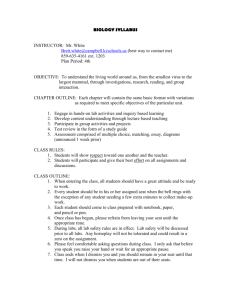

Teri and I standing beside the Pinto on a purple

advertisement

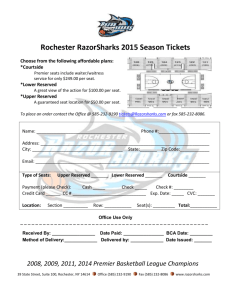

Teri and I standing beside the Pinto on a purple Absarokee morning. It’s five AM, and we are about to sneak out of Montana, sneak out of our skins and into new ones. We’ve told nobody our real plans: Teri told her mother she was moving to New York, I told my folks I was moving to Boston – but we let all of them draw the inference about our leaving together for themselves. Teri’s parents are devout Lutherans, and she is their baby – they don’t want to let her go, and the idea that Teri may not only be moving far away but may also be moving into an apartment in that far-away place with a man she isn’t married to is more than we think they can take. Or at least that’s what we don’t tell ourselves when we don’t think about it. As for my Catholic parents, equally devout – well, I’ve been lying to them now for so long that it seems pointless to try another tack. We buy the Pinto in Helena – a ’72, rust brown, advertised in the paper for $400. We go to check it out, and the owner – to us just another oldish guy in a house in Helena with one more car than he wants – asks us what we want it for. We tell him we’re going to pack it up and drive it across the country. He gives us half our money back and says good luck. He looks worried. Or puzzled. Teri and I fell into each other in my last year of college at Bozeman. Both of us were already spoken for – Teri had plans to marry a boy from Bozeman, and I was attached to Lori, a girl I’d met the year before while on exchange at Amherst. Teri and I each saw in the other almost instantly what we needed, and what we each needed was not so much lover or partner as accomplice. Each of us wanted out, wanted to shake Montana’s dust off our feet, and neither of us was strong enough to do it alone. We bluffed for each other, bluffed strength and bluffed not caring. There was an air of inevitability about all of it, like we stepped on a train in a classroom in Bozeman in January and that train would not stop until it reached Boston in July. I broke up with Lori on the phone, and was slightly puzzled that she didn’t grasp the inevitability, couldn’t hear the train and know she wasn’t on it – I almost thought she would wish me well, her on the platform waving a handkerchief at my closed sleeping-car window. Anyway, she didn’t, and Teri blew off the boy in an equally offhand way. We were not thoughtless – just absolutely focused on our escape, more than we knew, and egging each other on we made everything and everybody else secondary. We were gone. Outta here. We laughed a lot then, and talked a lot about love and life and the city, the city, the city. So it’s five o’clock in Absarokee, the Pinto’s loaded, and we’re ready to go. We’re both sleepy, but so agitated with adrenaline it doesn’t matter. We’d stopped here for one day and one night to see my brother’s wedding, a big do at my folks’ place on the Stillwater. We’re now in the driveway of that place. We can hear the Stillwater in the background, mountain water flowing north and east here on its way to meet the Yellowstone at Columbus, and then the Missouri at Glendive, the Mississippi in St. Louis. The sound of that eastward flow is not a restful burbling, but relentless and loud, like a truck on the highway that never goes by. All day the day before I’d hovered above the wedding, not saying goodbye to my family, not allowing them to say goodbye to me. In my mind I was already gone; I’d stopped paying attention. The cord, to me in the morning, seems already cut and I’m floating emotionless above the Stillwater valley, above “Green Pastures,” as my dad likes to call the place because of the Stillwater reference and because it pleases his Irish Catholic ear. Dad and I haven’t talked for six years except in angry tones and embarrassed monosyllables. I don’t expect to see him now – and I don’t. The whole thing feels at once momentous and anticlimactic. Are we exploding into a new life, or are we just sneaking out of town? Difficult to say, but we go before we can ask the question, much less answer it. So we leave without saying goodbye, and aim the Pinto at the purpling spot on the horizon that marks the East. When I’m going on a long trip I always leave early so I can catch an hour or two on the sun. The best hours in a car are those early morning hours. Everything’s in front of you, and by breakfast you’ve already gone a long way. *** Dad loves to drive. he has that in common with many Montanans, who have to drive long distances to get anywhere, and he will later have that in common with me. It is again the early morning, it is again summer. I am seven years old. I am wearing my PJ’s. I like it in the front seat, and I never sleep away the beginning of a trip – unlike the rest of the kids, I don’t fight over a spot in the back of the station wagon, where you can sack out stretched out until breakfast in Big Timber. In the front I can sit between Mom and Dad, and I can watch the road unfold in front of us; or I can sit in the window seat when the sun comes up with my hand out the window like an airplane wing – I make it hop hop hop over the fenceposts just beyond the barrow pit. The front seat smells like yesterday’s shaving soap. It smells like my Dad. We’re in the big white station wagon, a used limo my Dad picked up cheap somewhere, so long it has to have running lights like a semi but my Mom can parallel park it in one swift motion almost without looking behind her. It has an extra back seat – that is, instead of front seat, back seat, wagon back, it’s front seat, back seat, another back seat, wagon back. Almost all of us are in it: me, Mom and Dad in the front; Pat, Kate and Eileen behind us, Rolly and Jenny behind them, Margi and Martha stretched out on sleeping bags in the back. Anne and Mary are away at school. Tom is away, too, I don’t know where – maybe the navy, maybe Viet Nam, maybe Afghanistan. He’s away. (My sisters, bored around the tree three Christmases ago, had tutored me in the order of my family’s thirteen names, until “Annetommarypatkateeileenrollymargijennymarthajohnandmomanddad” became a single word to me, twenty-one syllables to be forever remembered not in my cerebrum with the recipes and the phone numbers but somewhere else, maybe in my spinal cord, where also was the “SheehyresidenceJohnspeaking” I had to memorize in order to answer the phone, where also would be the Hail Mary, Our Father and all the Acts of Contrition and Faith I would later learn in school. They became responses to stimuli – tap my knee and my leg will jerk, ring my phone and I’ll say SheehyresidenceJohnspeakking. I have, when sleepy, picked up a ringing phone and said HailMaryfullofgracethelordiswiththee by accident. The wires of reflex get crossed, the meaning of the words not remembered but forgotten by dint of constant repetition.) We’re heading west and there is a sign that says “city limits.” I – the “I” who is talking to you, the timeless, ageless I of narrative memory – step outside of the “I” who is sitting in the car, and for the first time in my life I see myself in my place, imagine the world completely from above: from that vantage point, I see a child in a car full of children. Behind them is everything they know, everybody they know, the whole of their human world. In front of them is space – fifty, a hundred miles of beautiful starry nothingness, and because this is the dry high desert they can see it all, and may even like it, but they drive fast because they want to get across it to make re-entry into their human world in Butte. The child in the front seat feels something like loneliness in the face of all that empty space but can’t name it because I’m the part of him with the names for things, and I watch him feel it but don’t feel it myself from above. Then I am approaching him and his feeling has just passed and he realizes he is in a car and that car contains in human flesh almost all of the twenty-one syllables of his family’s real name. And I am in him again when he thinks this is what love is. And what missing is – Anne, Tom, Mary. The child knows they will return in the dark, late at night, just as he knows they will go to Columbia Gardens in Butte and will ride the merry-go-round with the handcarved horses and eat ice cream and ride the roller coaster and puke and be admonished. The child knows that he’d better go now because we’re not stopping until we get there. But the child knows they will return in the dark and will sneak up on Billings from behind, until they get to the road on the top of the Rims. The child knows that his father will be angry at one of them or all of them at least once that day, and that the anger will come out of nowhere and hit hard and be unforgiving, that it may descend as cuff or buckle or, more likely, as a humiliating dismissal, that it will linger then in the car and beyond it like a smell. The child knows that the smell will not be gone, but dissipated, a space cleared, when the stars are out above the Rims and the green dashboard light frames his father’s face against a black car window – tired now, the mad all out of him – and the child’s eyes will slowly open and his ears will open and he’ll hear KGHL playing country music down low and he’ll sit up and look to his right and his father will say “The jewelbox” softly to whomever is awake when the lights of Billings appear below to fill the coulees and butt up against the sandstone bluffs of the Yellowstone valley.