Clark

advertisement

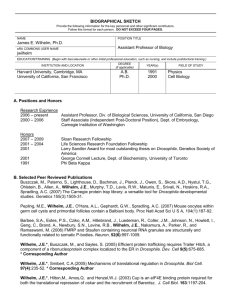

Clark, Christopher. Kaiser Wilhelm II: Profiles in Power. Harlow: Longman, 2000. “History is written by the winner,” the old adage goes, and certainly in the case of Kaiser Wilhelm II this has been borne out. Much of the historiography since the end of World War I has painted Germany’s emperor as everything from an incompetent buffoon to the precursor of the evil of Hitler. Are these perceptions the reality or is there another level that has gone unexplored? With Kaiser Wilhelm II: Profiles in Power, Christopher Clark has produced a work that forces the reader to reevaluate the last emperor of Germany and also take a hard look at the reader’s own biases. The thesis of the work is clearly outlined by the author in the preface. Clark focuses on the nature and extent of the Kaiser’s power, how he “projected authority,” and how much he influenced political policy in his Reich. The author also poses a parallel question: How much difference did it make that it was Wilhelm sitting on the throne during the years leading up to the Great War? Clark does not clutter up his narrative with pedantry- he presents his arguments in a clean and crisp manner that is refreshing to those readers who simply want the facts so they might form their own opinions. To support his arguments, Clark uses extensive endnotes that are conveniently located at the end of every chapter. The simple image of a monolithic German military state under the absolute rule of the Kaiser is a convenient one for those who wish to ascribe the start of the First World War to Germany. Indeed, combined with the emperor’s well-known bombastic utterances it makes a strong case for guilt. The fact of the matter is that the political situation in Germany in the years leading up to the war was very complex. It must be remembered that the German state had only been united for a few decades when Wilhelm ascended to the throne. The nature of political power was constantly changing and shifting between the throne, the Chancellor, and the Reichstag. The emperor had few clearly delineated responsibilities. The power of Bismarck during the early period of German political growth further muddied the waters for his dominance kept the Kaisers from fully exploring and marking their natural boundaries of power. The convoluted nature of the German constitution also confused power issues. For example, responsibility for maintaining the effective strength of the military was given to the Kaiser in Article 63 yet the same responsibility was given to the Reichstag in Article 60. Because of this confusion, there were constant struggles between the emperor and the legislature over military expenditures. The most important avenue of power for Wilhelm was through his right to hire and fire government appointed officials. Yet even this power was often circumvented through the will of the Chancellor, different ministries, or the Reichstag. Some point out that it was this power that gave Wilhelm “institutionalized personal rule.” Clark disagrees and presents convincing evidence that Wilhelm’s chancellors all exercised freedom of action often at the emperor’s expense. Conversely, any argument that holds that Wilhelm was without the means to exercise political prerogatives can be shown to be fallacious by Wilhelm’s appointment of officials “over the head” of his chancellor. These arguments aside, the Kaiser’s overall ability to influence Germany’s political agenda was severely limited. The Kaiser’s near impotence in shaping government policy led him to move deeper into military affairs. His status as commander-in-chief did allow him a measure of freedom of action. Wilhelm, however, was not a creature of the military establishment. In fact, he was often derided as the “Peace Kaiser” by the army’s Prussian hierarchy. Where he found his home was in naval affairs. It was his desire to make Germany a naval power that caused the arms race with Great Britain, a move many see as an important leg on the road to war. Clark sees the arms race as just a manifestation of a more serious issue dividing Great Britain and Germany- global trade. German naval expansion coupled with the seizure and long-term leasing of the Chinese port of Kiaochow was deemed as a major threat to Britain’s dominance in trade. Much has been made of Wilhelm’s personality and how much it affected international relations especially in the critical days leading up to August 1914. Although it is generally accepted that Wilhelm was impetuous, insecure, and given to making outlandish statements, what the author makes clear is that most of the statements regarding Wilhelm to be a firebrand and warmonger are the perspectives of his enemies. In fact, American and Dutch officials found him to be quite “pacific.” It was, and is, easy to use Wilhelm’s personality flaws to pin the blame for the war on him. Clark clearly demonstrates that every document, letter, and utterance by Wilhelm was given much greater importance because of the later events of 1914. A deeper look at the context of the evidence shows another picture of the Kaiser- a man that did all he could with the powers at hand and in the confines of his personality to stop the war from occurring. Concurrently, the reader also comes to see the Entente powers in a new light. Much of the historiography of World War I has been written in an anglophile vein. Great Britain, France, and to a lesser extent Russia, have often been portrayed as the aggrieved parties. Germany’s motives have always been less “pure.” What Clark demonstrates is that the political motivations of the Entente were just as selfish, imperialistic, and provocative as any of those of Germany. Christopher Andrew sums up the political paranoia of the period perfectly: “The diplomacy of imperialism was often based on suspicion and on myth generated by suspicion. Governments were apt to attribute to others their own imperial ambitions.” Clark’s book will disturb even the most partisan anglophiles. Kaiser Wilhelm II: Profiles in Power is a refreshing look at one of the most enigmatic rulers of the early twentieth century. Its balance and objectivity are clearly needed for any thoughtful discussion on why World War I occurred. Clark succeeds in helping define the German pre-war political picture and he rehabilitates the Kaiser to a level where the motives of all the belligerents are suspect and game for blame. Robert Marshall Hist 5423 World War I and Versailles Dr. Jones 19 February 2001