined to the area of three rivers on the south coast of Guatemala. The three rivers from west to east are the Coyolate, the Achiguate, and the Maria Linda. The Achiguate ceramic tradition lasted from the Las Charcas phase to the Amatle R phase (900 B.C. to A.D. 600). The language affiliation of the Achiguate group is very problematic but a reasonable speculation would be proto-Lenca(?). Map I Development of the Ceramic Traditions during the Middle Preclassic Period, 900-250 B.C. The Las Vacas Ceramic Tradition. During the Providencia Phase (450-200 B.C.) this ceramic tradition was located in the central highland departments of Guatemala, Sacatepequez, and Chimaltenango in Guatemala (see Map 1). In the following Verbena Phase the Las Vacas tradition was restricted to the department of Guatemala (Hatch 1988:156). The duration of the Las Vacas ceramic tradition is from about 450 B.C. until it disappears abruptly around 150 A.D. and is replaced by the Solano ceramic tradition (Hatch ibid., pages 15756). Edmonson (1988:103,123,189, and 264) assigns Proto-Xinca as the probable language affiliation of KaminaIjuyu residents. Thus the Las Vacas ceramic tradition people may have been familiar with the ProtoXinca language. The Solano Ceramic Tradition. Northwestern highland Guatemala, in the area of present day Quiche and Cakchiquel Maya peoples, was the homeland of the creators of the Solano Ceramic Tradition (see Map 1). The history of the Solano Ceramic Tradition begins as early as 900 B.C., if not earlier, and persists to 950 A.D. and perhaps to the Spanish Conquest (Hatch op. cit., pp. 158,165). The language affiliation appears to be Quiche Mayan from the beginning to the end of this tradition (Josserand 1975: Fig. Q. The Uapala Ceramic Tradition. This ceramic tradition is not as well studied as the above examples but involves eastern El Salvador and western Honduras (Andrews V 1976:180-81 and Baudez 1986:339 (see Map 2). Typical archaeological sites assigned to this Uapala Ceramic Tradition are Quelepa in eastern El Salvador, Copan, Yarumela, Los Nararijos, and Santa Rita in Honduras (Demarest and Sharer 1986:21213). This loosely defined Uapala Ceramic Tradition dates between ca. 500 B.C. to A.D. 900. The Proto-Lenca and Proto-Jicaque languages share the same territory as the Uapala Ceraimic Tradition. According to Edmonson (198 8:123) the Jicaque calendar began 21 December 57 B.C. and is a typical example of a Mesoamerican calendar. The Miraflores Ceramic Sphere. Willey, Culbert, and Adams 1967:306 define a ceramic sphere as follows: "The concept of ceramic sphere was defined to emphasize a high degree of content similarity between complexes. A ceramic sphere exists when two or more complexes share a majority of their most common types. Whereas the horizon need imply no more than a few connections at the modal level, the sphere implies high content similarity at the typological level." Based on the above definition of a ceramic sphere Demarest and Sharer (1986) and Hatch (1988) have mapped a Miraflores ceramic sphere covering eastern highland and coastal Guatemala and western E I Salvador (see Map 2 and 3). The time span for this ceramic sphere is between 250 B.C. and A.D. 150. The Miraflores, Ceramic Sphere represents the regional interaction between the Las Vacas and Achiguate Ceramic Traditions. This situation would imply a possible Xinca-Lenca language affiliation for the Miraflores Ceramic Sphere. Besides a sharing of ceramic ideas there is also a sharing of ideas in figurines, sculpture and iconography, censer complexes, lithic assemblages, and site layouts. Demarest and Sharer (1986:220) conclude: Such a sharing of ideas ... suggests that the artifactual patterns could actually reflect a culturally-unified population in the Late Preclassic period-possibly a single linguistic or ethnic group. This hypothesis of an ethnically and/or linguistically unified southeast highland culture area is suggested by: 1) close similarities in most aspects of the artifactual assemblages at each site; 2) clear differences with sites outside of the southeast highland region; and 3) the negation by [Neutron] activation analysis of the hypothesis that mass production and long-distance trade were the primary causes of the shared ceramic features. Indeed, if there is any relationship, however imperfect, between ethnic or linguistic patterns and material culture, then the degree of commonality in the material culture of these sites is sufficient to imply that a single ethnic or even linguistic group occupied the entire region in the Late Preclassic period. . .. Correlation Problems for the Book of Mormon. First, it should be pointed out that the Naranjo Ceramic Tradition, The Achiguate Ceramic Tradition, and the Solano Ceramic Tradition were all in place before the arrival of the Lehi colony in Ancient Mesoamerica. These ceramic traditions probably represent indigenous or native populations that would be encountered by the Lehi colony people. Since Kaminaljuyu is the proposed site of Nephi in our model of Book of Mormon geography, our focus will be on this site and its interaction with other nearby areas. There was a virtual absence of ceramics and obsidian at Kaminaljuyu prior to the Arevalo and Las Charcas phases (1150-450 B.C.) according to Wetherington (1978:190). He points out that there were no mounds, a lack of civic architecture, and surprisingly few occupational components (Libid., page 123). During the Las Charcas phase (900450 B.C.) KaminaIjuyu became an incipient regional center with a population of about 1000 individuals (Michels 1979:135). There is evidence of household stratification and the houses were located near a small lake that existed at Kamina]juyu during the Arevalo and Las Charcas phases (ibid., Figure 43). Wetherington believes that the initial settlement of Kaminaluyu resulted from a population expansion from the southern piedmont and coastal area of Guatemala (gp. cit., page 190). Demarest and Sharer (1986:213-14) see many similarities in the Arevalo and Las Charcas ceramic types to the Colos and Kal ceramic complexes at Chalchuapa, El Salvador (see Map 3). These ceramic similarities include examples of Usulutan pottery that probably originated at Chalchuapa according to Demarest and Sharer. These facts would suggest that the people involved in the first settlement of Kaminaljuyu were of Proto-Lenca speech. When Nephi and his party arrived at Nephi, they probably represented no more than two dozens souls. They were a definite minority if the population of Kamina1juyu at the time of their arrival was around 1,000 individuals (see above). It would seem apparent that Nephi and his party made friends with the local population. Nephi obviously was received with high regard since he was made a king (2 Ne. 5:18). Would Nephi be made a king over just his own people who were vi-ru fi-ui in n"tr i-r? As noted above during the Providencia phase (450-200 B.C.), the Vacas Ceramic Tradition at Kaminaljuyu spread into the area of present-day Guatemalan departments of Guatemala, Sacatepequez, and Chimaltenango with Guatemala City, Antigua, and Chimaltenango being the main communities today in these three departments. During the Verbena phase (200-1 B.C.) the Las Vacas Ceramic Tradition was restricted to just the department of Guatemala. This archaeological situation parallels the Book of Mormon account in that around 200 B.C., Mosiah led some Nephite followers from Nephi to Zarahemla, and just a few years later a small party of Nephites under the leadership of Zeniff returned to the city of Nephi. Perhaps Mosiah's Nephites came from the departments of Guatemala, Sacatepequez, and Chimaltenango and Zeniff's party returned to occupy an area in the department of Guatemala. As the Lamanites crowded into and surrounded the Nephites of King Zeniff, Noah, and Limhi, we would expect this situation to be reflected in the archaeological record of the central highlands of Guatemala. Sorenson (1985:221-26) suggests that the Book of Mormon lands of Nephi, Shemlon, Middoni, and Ishmael be located in Kaminaljuyu, Arnatitlan, Antigua, and Chimaltenango respectively (see Figures I and 2). The Pennsylvania State archaeological project defined Chiefdoms at Kaminaljuyu, Amatitlan, and Chimaltenango (Figure 1). However, they did not investigate the Antigua area and this area needs archaeological investigation. The language of the Quiche Maya was not directly involved in the Kamina1juyu area during the period of Nephite occupation. Marion Hatch (1988:162-64) in summarizing the domestic pottery traditions of Prehistoric Guatemala concludes that in the Protoclassic or Santa Clara period (150-300 A.D.) a new group completely replaced the previous people in the valley of Guatemala. These new people were Quiche Maya speakers. The best evidence for this drastic change comes from Kaminaljuyu. The direction of this takeover is to the northwest in the Guatemalan highlands. More specifically, the area from Lake Atitlan north to Huehuetenango is the source of these Quiche Maya invaders. Hatch also points out that the Protoclassic development in Belice and the eastern Peten of Guatemala did not originate in an invasion from El Salvador as previously thought but was in part a native development and in part an influence on the elite leadership of the area from the same Quiche Mayan group of highland Guatemala. Conclusions The model of Book of Mormon geography being developed suggests that of the five ceramic traditions and one ceramic sphere discussed above (see Maps 1-3), only the Las Vacas Ceramic Tradition fits the time and place requirements of our model. The Las Vacas Ceramic Tradition in time interacts strongly with the Achiguate Ceramic Tradition to form the Miraflores Ceramic Sphere. This suggests that the peoples of the Achiguate tradition were friendlier to the residents of Kaminaljuyu and the valley of Guatemala. It also implies that these friendlier ties in time involved western E 1 Salvador. The interaction of the Kaminaljuyu peoples with the peoples Naranjo and Solano Ceramic Traditions were much less intense and probably not so friendly. The Uapala Ceramic Tradition of eastern El Salvador and western Honduras was even more remote to the inhabitants of the valley of Guatemala during Preclassic, Protoclassic, and Early Classic or during Book of Mormon times. Kaminaljuyu is looking better all the time as a good candidate for the city of Nephi. References Introduction Andrews V.E. Wyllys. 1977. The Southeastern Periphery of Mesoamerica: A View from Eastern El Salvador. In Social Process in Mgya Prehis!M: Studies in Honor of Sir Eric lboMpson, ed. by Norman Hammond, pp. 11334. Academic Press: New York. Borhegyi, Stephan F. 1965a. Archaeological Synthesis of the Guatemalan Highlands. Handbook of Middle American Indians, vol. 2:3-58. University of Texas Press: Austin. 1965b. Settlement Patterns of the Guatemalan Highlands. Handbook of Middle American Indians vol. 2:59-75. University of Texas Press: Austin. Campbell, Lyle. 1977. Ouichean Linggistic Prehisim. University of California Publications in Linguistics, No. 81. Carmack, Robert M. 1973. Ouichean Civilization: The Ethnohistoric, Ethnogrgphic, and Archaeological Sources. University of California Press: Berkeley and Los Angeles. Coe, Michael D. & Kent V. Flannery. 1967. Early Cultures and Human Ecology in South Coastal Guatemala. Smithsonian Institution, Contributions to Anthropology, No. 3. Edmonson, Munro S. 1988. The Book of the Year: Middle American Calendrical Systems. University of Utah Press: Salt Lake City, UT. Hatch, Marion Popenoe. 1988. La Importancia de la Ceramica Utilitaria en Arqueologia, con Observaciones sobre la Prehistoria de Guatemala. Anales de la Academia de QpNrafia e Historia de Guatemala, torno LXH:151-70. Kaufman, Terrence S. 1976. Archaeological and Linguistic Correlations in Mayaland and Associated Areas of Meso-America. World Archaeology, No. 8:101-18. Lowe, Gareth W., Thomas A. Lee & Eduardo Martinez E. 1982. Izgpa: An Introduction to the Ruins and Monuments. Papers of the New World Archaeological Foundation, No. 31. New World Archaeological Foundation: Provo, UT. Michels, Joseph W. 1979. The Karninaluym Chiefdo Pennsylvania State University Press: State College, PA. Reina, Ruben E. & Robert M. Hill, 11. 1978. The Traditional Pottery of Guatemala. University of Texas Press: Austin, TX. Sharer, Robert J. 1974. The Prehistory of the Southeastern Maya Periphery. Current Anthropology, vol. 15, No. 2:165-87. Wallace, Dwight T. & Robert M. Carmack, eds. 1977. Archaeology and EthnohistoKy of the Central Quiche Institute for Mesoamerican Studies, State University of New York: Albany, New York. Willey, Gordon R., T. Patrick Culbert & Richard E.W. Adams. 1967. Maya Lowland Ceramics: A Report from the Guatemala City Conference. American Antiguity, vol. 32:289-315. The Naraixio Ceramic Tradition Clark, John E. 1991. The Beginnings of Mesoamerica: Apologia for the Soconusco Early Formative. In The Formation of Cgmplex Society in Southeastern Mesoamerica, ed. by William R. Fowler, Jr. CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL. Coe, Michael D. 1961. La Victoria: An Early Site on the Pacific Coast of Guaternal . Harvard University, Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Papers, vol. 53. Coe, Michael D. & Kent V. Flannery. 1967. Early Cultures and Human Ecology in South Coastal Guatemala. Smithsonian Institution, Contribution to Anthropology, No. 3. Ekholm, Susanna M. 1969. Mound 30a and the Early Preclassic Ceramic Seguence at Izapa, Chigpas, Mexico. Papers of the New World Archaeological, No. 25. New World Archaeological Foundation: Provo, UT. Hatch, Marion Popenoe. 1987. Proyecto Tiquisate: Recientes Investigaciones Arqueologicas en la Costa Sur de Guatemala. Cuadernos de Investigacion, No. 2. Universidad de San Carlos, Guatemala. Lowe, Gareth W. 1977. The Mixe-Zoque as Competing Neighbors of the Early Lowland Maya. In The Origins of Mgya Civilization, ed. by Richard E. W. Adams. A School of American Research Book. University of New Mexico Press: Albuquerque, NM. Shook, Edwin M. & Marion Popenoe Hatch. 1979. The Early Preclassic Sequence in the OcosSalinas La Blanca Area: South Coast of Guatemala. In University of California Archaeological Research Facilijy, Contributions 41:143-95. The Achiguate Ceramic Tradition Demarest, Arthur A. 1986. The Archaeology of Santa Leticia and the Rise of Maya Civilization. Middle American Research Institute, Publication 52. Tulane University: New Orleans, LA. Demarest, Arthur A. & Robert J. Sharer. 1986. Late Preclassic Ceramic Spheres, Culture Areas, and Cultural Evolution in the Southeastern Highlands of Mesoamerica. In 71be Southeast Maya Periphpa, ed. by Patricia A. Urban and Edward M. Schortman. University of Texas Press: Austin, TX. Shook, Edwin M. & Marion Popenoe Hatch. 1978. The Ruins of El Balsaino. Journal of New World Archaeology, Vol. III, No. 1. Institute of Archaeology, University of California: Los Angeles, CA. The Las Vacas Ceramic Tradition Shook, Edwin M. 1951. The Present Status of Research on the Pre-Classic Horizons in Guatemala. In Civilization of Ancient America: Selected Pgpers of the 29th International Congress of Americanists, ed. by Sol Tax, pp. 93-100. University of Chicago Press: Chicago, EL. Shook, Edwin M. & Alfred V. Kidder. 1952. Mound E-Ill3, Kamina1juyu, Guatemala. Contributions to American Anthro .pology and HisIM, No. 53, Carnegie Institution of Washington, Publication 574, pp. 1-92. Washington, D.C. Wetherington, Ronald K., editor. 1978. The Ceramics of Kaminaligym, Guatemala. Pennsylvannia State University Press: University Park, PA. The Solano Ceramic Tradition Butler, Mary. 1962. A Pottery Sequence from the Alta Verapaz, Guatemala. In The MUa and their Neighbors, pp. 250-67. University of Utah Press: Salt Lake City, UT. Icon, A. & M. C. Amauld. 1985. Le Protoclassigue a La Laguni . Centre Nacional de la Recherche Scientifigue, Institut D'Ethnologie, Paris. Josserand, Judy K. 1975. Archaeological and Linguistic Correlations for Maya Prehistory. In Actas de XLI Congeso Internacional de Americanistas, vol. 1, pp. 501-10. Mexico City, D.F. Kidder, Alfred V., Jesse D. Jennings & Edwin M. Shook. 1946. Excavations at . Kaminaljuyu, Guatemala. Carnegie Institution of Washington, Publication 561. Shook, Edwin M., Marion Popenoe Hatch & J. K. Donaldson. 1979. Ruins of Semetabaj, Department Solola, Guatemala. Contributions of the Archaeological Research Facili1y, University of California, No. 41. Berkeley. Smith, A. Ledyard & Alfred V. Kidder. 195 1. Excavations at Nebaj, Guatemala. Carnegie Institution of Washington, Publication 594. Wauchope, Robert. 1975. Excavations at Zacualpa, El Quiche, Guatemala: An Ancient Provincial Center of the Highland Maya. Middle American Research Institute, Publication 39. Tulane University: New Orleans, LA. Woodbury, Richard B. & Audrey S. Trik. 1953. The Ruins of Zaculeu, Guatemala, Vols. I and 2. William Bird Press: Richmond, VA. The Uavala Ceramic Tradition Andrews, E. Wyllys, V. 1976. The Archaeology of Quelepa, El Salvador. Middle American Research Institute, Publication 42. Tulane University: New Orleans, LA. Baudez, Claude F. 1986. Southeast Mesoamerican Periphery: Summary Comments. In The Southeast Mpya Perij2hpa, ed. by Patricia A. Urban and Edward M. Schortman. University of Texas Press: Austin, TX Baudez, Claude F. & Pierre Becquelin. 1973. Archeologie de Los Naranios, Honduras. Mission Archeologique et Ethnologique Francaise au Mexique. Vol. H, Etudes Americanes: Mexico. Canby, Joel. 1949. Excavations at Yarumela, Spanish Honduras. PhD Dissertation, Dept. of Anthropology, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA. Cheek, Charles. 1983. Las Excavaciones en la Plaza Principal: Resumen y Conclusiones. In Introduccion a la AMueologia de Copan, Vol. 2. SECTUR, Tegucigalpa, Honduras. Dernarest, Arthur A. & Robert J. Sharer. 1982. The Origin and Evolution of the Usulutan Ceramic Style American Antiqui1y, 46:810-22. Demarest, Arthur A., V. Roy Switsur, & Reiner Berger. 1982. Dating and Cultural Associations of the PotBellied Sculptural Style. American Antiqqi~ty, 97:55771. Fash, William L., Jr. 1983. Deducing Social Organization from Classic Maya Settlement Patterns: A Case Study from the Copan Valley. In Civilization in the Ancient Americas: Essays in Honor of Gordon R. Willey, Richard M. Leventhal and Alan L. Kolata, eds., pp. 261-88. Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology,. University of New Mexico Press: Albuquerque, NM. Kennedy, Nedenia C. 198 1. The Formative Period Ceramic Sequence from Playa de los Muertos, Honduras. PhD Dissertation, Dept. of Anthropology, University of Illinois, Urbana-Champagne, IL. Harvard University, Cambridge, MA. Leventhal, Richard M. 1979. Settlement Patterns at Copan, Longyear, John M., 111. 1952. Coan Ceramics~ A Study o Honduras. PhD Dissertation, Dept. of Anthropology, Southeastern Mgya Pottery. Carnegie Institution of Washington, Publication No.597. Washington, D.C. TABLE 1 Mesoamerica Kaminaliuvu Chalghuapa Modern Period: 1810-present Colonial Period: 1520-1810 Late Postclassic Period: (Chinuatla Phase) Ahal Phase 1250-1520 Early Postclassic Period: Ayampuc Phase Matzin Phase 950-1250 Terminal Classic Period: Arnatle III Phase Payu Phase 800-950 Late Classic Period: Amatle H Phase Payu Phase 600-800 Middle Classic Period: Amatle I Phase Xocco Phase 400-600 Early Classic Period: Aurora Phase Vec Phase 300-400 Protoclassic Period: Santa Clara Phase Vec Phase 150-300 Terminal Preclassic Period: Arenal Phase Caynac Phase 1-150 A.D. Late Preclassic Period: Verbena Phase Caynac Phase 250-1 B.C. Middle Preclassic Period: IV: 450-250 Providencia Phase Chul Phase 111: 900-450 Las Charcas Phase Kal Phase Il: 1150-900 Arevalo Phase Colos Phase 1: 1350-1150 Tok Phase Early Preclassic Period: 111: 1650-1350 11: 1850-1650 1: 2500-1850