Hegel, The Spirit of Christianity and its Fate, section 2, excerpt

advertisement

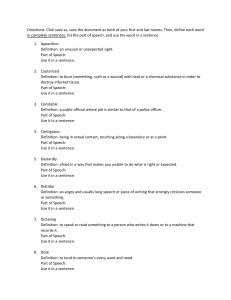

Hegel, The Spirit of Christianity and its Fate, section 2, excerpt (1799-1800)1 Against purely objective commands Jesus set something totally foreign to them, namely, the subjective in general; but he took up a different attitude to those laws which from varying points of view we call either moral or else civil commands. Since it is natural relations which these express in the form of commands, it is perverse to make them wholly or partly objective. Since laws are unifications of opposites in a concept, which thus leaves them as opposites while it exists itself in opposition to reality, it follows that the concept expresses an ought. If the concept is treated in accordance with its form, not its content, i.e., if it is treated as a concept made and grasped by men, the command is moral. If we look solely at the content, as the specific unification of specific opposites, and if therefore the “ought” [or “Thou shalt”] does not arise from the [210] property of the concept but is asserted by an external power, the command is civil. Since in the latter case the unification of opposites is not achieved by thinking, is not subjective, civil laws delimit the opposition between several living beings, while purely moral laws fix limits to opposition in one living being. Thus the former restrict the opposition of one living being to others, the latter the opposition of one side, one power, of the living being to other sides, other powers, (265) of that same living being; and to this extent one power of this being lords it over another of its powers. Purely moral commands which are incapable of becoming civil ones, i.e., those in which the opposites and the unification cannot be formally alien to one another, would be such as concern the restriction of those forces whose activity does not involve a relation to other men or is not an activity against them. If the laws are operative as purely civil commands, they are positive, and since in their matter they are at the same time moral, or since the unification of objective entities in the concept also either presupposes a nonobjective unification or else may be such, it follows that their form as civil commands would be canceled if they were made moral, i.e., if their “ought” became, not the command of an external power, but reverence for duty, the consequence of their own concept. But even those moral commands which are incapable of becoming civil may become objective if the unification (or restriction) works not as concept itself, as command, but as something alien to the restricted force, although as something still subjective. This kind of objectivity could be canceled only by the restoration of the concept itself and by the restriction of activity through that concept. We might have expected Jesus to work along these lines against the positivity of moral commands, against sheer legality, and to show that, although the legal is a universal whose entire obligatoriness lies in its universality, still, even if every ought, every command, declares itself as something alien, nevertheless as concept (universality) it is something subjective, and, as subjective, as a [211] product of a human power (i.e., of reason as the capacity for universality), it loses its objectivity, its positivity, its heteronomy, and the thing commanded is revealed as grounded in an autonomy of the human will. By this line of argument, however, positivity is only partially removed; and between the Shaman of the Tungus, (266) the European prelate who rules church and state, the Voguls, and the Puritans, on the one hand, and the man who listens to his own command of duty, on the other, the difference is not that the former make themselves slaves, while the latter is free, but that the former have their lord outside themselves, while the latter carries his lord in himself, yet at the same time is his own slave.2 For the particular – impulses, inclinations, pathological love, sensuous experience, or whatever else it is called – the universal is necessarily and always something alien and objective. There remains a residuum of indestructible positivity which finally shocks us because the content which the universal command of duty acquires, a specific duty, contains the contradiction of being restricted and universal at the same time and makes the most stubborn claims for its one-sidedness, [212] i.e., on the strength of possessing universality of form. Woe to the human relations which are not unquestionably found in the concept of duty; for this concept (since it is not merely the empty thought of universality but is to manifest itself in an action) excludes or dominates all other relations. One who wished to restore man’s humanity in its entirety could not possibly have taken a course like this, because it simply tacks on to man’s distraction of mind an obdurate conceit. To act in the spirit of the laws could not have meant for him “to act out of respect for duty and to contradict inclinations,” for both “parts of the spirit” (no other words can describe this distraction of soul), just by being thus divergent, would have been not in the spirit of the laws but against that spirit, one part because it was something exclusive and so selfrestricted, the other because it was something suppressed. This spirit of Jesus, a spirit raised above morality, is visible, directly attacking laws, in the Sermon on the Mount, which is an attempt, elaborated in numerous examples, to strip the laws of legality, of their legal form. The Sermon does not teach reverence for the laws; on the contrary, it exhibits that which fulfils the law but annuls it as law and so is something higher than obedience to law and makes law superfluous. Since the commands of duty presuppose a cleavage [between reason and inclination] and since the domination of the concept declares itself in a “thou shalt,” that which is raised above this cleavage is by contrast an “is,” a modification of life, a modification which is exclusive and therefore restricted only if looked at in reference to the object, since the exclusiveness is given only through the restrictedness of the object and only concerns the object. When Jesus expresses in terms of [213] commands what he sets against and above the laws (think not that I (267) wish to destroy the law; let your word be; I tell you not to resist, etc.; love God and your neighbor), this turn of phrase is a command in a sense quite different from that of the “shalt” of a moral imperative. 3 It is only the sequel to the fact that, when life is conceived in thought or given expression, it acquires a form alien to it, a conceptual form, while, on the other hand, the moral imperative is, as a universal, in essence a concept. And if in this way life appears in the form of something due to reflection, something said to men, then this type of expression (a type inappropriate to life): “Love God above everything and thy neighbor as thyself” was quite wrongly regarded by Kant as a “command requiring respect for a law which commands love.” And it is on this confusion of the utterly accidental kind of phraseology expressive of life with the moral imperative (which depends on the opposition between concept and reality) that there rests Kant’s profound reduction of what he calls a “command” (love God first of all and thy neighbor as thyself) to his moral imperative. And his remark that “love,” or, to take the meaning which he thinks must be given to this love, “liking to perform all duties,” “cannot be commanded” falls to the ground by its own weight, because in love all thought of duties vanishes. And so also even the honor which he bestows in another way on that expression of Jesus by regarding it as an ideal of holiness unattainable by any creature, is squandered to no purpose; for such an “ideal,” in which duties are represented as willingly done, is self-contradictory, since duties require an opposition, and an action that we like to do requires none. And he can suffer this unresolved contradiction in his ideal because he declares that rational creatures (a remarkable juxtaposition of words) can fall but cannot attain that ideal. [214] Jesus begins the Sermon on the Mount [Matthew v. 2 – 16] with a species of paradox in which his whole soul forthwith and unambiguously declares to the multitude of expectant listeners that they have to expect from him something wholly strange, a different genius, a different world. There are cries in which he enthusiastically deviates directly from the common estimate of virtue, enthusiastically proclaims a new law and light, a new region of life whose relation to the world could only be to be hated and persecuted by it. In this Kingdom of Heaven [Matthew v. 17-20], however, what he discovers to them is not that laws disappear but that they must be kept through a righteousness of a new kind, in which there is more than is in the righteousness of the sons of duty and which is more complete because it supplements the deficiency in the laws [or “fulfils” them]. (268) This supplement he goes on to exhibit in several laws. This expanded content we may call an inclination so to act as the laws may command, i.e., a unification of inclination with the law whereby the latter loses its form as law. This correspondence with inclination is the πληρωμα [fulfilment] of the law; i.e., it is an “is,” which, to use an old expression, is the “complement of possibility,” since possibility is the object as something thought, as a universal, while “is” is the synthesis of subject and object, in which subject and object have lost their opposition. Similarly, the inclination [to act as the laws may command], a virtue, is a synthesis in which the law (which, because it is universal, Kant always calls something “objective”) loses its universality and the subject its particularity; both lose their opposition, while in the Kantian conception of virtue this opposition remains, and the universal becomes the master and the particular the mastered. The correspondence of inclination with law is such that law and inclination are no longer different; and the expression “correspondence of inclination with the law” is therefore wholly unsatisfactory be [215] cause it implies that law and inclination are still particulars, still opposites. Moreover, the expression might easily be understood to mean that a support of the moral disposition, of reverence for the law, of the will’s determinacy by the law, was forthcoming from the inclination which was other than the law, and since the things in correspondence with one another would on this view be different, their correspondence would be only fortuitous, only the unity of strangers, a unity in thought only. In the “fulfilment” of both the laws and duty, their concomitant, however, the moral disposition, etc., ceases to be the universal, opposed to inclination, and inclination ceases to be particular, opposed to the law, and therefore this correspondence of law and inclination is life and, as the relation of differents to one another, love; i.e., it is an “is” which expressed as (α) concept, as law, is of necessity congruent with law, i.e., with itself, or as (ß) reality, as inclination opposed to the concept, is likewise congruent with itself, with inclination. [struck out] A command can express no more than an ought or a shall, because it is a universal, but it does not express an ‘is’; and this at once makes plain its deficiency. Against such commands Jesus set virtue, i.e., a loving disposition, which makes the content of the command superfluous and destroys its form as a command, because that form implies an opposition between a commander and something resisting the command. (Source: G.W.F. Hegel, Early Theological Writings, tr. T.M. Knox, University of Pennsylavania Press, 1975, pp. 209-216) © University of Chicago 1948 [100] = Knox pagination (100) = Nohl pagination Notes This excerpt contrasts Jesus’s approach to morality with the Kantian one, which Hegel tacitly associates with the Judaic one (all three, of course, as interpreted by Hegel). It includes the famous passage in which he says that the difference between adherents of a positive religion and the Kantian moral agent is only that ‘the former have their lord outside themselves, while the latter carries his lord in himself, yet at the same time is his own slave’. 1 2 Hegel is referring to a passage from Kant, Reason within the Limits of Religion Alone (1793), from the section 4.2.3 ‘Concerning Clericalism as a Government in the Pseudo-Service of the Good Principle’. Kant’s passage reads: ‘We can indeed recognize a tremendous difference in manner, but not in principle, between a shaman of the Tunguses and a European prelate ruling over church and state alike, or (if we wish to consider not the heads and leaders but merely the adherents of the faith, according to their own mode of representation) between the wholly sensuous Wogulite who in the morning places the paw of a bearskin upon his head with the short prayer, “Strike me not dead!” and the sublimated Puritan and Independent in Connecticut: for, as regards principle, they both belong to one and the same class, namely, the class of those who let their worship of God consist in what in itself can never make man better (in faith in certain statutory dogmas or celebration of certain arbitrary observances).’ Hegel is extending the accusation of clericalism to Kant. The idea that Jesus’s ‘commands’ do not have the same meaning as those of Judaism and Kant anticipates both his later idea of Sittlichkeit and that of a speculative sentence. 3 Andrew Chitty 30 January 2006