The Role of Demographic Variables and Acculturation

advertisement

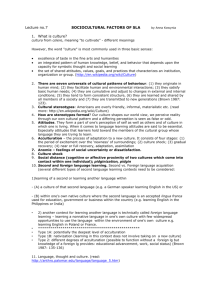

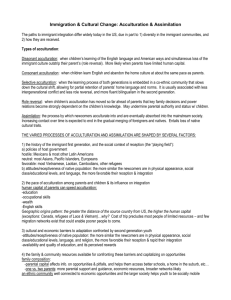

Acculturation Attitudes 1 The Role of Demographic Variables and Acculturation Attitudes in Predicting Sociocultural and Psychological Adaptation in Moroccans in the Netherlands Otmane Ait Ouarasse & Fons J. R. van de Vijver Tilburg University The Netherlands WILL BE PUBLISHED IN INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF INTERCULTURAL RELATIONS. Correspondence Information: Fons van de Vijver Department of Psychology Tilburg University PO. Box 90153 5000 LE Tilburg The Netherlands E-mail: fons.vandevijver@uvt.nl Fax: 00 31 13 466 2370 Acculturation Attitudes 2 Acculturation Attitudes 3 Abstract The goals of the present study were twofold, (i) to test the independence of the attitudes of second-generation migrants toward their culture of origin and toward the culture of the host society, and (ii) to test a path model in which these acculturation attitudes moderate and/or mediate the relationship between demographic factors (age, gender, occupation, education, and length of stay) and acculturation outcomes (including psychological adjustment, as measured by mental health and sociocultural acculturation as measured by school success, work success). Both hypotheses were to a large extent confirmed in a group of 155 second-generation Moroccans in the Netherlands. The results suggest that the two underlying dimensions of acculturation attitudes were largely independent across migrants and slightly negatively related within migrants; furthermore, there were some indications that ethnic culture was to some extent more liked in the personal domain and the host culture more in the public domain. Acculturation attitudes mediated the relationship between demographic variables and sociocultural adaptation. In turn, sociocultural adaptation mediated the relationship between acculturation attitudes and psychological adaptation. The results showed also that sociocultural and psychological adaptation had their own predictors; psychological adaptation was directly predicted by background variables while sociocultural adaptation was directly predicted by acculturation attitudes. Acculturation Attitudes 4 The Role of Demographic Variables and Acculturation attitudes in Predicting Sociocultural and Psychological Adaptation The current study examines two aspects of acculturation. The first involves the structure of acculturation attitudes. Specifically, the question addressed is whether attitudes (of second-generation Moroccans in the Netherlands) toward the ethnic and the host culture are independent. Independence of ethnic and host culture means that the scores on attitudes toward one culture are not related to the scores on the second culture; the correlation between the two scores is insignificant. The second involves the often claimed, but infrequently tested, moderating or mediating role of acculturation attitudes. A path model is tested in which acculturation attitudes moderate or mediate the relationship between background factors, such as gender and length of stay in the host country, and acculturation outcomes. Models of Acculturation Attitudes Two models of acculturation are dominant: The unidimensional model and the bidimensional model. In the unidimensional model, attitudes toward the culture of origin and attitudes toward the culture of the host society are dependent. There are two variants within the unidimensional model namely, the assimilation variant and the bicultural variant. According to the assimilation variant, complete absorption in the mainstream culture is the unavoidable outcome of migration, and cross-cultural travellers end up losing their ethnic feelings and cultural characteristics in favour of the embracement of the host culture (e.g., Gordon, 1964; Olmeda, 1979). The bicultural variant, on the other hand, views biculturalism, the simultaneous adherence to both cultures, as a possible outcome (e.g., Shadid, 1979; Wong-Rieger & Quintana, 1989). Although the bicultural variant is favoured over the Acculturation Attitudes 5 assimilation variant for making room for the possibility of actually managing cultural differences, it is criticised for failing to distinguish between real biculturalism, in which cross-cultural travellers wish to associate with both mainstream and minority culture, and double alienation, in which they wish to dissociate from both. The second model, known as the bidimensional acculturation model, considers ethnic and host identities as independent. Adherence to both identities yields “integration” (real biculturalism), adherence to none yields “marginalization” (double alienation), there is “separation” when one favours only one’s own ethnic identity, and finally there is “assimilation” when one favours only the host identity (e.g., Berry, 1974, 1984, 1994). Berry’s acculturation model has gained support and the four acculturation strategies turn out to have a good descriptive and explanatory power (Berry, 1997; Bochner, McLeod, & Lin, 1977; Lalonde & Cameron, 1993; Redmond, 2000; Sam, 1995). Despite this support, the model by Berry has its critics. While Boski (1998) and Weinreich (1998) consider the model by Berry to be too simplistic to account for the complexities of acculturation processes, Ward (1999) argued that the two underlying dimensions of cultural identity (i.e., attitudes toward minority culture and attitudes toward mainstream culture) are better predictors of acculturation outcomes than the four acculturation strategies. Other researchers (e.g., Arends-Tóth, 2003; Phalet, Van Lotringen, & Entzinger, 2000; Phalet & Swyngedouw, 2003) found evidence for the distinction between public and private domains in acculturation attitudes, while the bidimensional model assumes that acculturation attitudes are similar across life domains. Turkish migrants in the Netherlands were found to be more in favour of separation in the private domain and more in favour of integration in the public domain. Demographic Factors and Acculturation Attitudes Acculturation Attitudes 6 Research on generation status (i.e., first-, second-, third-, or later generation) and acculturation patterns suggests the existence of changes in cultural identifications over time. Montgomery (1992) showed that immigrants tend to develop stronger identifications with the host culture over generations. It has also been demonstrated that this tendency does not necessarily entail dissociation from one’s culture of origin; Maveras, Bebbington, and Der (1989) reported that second-generation Greeks in the United Kingdom identified more strongly with the host culture than their parents did but without dissociating from their own culture of origin, achieving thus balanced loyalties. Also interesting is the distinction between attitudinal and behavioural aspects of acculturation; it is argued that attitudinal and behavioural aspects of acculturation show distinct patterns of change over time, with attitudes often showing a stiffer resistance to change (Triandis, Kashima, Shimada, & Villareal, 1986; Wong-Rieger & Quintana, 1987). Gender may also be significantly related to acculturation attitudes. There is evidence that women are more assertive of their culture of origin (Harris & Verven, 1996; Liebkind, 1996; Ting-Toomey, 1981) and are slower than men at developing identifications with the host culture (Ghaffarian, 1987). Length of residence in a foreign culture has been proven to be positively associated with attitudes toward the host culture and negatively with attitudes toward ethnic culture (Cortes, Rogler, & Malgady, 1994). Educational level is also associated with acculturation attitudes; Suinn, Ahuna, and Khoo (1992) demonstrated that higher levels of education boost host culture identification. The claim that demographic factors have been reported to be significantly associated with acculturation attitudes should not be overstretched for such association may well differ across ethnic groups. Acculturation Outcomes Acculturation researchers have used a multitude of variables as relevant acculturation Acculturation Attitudes 7 outcomes, but these variables can be systematically grouped under two major types: psychological outcomes and sociocultural outcomes (Ward, Bochner, & Furnham, 2001). Psychological adaptation is mainly studied in the stress and coping tradition and is a matter of mental health and of general satisfaction with life in the host milieu. Sociocultural adaptation, on the other hand, is studied in the culture learning tradition, and is mainly a matter of successful participation in the host society. It has been argued that psychological adaptation and sociocultural adaptation are linked; their correlations have been reported to be in the range [.4, .5] (Berry, 2003). Ward and Kennedy (1999) found that psychological and sociocultural adaptation outcomes were positively correlated. It was further found that the strength of the association between psychological and sociocultural adaptation was positively related to the degree of cultural proximity and of integration in the social host milieu (Ward, 1999; Ward & Kennedy, 1996; Ward, Okura, Kennedy, & Kojima, 1998; Ward & Rana-Deuba, 1999). Demographic Factors and Acculturation Outcomes Age has been reported to be significantly, albeit inconsistently, related to acculturation outcomes (see Church, 1982, for a review). Beiser et al. (1988) argued that adolescence and old age are high-risk periods compared to other periods; adolescence was believed to be fraught with psychological problems due to identity formation and development, while old age was believed to be fraught with learning difficulties that impair sociocultural adaptation and ultimately jeopardize general satisfaction with life in the host milieu. Padilla (1986), on the other hand, found that older Japanese and Mexican migrants in the United States showed higher levels of psychological distress. Research on the relationship between generation and acculturation outcomes has also reported inconsistent results. Furnham and Li (1993) found that first-generation Chinese Acculturation Attitudes 8 migrants to Britain experienced more psychological distress than their second-generation counterparts. In contrast, Heras and Revilla (1994) reported poorer self-concepts and lower self-esteem among second- than among first-generation Filipino-Americans. The association between length of stay in the host country and acculturation outcomes is not yet clear. The U-curve hypothesis according to which cross-cultural transitions start with enjoyment and euphoria, followed by crisis, recovery, and finally adjustment (Lysgaard, 1955; Gullahorn, & Gullahorn, 1963), has not been fully supported. The earlier support for the U-curve may have been influenced by the inadequacy of cross-sectional designs to account comprehensively for changes over time. Although the hypothesis is not completely abandoned, it is now believed (Ward et al., 2001) that the patterns of the association between length of stay and acculturation outcomes depend on the type of migrating group (sojourners, immigrants, refugees) and also on whether acculturation outcomes are cognitive, behavioural, or affective (Ward et al., 2001). The association between educational level and acculturation outcomes has also been investigated. Better-educated cross-cultural travellers reported stronger involvement with the host culture and better sociocultural and psychological adaptation due to their relative resourceful cultural learning (Jayasuriya, Sang, & Fielding, 1992) than less educated migrants. Level of education was also reported to be positively associated with self-esteem (Pham & Harris, 2001). However, highly educated migrants who experience downward social mobility (Dohrenwend & Dohrenwend, 1974) or blocked upward mobility (Aycan & Berry, 1996; Beiser, Johnson, & Turner, 1993) because of their minority status showed higher psychological dysfunction than less educated migrants. Research on the relationship between gender and acculturation outcomes has yielded inconsistent results. Beiser et al. (1988) and Furnham and Shiekh (1993) found that females were prone to experiencing a relative lack in involvement with the host culture and to Acculturation Attitudes 9 possessing fewer host culture-specific skills, and were also likely to experience more psychological problems than males. Boski (1990, 1994), on the other hand, reported a better psychological adjustment among females than among males. Still, other studies reported no gender differences in psychological adjustment (Furnham & Tresize, 1981; Nwadiora & McAdoo, 1996). It is clear from the above that studies examining relationships between demographic factors and acculturation outcomes are still fraught with inconsistencies. We suspect these inconsistencies to be the result of either weak effects, or the overlooking of crucial moderating variables in the studies, or a combination of both. Acculturation Attitudes and Acculturation Outcomes Research on the association between acculturation attitudes and acculturation outcomes, which seems to focus mainly on psychological adaptation as an outcome variable, has yielded inconsistent results. Singh (1999) demonstrated that stronger identification with the host culture was related to higher levels of stress, while Padilla (1986) showed that it was related to less stress. A similarly inconsistent pattern was found for depression; whereas Ghaffarian (1987) demonstrated that stronger identification with the host culture was related to less depression, Kaplan and Marks (1990) demonstrated that it was related to more depression. Buriel, Calzada, and Vasquez (1982) showed that a balanced identification with both cultures tended to co-occur with psychological adjustment. Ward and Kennedy (1994) found that strong host culture identification was associated with more sociocultural adjustment, and that strong ethnic identification was associated with fewer psychological adaptation problems. Other researchers used the acculturation strategies developed by Berry and found substantial and quite consistent evidence for the association between acculturation strategies Acculturation Attitudes 10 and outcomes. The strategies of integration and separation were related to better psychological adjustment, while marginalization and assimilation were related to lower levels of psychological adjustment (Berry & Annis, 1974; Berry, Kim, Minde, & Mok, 1987). Acculturation Context of Moroccans in the Netherlands The first Moroccans arrived in the Netherlands some forty years ago. Dutch labourintensive industries needed workers and Morocco had plenty of those, ready and cheap. Now, and as a result of a long recruitment period, family reunion, new marriages and births, the Moroccan community in the Netherlands has grown in size and now counts some 280,000 individuals, of which about 40% are born in the Netherlands. Most members of the second generation are still at school. Up to 1998, only 2% of Moroccans are thought to have completed higher professional or university education, compared to 3%, 14%, 12%, and 26% for Turks, Surinamese, Antilleans, and Dutch, respectively (Martens, 1999). With 22% registered unemployed, Moroccans also have one of the highest unemployment rates (Martens, 1999). The image of young Moroccans in the Dutch media and public discourse is far from bright; they are often associated with delinquency, separation, and resistance to change (Hagendoorn, 1991). Although Moroccans are found in various areas of the country, they tend to concentrate in the largest urban centres. Many relatives live close to one another. This is dictated by both the need for mutual support and for senior Moroccan women, mostly housewives, to have frequent contacts with one another. Islam is the religion of all of Moroccans in the Netherlands. Mosques, which did not exist in the Netherlands before, have been built. They serve both as a place for worship for the old, and a place for teaching Arabic, the language of the Scripture, to the very young. Mosques are not as salient in the Netherlands as in Morocco because they do not have a Acculturation Attitudes 11 minaret and because the call for prayer is not allowed. There is a disagreement as to whether Islam also plays an important role in the lives of Moroccan youth in the Netherlands. Buijs (1993) and Pels (1998) argue that Islam remains an important constituent of their identity although, in comparison to their parents, they have a more liberal interpretation of it. Hypotheses The model tested in the present study summarises our reading of the literature. The inconsistencies reported in the literature, we suspect, are the result of weak effects or the overlooking of pertinent moderating variables. Path analysis is conducted for the testing of the mediating/moderating role of acculturation attitudes. The current study addresses school success and work success as indicators of sociocultural adaptation, and mental health as an indicator of psychological adaptation. Although we acknowledge that the relationship between aspects of sociocultural adaptation and aspects of psychological adaptation might be reciprocal, we restrict our hypothesis in this study to the flow of effects from sociocultural adaptation to psychological adaptation. Participants in the current study are secondgeneration Moroccans who have followed Dutch schooling and know the Dutch language and culture well. In this group, the level of and variation in experienced stress is assumed to be more modest than in a group of first-generation Moroccans. As a consequence, we do not expect the experienced stress to exert a strong influence on sociocultural adaptation. We further hypothesize that for reasons of temporal priority, school success would precede work success, and that mental health is a more or less long-term outcome. The effects are then expected to flow from demographic factors to acculturation attitudes to school success to work success, and finally to mental health. Method Participants Acculturation Attitudes 12 The sample consisted of 155 second-generation individuals of pure Moroccan parentage. Their parents originated from different provinces in Morocco; the participants lived in different provinces in the Netherlands. They were aged between 18 and 25, with a mean age of 21.68 years (S = 2.29). Of these, 84 were males and 71 females;. 77 were fulltime students, 71 full-time workers and 4 unemployed. All full-time students happened to have a part-time work experience. Full-time workers answered school questions on the basis of their past schooling. All participants were fluent in Dutch, while. 54.2% had Moroccan Arabic as mother tongue, and 44.5% had a variety of Berber as mother tongue. All participants reported very good mastery of their respective mother tongues. 85.8% had a Dutch nationality. The average length of residence in the Netherlands was 17.55 year (S = 6.21). They all reported to be Moslem (see Table 1 for descriptives). No sampling frame is available in the country that would allow exact proportional representation of second-generation Moroccans in the Netherlands. However, age, gender, and profession are present in the sample in ways that would provide the necessary variation to study acculturation-related variables. Although the age group 18-25 consists mainly of students (many Moroccan students in the Netherlands are made to follow a longer route toward their degrees), we included in the sample as many students as workers. It is true that some sampling was school-based, but some sampling was also Mosque-based. Twelve gatekeepers from different professions and regions al as well as geographic backgrounds helped in the search for and recruitment of participants. Instruments Attention was paid to the validity of the tests constructed for the study from the very beginning. Prior to the main study, we conducted a round of unstructured interviews and administered a round of questionnaires. We developed clear operationalizations of the Acculturation Attitudes 13 concepts. Items were developed that fitted the concepts’ definitions. Statistical analyses were then performed that provided information on item quality and item clusters. Cronbach’s alphas are reported in Table 1. Acculturation attitudes. This is a 68-item measure of the extent to which participants like or dislike elements of Moroccan culture and of Dutch culture. There is a one-to-one correspondence between the items in each culture. Scores vary from not at all (1) to very much (5). The scale contains items pertaining to twelve cultural domains namely, food (e.g., “Do you like the way Moroccan food is prepared?”), home (“Do you like the Moroccan home atmosphere?”), clothing (“Do you like Moroccan female clothing?”), arts and festivities (“Do you like Moroccan humour?”), language (“Do you like the Moroccan language?”), family (“Do you like parent-child relationship in the Moroccan family?”), friends (“Do you like boyfriend-girlfriend relationships in Moroccan culture?”), strangers (“Do you like the way Moroccans treat persons they do not know?”), politics (“Do you like Moroccan media?”), and religion (“Do you like interpersonal relationships in Islam?”). Mental health. This is an 18-item measure of mental health. It is a mixture of elements from the Depressive Tendencies Scale (Alsaker, 1990), complemented with a list of psychosomatic complaints based on a slightly modified version of the World Health Organization Cross-National Survey of Psychological and Somatic Symptoms (1988). The psychosomatic items employ a frequency format, with five response options ranging from never (1) to most of the time (5). The scale contains items such as “I feel I don’t have much to be proud of”, “Sometimes I think that life is not worth living” and “I feel difficulty getting to sleep”. School Success. This is an 11-item measure of how well participants do at school. It contains elements pertaining to cognitive and social aspects of school achievement. The scale contains items like “I am satisfied with my marks” and “I have a good reputation among my Acculturation Attitudes 14 classmates”. The scale is unifactorial and its factor accounts for 40.86% of the total variance. Work Success. This is a 12-item measure of how well participants do at work. It contains items pertaining to professional aspects of work success such as task completion (“My supervisor is pleased with the work I do”) and items pertaining to the social aspect of work (“I have a good reputation among my co-workers”). The scale is unifactorial and the factor accounts for 35.48% of the total variance. < Insert Table 1 about here > Procedure Data were collected by means of questionnaires. Informal networks of communication inside the Moroccan community were called upon for the recruitment of participants. The goal of the research was explained to the participants and the financing body explicitly named. Participants were told that the information provided in the questionnaires would remain confidential and that they were free not to contribute to the research. They were paid for their contribution. Four native speakers translated the English template of the questionnaire into Dutch. Versions were compared and differences (which were small) were resolved through discussion. Data Analysis Acculturation attitudes. Factor analysis is conducted for the exploration of the structure of acculturation attitudes. Assumptions about the use of path analysis. There are 155 participants and 10 observed variables. The ratio of cases to variables is 15:1, which is adequate for our analysis purposes. The very few missing values were estimated using regression logic. A visual inspection showed that the distribution of all scores was fairly normal. The skewness statistic for all variables fell within the range [-.88, .10]. These data checks supported the use of path Acculturation Attitudes 15 analysis. Hypothesised model. Two models were simultaneously tested namely, a moderation model and a mediation model. The hypothesised model consisted entirely of observed variables. Attitudes toward ethnic culture and attitudes toward host culture were assumed to be unrelated. Sociocultural outcomes (school success and work success) were assumed to precede psychological outcomes (mental health). All background variables were allowed to be interrelated. Both the moderation and mediation models allowed background variables to be associated with acculturation attitudes and, in turn, acculturation attitudes were allowed to be associated with acculturation outcomes. While the moderation model allows background variables to correlate directly with acculturation outcome variables, the mediation model does not (Baron & Kenny, 1986). Results Independence of Acculturation Attitudes Scree test, eigenvalue, and interpretability criteria suggested the extraction of two factors (eigenvalues: 8.66, 7.99; see Figure 1). The two factors explained 24.44% of the variance. Three-, four- and five-factor solutions with more factors were not clearly interpretable. Factor loadings (Oblimin-rotated) are presented in Table 2. Out of the initial 68 items, three (Moroccan girlfriend-boyfriend relationship, Bible, and Christian prayer, see Table 2) had very low communalities and therefore loaded on none of the factors. With the exception of two items (Moroccan music and Moroccan feasts, see Table 2), all remaining 32 ethnic items loaded together on one factor that we called “attitudes toward ethnic culture”. The remainder of the scale items, with the exception of two (Bible and Christian prayer), loaded on a second factor that we called “attitudes toward host culture”. It could be concluded that acculturation attitudes boil down to two factors namely, attitudes toward Acculturation Attitudes 16 ethnic culture and attitudes toward host culture. The results also pointed to the orthogonality of the factors (r = .03). The acculturation items about the ethnic and host cultures were formulated in an identical way (e.g., “Do you like Moroccan table manners?” and “Do you like Dutch table manners?”). The identical formulations enabled the computation of intra-individual correlations between the responses at the ethnic and host items (34 items per culture). The average correlation (across all 155 participants) was -.21 (S = .24), which suggests that the participants saw the two cultures as somewhat incompatible. <Insert Table 2 and Figure 1 about here> Major Likes and Dislikes A close look at the descriptives showed that there is a pattern in the major likes and dislikes across both cultures, particularly for the extreme scores. Food and religion represented both the items most liked in ethnic culture and most disliked in the host culture. The same is to some extent true for politics; politics tended to be the participants’ most disliked items in ethnic culture and its human rights aspect the mostly liked in Dutch culture (Tables 3 and 4). <Insert Tables 3 and 4 about here> The Moderating/Mediating Function of Acculturation Attitudes Model estimation. The hypothesised model [χ2(3, N = 155) = .55, p = .91] presents a very good fit to the sample data (GFI = 1.00; AGFI = .99; RMSEA = .00; see Figure 3). All fit indices pointed to a good fit between the hypothesised model and the sample data. Acculturation Attitudes 17 Model assessment. Most parameter values exhibited the expected signs, which provides strong support for the adequacy of the hypothesised model of Figure 2 (see also Table 5 for correlations). However, not all parameter estimates were statistically significant. Although this information might be due to the limited sample size (Byrne, 2001; Hoelter 1983), it still could point to the possibility that some hypothesised paths are relatively unimportant to the model. < Insert Table 5 and Figure 2 about here > Model modification. As could be expected, on the basis of the very good overall fit, no modification indices were significant. However, an examination of the model’s parameter estimates showed that 28 parameters were not significant (8 covariances, and 20 regression paths; one observed variable, education, was deleted). A new model (Figure 3) in which only significant paths are represented [χ2(22, N = 155) = 16.42; p = .79] showed a very good fit (GFI = .98; AGFI = .95; RMSEA = .00). Obviously, this model runs the risk of capitalizing on the particulars of the current sample. The explained variances for the modified model are .09, .07, .12, .20, and .19 for attitudes toward host culture, attitudes toward ethnic culture, school success, work success, and mental health, respectively. < Insert Figure 3 about here > It can be concluded that attitudes toward ethnic culture and attitudes toward host culture moderate the relationship between background and acculturation outcomes. A remarkable feature of the data is that acculturation attitudes do not influence psychological adjustment directly, but only indirectly via sociocultural adjustment. Attitudes toward ethnic Acculturation Attitudes 18 culture and attitudes toward host culture were independent and affected mental health only via school success and work success. Attitudes toward ethnic culture mediated the relationship between both age and length of stay and sociocultural adaptation; similarly, attitudes toward host culture mediated the relationship between gender and sociocultural adaptation. Length of stay, occupation, and gender affect mental health directly, with occupation affecting also work success directly (see Figure 4 for a tentative summary of these patterns). Positive attitudes toward ethnic and host cultures have positive effects on school and work success; in turn, work success significantly diminishes distress risks. The positive attitudes toward ethnic culture are diminished by both age and length of stay; the older the participants and the longer their stay in the Netherlands, the less positive they are toward their ethnic culture. Young Moroccan females tend to be more positively appreciative of Dutch culture than their male counterparts. As to the direct effects of background variables on distress, it was found that females, workers, and those with a shorter stay are more prone to distress than males, students, and those with a longer stay. <Insert Figure 4 about here> Discussion The goals of the present study were (i) to test the independence of attitudes toward ethnic culture and attitudes toward host culture, and (ii) to test a path model in which these moderate the relationship between demographic factors (age, gender, occupation, and length of stay) and acculturation outcomes (sociocultural and psychological). Both hypotheses were to a large extent confirmed. Acculturation Attitudes 19 Independence of Acculturation Attitudes Attitudes toward ethnic culture and attitudes toward host culture are independent. This result is line with the bidimensional model of acculturation (Berry, 1974, 1984, 1994). According to this model, a young Moroccan may well choose to identify with or dissociate from a culture without constraining identification or dissociation possibilities with the second culture. Future studies will have to determine to what extent and under which circumstances this independence of attitudes generalizes to behaviour. The results on the major likes and dislikes hint to the possibility that migrants’ preferences vary across cultural domains. They might prefer separation in one area of culture and integration or assimilation in another area. Although the participants seemed to adopt the separation strategy in the areas of food and religion, they nevertheless opted for assimilation in the area of politics; a similar pattern was reported by Arends-Tóth (2003). In sum, the results suggest that the two underlying dimensions are largely independent across migrants and slightly negatively related within migrants; furthermore, there were some indications that ethnic culture might be more liked in the personal domain and the host culture more in the public domain. The Time Factor The longer young immigrants reside in a host country, the easier it should become for them to understand and deal fruitfully with the new culture and its challenges. By being in the Netherlands for only a short time, young Moroccans may find it difficult to get along comfortably with the streams of novelty facing them. Even with enough ethnic support, newly landed immigrants need that relative relaxation which only familiarity would bring. So day in day out, immigrants are expected to shed some of the malaise experienced early in Acculturation Attitudes 20 their immigration history. Situations that would have been appraised as stressful in the early stages of residence would now, and maybe by sheer familiarity, fail to alert the immigrant or even trigger a stress process. The finding that length of stay predicts attitudes toward ethnic culture negatively might be the expression of a real change in preference due to the immigration experience and exposition to an alternative life-style. This negative effect on attitudes toward ethnic culture is shared by age; the results showed that within this age group of older adolescents and young adults, the older the immigrants are the less favourable to their own culture. Two possibly complementary explanations can be envisaged. First, there may be a slow movement away from Moroccan culture as a consequence of involvement and immersion in the public sphere. Moroccan work values, for instance, may not be functional in a Dutch-managed workplace and might be abandoned. The character of culture as a collective coping and survival strategy may take over its essential and emotional value, and the pressure to survive in an alien milieu might urge immigrants to steer away from their culture of origin. This slow movement away from the ethnic culture is in line with existing literature (e.g., Montgomery, 1992) and with the unidimensional acculturation model (Gordon, 1964). Second, older participants in this age group of the current study are more likely to have left school and are most probably paid fulltime workers with a salary. With this new status, the young worker is expected to take part in the parental household responsibility by providing for parents and younger siblings. The new responsibility can easily manifest itself in a decrease in liking for the source of the burden: Moroccan culture. The negative effects of occupation on mental health corroborate this explanation. The results showed that workers are more likely than students to be distressed. The Gender Factor Attitudes toward host culture is mainly dependent on gender. The results show that Acculturation Attitudes 21 females were more favourable toward the Dutch culture than males, which is not in line with research findings elsewhere (Ghaffarian, 1987; Harris & Verven, 1996; Liebkind, 1996; Ting-Toomey, 1981). An explanation for these results may be the comparative “attraction” of gender roles in Dutch culture for Moroccan women; Moroccan women seem to have more to gain from Dutch culture (e.g., more freedom and independence) while Moroccan males seem, in comparison, to have more to lose. Combining this with our finding that there are no gender differences on attitudes toward ethnic culture, it becomes clear that an explanation of the comparative appreciation of Dutch culture among Moroccan females does not reside in the contents of the Moroccan culture. It seems rather that Moroccan women appreciate Dutch culture for its instrumental value. A Moroccan young lady adhering unquestionably to the values in Moroccan culture might still perceive in Dutch culture a legitimate tool for the promotion of herself and her cultural values; more power and independence might be examples of such tools. Conclusion To sum up, the results suggest that the two underlying dimensions of acculturation attitudes were largely independent across migrants and slightly negatively related within migrants; besides, ethnic culture tended to be favoured more in the personal domain and the host culture more in the public domain. Acculturation attitudes mediated and moderated the relationship between background variables and sociocultural adaptation. In turn, sociocultural adaptation mediated the relationship between acculturation attitudes and psychological adaptation, which is in line with our expectations and previous findings (Ait Ouarasse & Van de Vijver, 2004a, 2004b, b). Ward and Kennedy (1993; see also Liebkind, 2001) argue that sociocultural adaptation is mainly a function of contact variables (such as education in the host country and length of stay), while psychological adaptation is mainly a function of Acculturation Attitudes 22 ethnic group variables (such as support networks). Our findings point to a slightly different role of both the host and ethnic culture in adaptation. In a previous study (Ait Ouarasse & Van de Vijver, 2004a) we found that sociocultural adaptation is split up into school success and work success and that different predictors were found for both types of success. Ethnic group variables were better predictors of school success and mainstream variables were better predictors of work success. The ethnic group variables examined were not instrumental, but support values such as the permissiveness to adjust. Analogously, we found evidence that the effect of the main culture on work success is not just instrumental. The perceived tolerance of the mainstream society toward ethnic group was a significant predictor of work success. The evidence of the current study indicating that attitudes toward both ethnic and host culture predict sociocultural adaptation can be interpreted along the same line. The role of the ethnic and host cultures cannot be reduced to their instrumental and supportive function, respectively. Although the model obtained presented a good fit to the data, a test of multigroup invariance is necessary before the model can be generalized to other groups and to other acculturation contexts. Acculturation Attitudes 23 References Ait Ouarasse, O., & Van de Vijver, F. J. R. (2004a). The role of acculturation context, personality and coping in the psychological adaptation of young Moroccans in the Netherlands. (in preparation) Ait Ouarasse, O., & Van de Vijver, F. J. R. (2004b). Structure and function of the perceived acculturation context of young Moroccans in the Netherlands, International Journal of Psychology. (in press) Alsaker, F. F. (1990). Global negative self-evaluations. Doctoral dissertation. Bergen, Norway: Faculty of Psychology, University of Bergen. Arends-Tóth, J. (2003). Psychological acculturation of Turkish migrants in the Netherlands. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Dutch University Press. Aycan, Z., & Berry, J. W. (1996). Impact of employment-related experiences on immigrants’ psychological well-being and adaptation to Canada. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Sciences, 28, 240-251. Baron, R., & Kenny D. (1986): The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 1173-1182. Beiser M., Barwick, C., Berry, J. W., da Costa, G. Fantino, A., Ganesan, S., Lee, C., Milne, W., Naidoo, J., Prince, R., Tousignant, M., & Vela, E. (1988). Mental health issues affecting immigrants and refugees. Ottawa: Health and Welfare Canada. Beiser, M., Johnson, P., & Turner, J. (1993). Unemployment, underemployment and depressive effects among South-Asian refugees. Psychological Medicine, 23, 731743. Berry, J. W., & Annis, R. C. (1974). Acculturative stress. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 5, 382-406. Acculturation Attitudes 24 Berry, J. W., Kim, U., Minde, T., & Mok, D. (1987). Comparative studies of acculturative stress. International Migration Review, 21, 491-511. Bochner, S. Lin, A., & McLeod, B. M (1979). Cross-cultural contact and the development of an international perspective. Journal of Social Psychology, 107, 29-41. Berry, J. W. (1974). Psychological aspects of cultural pluralism. Topics in Culture Learning, 2,17-22. Berry, J. W. (1984). Cultural relations in plural societies. In N. Miller & M. Brewer (Eds.), Groups in contact (pp. 11-27). New York: Academic Press. Berry, J. W. (1994). Acculturation and psychological adaptation. In A.-M. Bouvy, F. J. R. Van de Vijver, P. Boski, & P. Schmitz (Eds.), Journeys into cross-cultural psychology (pp. 129-141). Lisse, The Netherlands: Swets & Zeitlinger. Berry, J. W. (2003). Conceptual approaches to acculturation. In K. M. Chun, P. B.Organista, & G. Marin (Eds.), Acculturation: Advances in theory, measurement, and applied research (pp. 17-39). Washington DC: American Psychological Association. Berry, J. W. (1997). Immigration, acculturation and adaptation. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 46, 5-34. Boski, P. (1990). Correlative national self-identity of Polish immigrants in Canada and the United States. In N. Bleichrodt & P. J. D. Drenth (Eds.), Contemporary issues in cross-cultural psychology (pp. 207-216). Lisse, The Netherlands: Swets & Zeitlinger. Boski, P. (1994). Psychological acculturation via identity dynamics: Consequences for subjective well-being. In A.-M. Bouvy, F. J. R. Van de Vijver, P. Boski, & P. Schmitz (Eds.), Journeys into cross-cultural psychology (pp. 197-216). Lisse, The Netherlands: Swets & Zeitlinger. Boski, P. (1998). A quest for a more cultural and a more psychological model of acculturation. Paper presented at the XIV International Congress of the International Acculturation Attitudes 25 Association for Cross-Cultural Psychology, Bellingham, WA. Buijs, F. (1993). Leven in een nieuw land. Marokkaanse jongemannen in Nederland. Utrecht: Uitgeverij Jan van Arkel. Buriel, R., Calzada, S., & Vasquez, R. (1982). Relationship of traditional Mexican American culture to adjustment and delinquency among three generations of Mexican-American male adolescents. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 1, 41-55. Byrne, B. M. (2001). Structural Equation modelling with AMOS: Basic concepts, applications and programming. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum. Camilleri, C., & Malewska-Peyre, H. (1997). Socialization and identity strategies. In. J. W. Berry, P. R. Dasen, & T. S. Sarawathi (Eds.), Handbook of cross-cultural psychology: Vol 2. Basic processes and human development (pp. 41-67). Boston: Allyn & Bacon. Church, A. T. (1982). Sojourner adjustment. Psychological Bulletin, 91, 540-572. Cortes, D. E., Rogler, L. H., & Malgady, R. G. (1994). Biculturality among Puerto Rican adults in the United States. American Journal of Community Psychology, 22, 707-721. Dohrenwend, B. P., & Dohrenwend, B. S. (1974). Social and cultural influences on psychopathology. Annual Review of Psychology, 25, 216-236. Furnham, A., & Tresize, L. (1981). The mental health of foreign students. Social Science and Medicine, 17, 365-370. Furnham A., & Li, Y. H. (1993). The psychological adjustment of the Chinese community in Britain: A study of two generations. British Journal of Psychiatry, 162, 109-113 Furnham, A., & Shiekh, S. (1993). Gender, generational and social support correlates of mental health in Asian immigrants. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 39, 2233. Ghaffarian, S. (1987). The acculturation of Iranians in the United States. Journal of Social Psychology, 127, 565-571. Acculturation Attitudes 26 Gordon, M. M. (1964). Assimilation in American life. New York: Oxford University Press. Gullahorn, J. T., & Gullahorn, J. E. (1963). An extension of the U-curve hypothesis. Journal of Social Issues, 19, 33-47. Hagendoorn, L. (1991). Determinants and dynamics of national stereotypes. Politics and the Individual, 1, 13-26. Harris, A. C., & Verven, R. (1996). The Greek-American Acculturation Scale: Development and validity. Psychological Reports, 78, 599-610. Heras P., & Revilla, L. A. (1994). Acculturation, generational status, and family environment of Filipino Americans: A study in cultural adaptation. Family Therapy, 21, 129-138. Hoelter, J. W. (1983). The analysis of covariance structures: Goodness-of-fit indices. Sociological Methods and Research, 11, 325-344. Jayasuriya, L., Sang, D., & Fielding, A. (1992). Ethnicity, immigration and mental illness: A critical review of Australian research. Canberra: Bureau of Immigration Research. Kaplan, M. S., & Marks, J. (1990). Adverse effects of acculturation: Psychological distress among Mexican American young adults. Social Science and Medicine, 31, 13131319. Lalonde, R. N., & Cameron, J. E. (1993). An intergroup perspective on immigrant acculturation with focus on collective strategies. International Journal of Psychology, 28, 57-74. Liebkind, K. (1996). Acculturation and stress: Vietnamese refugees in Finland. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 27, 161-180. Liebkind, K. (2001). Acculturation. In R. Brown & S. Gaertner (Eds.), Blackwell handbook of social psychology: Intergroup processes (pp. 386-406). Oxford, U. K.: Blackwell. Lysgaard, S. (1955). Adjustment in a foreign society: Norwegian Fulbright grabtees visiting the United States. International Social Science Bulletin, 7, 45-51. Acculturation Attitudes 27 Maveras, V., Bebbington, P., & Der, G. (1989). The structure and validity of acculturation: Analysis of an acculturation scale. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 24, 233-240. Martens, E. P. (1999). Marokkanen in Nederland: Kerncijfers 1999. Rotterdam: Instituut voor Sociologisch-Economisch Onderzoek. Montgomery, G. T. (1992). Comfort with acculturation status among students from South Texas. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 14, 201-223. Nwadiora, E., & McAdoo, H. (1996). Acculturative stress among Amerasian refugees: Gender and racial differences. Adolescence, 31, 477-487. Olmeda, E. L. (1979). Acculturation: A psychometric perspective. American Psychologist, 34, 1061-1070. Padilla, A. M. (1986). Acculturation and stress among immigrants and later-generation individuals. In D. Frick (Ed.), Urban quality of life: Social, psychological and physical conditions (pp. 41-60). Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. Pels, T. (1998). Opvoeding in Marokkaanse gezinnen in Nederland. Assen, The Netherlands: Van Gorcum. Phalet, K, Van Lotringen, C., & Entzinger, H. (2000). Islam in de multiculturele samenleving. Utrecht: Ercomer. Phalet, K., & Swyngedouw, M. (2003). A cross-cultural analysis of immigrant and host values and acculturation orientations. In H. Vinken & P. Ester (Eds.), Comparing cultures (pp. 185-212). Leiden: Brill. Pham, T. B., & Harris, R. J. (2001). Acculturation strategies of Vietnamese Americans. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 25, 279-300. Redmond, M. V. (2000). Cultural distance as a mediating factor between stress and intercultural communication competence. International Journal of Intercultural Acculturation Attitudes 28 Relations, 24, 151-159. Sam, D. L. (1995). The psychological adjustment of young immigrants in Norway. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 35, 240-253. Shadid, W. (1979). Moroccan workers in The Netherlands. Doctoral dissertation. Leiden University, The Netherlands. Singh, A. K. (1989). Impact of acculturation on psychological stress: A study of the Oraon tribe. In D. M. Keats, D. Munroe, & L. Mann (Eds.), Heterogeneity in cross-cultural psychology (pp. 210-215). Lisse, The Netherlands: Swets & Zeitlinger. Suinn, R. M., Ahuna, C., & Khoo, G. (1992). The Suinn-Lew Asian Self-Identity Acculturation Scale: Concurrent and factorial validation. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 52, 1041-1046. Ting-Toomey, S. (1981). Ethnic identity and close friendship in Chinese-American college students. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 5, 383-406. Triandis, H. C., Kashima, Y., Shimada, E., & Villareal, M. (1986). Acculturation indices as a means of confirming cultural differences. International Journal of Psychology, 21, 43-70. Ward, C. (1999). Models and measurement of acculturation. In W. J. Lonner, D. L. Dinnel, D. K. Forgas, & S. Hays (Eds.). Merging past, present and future (pp. 221-230). Lisse, The Netherlands: Swets & Zeitlinger. Ward, C., Bochner, S., & Furnham, A. (2001). The psychology of culture shock (2nd ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Routledge. Ward, C., & Kennedy, A. (1994). Acculturation strategies, psychological adjustment and sociocultural competence during cross-cultural transitions. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 18, 329-343. Ward, C., & Kennedy, A. (1996). Before and after cross-cultural transitions: A study of New Acculturation Attitudes 29 Zealand volunteers on field assignment. In. H. Grad, A. Blanco, & J. Georgas (Eds.), Key issues in cross-cultural psychology (pp. 138-154). Lisse, The Netherlands: Swets & Zeitlinger. Ward, C., & Kennedy, A. (1999). The measurement of sociocultural adaptation. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 23, 659-677. Ward, C., Okura, Y., Kennedy, A., & Kojima, T. (1998). The U-curve on trial: A longitudinal study of psychological and sociocultural adjustment during cross-cultural transition. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 22, 277-291. Ward C., & Rana-Deuba, A. (1999). Acculturation and adaptation revisited. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 30, 372-392. Weinreich, P. (1998). From acculturation to enculturation: Intercultural, intracultural and intrapsychic mechanisms. Paper presented at the XIV International Congress of the International Association for Cross-Cultural Psychology, Bellingham, WA. Wong-Rieger, D., & Quintana, D. (1989). Comparative acculturation of Southeast Asian and Hispanic immigrants and sojourners. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 18, 345362. World Health Organization (1988). World Health Organization Cross-National Survey of Psychological and Somatic Symptoms. Geneva, Switzerland. Acculturation Attitudes Table 1. Descriptives Agea Length of Staya School Success Work Success Acculturation Attitudes (Initial Scale: all items) Attitudes toward Ethnic Culture (Factor) Attitudes toward Host Culture (Factor) Mental health * Age and Length of Stay are in years. M 21.68 S 2.29 -- 17.55 6.21 -- 3.48 .55 .85 3.67 .55 .82 3.54 .32 .87 3.87 .45 .89 3.30 .49 .89 1.77 .47 0.91 30 Acculturation Attitudes 31 Table 2. Factor Structure of Acculturation Attitudes Do you like Moroccan food? Do you like the way Moroccan food is prepared? Do you like Moroccan table manners? Do you like Moroccan home atmosphere? Do you like Moroccan home furniture? Do you like Moroccan female clothing? Do you like Moroccan male clothing? Do you like Moroccan child clothing? Do you like Moroccan physicians? Do you like Moroccan jokes? Do you like Moroccan music?a Do you like Moroccan feasts?a Do you like Moroccan sport? Do you like the Moroccan language? Do you like the size of the Moroccan family? Do you like parent-child relationship in Moroccan family? Do you like husband-wife relationship in Moroccan family? Do you like sibling relations in Moroccan family? Do you like marriage partner choice in Moroccan culture? Do you like marriage laws in Moroccan culture? Do you like domestic role distribution in Moroccan culture? Do you like friendship in Moroccan culture? Do you like girlfriend-boyfriend relationship in Moroccan culture?b Do you like stranger-stranger relationship in Moroccan culture? Do you like the Moroccan media? Do you like human rights in Moroccan culture? Do you like the rule of law in Moroccan culture? Do you like the Qurán? Do you Islamic prayer? Do you like fasting in Islam? Do you like food restrictions in Islam? Do you like time use in Islam? Do you like money use in Islam? Do you like interpersonal relations in Islam? Attitudes Attitudes toward Host toward Ethnic Culture Culture (Eigenvalue: (Eigenvalue: 8.66) 7.99) .06 .55 .04 .56 -.09 .56 .05 .67 .06 .48 -.03 .54 -.14 .44 -.03 .49 .01 .36 .26 .41 .55 .23 .46 .28 .02 .49 .16 .48 -.14 .50 .05 .45 .06 .55 .08 .44 -.11 .34 -.16 .55 -.20 .41 .04 .35 .18 .17 .07 .45 .09 .03 .05 -.07 -.06 -.07 .00 -.23 -.10 -.14 .34 .37 .32 .66 .51 .60 .50 .54 .53 .55 (Table continues) Acculturation Attitudes Table 2 (continued) Do you like Dutch food? .39 -.14 Do you like the way Dutch food is prepared? .32 -.13 Do you like Dutch table manners? .47 -.00 Do you like Dutch home atmosphere? .57 -.15 Do you like Dutch home furniture? .48 .09 Do you like Dutch female clothing? .61 -.07 Do you like Dutch male clothing? .64 .11 Do you like Dutch child clothing .58 .13 Do you like Dutch physicians? .26 .12 Do you like Dutch jokes? .53 .07 Do you like Dutch music? .47 -.15 Do you like Dutch feasts? .52 -.15 Do you like Dutch sport? .25 .19 Do you like the Dutch language? .47 .13 Do you like the size of the Dutch family? .39 -15 Do you like parent-child relationship in Dutch family? .63 -.09 Do you like husband-wife relationship in Dutch family? .62 -.08 Do you like sibling relations in Dutch family? .40 -.00 Do you like marriage partner choice in the Netherlands? .34 .01 Do you like marriage laws in the Netherlands? .66 -.01 Do you like domestic role distribution in the Netherlands? .54 .07 Do you like friendship in the Netherlands? .43 .03 Do you like girlfriend-boyfriend relationship in the .61 -.04 Netherlands? Do you like stranger-stranger relationship in the Netherlands? .39 .08 Do you like the Dutch media? .37 .03 Do you like human rights in the Netherlands? .35 .08 Do you like the rule of law in the Netherlands? .37 .17 Do you like the Bible?b .19 -.13 Do you like Christian prayer?b .18 -.06 Do you like fasting in Christianity? .38 -.16 Do you like food restrictions in Christianity? .35 -.16 Do you like time use in Christianity? .43 -.09 Do you like money use in Christianity? .50 -.08 Do you like interpersonal relations in Christianity? .49 .03 a The items point to one culture but have their highest loading on the factor dealing with the second culture. bThe items have very low communalities and therefore load on none of the factors. 32 33 Acculturation Attitudes Table 3. Major Likes and Dislikes in Ethnic Culture M S Major Likes Moroccan food The way Moroccan food is prepared Moroccan table manners Moroccan home atmosphere Moroccan home furniture Moroccan female clothing Moroccan language (respective mother-tongue) Moroccan jokes Moroccan Friendship The Qurán Islamic prayer Fasting in Islam Food restrictions in Islam Time use in Islam Money use in Islam Interpersonal relations in Islam 4.46 4.38 4.14 4.46 4.08 4.25 4.54 4.39 4.04 4.63 4.68 4.74 4.49 4.41 4.35 4.25 .82 .81 .85 .66 .95 .90 .63 .89 .97 .72 .84 .61 .73 .79 .90 1.00 Major Dislikes Domestic role distribution in Morocco Moroccan media Human rights in Morocco 2.90 2.70 2.46 1.13 1.05 .92 Acculturation Attitudes Table 4. Major Likes and Dislikes in Host Culture M S Major Likes Human rights in the Netherlands Dutch male clothing Dutch child clothing Dutch physicians 4.19 4.05 4.04 4.03 .69 .87 .90 .81 Major Dislikes Dutch food The way Dutch food is prepared Dutch home atmosphere Dutch music Dutch feasts Fasting in Christianity Food restrictions in Christianity Time use in Christianity Money use in Christianity 2.74 2.45 2.53 2.46 2.61 2.39 2.74 2.82 2.87 1.01 1.03 1.06 1.28 1.22 1.31 1.22 1.06 1.13 34 35 Acculturation Attitudes Table 5. Correlations among Background Factors, Acculturation Attitudes, and Acculturation Outcomes 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 1. Age 1. 2. Gender -.07 1. 3. Occupation .43** .08 1. 4. Education .02 .12 -.36** 1. 5. Length of stay .08 .06 .20* .01 1. 6. Attitudes toward ethnic culture -.21* -.06 -.15 -.03 -.20* 1. 7. Attitudes toward host culture -.08 .30** -.03 .03 .13 -.01 8. School success -.08 .04 -.02 -.02 .03 9. Work success .11 .12 .25* -.07 .12 10. Mental health .04 -.16 -.07 .09 .19* Coding of gender: 1 = Male, 2 = Female. *p < .05. **p < .01. 1. .20** .28** .05 .04 9 1. .26** .31** -.05 .12 1. .31** Acculturation Attitudes Figure Caption Figure 1. Scree Plot of the acculturation attitudes scale Figure 2. Hypothesised Model (Note: Correlations between background variables are not represented in the figure) Figure 3. Empirical Model. (Note: All paths are significant at p < .05 and standardized) Figure 4. Simplified Empirical Model 36 Eigenvalue Acculturation attitudes 10 8 6 4 2 0 1 5 9 13 17 21 25 29 33 37 41 45 Component Number 49 53 57 61 65 Acculturation attitudes Attitudes toward Ethnic Culture + + + + + Age + e + School Success - + + + Length of Stay + + Mental Health - Occupation + + + + + Gender + a - + + + Education Attitudes toward Host Culture Figure 2 Note: a. Gender code: 1 = Male; 2 = Female. Work Success + + + Acculturation attitudes Attitudes toward Ethnic Culture .20 -.20 -.17 Age .41 School Success Length of Stay .18 Mental Health .17 -.16 Occupation .29 .37 .22 Work Success -.20 Gendera .28 .30 Attitudes toward Host Culture Figure 3 .19 Acculturation attitudes + Time Attitudes toward Ethnic Culture - + Sociocultural Adaptation + Gender + Attitudes toward Host Culture Figure 4 + Psychological Adaptation