1

Abu Ghraib Prison

Formal ISU Research Paper

Due Date: June 1, 2010

Course Code: CLN 4U1

Teacher: Mr. O’Reilly

2

Introduction:

“They will be handled not as prisoners of war, because they’re not, but as

unlawful combatants. As I understand it technically, unlawful combatants do not have

any rights under the Geneva Convention” – United States Defence Secretary Donald

Rumsfeld.i On March 20, 2003 the United States invaded the country of Iraq and a mere

three weeks later toppled the Hussein regime.ii As the U.S. proceeded to take over, the

rest of the world was cut off from Iraq, leaving many nations wondering what the United

States was hiding. It was only a year later when 279 images and 19 videos were released

in 2004 depicting American soldiers viciously abusing and humiliating Iraqi prisoners at

Abu Ghraib Prison. The photographs caused an outrage around the world, and many

organizations demanded answers and justice.

History of Abu Ghraib Prison:

Abu Ghraib Prison is located in Abu Ghraib, an Iraqi city 32km west of

Baghdad.iii It was built by British contractors in the 1960s and covers 280 acres of land

with a total of 24 guard towers.iv The area of the prison was divided up into five separate

walled compounds for different types of prisoners.v The five compounds were designed

for foreign prisoners, long sentences, short sentences, capital crimes, and “special”

crimes.vi The prisoners were kept in row-upon-row of one or two storey cellblocks

comprised of a dining room, prayer room, exercise area, and basic washing facilities.vii

The only decoration found in the drab prison cells were bizarre portraits of Saddam

Hussein and inscriptions of his “words of wisdom.”viii During Hussein’s reign Abu

Ghraib held as many as 15,000 people making the prison unbearably overcrowded with

up to 40 people in each cell.ix The prison quickly became known as a place where

3

Hussein’s government tortured and executed dissidents.x Amnesty International reports

give some idea of the scale of brutality that occurred at Abu Ghraib during Saddam

Hussein’s reign such as, the mass execution in 2001 of political prisoners.xi In addition to

executions, detainees were subjected to extreme torture including the use of electric

shocks, drills and lighted cigarettes used on the bodies of prisoners, extraction of

fingernails, beatings, mock executions, and threats to rape detainees’ relatives.xii Local

resident Yehiye Ahmed recalled the constant sound of prisoners’ screams over the prison

walls and even witnessed atrocities when he entered the compound to sell sandwiches

and cigarettes.xiii “I saw three guards beat a man to death with sticks and cables. When

they got tired, the guards would switch with other guards. I could only watch for a minute

without getting caught, but I heard the screams, and it went on for an hour.”xiv

As Saddam Hussein’s regime struggled by in 2002, Hussein declared a general

amnesty and all prisoners were released from Abu Ghraib.xv Not too long after, the

regime collapsed at the hands of the United States in April of 2003, leaving Abu Ghraib

deserted.xvi Easily accessible to pillagers, the prison was stripped of everything that

could be removed, including doors, windows, and bricks.xvii

On April 22, 2003, the U.S. Military Police took over Abu Ghraib Prison,

securing the location for their own purpose as a possible center for operations.xviii In the

months that followed, Abu Ghraib Prison was redesigned; floors were tiled, cells cleaned

and repaired, and toilets, showers, and a new medical center added.xix The Hard Site, the

American’s name for the old cellblock complex was also refurbished to the U.S.

military’s specifications; however it was not until later that its true purpose became

known.

4

Conflict:

On January 13, 2004, Specialist Joseph M. Darby, an M.P. received a CD from

Charles Graner, a member of the 372nd Military Police Company positioned at Abu

Ghraib.xx Upon looking at the CD, Darby came across several pictures of naked

detainees from the prison and immediately gave it to his superiors in the Army’s Criminal

Investigation Command.xxi The following day, the Army launched a criminal

investigation at Abu Ghraib Prison, placing Major General Antonio M. Taguba in

charge.xxii 279 photographs and 19 videos were recorded from the CD officer Graner sent

covering a three month period of detainee abuse.xxiii

Many of the problems eventually revealed at Abu Ghraib were uncovered in an

evaluation by Major General Donald Ryder.xxiv While visiting the detention center,

Ryder’s team found that human rights, health, sanitation, and security conditions were

not being sufficiently met.xxv Most military units within the prison were under-staffed

and lacked resources and basic necessities.xxvi Ryder’s team found major sanitation

problems at Abu Ghraib, including trash-strewn compounds, and flimsy tents that

provided little protection from the weather and enemy attacks.xxvii In his review, Ryder

concluded that future detention operations at the prison were not sustainable, and would

not be conducive with the long term management of detainees.xxviii His team also

revealed that the military units located at the prison did not receive the correct amount of

training to govern a prison effectively.xxix In addition to the poorly managed prison,

investigators found that multiple human rights abuses had occurred at Abu Ghraib Prison

conducted by military personnel. More than ten U.S. soldiers, mainly from the 372nd

Military Police Company, and Iraqi civilian contractors were involved in the abuse of

5

more than 20 detainees.xxx Interrogation techniques similar to those used at Guantanamo

Bay were inflicted upon the prisoners, frequently involving nudity, stress positions, and

hooding and sleep deprivation.xxxi Major General Taguba reported some of the atrocities

committed at Abu Ghraib Prison’s Hard Site, such as: breaking chemical lights and

pouring phosphoric liquid on detainees, pouring cold water on naked detainees,

threatening male detainees with rape, sodomizing detainees with chemical lights and

broom sticks, and using military work dogs to frighten and intimidate prisoners with

threats of attack, and in one case actually biting a detainee.xxxii Furthermore, Taguba

found that there were gross differences between the actual number of prisoners on hand

and the official number recorded.xxxiii Prisoners held without record became known as

ghost detainees that intelligence agencies and special military units, including the CIA,

secretly interrogated for their own purposes.xxxiv One detainee, for example, received

several beatings and suffered massive injuries.xxxv Upon looking at the detainee’s

identification number, investigators discovered that he had the same number as another

prisoner.xxxvi

Among the United States own investigation at Abu Ghraib, several other

organizations were horrified by what occurred there and launched their own inquiry. The

International Committee of the Red Cross reported in February 2004 that between 70 to

90 percent of persons detained at Abu Ghraib Prison were innocent and had been arrested

by mistake.xxxvii Human Rights Watch was also involved in the efforts to help the

detainees at the prison and frequently complained to the U.S. Secretary of Defence

Donald Rumsfeld that civilians in Iraq remained in custody month after month with no

charges brought against them.xxxviii

6

Major Players/Leaders:

Between October and December of 2003 a series of sadistic and blatant criminal

abuses took place at Abu Ghraib.xxxix Major General Antonio Taguba reported that the

majority of the abuses were committed by U.S. soldiers of the 372nd Military Police

Company.xl 12 soldiers were court-martialed by the United States Army for their actions

at the Hard Site in Abu Ghraib including; Staff Sergeant Ivan L. Frederick II, Specialist

Charles A. Graner, Sergeant Javal Davis, Specialist Megan Ambuhl, Specialist Sabrina

Harman, Private Lynndie England, and Private Jeremy Sivits.xli All twelve suspects

faced prosecutions based on the charges of conspiracy, dereliction of duty, cruelty to

prisoners, maltreatment, assault, and indecent acts.xlii

Army Private Lynndie England was convicted and found guilty of one count of

conspiracy, four counts of maltreating detainees and one count of committing an indecent

act.xliii England tried to plead guilty before her trial in exchange for an undisclosed

sentencing cap, but a judge threw out her plea.xliv England now faces a maximum

sentence of nine years in prison.xlv

Army Lieutenant Col. Steven Jordan, the former director of the prison’s

interrogation center was not found in any of the photographs taken in Abu Ghraib, but he

has been accused of allowing the mistreatment of prisoners to escalate.xlvi In full, Jordan

has been charged with failure to obey regulations, cruelty and maltreatment of detainees,

and dereliction of duty.xlvii However, Jordan’s lead defence Captain Samuel Spitzberg

contended that although Jordan headed the interrogation center, he spent most of his time

trying to improve the prison’s living conditions.xlviii Spitzberg won the case and Jordan

received one of the lightest sentences within the army, a reprimand.xlix

7

Staff Sergeant Ivan Frederick was initially sentenced to 10 years in prison for

eight counts of prisoner abuse, but the term was reduced to eight years when Frederick

pleaded guilty.l However, as a part of Frederick’s plea he was required to cooperate in

the prosecution of other cases concerning Abu Ghraib abuses.li

Of all twelve soldiers court-martialed the longest prison term was given to

Specialist Charles Graner.lii Graner was convicted on five counts of assault, maltreatment

and conspiracy in connection with the beating and humiliation of Iraqi detainees and is

serving up to 10 years in prison.liii

Aftermath:

The United States Army and Military Intelligence Agency have found their

reputation permanently damaged because of the actions performed at Abu Ghraib

Prison.liv In attempt to redeem themselves, the United States decided in March of 2006 to

transfer the 4,500 inmates at Abu Ghraib to other prisons around the country and return

the prison to Iraqi authorities.lv The prison was reported emptied of prisoners in August,

and on September 2, 2006 Abu Ghraib was closed down and formally handed over to the

Iraqi government.lvi Three years later, in February of 2009 Iraq reopened Abu Ghraib

under the new name of Baghdad Central Prison.lvii The prison had been renovated to

include water-fountains, a freshly planted garden, and a gym complete with weights and

equipment.lviii Unlike Saddam Hussein’s Abu Ghraib Prison, Baghdad Central Prison

will not have to put 40 prisoners in a cell; each chamber has a capacity of eight people.lix

Furthermore, Baghdad Central Prison opened with 3,500 inmates in its system and can

hold up to a maximum of 15,000 prisoners.lx

8

Impact on International Law:

The criminal abuses that occurred at Abu Ghraib prison violated many charters,

and international laws, but none more so than the third and fourth Geneva Conventions.

Both the third Geneva Convention relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War and the

fourth Geneva Convention relative to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War

hold that the United States is responsible for the violations that occurred at Abu Ghraib.lxi

Article 13 and 14 of the third Geneva Convention states that “prisoners of war must at all

times be humanely treated. Any unlawful act or omission by the detaining power causing

death or serious damage of a prisoner of war is prohibited. In particular, no prisoner of

war may be subjected to physical mutilation or to medical or scientific experiments of

any kind. Likewise, prisoners of war must at all times be protected, particularly against

acts of violence or intimidation. Prisoners of war are entitled in all circumstances to

respect for their persons and their honour.”lxii Furthermore, article 76 of the fourth

Geneva Convention declares that “protected persons accused of offenses shall be

detained in the occupied country, and if convicted they shall serve their sentences therein.

They shall, be separated from other detainees and shall enjoy conditions of food and

hygiene which will be sufficient to keep them in good health. They shall receive the

medical attention required by their state of health, and have the right to any spiritual

assistance.”lxiii

The United States of America was one of the first nations to sign the Geneva

Conventions in 1929 and 1949.lxiv However, instead of upholding the treaty, the U.S.

repeatedly violated it by committing monstrous acts of terror. Furthermore, the United

Nations and other countries are incapable of intervening in the United States affairs

9

because they are one of the five permanent members of the Security Council (Nossal,

Legal source).lxv Had any other government proposed an intervention on behalf of the

Abu Ghraib prisoners, the U.S. would surely have vetoed down any UN action (Nossal,

Legal source).lxvi

The United States Army and Military Intelligence Agency suffered professionally

as a result of the actions committed at Abu Ghraib. As a consequence, the U.S. and

others countries have implemented new procedures to ensure detainees are not abused

and military officers are properly trained.lxvii The United States has even revised their

training and procedures manual to clearly define the extent to which guards and

interrogators can put pressure on detainees.lxviii Armies are also starting to reorganize the

way prison guards are trained and a new 55 hour training course has become mandatory

including subjects such as, ethics, values, and rules of the Geneva Convention.lxix

Controversy:

Throughout Taguba’s investigation, he came across several controversial matters

involving the United States government and Abu Ghraib Prison documents. Overall,

there was a general confusion amongst U.S. officers at the prison concerning who had

authority and could give orders. Military Intelligence was given control of the base in

November of 2003, but several soldiers testified that there was a considerable amount of

confusion over the extent of MI authority.lxx When asked why he did not inform his

chain of command about the abuse, Sergeant Javal Davis answered, “I assumed that if we

were doing things out of the ordinary or outside the guidelines, someone would have said

something. Also the [torture] wing belongs to MI and it appeared MI personnel approved

of the abuse.”lxxi However, Military Intelligence claimed they were only following the

10

orders of Lieutenant General Ricardo S. Sanchez, the senior commander in Iraq.lxxii Two

memos issued by Sanchez were sent to MI based on interrogation rules and

procedures.lxxiii The memos included the approval of interrogation techniques such as,

segregation of detainees and deliberately trying to frighten them.lxxiv Sanchez instructed

interrogators to completely control the interrogation environment, including the

detainee’s food, clothing and shelter.lxxv Furthermore, when approached with the subject

of prison abuse in Abu Ghraib the United States Bush Administration was quick to

declare the abuses were conducted by a “few bad apples” who do not represent the U.S.

Army.lxxvi However, critics and the Army’s own Major General Antonio Taguba are

saying that the abuse was systemic and prison guards must have been acting on a higher

power.lxxvii Lieutenant Colonel Steven Jordan even told investigators that the

interrogation center had been put together at the direction of the White House to

consolidate information regarding terrorist activity.lxxviii

Another exceedingly controversial matter involved in the Abu Ghraib Prison case

was discovered when the Criminal Investigation Command discovered two different

forensic reports.lxxix The first report was completed June 6, 2004, in Tikrit, Iraq which

analyzed a seized laptop computer and eight CDs.lxxx 1,325 photos and 93 videos were

found containing detainee abuse from Abu Ghraib Prison.lxxxi The second report was

completed a month later in Fort Belvoir, Virginia, but 12 CDs were analyzed and only

279 photos and 19 videos were found.lxxxii It remains unclear why and how the CID

narrowed its set of forensic evidence.lxxxiii

11

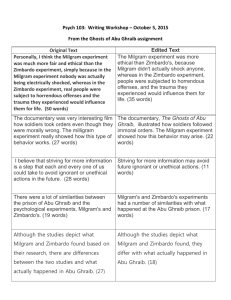

Primary Source:

In August of 2004, 279 photographs were found by the Criminal Investigation

Command in which American soldiers are shown beating, humiliating, and torturing Iraqi

detainees.lxxxiv The photos were taken with cameras belonging to Cpl. Charles A. Graner

Jr., Staff Sgt. Ivan Frederick II, and Spc. Sabrina Harman.lxxxv As a consequence the

images were used as primary evidence against Staff Sergeant Ivan L. Frederick II,

Specialist Charles A. Graner, Sergeant Javal Davis, Specialist Megan Ambuhl, Specialist

Sabrina Harman, Private Lynndie England, and Private Jeremy Sivits in their military

trials.

One of the most iconic images of abuse to emerge from Abu Ghraib Prison

showed a detainee perched on top of a cardboard box, with a hood on his head, a blanket

around his shoulders, and electrical wires extending from his hands.lxxxvi To the soldiers

at Abu Ghraib, the detainee was known as “Gilligan,” but according to CID documents

the prisoner was a man named Saad.lxxxvii

12

Other images of detainee abuse can be found at the following web site galleries:

http://middleeast.about.com/od/iraq/ig/Abu-Ghraib-Torture-Photos/Chip-Frederick.htm,

http://www.salon.com/news/abu_ghraib/2006/03/14/chapter_4/18.html.

Legal Source:

The legal sources I obtained for my final project were Scott Silliman, professor of

international law at Duke University and Kim Richard Nossal, professor of international

law at Queens University. In the case of whether the Abu Ghraib abuses were justified,

Mr. Silliman concluded that the violent acts committed were severe violations of

American and international law. He believes that the atrocities have left a black mark

across the United States military and that the 12 court-martialed soldiers should be held

accountable for their actions. However, in contrast to Mr. Silliman, Canadian professor

Kim Richard Nossal does not appear to disagree or agree with the statement.

Furthermore, Mr. Nossal provided outstanding information concerning the United

Nations lack of involvement in the Abu Ghraib case. Both professors’ answers to my

questions can be found on the following pages.

13

Conclusion:

It has been six years since the infamous torture photographs and videos of Iraqi

prisoners were released and Abu Ghraib Prison still remains a dark hole in American

history. Twelve men and women have been court-martialed and some even face prison

sentences up to ten years, but that does not justify the abuses that occurred. The criminal

investigation on Abu Ghraib Prison taught Canadians and many other nations what the

United States is capable of and what they are willing to do to end “terrorism” in the

Middle East. Furthermore, the Abu Ghraib case has taught many people that every

human is important, no matter their race, gender, or nationality. Every human being

should be treated in the same manner.

14

i

Rowland, Robin. INDEPTH: IRAQ Abu Ghraib. CBC, 6 May 2004. Web. 29 May 2010.

<http://www.cbc.ca/news/background/iraq/abughraib.html>.

ii

Microsoft ® Encarta ® Encyclopedia 2005 © 1993-2004 Microsoft Corporation. All rights reserved.

iii

A BACKGROUND OF ABU GHRAIB. CBC News, 2007. Web. 29 May 2010.

<http://www.cbc.ca/fifth/badapples/history.html>.

iv

A BACKGROUND OF ABU GHRAIB. CBC News, 2007. Web. 29 May 2010.

<http://www.cbc.ca/fifth/badapples/history.html>.

v

Asser, Martin. Abu Ghraib: Dark Stain on Iraq's Past. BBC News, 25 May 2004. Web. 29 May 2010.

<http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/americas/3747005.stm>.

vi

Asser, Martin. Abu Ghraib: Dark Stain on Iraq's Past. BBC News, 25 May 2004. Web. 29 May 2010.

<http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/americas/3747005.stm>.

vii

Asser, Martin. Abu Ghraib: Dark Stain on Iraq's Past. BBC News, 25 May 2004. Web. 29 May 2010.

<http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/americas/3747005.stm>.

viii

Asser, Martin. Abu Ghraib: Dark Stain on Iraq's Past. BBC News, 25 May 2004. Web. 29 May 2010.

<http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/americas/3747005.stm>.

ix

Asser, Martin. Abu Ghraib: Dark Stain on Iraq's Past. BBC News, 25 May 2004. Web. 29 May 2010.

<http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/americas/3747005.stm>.

x

A BACKGROUND OF ABU GHRAIB. CBC News, 2007. Web. 29 May 2010.

<http://www.cbc.ca/fifth/badapples/history.html>.

xi

Asser, Martin. Abu Ghraib: Dark Stain on Iraq's Past. BBC News, 25 May 2004. Web. 29 May 2010.

<http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/americas/3747005.stm>.

xii

Asser, Martin. Abu Ghraib: Dark Stain on Iraq's Past. BBC News, 25 May 2004. Web. 29 May 2010.

<http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/americas/3747005.stm>.

xiii

Asser, Martin. Abu Ghraib: Dark Stain on Iraq's Past. BBC News, 25 May 2004. Web. 29 May 2010.

<http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/americas/3747005.stm>.

xiv

Asser, Martin. Abu Ghraib: Dark Stain on Iraq's Past. BBC News, 25 May 2004. Web. 29 May 2010.

<http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/americas/3747005.stm>.

xv

A BACKGROUND OF ABU GHRAIB. CBC News, 2007. Web. 29 May 2010.

<http://www.cbc.ca/fifth/badapples/history.html>.

xvi

Hersh, Seymour. Annals of National Security Torture at Abu Ghraib. New Yorker, 30 Apr. 2004. Web.

29 May 2010. <http://samizdat.cc/shelf/documents/2004/05.03-hersh/hersh.pdf>.

xvii

Hersh, Seymour. Annals of National Security Torture at Abu Ghraib. New Yorker, 30 Apr. 2004. Web.

29 May 2010. <http://samizdat.cc/shelf/documents/2004/05.03-hersh/hersh.pdf>.

xviii

Asser, Martin. Abu Ghraib: Dark Stain on Iraq's Past. BBC News, 25 May 2004. Web. 29 May 2010.

<http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/americas/3747005.stm>.

xix

Hersh, Seymour. Annals of National Security Torture at Abu Ghraib. New Yorker, 30 Apr. 2004. Web.

29 May 2010. <http://samizdat.cc/shelf/documents/2004/05.03-hersh/hersh.pdf>.

xx

Hersh, Seymour. Annals of National Security Torture at Abu Ghraib. New Yorker, 30 Apr. 2004. Web.

29 May 2010. <http://samizdat.cc/shelf/documents/2004/05.03-hersh/hersh.pdf>.

xxi

Hersh, Seymour. Annals of National Security Torture at Abu Ghraib. New Yorker, 30 Apr. 2004. Web.

29 May 2010. <http://samizdat.cc/shelf/documents/2004/05.03-hersh/hersh.pdf>.

xxii

Hersh, Seymour. Annals of National Security Torture at Abu Ghraib. New Yorker, 30 Apr. 2004. Web.

29 May 2010. <http://samizdat.cc/shelf/documents/2004/05.03-hersh/hersh.pdf>.

xxiii

The Abu Ghraib Files. Salon, 14 Mar. 2006. Web. 29 May 2010.

<http://www.salon.com/news/abu_ghraib/2006/03/14/introduction>.

xxiv

Cohen, Alexander. Special Report: The Abu Ghraib Supplementary Documents. The Center for Public

Integrity, 8 Oct. 2004. Web. 29 May 2010. <http://www.publicintegrity.org/articles/entry/505>.

xxv

Cohen, Alexander. Special Report: The Abu Ghraib Supplementary Documents. The Center for Public

Integrity, 8 Oct. 2004. Web. 29 May 2010. <http://www.publicintegrity.org/articles/entry/505>.

xxvi

Cohen, Alexander. Special Report: The Abu Ghraib Supplementary Documents. The Center for Public

Integrity, 8 Oct. 2004. Web. 29 May 2010. <http://www.publicintegrity.org/articles/entry/505>.

xxvii

Cohen, Alexander. Special Report: The Abu Ghraib Supplementary Documents. The Center for Public

Integrity, 8 Oct. 2004. Web. 29 May 2010. <http://www.publicintegrity.org/articles/entry/505>.

15

xxviii

Cohen, Alexander. Special Report: The Abu Ghraib Supplementary Documents. The Center for Public

Integrity, 8 Oct. 2004. Web. 29 May 2010. <http://www.publicintegrity.org/articles/entry/505>.

xxix

Cohen, Alexander. Special Report: The Abu Ghraib Supplementary Documents. The Center for Public

Integrity, 8 Oct. 2004. Web. 29 May 2010. <http://www.publicintegrity.org/articles/entry/505>.

xxx

Cohen, Alexander. Special Report: The Abu Ghraib Supplementary Documents. The Center for Public

Integrity, 8 Oct. 2004. Web. 29 May 2010. <http://www.publicintegrity.org/articles/entry/505>.

xxxi

Chapter 1: "Standard Operating Procedure". Salon, 14 Mar. 2006. Web. 29 May 2010.

<http://www.salon.com/news/abu_ghraib/2006/03/14/chapter_1/index.html>.

xxxii

Hersh, Seymour. Annals of National Security Torture at Abu Ghraib. New Yorker, 30 Apr. 2004. Web.

29 May 2010. <http://samizdat.cc/shelf/documents/2004/05.03-hersh/hersh.pdf>.

xxxiii

Hersh, Seymour. Annals of National Security Torture at Abu Ghraib. New Yorker, 30 Apr. 2004. Web.

29 May 2010. <http://samizdat.cc/shelf/documents/2004/05.03-hersh/hersh.pdf>.

xxxiv

Cohen, Alexander. Special Report: The Abu Ghraib Supplementary Documents. The Center for Public

Integrity, 8 Oct. 2004. Web. 29 May 2010. <http://www.publicintegrity.org/articles/entry/505>.

xxxv

Cohen, Alexander. Special Report: The Abu Ghraib Supplementary Documents. The Center for Public

Integrity, 8 Oct. 2004. Web. 29 May 2010. <http://www.publicintegrity.org/articles/entry/505>.

xxxvi

Cohen, Alexander. Special Report: The Abu Ghraib Supplementary Documents. The Center for Public

Integrity, 8 Oct. 2004. Web. 29 May 2010. <http://www.publicintegrity.org/articles/entry/505>.

xxxvii

The Abu Ghraib Files. Salon, 14 Mar. 2006. Web. 29 May 2010.

<http://www.salon.com/news/abu_ghraib/2006/03/14/introduction>.

xxxviii

Hersh, Seymour. Annals of National Security Torture at Abu Ghraib. New Yorker, 30 Apr. 2004.

Web. 29 May 2010. <http://samizdat.cc/shelf/documents/2004/05.03-hersh/hersh.pdf>.

xxxix

Hersh, Seymour. Annals of National Security Torture at Abu Ghraib. New Yorker, 30 Apr. 2004. Web.

29 May 2010. <http://samizdat.cc/shelf/documents/2004/05.03-hersh/hersh.pdf>.

xl

Hersh, Seymour. Annals of National Security Torture at Abu Ghraib. New Yorker, 30 Apr. 2004. Web.

29 May 2010. <http://samizdat.cc/shelf/documents/2004/05.03-hersh/hersh.pdf>.

xli

Hersh, Seymour. Annals of National Security Torture at Abu Ghraib. New Yorker, 30 Apr. 2004. Web.

29 May 2010. <http://samizdat.cc/shelf/documents/2004/05.03-hersh/hersh.pdf>.

xlii

Hersh, Seymour. Annals of National Security Torture at Abu Ghraib. New Yorker, 30 Apr. 2004. Web.

29 May 2010. <http://samizdat.cc/shelf/documents/2004/05.03-hersh/hersh.pdf>.

xliii

Lynndie England Convicted in Abu Ghraib Trial. USA Today, 26 Sep. 2005. Web. 29 May 2010.

<http://www.usatoday.com/news/nation/2005-09-26-england_x.htm>.

xliv

Lynndie England Convicted in Abu Ghraib Trial. USA Today, 26 Sep. 2005. Web. 29 May 2010.

<http://www.usatoday.com/news/nation/2005-09-26-england_x.htm>.

xlv

Lynndie England Convicted in Abu Ghraib Trial. USA Today, 26 Sep. 2005. Web. 29 May 2010.

<http://www.usatoday.com/news/nation/2005-09-26-england_x.htm>.

xlvi

2 Charges Dropped as Abu Ghraib Trial Opens. MSNBC, 20 Aug. 2007. Web. 29 May 2010.

<http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/20363524/>.

xlvii

2 Charges Dropped as Abu Ghraib Trial Opens. MSNBC, 20 Aug. 2007. Web. 29 May 2010.

<http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/20363524/>.

xlviii

2 Charges Dropped as Abu Ghraib Trial Opens. MSNBC, 20 Aug. 2007. Web. 29 May 2010.

<http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/20363524/>.

xlix

2 Charges Dropped as Abu Ghraib Trial Opens. MSNBC, 20 Aug. 2007. Web. 29 May 2010.

<http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/20363524/>.

l

Sergeant Is Sentenced to 8 Years in Abuse Case. The New York Times, 22 Oct. 2004. Web. 29 May 2010.

<http://www.nytimes.com/2004/10/22/international/middleeast/22abuse.html>.

li

Sergeant Is Sentenced to 8 Years in Abuse Case. The New York Times, 22 Oct. 2004. Web. 29 May

2010. <http://www.nytimes.com/2004/10/22/international/middleeast/22abuse.html>.

lii

2 Charges Dropped as Abu Ghraib Trial Opens. MSNBC, 20 Aug. 2007. Web. 29 May 2010.

<http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/20363524/>.

liii

Reid, T.. Guard Convicted in the First Trial from Abu Ghraib. The Washington Post, 15 Jan. 2005. Web.

29 May 2010. <http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/articles/A9343-2005Jan14.html>.

liv

Abu Ghraib Set to Reopen as Baghdad Central Prison. The New York Times, 25 Jan. 2009. Web. 29

May 2010. <http://www.nytimes.com/2009/01/25/world/africa/25iht-iraq.1.19652890.html>.

16

lv

Abu Ghraib Set to Reopen as Baghdad Central Prison. The New York Times, 25 Jan. 2009. Web. 29

May 2010. <http://www.nytimes.com/2009/01/25/world/africa/25iht-iraq.1.19652890.html>.

lvi

Abu Ghraib Set to Reopen as Baghdad Central Prison. The New York Times, 25 Jan. 2009. Web. 29

May 2010. <http://www.nytimes.com/2009/01/25/world/africa/25iht-iraq.1.19652890.html>.

lvii

Abu Ghraib Set to Reopen as Baghdad Central Prison. The New York Times, 25 Jan. 2009. Web. 29

May 2010. <http://www.nytimes.com/2009/01/25/world/africa/25iht-iraq.1.19652890.html>.

lviii

Abu Ghraib Now a Humane Prison, Iraq Officials Say. CNN, 22 Feb. 2009. Web. 29 May 2010.

<http://www.cnn.com/2009/WORLD/meast/02/22/iraq.abughraib/index.html>.

lix

Abu Ghraib Now a Humane Prison, Iraq Officials Say. CNN, 22 Feb. 2009. Web. 29 May 2010.

<http://www.cnn.com/2009/WORLD/meast/02/22/iraq.abughraib/index.html>.

lx

Abu Ghraib Now a Humane Prison, Iraq Officials Say. CNN, 22 Feb. 2009. Web. 29 May 2010.

<http://www.cnn.com/2009/WORLD/meast/02/22/iraq.abughraib/index.html>.

lxi

Law Watch: U.S. Responsibility for Violations of the Geneva Conventions at Abu Ghraib Prison. Center

for Defense Information, 17 May 2004. Web. 29 May 2010. <http://www.cdi.org/news/law/gcresponsibility.cfm>.

lxii

Convention (III) Relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War. Geneva, 12 August 1949. international

Committee of the Red Cross, 2005. Web. 29 May 2010.

<http://www.icrc.org/ihl.nsf/7c4d08d9b287a42141256739003e636b/6fef854a3517b75ac125641e004a9e68

>.

lxiii

Convention (IV) Relative to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War. Geneva, 12 August 1949.

international Committee of the Red Cross, 2005. Web. 29 May 2010.

<http://www.icrc.org/ihl.nsf/7c4d08d9b287a42141256739003e636b/6756482d86146898c125641e004aa3c

5>.

lxiv

The United States and the Geneva Conventions. Council on Foreign Relations, 20 Sep. 2006. Web. 29

May 2010. <http://www.cfr.org/publication/11485/>.

lxv

Legal Source, Kim Richard Nossal, Professor of International Law at Duke University

lxvi

Legal Source, Kim Richard Nossal, Professor of International Law at Duke University

lxvii

US Army Reports New Detainee Procedures. Global Security, 24 Feb. 2005. Web. 29 May 2010.

<http://www.globalsecurity.org/military/library/news/2005/02/mil-050224-voa02.htm>.

lxviii

US Army Reports New Detainee Procedures. Global Security, 24 Feb. 2005. Web. 29 May 2010.

<http://www.globalsecurity.org/military/library/news/2005/02/mil-050224-voa02.htm>.

lxix

US Army Reports New Detainee Procedures. Global Security, 24 Feb. 2005. Web. 29 May 2010.

<http://www.globalsecurity.org/military/library/news/2005/02/mil-050224-voa02.htm>.

lxx

Cohen, Alexander. Special Report: The Abu Ghraib Supplementary Documents. The Center for Public

Integrity, 8 Oct. 2004. Web. 29 May 2010. <http://www.publicintegrity.org/articles/entry/505>.

lxxi

Hersh, Seymour. Annals of National Security Torture at Abu Ghraib. New Yorker, 30 Apr. 2004. Web.

29 May 2010. <http://samizdat.cc/shelf/documents/2004/05.03-hersh/hersh.pdf>.

lxxii

Cohen, Alexander. Special Report: The Abu Ghraib Supplementary Documents. The Center for Public

Integrity, 8 Oct. 2004. Web. 29 May 2010. <http://www.publicintegrity.org/articles/entry/505>.

lxxiii

Cohen, Alexander. Special Report: The Abu Ghraib Supplementary Documents. The Center for Public

Integrity, 8 Oct. 2004. Web. 29 May 2010. <http://www.publicintegrity.org/articles/entry/505>.

lxxiv

Cohen, Alexander. Special Report: The Abu Ghraib Supplementary Documents. The Center for Public

Integrity, 8 Oct. 2004. Web. 29 May 2010. <http://www.publicintegrity.org/articles/entry/505>.

lxxv

Cohen, Alexander. Special Report: The Abu Ghraib Supplementary Documents. The Center for Public

Integrity, 8 Oct. 2004. Web. 29 May 2010. <http://www.publicintegrity.org/articles/entry/505>.

lxxvi

Asser, Martin. Abu Ghraib: Dark Stain on Iraq's Past. BBC News, 25 May 2004. Web. 29 May 2010.

<http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/americas/3747005.stm>.

lxxvii

Rowland, Robin. INDEPTH: IRAQ Abu Ghraib. CBC, 6 May 2004. Web. 29 May 2010.

<http://www.cbc.ca/news/background/iraq/abughraib.html>.

lxxviii

Cohen, Alexander. Special Report: The Abu Ghraib Supplementary Documents. The Center for Public

Integrity, 8 Oct. 2004. Web. 29 May 2010. <http://www.publicintegrity.org/articles/entry/505>.

lxxix

The Abu Ghraib Files. Salon, 14 Mar. 2006. Web. 29 May 2010.

<http://www.salon.com/news/abu_ghraib/2006/03/14/introduction>.

lxxx

The Abu Ghraib Files. Salon, 14 Mar. 2006. Web. 29 May 2010.

<http://www.salon.com/news/abu_ghraib/2006/03/14/introduction>.

17

lxxxi

The Abu Ghraib Files. Salon, 14 Mar. 2006. Web. 29 May 2010.

<http://www.salon.com/news/abu_ghraib/2006/03/14/introduction>.

lxxxii

The Abu Ghraib Files. Salon, 14 Mar. 2006. Web. 29 May 2010.

<http://www.salon.com/news/abu_ghraib/2006/03/14/introduction>.

lxxxiii

The Abu Ghraib Files. Salon, 14 Mar. 2006. Web. 29 May 2010.

<http://www.salon.com/news/abu_ghraib/2006/03/14/introduction>.

lxxxiv

The Abu Ghraib Files. Salon, 14 Mar. 2006. Web. 29 May 2010.

<http://www.salon.com/news/abu_ghraib/2006/03/14/introduction>.

lxxxv

Chapter 5: "Other Government Agencies". Salon, 14 Mar. 2006. Web. 29 May 2010.

<http://www.salon.com/news/abu_ghraib/2006/03/14/chapter_5/index.html>.

lxxxvi

Chapter 4: "Electrical Wires". Salon, 14 Mar. 2006. Web. 29 May 2010.

<http://www.salon.com/news/abu_ghraib/2006/03/14/chapter_4/index.html>.

lxxxvii

Chapter 4: "Electrical Wires". Salon, 14 Mar. 2006. Web. 29 May 2010.

<http://www.salon.com/news/abu_ghraib/2006/03/14/chapter_4/index.html>.

18

Works Cited

2 Charges Dropped as Abu Ghraib Trial Opens. MSNBC, 20 Aug. 2007. Web. 29 May

2010. <http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/20363524/>.

A BACKGROUND OF ABU GHRAIB. CBC, 2007. Web. 29 May 2010.

<http://www.cbc.ca/fifth/badapples/history.html>.

Abu Ghraib Now a Humane Prison, Iraq Officials Say. CNN, 22 Feb. 2009. Web. 29

May 2010.

<http://www.cnn.com/2009/WORLD/meast/02/22/iraq.abughraib/index.html>.

Abu Ghraib Set to Reopen as Baghdad Central Prison. The New York Times, 25 Jan.

2009. Web. 29 May 2010. <http://www.nytimes.com/2009/01/25/world/africa/25ihtiraq.1.19652890.html>.

Asser, Martin. Abu Ghraib: Dark Stain on Iraq's Past. BBC News, 25 May 2004. Web.

29 May 2010. <http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/americas/3747005.stm>.

Chapter 1: "Standard Operating Procedure". Salon, 14 Mar. 2006. Web. 29 May 2010.

<http://www.salon.com/news/abu_ghraib/2006/03/14/chapter_1/index.html>.

Chapter 4: "Electrical Wires". Salon, 14 Mar. 2006. Web. 29 May 2010.

<http://www.salon.com/news/abu_ghraib/2006/03/14/chapter_4/index.html>.

Chapter 5: "Other Government Agencies". Salon, 14 Mar. 2006. Web. 29 May 2010.

<http://www.salon.com/news/abu_ghraib/2006/03/14/chapter_5/index.html>.

Cohen, Alexander. Special Report: The Abu Ghraib Supplementary Documents. The

Center for Public Integrity, 8 Oct. 2004. Web. 29 May 2010.

<http://www.publicintegrity.org/articles/entry/505>.

Convention (III) Relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War. Geneva, 12 August 1949.

international Committee of the Red Cross, 2005. Web. 29 May 2010.

<http://www.icrc.org/ihl.nsf/7c4d08d9b287a42141256739003e636b/6fef854a3517b75ac

125641e004a9e68>.

Convention (IV) Relative to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War. Geneva,

12 August 1949. international Committee of the Red Cross, 2005. Web. 29 May 2010.

<http://www.icrc.org/ihl.nsf/7c4d08d9b287a42141256739003e636b/6756482d86146898

c125641e004aa3c5>.

Hersh, Seymour. Annals of National Security Torture at Abu Ghraib. New Yorker, 30

Apr. 2004. Web. 29 May 2010. <http://samizdat.cc/shelf/documents/2004/05.03hersh/hersh.pdf>.

19

Law Watch: U.S. Responsibility for Violations of the Geneva Conventions at Abu Ghraib

Prison. Center for Defense Information, 17 May 2004. Web. 29 May 2010.

<http://www.cdi.org/news/law/gc-responsibility.cfm>.

Legal Source, Kim Richard Nossal, Professor of International Law at Duke University

Legal Source, Scott Silliman, Professor of International Law at Queens University

Lynndie England Convicted in Abu Ghraib Trial. USA Today, 26 Sep. 2005. Web. 29

May 2010. <http://www.usatoday.com/news/nation/2005-09-26-england_x.htm>.

Reid, T.. Guard Convicted in the First Trial from Abu Ghraib. The Washington Post, 15

Jan. 2005. Web. 29 May 2010. <http://www.washingtonpost.com/wpdyn/articles/A9343-2005Jan14.html>.

Rowland, Robin. INDEPTH: IRAQ Abu Ghraib. CBC News, 6 May 2004. Web. 29 May

2010. <http://www.cbc.ca/news/background/iraq/abughraib.html>.

Sergeant Is Sentenced to 8 Years in Abuse Case. The New York Times, 22 Oct. 2004.

Web. 29 May 2010.

<http://www.nytimes.com/2004/10/22/international/middleeast/22abuse.html>.

The Abu Ghraib Files. Salon, 14 Mar. 2006. Web. 29 May 2010.

<http://www.salon.com/news/abu_ghraib/2006/03/14/introduction>.

The United States and the Geneva Conventions. Council on Foreign Relations, 20 Sep.

2006. Web. 29 May 2010. <http://www.cfr.org/publication/11485/>.

US Army Reports New Detainee Procedures. Global Security, 24 Feb. 2005. Web. 29

May 2010. <http://www.globalsecurity.org/military/library/news/2005/02/mil-050224voa02.htm>.

Primary Source:

Abu Ghraib Photo Gallery. About - New York Times, 2003. Web. 29 May 2010.

<http://middleeast.about.com/od/iraq/ig/Abu-Ghraib-Torture-Photos/ChipFrederick.htm>.

The Abu Ghraib Files. Salon, 2003. Web. 29 May 2010.

<http://www.salon.com/news/abu_ghraib/2006/03/14/chapter_4/18.html>.