Syllabus - Kansas State University

advertisement

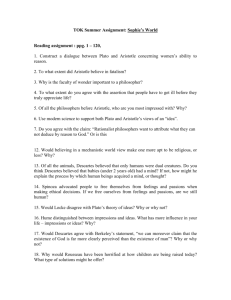

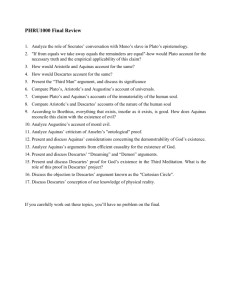

1 English 297 Ref. #11720 Freshman Honors Intro to Humanities TU 9:30-10:45 EH 227 Prof. M. L. Donnelly Office: EH 23C Office hours: TU 8:30-9:20 & 11:00-11:20 AM, TU 2:00-3:00 PM; and by appointment. Scope: A discussion-survey of some seminal works in the Western literary, philosophical, and cultural tradition; enrollment generally limited to entering honors freshmen. This class forms part of the Freshman Honors Humanities Program, along with HIST 297, MLANG 297, and PHILO 297. All classes in the Freshman Honors Humanities Program have a common reading list and will follow approximately the same course format, but details of the schedule and assignments differ from course to course. This syllabus is meant to apply only to ENGL 297. In this section, we will pay particularly close attention to the ways language functions in representing and shaping the individual’s values and relations to the divine, to nature, to society or culture, and to other individuals. PLEASE NOTE that at four times during the semester the entire Freshman Honors Humanities Program will meet together. Since these evening meetings may cause conflicts, but are a required portion of the course, you should note these dates and reserve them for this class now. Evening Session I—September 17 Evening Session II—October 15 Evening Session III—November 12 Evening Session IV—December 10 All four evening sessions will be held in the Hale Library Hemisphere Room (5th floor), 7:00-9:20 PM. Required Texts: Homer, The Iliad, trans. Robert Fagles (Penguin Books). Thucydides, On Justice, Power, and Human Nature (selections from History of Peloponnesian War), trans. P. Woodruff (Hackett). the Plato, The Republic, 2nd ed., trans. G. M. A. Grube, rev. by C. D. C. Reeve (Hackett). Niccolo Machiavelli, The Prince, trans. Luigi Ricci, rev. E. R. P. Vincent (Viking/Penguin). William Shakespeare, Antony and Cleopatra, ed. Maynard Mack (Penguin Books). Rene Descartes, Discourse on Method and Meditations on First Philosophy (Hackett). Goethe, Faust, trans. Walter Kaufmann (Doubleday-Anchor). Mary Shelley, Frankenstein (Penguin Books). Karl Marx and Frederick Engels, The Communist Manifesto (International Publishers). 2 The Darwin Reader, 2nd ed., ed. Mark Ridley (Norton). Count LeoTolstoy, The Death of Ivan Ilyich and Other Stories, trans. Aylmer Maude (Signet Classic/NAL Penguin, Inc.). Sigmund Freud, Civilization and Its Discontents, trans. J. Strachey (Norton). Chinua Achebe, Things Fall Apart (Bantam Doubleday Dell Anchor Books). ALSO REQUIRED: “Honors Introduction to the Humanities”, a collection of photocopied readings from Heloise and Abelard, Historia calamitatum and Personal Letters, available at Claflin Books. Course Requirements: 1) First paper, 4-6 pages, typed double-spaced, due Wednesday, September 17 at evening meeting (ca. 15% of course grade). Topics to be distributed by Tuesday, September 9. (Explication de texte—close reading of a particular passage and its function in the text; more information Sept. 4 or 9.) (2) Second paper, 4-6 pages, typed double-spaced, due Wednesday, October 15 at evening meeting (ca. 20% of course grade). Topic—usually a comparison or discussion on thematic or formal grounds—may be chosen by you and cleared with me by Tuesday, September 30 at the latest; suggested topics to be announced by September 23. (3) Term paper, 6-9 pages, typed double-spaced, due Wednesday, December 10 at evening session (ca. 30% of course grade); you are responsible for generating your own topic involving a broad overview of issues suggested by texts in the course; your choice of topic to be cleared with me by Thursday, November 20 at latest (examples of the sort of thing you might undertake will be given November 12). TAKE-HOME FINAL—questions will be handed out at group evening session December 10; due Thursday, December 18, by 4:00 PM in Denison 106; whole set of three short papers (2-4 pp. each) worth about 25% of course grade. All papers to be typed, or printed by word processor. Double space papers, leaving one inch margins for comment and question; cite references for quotations and ideas taken from either the texts for the course or any other books or articles you might consult (or any other borrowed ideas or observations, as: “Observation of J. Blow, my roommate; private communication, September 20, 2003.”). But the point of these exercises is that they are to represent primarily your own best efforts in thinking about and organizing your ideas and analysis of the topics, so do not rely heavily on secondary sources or readings other than the assigned texts. The remaining 10% of the course grade is based on class participation-participation, not merely "attendance." Having read the assigned text before coming to class is a basic prerequisite for participation. NOTE ESPECIALLY THE FOLLOWING STATEMENTS, INCLUDED IN THIS SYLLABUS PER RECOMMENDATION OF JANE D. ROWLETT, DIRECTOR OF UNCLASSIFIED AFFAIRS AND UNIVERSITY COMPLIANCE: University Honor System: 3 Kansas State University has an Undergraduate Honor System based on personal integrity which is presumed to be sufficient assurance that in academic matters one's work is performed honestly and without unauthorized assistance. Undergraduate students, by registration, acknowledge the jurisdiction of the Undergraduate Honor System. The policies and procedures of the Undergraduate Honor System apply to all full and part-time students enrolled in undergraduate courses on-campus, offcampus, and via distance learning. A prominent part of the Honor System is the inclusion of the Honor Pledge which applies to all assignments, examinations, or other course work undertaken by undergraduate students. The Honor Pledge is implied, whether or not it is stated: "On my honor, as a student, I have neither given nor received unauthorized aid on this academic work." A grade of XF can result from a breach of academic honesty. An XF would be failure of the course with the X on the transcript indicating failure as a result of a breach of academic honesty. For more information, please visit the Honor System web page at: http://www.ksu.edu/honor. Academic Accommodations for Students with Disabilities: Any student with a disability who needs an accommodation or other assistance in this course should make an appointment to speak with me as soon as possible. Notice of copyright for course syllabi and lectures: Copyright 2003, M. L. Donnelly as to this syllabus and all lectures. During this course students are prohibited from selling notes to or being paid for taking notes by any person or commercial firm without the express written permission of the professor teaching this course. I would be happy to discuss your papers with you outside of class, and to review drafts and make comments on them as time permits. In any case, I expect to schedule at least one and preferably more individual conferences with each of you during the semester. Your grade for the course will be based primarily upon your written work. However, the essence of the humanities is discourse articulating, appreciating, testing, and comparing values. Consequently, these courses are intended to proceed chiefly through class discussion, and your attendance and active participation in class discussion will have a 4 significant bearing on your final grade (c. 10%). Active participation means more than simply being there, occupying a seat. It means demonstrably engaging the issues discussed in class, raising questions, making comments and connections, testing your own and others’ interpretations and reactions. Intelligent questions about specific points in the text and the ability to suggest passages that shed light on issues under discussion are excellent ways of showing that you have read the material and are trying to come to grips with it. There will be a 297 LISTSERVE again this semester; everyone enrolled in the course is required to be a participant. If you are shy about speaking out in class, the LISTSERVE can be an excellent medium through which you can enhance your own level of participation in the thought and discussion of the course, test others’ reactions to your reflections and analysis, and responsibly help others clarify, refine, and fill out their own thoughts and reflections on the meaning of the texts we read, and the issues raised in our readings. I will collect your e-mail addresses at the first meeting. If you do not yet know your e-mail address at that time, let me know it as soon as possible within the first two weeks of class. I will also make it a practice to ask you, at the end of each class period, to write down and hand in to me (1) the most important thing you learned from that day's discussion, and (2) the most important question remaining in your mind after the discussion. I will write answers to these and hand them back at the beginning of the next class, and we will take up questions of particular importance, or questions that several people have raised, during the next class period. Class schedule: This outline is not chiseled in stone; it represents a sketchy and doubtless implausibly optimistic plan of what we shall be doing and when we should be doing it. Paper due dates are inflexible, but otherwise expect discussion to expand or contract according to the class’s interest and needs (but not contract much). If you fail to attend class, you may have a hard time figuring out where we are—and that is not getting your money’s worth (besides, you would be neglecting your duty to share your ideas and insights with others, and to learn from their perspectives). Separate sheets may be handed out from time to time suggesting topics to think about for class discussion. And, again: this is a discussion course: do come prepared with questions and reflections on the texts assigned, and do participate. Other sections of the course: HIST 297 MWF 9:30 EH201 MLANG 297 MWF 1:30 DE222 PHILO 297 TU 3:30-4:45 D 106 First Week (Week of August 18) 21 August: Introduction to the course, and to the idea and approaches of the humanities. Read for second meeting: The Iliad, Books I complete, II, ll. 1-397, III complete, Book IV, lines 1-80, 489-end; skim Book V complete, read carefully Book VI, lines 137-end. Pay particular attention to repetition and formulaic language—are they functional and artistic, or just an accident of the mode of composition (which we’ll discuss)? Note what forms and/or personal qualities seem to constitute authority or to privilege appeals or claims of one man upon another; reflect on the poem’s attitude toward warfare, competition, and cooperation; begin to reflect on the nature and components of “the 5 heroic ethos.” What are the essential values of this culture? what, for it, constitutes the highest virtue? what are its highest goods? Other issues you might think about: Peculiar qualities of Homer’s literary art: how do his similes work? what are they doing in the poem and to the reader? observe instances of concreteness, particularity, “presence,” lack of hierarchy in what is attended to or valued; consider Homer’s partisanship or lack of it, and what factors contribute to our sense of this quality or its absence. ________________ Second Week: 26 August: Discussion of assignment in Iliad. Read for next meeting Iliad, Book IX (this will be the central text for our discussion); skim X quickly, skim XI until line 706, read carefully 706 to end of XI; XII, beginning-385. Read on about the deception of Zeus by Hera, XIV, lines 187-429, and study closely Book XVI, the Patrocleia. 28 August: Reflect on the role of the gods and the nature of the divine in the poem; consider human responsibility, particularly Achilles’s. Some critics argue that Achilles’s response to the ambassage of Ajax, Odysseus, and Phoenix in Book IX makes the poem a tragedy and Achilles a responsible moral agent. Why might they say this about this episode? why would it not have been true before, within the limits of the heroic ethos? Reflect further on the heroic ethos and the values that matter to this culture. Reflect on Odysseus as heroic figure compared to what you have seen of Diomedes, Ajax, Agamemnon, and Achilles. Assertions of titanic individualism and egoism are easily found in the poem, but think also about the social, communal checks on unbridled egoistic self-assertion. Read for Tuesday Iliad, Book XVIII; skim XIX, attending especially to lines 1-281; XXI; XXIII, esp. 1-726; study closely XXII and XXIV. Think about the following: What is the function of the 180-odd lines at the end of Book XVIII describing the decoration of the arms Hephaestus forges for Achilles (ekphrasis)? Look for symmetry in the presentation of the public resolution of the quarrel between Achilles and Agamemnon in XIX, balancing its initiation in Book I, and Agamemnon’s peace offering in IX. What purpose do the hyperbolically heightened events of XXI serve in the economy of the poem? Reflect on the presentation of the “psychology” of Hektor and the choices he makes in XXII; is he finally a sympathetic figure in the poem? The Iliad has been called “the poem of force,” and its announced subject is “the wrath [menis] of Achilles,” which results in strife [eris] and pain [algea] for the Achaeans. Evaluate the conclusion in Book XXIV in terms of its relation to these dominant themes. Does the ending seem appropriate, or unexpected (hence, unprepared-for)? Is it artistic? What is the effect achieved? Does the poem seem to resolve itself dominated by the tragic tone discussed earlier? What does it say about the human condition? Begin reading in Thucydides: read Introduction (pp. ix-xxxiii) and chapters 1, 2, & 3 (pp. 1-58). Compare Thucydides and Homer as writers—what interests them or occupies their attention? How do they present their material? Try to discern something about form and structure in Thucydides. Look for thematic issues that may or may not represent continuities with the heroic ethos; reflect on the place of virtue, intelligence, and fortune in Thucydides’ narrative; consider the comparative weight given to the individual and the community, the polis. 6 ____________ Third Week: 2 September: Last discussions of Iliad. Begin discussion of Peloponnesian War. For next Thursday, read chs. 4-8. Reflect on how Thucydides presents appeals to values and appeals to expediency and power in the speeches he gives his historical figures. Is the account of the Syracusan campaign “objective history,” or is it presented tendentiously? What “lessons” do you discern in Thucydides? What is the role of the Melian Dialogue in the economy of the book? 4 September: finish Thucydides. For next Thursday, read Plato, The Republic, Book I, Book II.357-67 and Book II.368-Book IV.445b. Reflect on the reason for introducing an anatomy of the ideal polis as a technique for getting at the definition of “justice.” Is the argument concerning differing natures in men and the natural division of labor sound and true? (What kind of assumptions about the fundamental true “nature” of a thing or person lie behind this proposition?) Consider the role of censorship; the role and nature of education. Happiness [eudaimonia] as an end; relation of the other cardinal virtues (bravery, temperance or moderation, and wisdom) to justice. Reflect on the relation of the product of Plato’s dialogue and analysis to the conventional notions conveyed by the words he discusses. Why does he use the dialogue form? What advantages does it possess? what are the liabilities? [Distribute topics for first paper?] ______________ Fourth Week: 9 September: Discussion of topics for Paper #1. Discussion of assigned readings, concentrating on The Republic II.368-IV.445b. For next Tuesday, read Book V.471c-480, Book VI. 502c-VII.521b. If there is time, we’ll go on to look at Book VIII.543aIX.592b. Certainly look at Book IX, and at X [595a-608b], which returns to Plato’s quarrel with the poets, and concludes with . . . (see assignment for next time)-11 September: (cont. from last session) . . . another famous Platonic myth concerning the soul’s immortality. You might want to think about some of the following: evaluate the idea of the “philosopher-king;” what it is to be a philosopher in Plato’s sense; the relation of Truth to the realm of the sensible; Plato’s elitism. Reflect on Plato’s use of similes in his argument: e.g. the simile of the sun (VI.507a-509c), the divided line (509d-511e), and the Cave (VII.514a-517c). Books VIII and IX further clarify the nature and preeminence of The Good, and its relation to Happiness, by analyzing the four other types of city and of men deviating from the standard established by Plato’s Republic. Book X is the locus classicus for the philosopher’s articulation of the conflict between the poets and philosophers, which (perhaps under the guise of rhetorician vs. philosopher or sophist vs. philosopher) can be seen as one of the fundamental conflicts in the history of the European Mind (the fundamental clash?). What is at stake? How does it relate to Plato’s epistemology and fundamental conception of reality? How would you answer Plato? You might want to survey several of the Greek texts we have read (or all of them) as they bear on some question of action, conduct, or values; or triangulate between their values and those of our era on some problem or issue. [Anyone want to review Karl Popper, The Open Society and Its Enemies, as a lever against Plato?] 7 _______________ Fifth Week: 16 September : Finish discussion of Plato’s Republic. Our class will lead the first group session in Leasure 013 Wednesday evening. We may want to use some of the class time to firm up plans for how to conduct that session. For next Tuesday, read the selection of the Historia calamitatem by Abelard and the letters between Abelard and Heloise in the photocopied text from Claflin Books. Reflect on how these voices are like or unlike the voices we have heard in the texts from classical antiquity. Do you feel that tradition and authority or hierarchy are more important as standards of judgment and guides to thought and action than they were, in general, in the Greek texts we read? Do you feel a greater articulation of subjectivity in Heloise’s than in Abelard’s correspondence? Is the Abelard of the Historia the same as the Abelard of the letters? Reflect on eudaemonia vs. duty and obligation—to God, to the Church, to one’s religious order, to Truth. (Have you found this conflict so sharply outlined in our earlier readings?) What is the significance of citation of earlier texts in these two texts (“intertextuality”)? Are earlier texts a standing quarry to be plundered for building blocks, like the Roman Colosseum in the Middle Ages, a mass of clues and pieces hinting at a gigantic puzzle to be assembled and solved, a collection of non-essential ornaments and flourishes, an assemblage of truth-claims to be examined and interrogated, or what? 17 September: FIRST PAPER DUE at Evening session reviewing texts from the Classical World: Hale Library Hemisphere Room, 7:00 PM-9:20 PM. 18 September: No class scheduled. _______________ Sixth Week: 23 September: Discussion of Historia calamitatem and “Personal Letters” of Heloise and Abelard. For Thursday, read in Machiavelli’s The Prince, the Letter of Dedication to Lorenzo the Magnificent, and chapters 1-3, 5-9, 15-17. Think about Machiavelli’s presentation of the acquisition and use of power as a conscious work of art. Keywords: virtù, fortuna, occasione, and necessitá. Purpose of the book; emphasis on knowledge and experience; why does Machiavelli so often couple an example from ancient history with one from recent Italian events? What is his view of the use of history? Method: Regola generale, universal rules, and imitation of great models. What is M’s view of human nature? Study and reflect on the example of Cesare Borgia’s career in Chapter 7. How is Borgia’s career different from that of Agathocles of Syracuse (Chapter 8), in order to justify M’s differing evaluations of them? Machiavelli’s work as literary, “artful” manipulation of metaphor, theme, poetic justice—as mythopoesis. Suggested topics for Paper #2 circulated. 25 September: Discussion of Machiavelli and the use of reason and authority in the renaissance. The value of words as representations of self and the world; vitality of language (preparation for Antony & Cleopatra). For next time, Machiavelli, Chapters 1819, 22-26, and start to read Shakespeare, Antony and Cleopatra. ___________ Seventh Week: 8 30 September: Wrap up discussion of Machiavelli; segue to Shakespeare's Roman history. For next time, think about the creation of two worlds in Antony & Cleopatra and the delineation of the values, attitudes, ethos of each. Is it fair to characterize one as sensual, exotic, “Eastern” or “Oriental,” the other rational, pragmatic, and “Western”? One feminine, the other masculine? A “private world” vs. a “public” one? Is one morally preferable to the other? Finish reading A & C over the weekend. Topic for Paper #2 to be cleared with me by today. 2 October: Discussion of Antony & Cleopatra. For next time: Eudaemonia again? What is the function in the play of that noblest of classical [masculine] virtues, amicitia, friendship—and loyalty [Enobarbus and Antony’s veterans]? How do you respond to the bogus “Egyptian bacchanals” in II.vii.? Especially Menas’s offer to Pompey? What do you make of the fact that the climactic battle of Actium comes so early as III.x. with comparatively little (?) dramatic emphasis, and Cleopatra has the whole last act to herself, after Antony’s death? Think about Shakespeare’s dramatic economy in this disposition of emphases (what would Octavius Caesar say?!). Go over the death scenes of Antony and of Cleopatra; reflect on the imagery, the metaphors and hyperbole the poet gives his characters and uses to characterize them; even the names of their servants [a standard Renaissance iconographic motiv has Cupid (Eros) disarming Mars for erotic dalliance with Venus: it was conventionally interpreted moralistically as emblematizing the unmanning of the courageous, active, public man by the effeminate blandishments of lust—and in the Renaissance, “effeminate” was the term applied to a man given over to erotic desires.] Suicide was an acceptable Stoic act when confronted with a fortune that left no scope for human dignity or great-souled transcendance—but are the deaths of Antony and Cleopatra Stoic martyrdoms? And how do you think Shakespeare’s Renaissance Christian audience could have been expected to respond to these pagan politiques and sensualists? _____________ Eighth Week: 7 October: Discussion of remainder of A&C. For next session, read Descartes’ Discourse on Method, the text we shall examine after A&C. Concentrate for discussion next time on Parts One through Four (to supplement your reflections on Descartes, you may want to read ahead in Meditations on First Philosophy, Meditations One through Three, which go over this same ground.) For next time: Be prepared to talk about the use of skepticism by Descartes; the importance he gives to “method”; and the role of his proof of the existence of God in his project. Compare how Descartes’ method of “doing philosophy” (or at least how the way he presents his doing of philosophy) differs from Plato’s (look particularly at the first Book of The Republic and the Second Part of the Discourse). Can you find in the machinery of Descartes' thought relics of the scholasticism Descartes would explode? Examine Descartes’ style: Stanley Fish has characterized certain seventeenth-century English styles as “self-consuming artefacts,” styles that turn in upon themselves, qualify, redirect the movement of thought through piled up concessions, qualifications, and subordinate clauses, until they virtually deconstruct themselves. Can you apply this analysis to Descartes’ style? or is he wholly arrogant and self-confident in his pronouncements? 9 9 October: Discussion of Descartes, Discourse One through Four with supplementary reflections on Meditations One through Three. For next time, read the rest of the Discourse, and think about the relation of Descartes’ project to the Baconian and Galilean enterprise of experimental science. Note Descartes’ characterization of animals and the animal “soul” in Part Five of the Discourse, and reflect on implications of this position. Note especially the prefatory matter in the Meditations—the Letter of Dedication and the Preface to the Reader. Reflect on Descartes and censorship, and Early Modern problems of the author's "authority" as it relates to Authority over writing. Note his explanation of why he writes the Discourse in French, not Latin. Descartes is famous for posing for the Modern World the terms of the “mind-body problem.” What does this mean, do you think, and how do these works contribute to the Problem? For next week, start reading Goethe, Faust, Part 1. __________________ Ninth Week: 14 October: No class: Fall Break Holiday. 15 October: Second Evening Class, Hale Hemisphere Room, 7:00-9:20 PM; overview of texts representing the Middle Ages, Renaissance, Reformation, and Enlightenment. Second Paper due at evening class session. 16 October: No class scheduled, unless further discussion of Descartes is required. For next week, prepare to discuss Goethe, Faust, pp. 1-95. What is the function of the prefatory matter—Dedication, Prelude in the Theatre, Prologue in Heaven? Is this a text for reading or a play for acting? What kind of God does Goethe depict? what kind of devil? Goethe’s alterations of the traditional Faust-story: what does this Faust really want? what kind of man is he? what is his relation to Nature? (what does Goethe’s “Natur” mean?); the “character” of Mephistopheles. Wagner as foil. Faust, Wagner, and the burghers and peasants: what is this scene for? Reflect on lines 1064-1144, esp. 11001144. __________________ Tenth Week: 21 October: [Finish discussion of Descartes?] Discussion of Goethe's Faust. For next session, read Goethe, Faust, pp. 207-end. Study carefully the scene, “Forest and Cavern.” Is Goethe’s effect in the scene, “Cathedral,” like that in his account of the folk customs tormenting and ostracizing the “fallen woman”, a criticism of life, or just pathos? Is the satire in the Walpurgisnacht episode integrated into the play, or not? Scholars tell us that “Gloomy D ay—Field” is the oldest layer of the text of Faust as we have it. Can you do anything with this fact? Is it significant that this scene is introduced at this precise point? (reconsider again the order of scenes and events in the whole Margaret or Gretchen episode) Gretchen is responsible legally for the deaths of her mother and baby, and is seen by her neighbors as morally responsible for the death of her brother, yet Goethe’s Heaven saves her at the end. Why? 23 October: Discussion of Faust. For next week, read Mary Shelley, Frankenstein, (pp. 13-112 for Tuesday, pp. 113-215 for Thursday). ________________ 10 Eleventh week: 28 October: Finish discussion of the end of Faust, Part II. Discussion of Frankenstein. What difference (if any) would it make to have read the “Preface” signed “Marlow” but actually by Mary Shelley’s husband, the Romantic poet and radical reformer, Percy Bysshe Shelley, in 1818, rather than Mary Shelley’s own “Introduction” to the 1831 Standard Novels edition? Why do you suppose Shelley wrote that “Preface” for his wife? What is the function of the Robert Walton frame for Frankenstein’s story? Have you ever read any other stories that work with a framed narrative like this? Speculate about ways that it may work. Is this original version of the story essentially the same as the popular versions you may know from movies and cartoons? What differences do you notice? Pay particular attention to Victor Frankenstein’s articulation of the values he subscribed to in his dedication to experimental science (chapters 3 and 4; but note particularly the language and tone used in pp. 53-55). Is the presentation of “science” in the rest of the fiction always consistent with this chapter? Is this chapter consistent with itself? Articulate as many different versions of the ethos of science as you can uncover encoded in this text. [Baconian, exoteric, humble, cooperative, rational, slowly accumulative addition of truth to truth, or esoteric, secret, lonely pursuit of magical and stupendous power by genius essentially set apart from the rest of humankind—the “mad scientist” of science fiction?] For next session, finish the novel. Think about possible symbolic or even allegorical interpretations of the plot and characters; reflect on the connections of the characters, themes, and atmosphere of this book with some of the dominant traits of European Romanticism [consult a reference like Joseph Shipley, A Dictionary of World Literature, or C. Hugh Holman, A Handbook to Literature, or an encyclopedia of philosophy or history of ideas in the library if you’re not sure what “Romanticism” as a historical movement means]. 30 October: Frankenstein, concluded. For next session, read Marx and Engels, The Communist Manifesto. Reflect on the language, tone, and attitude expressed in Engels’s “Preface” to the English edition of 1888. Marx’s language and analysis: make a list of what you think are key terms and concepts in this text. How does Marx view history? What is the nature of humanity and human society in Marx’s view (human nature is essentially good, but society corrupts? human nature is essentially evil, and society redeems or controls? human nature fixed and unchanging, or not? social control a necessary evil, or a force for reform and for good?) What is most fundamental in Marx’s thought? What is the most revolutionary concept you find in this text? What does Marx think is his most significant contribution? Also consider the following: Why does Marx spend so much time denouncing and refuting heretical leftist docrines in Part III? Try to establish continuities with other texts we have read. Marx has been called by Erich Fromm “a humanist, for whom man’s freedom, dignity, and activity were the basic premises of the ‘good society.’” Can you substantiate or support this view from the Manifesto (another opportunity to consider the questions, what is The Good for Man? what is the Good Life?)? ___________________ Twelfth Week: 4 November: Discussion of The Communist Manifesto. Start reading in The Darwin Reader, pp. 52-111. Consider the logic of argumentation and rhetoric of exposition in 11 Darwin. How does Darwin work from particular cases to general conclusions or deduced laws, compared to Machiavelli's movement from historical examples to regola generale? How does Darwin's process of reasoning in natural science compare to Marx and Engels' in constructing a "theory of historical progress"? [More questions on Darwin will be posted on the course Bulletin Board or the Listserv.] 6 November: Finish discussion of The Communist Manifesto. Begin discussion of Darwin's writings--issues in the assigned pages. For next time, read in Darwin Reader, pp. 111-135, 175-204. __________________ Thirteenth Week: 11 November: Darwin: discussion of issues in the assigned reading. 12 November: Third Evening Class, Hale Hemisphere Room, 7:00-9:20 PM; Romanticism and the Enlightenment Project continued; Grand Theory in the Nineteenth Century. Examples of paper topics for Term paper distributed. 13 November: No class scheduled. Start reading Tolstoi, The Death of Ivan Ilyich, for Thursday. Problems of technique: consider the point of view from which this story is presented. Why use third person limited center of consciousness, keeping you largely restricted to Ivan Ilyich’s perceptions and thoughts, instead of simply going to first person narration, or a consistently external ominiscient narrator? Why does Tolstoi start with Peter Ivanovich? Look for instances of intrusion of authorial judgment and evaluate the calculated effect. Does it matter to our response to Ivan that we know authoritatively what his wife and daughter think at various times? What is the significance of Gerasim? Pacing of the story: note how Tolstoi manipulates narrative time, quickly covering years of events in brief summary ("narrative treatment"), then drawing out the direct presentation of certain scenes and incidents ("scenic treatment"). What is the purpose of this manipulation of time and density of presented detail? _________________ Fourteenth Week: 18 November: Begin discussion of Death of Ivan Ilyich. Finish reading Ivan Ilyich for Thursday. How does Tolstoy present society in this story: is the machinery for attaining The Good social? is it simply individual self-gratification or “self-fulfilment”? “What must I do to be saved?” according to Tolstoy? 20 November: CLEAR FINAL PAPER TOPIC WITH ME BY TODAY. Finish discussion of The Death of Ivan Ilyich. For next session, Tuesday before Thanksgiving break, read Freud, Civilization and Its Discontents. Is Freud a rationalist? Could you call him (as Phillip Rieff does in a book title, a "moralist"? Is he a liberal, or “liberating” thinker (think about what this label ought to mean, considering its etymology, before you go off on a tangent--could you put him in any justifiable way in the same category with J. S. Mill). Is he a realist? Or would you characterize him as a pessimist? Consider this book, the product of the late ruminations of one of the genuine transformers of culture and thought, an immensely and widely cultivated central European intellect at the end of a distinguished and productive career, but reflecting on civilization in the shadow of the Great War and the rise of fascism; what is your reaction to the prospects this text projects 12 or implies for the future of the dialogue your have followed so far, and the civilization that dialogue reflects, influences, and criticises? Over the Holiday, bring the ideas and the methods of Marx, Darwin, and Freud into dialogue in your mind in preparing for our final Wednesday evening meeting the second week after we return from break. ____________________________________________________________ THANKSGIVING HOLIDAY, 26-30 NOVEMBER ____________________________________________________________ Fifteenth Week: 2 December: Discussion of Freud’s Civilization and Its Discontents. Attend particularly to Freud's remarks concerning women and their role in culture. Are Marx, Darwin, and Freud fulfilling the Enlightenment project, or subverting it? What do we need to sustain us in this world? Get a head start reading Achebe’s Things Fall Apart for next week). 4 December: Marx, Darwin, Freud, and the cumulative weight of the European adventure in thought up to the twentieth century. For next week, finish Achebe. ________________ Sixteenth Week: 9 December: Discussion of questions raised by Achebe’s Things Fall Apart in terms of themes of the course, complicated by the setting of the story in a non-European culture— individual responsibility and will, education and socialization, the individual conscience and authority (of the culture, or tradition, in this case), concentration on means and concentration on ends; considerations of universals vs. social constructionist or relativist perspectives. Is Achebe’s book formally clearly something outside the Western Tradition as we have seen it? Or does it incorporate Western forms and practices with elements native to Achebe’s Nigerian roots? Are the issues of moral action, desire, ambition, “the good life” as they emerge in this book intelligible in terms of Plato’s analysis, or Machiavelli’s, or Mill’s or Freud’s, or are wholly foreign criteria called for? 10 December: Evening meeting at 7:00-9:20 PM, Hale Hemisphere Room, for final group discussion with all classes of 297. Achebe’s book and its place in the “great conversation.” Overview. TAKE-HOME FINAL EXAM QUESTIONS HANDED OUT AT THIS SESSION. 11 December: NO REGULAR CLASS MEETING (I will be available in the classroom to discuss the latest readings or larger overviews of the texts and issues of the course with anyone who wishes to confer.) ____________________ TAKE-HOME FINAL EXAMINATION HANDED OUT IN CLASS WEDNESDAY, DEC. 10, DUE IN ENGLISH DEPARTMENT OFFICE, DE 106 BY 4:00 PM, THURSDAY, DECEMBER 18.