Dear Colleagues All,

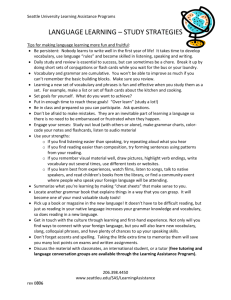

advertisement