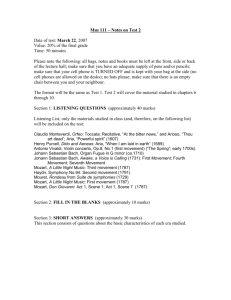

Introduction

advertisement

What Mozart Had and Tracey Hasn’t By: Roger Scruton From: The Sunday Times, May 20, 2001 Exercises: J. Geffen Introduction A liturgy of opposites has developed in the theory of education: creativity versus routine, spontaneity versus rules, imagination versus rote-learning, innovation versus conformity. Rousseau’s myth of the noble savage, good by nature and corrupted by society, lives on; and in the face of all the evidence to the contrary, educationists go on telling us that children learn not by conforming to some external standard, but by “releasing their inner potential” and expressing their creative skills. Hence rote learning, facts and traditional routines are dismissed as irrelevant. 5 10 15 20 1. Children write poetry before they have memorized a single line of it, dance before they have learnt a single step, paint and daub without the faintest knowledge of figurative drawing. They are encouraged to empathise with historical characters, and to express their “geographical skills”, without having the first idea of the history and geography of their country. Grammar, spelling and punctuation are downgraded in the interests of creative self-expression. 2. Imagine an educational guru who told us that nothing mattered in mathematics so much as creativity. Great mathematicians such as Euler, Cantor and Godel were distinguished, the guru tells us, by their imaginative powers. They were able to break through the hidebound rules of their predecessors, to cast aside the ordinary routines of proof, and to take an imaginative leap to conclusions that could never have been reached but for this creative adventure. We should therefore be teaching children to release their mathematical creativity and to value spontaneity against rule-following. We all know what such a philosophy would entail in practice – namely, ignorance. 3. You can be a creative genius in mathematics only if you have acquired the discipline of mathematical proof. When it comes to the hard sciences, therefore, even educationists seem prepared to admit that discipline comes first, creativity later. They recognise that chemistry taught with a regime of pure self-expression would soon degenerate into alchemy, just as “creative” physics would be hard to distinguish from witchcraft. 4. Why do we think that things are so different in the case of language, literature, history and the arts? The answer is to be found in the long tradition of woolly thinking that began with Rousseau. On the one hand, educationists believe, there is the objective world of facts, and this we must explore through disciplined learning and What Mozart Had and Tracey Hasn’t / 2 25 30 35 40 45 50 55 60 65 the building of theories. On the other hand there is the subjective world of opinions, feelings and artistic urges, to be explored through self-expression. 5. Any other approach is considered “authoritarian”. Grammar, style, art, even history are all alleged to be matters of opinion. Hence the purpose of education is to give children the confidence to express their subjective attitudes to these things – subjective attitudes being all that we have. 6. Such thinking is contradicted by the obvious fact that self-expression is not innate but acquired: the self, too, is a social product. We do children a great wrong by withholding the discipline, the knowledge and the store of examples that confer the art of self-expression, since, by doing so, we damage the self. The anger of many young people now leaving school is the anger of the inarticulate. The emphasis on the creative act produces teenagers specialising in acts of destruction. 7. Even in the arts – especially in the arts – the shibboleth of creativity has been counter-productive. Consider Mozart, whose ever-fresh, ever-lucid melodies are among the most original creations of mankind. Mozart did not become a creative genius merely by letting it all hang out, even though he had more to hang out than anyone. He was rigorously and relentlessly schooled by his father, subjected to the ordeal of public performances, trained in the art of memory and in the grammar of the classical style. 8. Of course, Mozarts are few and far between, but it is all the more reason to be as disciplined as Mozart. With the discipline, there is a chance of being creative; without it, there is no chance at all. Visit a British art school for the finalists’ show and you are almost certain to find an array of discarded objects, random cutouts, rehashes of Duchamp’s urinal, maybe just an old coat with the artist’s name-tag pinned to it – all praised and rewarded for their “creativity”, and all as dull and empty as the work of caged chimpanzees. 9. Hardly an art school in our country now insists on figurative drawing, clay modelling, casting, or the mastery of pigments – still less a knowledge of art history, or an ability to discern just why the planes of a Matisse interior intersect at an acute angle, or the shadows of a Constable are done in yellows and browns. 10. Of course, artistic ability is not like scientific knowledge: you cannot acquire it merely by diligent study. There comes a point where a leap of the imagination is required. If in music, art or poetry you say something that has already been said, then you say nothing. In Ezra Pound’s famous dictum, you have to “make it new”, and that means imprinting your words, your notes or your forms with a distinct personality and an inimitable life. 11. The myth that we are all instinctively creative goes hand-in-hand with the belief in originality as the sole criterion of artistic merit. And, when rules and disciplines are rejected, the only proof of originality becomes the ability to shock or surprise. Nothing that Mozart did was intended to shock his audience, or to surprise them with some outrageous gesture. The originality of his music is inseparable from its rule- What Mozart Had and Tracey Hasn’t / 3 70 75 80 guided objectivity. It has a logic and an orderliness that come from the supreme grasp of musical grammar. 12. Real originality does not defy convention but depends on it. You can only “make it new” when the newness is perceivable, which means departing from conventions while at the same time affirming them. Hence originality requires tradition if it is to make artistic sense. 13. But what about the rest of us? Why should we, who are not geniuses, acquire the knowledge needed by those who are? This is a difficult question, but it is really tantamount to asking why schools should teach art, literature and music at all. I like to believe that people who acquire artistic, musical or literary skills, but who lack the divine spark, are nevertheless an addition to the common good. We don’t go to galleries to see exhibitions of Victorian watercolourists. But their paintings gave pleasure to themselves and their neighbours, and still give pleasure today. 14. People who have learnt poetry by rote and who know how to compose the occasional sonnet may not revolutionise the consciousness of mankind as Shakespeare, Wordsworth or Baudelaire did. But they are likely to understand what those great writers were saying, are likely to live on a more exalted plane as a result of doing so, and are also able, through their life and example, to make a positive contribution to the great war against Dullness. What Mozart Had and Tracey Hasn’t / 4 Answer in your own words. Answer the question below in English. 1. What does the introduction suggest about the author’s approach to the traditional methods of learning? Substantiate. Answer: _________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________ Answer the question below in Hebrew. 2. Those engaged in the teaching practices referred to in paragraph 1 support a certain theory. What is it? Answer: _________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________ Answer the question below in English. 3. What does the example of Euler, Cantor and Godel (paragraph 2) illustrate? Answer: _________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________ Answer the question below in English. 4. What prerequisite would a mathematician have to meet in order to engage in creative work? (paragraph 3) Answer: _________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________ Answer the question below in Hebrew. 5. Why is discipline condemned by those who emphasize artistic creativity? (paragraphs 4-5)? Answer: _________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________ Answer the question below in English. 6. What is Mozart’s career meant to illustrate? (paragraph 7) Answer: _________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________ What Mozart Had and Tracey Hasn’t / 5 Answer the question below in English. 7. What does the fact that students in most art schools no longer learn figurative drawing suggest about their tutors’ approach? (paragraph 10) Answer: _________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________ Answer the question below in Hebrew. 8. In the absence of rules and regulations how could originality be shown? (paragraph 11) Answer: _________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________ Answer the question below in Hebrew. 9. Why does real originality require convention and continuity if it is to be perceived as such? (paragraph 12) (Not clearly stated but inferred) Answer: _________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________ Answer the question below in Hebrew. 10. Why should even moderate artistic achievements or abilities be tolerated and encouraged? (paragraph 13) Answer: _________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________ Choose the best answer. 11. The writer does not include the Victorian watercolourists among the (paragraph 13) a. painters. b. craftsmen. c. the great masters. d. amateurs. Answer the question below in Hebrew. 12. What is the main message of this article and for whom is it intended? Answer: _________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________ What Mozart Had and Tracey Hasn’t / 6