In 'The *Woman at the Store', 'Millie' and 'Ole Underwood', she

advertisement

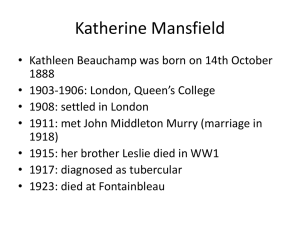

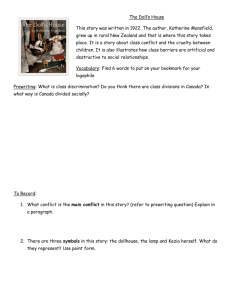

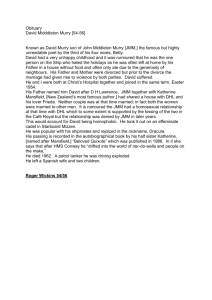

In ‘The *Woman at the Store’, ‘Millie’ and ‘Ole Underwood’, she moved the popular colonial low-brow yarn towards a fresh psychological depth and an awareness of impressionist technique. http://www.bookcouncil.org.nz/writers/mansfieldk.html Biographical entry by Vincent O'Sullivan MANSFIELD, Katherine (1) (1888–1923), was born in Wellington as Kathleen Mansfield Beauchamp, into a family with vigorous social ambitions. Her mother was the delicate and aloof Annie Dyer; her father, Harold Beauchamp, a canny and successful businessman. A first cousin in Sydney became the best-selling novelist, and Mansfield’s first role model, Elizabeth von Arnim. Mansfield’s early school years were spent in Karori, a village in the hills a few miles from Wellington, until the Beauchamps returned to Wellington, to an impressive merchant’s mansion and a more select social programme, when she was 11. At first she attended Wellington GC, then Miss Swainson’s private school. In 1903 Beauchamp, now director of the Bank of New Zealand, chose Queen’s College, Harley Street, London, an institution founded by Charles Kingsley for the liberal education of women, to add metropolitan polish to his clever and handsome daughter. She immersed herself in French, German and music, and began writing sketches and prose poems. In the Queen’s College Magazine she published ‘About Pat’, her first re-creation of childhood in Karori, written in direct and simple prose, as well as ‘Die Einsame’, redolent with fin-de-siècle motifs and symboliste elaboration of mood. The New Zealander and the European had begun their never quite resolved engagement. Kathleen Beauchamp returned to Wellington, rebellious and unsettled, in late 1906. Although her life was comfortable and socially expansive, for the next twenty months she warred against parental vigilance, and found Wellington understandably provincial. She filled what she later called ‘great complaining notebooks’, published her first work under noms de plume in The Lone Hand and The Native Companion in Australia, and moved through a number of furtive infatuations with men and women. She also made an extended caravan journey into remote Urewera country in the middle of the North Island, her one experience of ‘roughing it’, returning home with a liking for Maori and English tourists, ‘but nothing in between’. Her father accepted her plea for musical training in England and she arrived again in London in August 1908, ‘Katherine Mansfield’ already decided on as her pen-name. Within weeks life was, as she had hoped, complex and sophisticated. She was in love with Garnet Trowell, a young violinist whose father had taught her the cello in Wellington. When the affair collapsed some months later, she impulsively married G.C. Bowden, a singing teacher whose name she officially bore for the next nine years, but whom she left the day after the marriage. She returned to Garnet, travelled with his opera company, became pregnant, and again separated. During those months she depended, as she was to do for the rest of her life, on her close but exasperating friendship with Ida Baker, her Rhodesian school chum from Queen’s College. Usually referred to as L.M. (‘Leslie Moore’) or Jones, she was also variously nicknamed over the years as the Albatross, the Cornish Pasty, the Faithful One. A coldly efficient Annie Beauchamp, wrongly suspecting an ‘unhealthy’ friendship with Ida, arrived from New Zealand to install her daughter at Wörishofen, Bavaria, hoping that the famous water cure might restore normality. After the birth of a stillborn child, Mansfield stayed on in *Germany until the next January. She formed a liaison of sorts with the Polish translator, journalist and con-man, Florian Sobienowski. Later he would attempt to blackmail her with letters she wrote at this time, but he encouraged her to read Russian writers, especially Chekhov, and was indirectly responsible for her finest poem, ‘To Stanislaw Wyspiansky’. Ostensibly a tribute to a Polish patriot and poet, it prompted her to consider her own country, ‘Making its own history, slowly and clumsily / Piecing together this and that, finding the pattern, solving the problem, / Like a child with a box of bricks’ and remarking of herself, with a Whitmanesque bravura, ‘I, a woman, with the taint of the pioneer in my blood’. The months in Bavaria also provided the occasion for the satirical stories she began contributing to A.R. Orage’s journal, the New Age, once she was back in England. The stories spared neither Germans nor family life, and presented sex, pregnancy and social divisions with almost ferocious candour. These New Age stories, and a number of others, were collected in 1911 as *In a German Pension. As well as presenting her as a fresh and incisive voice, Mansfield’s association with the respected Fabian weekly led to a close and ultimately bitter friendship with Orage’s eccentric South African mistress, Beatrice Hastings. Still dependent on Ida Baker’s homely loyalty, but drawn to the modish insouciance of her new literary circle, Mansfield took her most decisive turn when, at the end of 1911, she met the precociously gifted, lower-middle-class Oxford undergraduate, John Middleton *Murry. He was already the founding editor of Rhythm, a quarterly self-consciously dedicated to the spirit of Modernism, to Mahler in music, Post- Impressionism in art, and Bergson in philosophy, yet calling also for ‘guts and bloodiness’, an escape from both Englishness and aestheticism. It was a call that brought from Mansfield the small group of New Zealand stories that depicted the emotional and physical violence of raw colonial life. In ‘The *Woman at the Store’, ‘Millie’ and ‘Ole Underwood’, she moved the popular colonial low-brow yarn towards a fresh psychological depth and an awareness of impressionist technique. Although Dan *Davin excluded them from his Selected Stories (Oxford University Press, 1953) as dealing ‘with scenes she had glimpsed only superficially’, they are an essential part of her oeuvre, the first New Zealand stories to thread human behaviour with the brooding grimness of landscape. In a much-quoted sentence from ‘The Woman at the Store’, which Allen *Curnow took up as epigraph to his Penguin Book of New Zealand Verse (1960), she noted ‘There is no twilight in our New Zealand days, but a curious half-hour when everything appears grotesque—it frightens—as though the savage spirit of the country walked abroad and sneered at what it saw.’ Within weeks of meeting, Mansfield and Murry had set up house together, assuming the literary role of ‘the two tigers’, and begun their habit of addressing each other as Tig and Wig. Her new allegiances drew a series of savage satirical attacks in Orage’s portrait of her as ‘Mrs Foisacre’ in the New Age. When Rhythm folded in mid-1913, she and Murry jointly edited the three issues of its successor, the Blue Review. Soon after they began an intense and troubled friendship with D.H. *Lawrence and Frieda Weekley, at whose marriage they featured as official witnesses. At the end of the same year, their attempt to set up as writers in Paris was cut short by Murry’s bankruptcy in the wake of his collapsed journals. Mansfield had written only *‘Something Childish but Very Natural’, and life back in England meant frequently changed addresses and meagre funds. Soon after the outbreak of World War 1, they moved to Great Missenden, with the Lawrences not far off, and Mansfield began her deep and lasting friendship with the Ukrainian Jew, S.S. Koteliansky. When her relationship with Murry seemed close to falling apart, she set out for Paris in early 1915, to the borrowed apartment of the French novelist, journalist and committed bohemian Francis *Carco. But first she visited Carco at Gray, in the Zone des Armées where he was posted. The brief affair contributed to her war story, ‘An *Indiscreet Journey’, as did Carco himself to the cynical roué, Raoul Duquette, three years later in her ‘cry against corruption’, *‘Je ne parle pas français’. Before her return to Murry, Mansfield began in The *Aloe what she hoped would be a novel based on her own family, and the move when she was a child from Tinakori Road to Karori. Memories were further revived when she met up with her beloved younger brother Leslie, who had joined a British regiment. For the Autumn issue of the Signature, a short-lived periodical put together by Murry and Lawrence, she wrote ‘The *Wind Blows’, an exquisitely controlled recreation of adolescence and the Wellington of her girlhood. But the enduring motive for a return to New Zealand settings, and her intense focusing on both memory and a new narrative technique, was the death of her brother in Belgium in October 1915. As she wrote soon after, ‘the form that I would choose has changed utterly. I feel no longer concerned with the same appearance of things.’ Two years later, when Virginia Woolf asked for a story for her Hogarth Press, Mansfield reshaped The Aloe into *Prelude (1918). Now a shorter fiction in twelve discrete sections that cut and overlap in a method she derived from cinema, it ran together symbolism and realism with a vivid emotional resonance, achieving ‘that special prose’ she equated with both elegy and celebration. ‘And won’t the "Intellectuals" just hate it’, she said. ‘They’ll think it’s a New Primer for Infant Readers. Let ’em.’ She continued to mine her early memories, while also writing clever, more brittle stories, such as *‘Bliss’ and ‘Psychology’, that drew on her friendship with the Garsington and Bloomsbury ‘sets’, and allowed her the satirical stance that was also a selfprotective play. Mansfield’s friendship with the Lawrences had reached crisis point in Cornwall in mid-1916. Although she felt Lawrence’s dark spasms of rage were so close to her own temper, the ‘dear man’, as she wrote to a mutual friend, had become lost in ‘the immense german Christmas pudding which is Frieda. And with all the appetite in the world one cannot eat one’s way through Frieda to find him.’ She grew closer to Lady Ottoline Morrell and, more cautiously, to Virginia Woolf. For a time Maynard Keynes was her landlord, Lytton Strachey was attracted to her because she was like a Japanese doll, Bertrand Russell admired her mind and attempted an affair, while T.S. Eliot warned Ezra Pound she was ‘a dangerous woman’. But Mansfield’s wary colonial elusiveness allowed more relaxed friendships with artists and the mildly eccentric—for a time, with the East End painter Mark Gertler, and the androgynous Carrington; more enduringly, from 1912 onwards with the Scottish painter J.D. Fergusson, and the American Anne Estelle Rice, whose portrait of her is in the National Museum in Wellington; and increasingly with the deaf aristocrat, Dorothy Brett, who also painted. But it was illness, rather than choice, that led to her gradual separation from most of her friends in England. From early 1918, when her tuberculosis became a matter of serious concern, Mansfield moved constantly between London and the Riviera. Even after her marriage to Murry in mid-year, she remained dependent on Ida Baker as companion and quasi-nurse, while Murry was committed to his war work in MI5, then later to his journalism. With various winterings-over in Bandol, Ospedaletti, San Remo and Menton, and summers back in Hampstead, Mansfield accumulated enough stories to put together Bliss and Other Stories (1920). In early 1919 Murry had taken over editorship of the Athenaeum and separation, reuniting, and again separation established itself as the rhythm of their lives, while there flowed between them a highly charged correspondence. Mansfield’s letters were always an amalgam of wit, joie de vivre, and direct emotional exchange. Those written to Murry took on the added poignancy of a constant but frequently tested love, with the sharp tracing of her illness in the recurring sequence of elation as she first moved, regret and confusion while they were apart, then restored delight. Her vivacity and frankness as a correspondent increasingly prompts critics to value her letters as highly as her fiction. Taken with her numerous notebooks, they offer a richly detailed account of a modern woman’s engagement with love, art, solitude, impending death and war. ‘The war is in all of us,’ she wrote, even after hostilities were over, as she increasingly drew an analogy between the corruptions of civilisation and her own physical decay. The most fruitful period in Mansfield’s creative life began when she rented the Villa Isola Bella in Menton in September 1920. In the previous eighteen months, much of her energy had gone into almost weekly reviews for the Athenaeum, and translations of Chekhov’s letters, in collaboration with her friend Koteliansky. Although diverting and astute, she seldom had the chance in her reviews to discuss any but inferior fiction. She was now determined to concentrate on her own work—‘they are already chopping down the cherry trees’, as she wrote in her awareness of limited time. At Menton she wrote the bitter and posthumously published ‘Poison’, touching again on the tensions of her marriage, but also the compassionate *‘Miss Brill’ and ‘The *Stranger’, and ‘The *Daughters of the Late Colonel’, which attracted critical acclaim and the admiration of Thomas Hardy, when published in the London Mercury in May 1921. That same month Mansfield left for Switzerland, where she and Murry, who had resigned from the Athenaeum, took a chalet at Montana-sur-Sierre. She worked diligently to produce made-to-measure stories for the high fees paid by the Sphere, but also some of her strongest New Zealand stories—‘I long, above everything else, to write about family love.’ Returning to the characters of Prelude, and her own projection as the child Kezia, she wrote *‘At the Bay’, as well as *‘Her First Ball’, ‘The *Garden Party’, ‘The *Doll’s House’, and in a very different key, the enigmatic and unfinished ‘A *Married Man’s Story’. Disillusioned with current medical practice, Mansfield decided on an expensive and useless X-ray treatment. The move to Paris early in 1922 brought her into the circle of Russian emigré intellectuals, while her own reading of Ouspensky, her conviction that she must now ‘risk anything’, and the renewed influence of her early mentor Orage, led her to seek a cure that was spiritual as much as physical. She wrote little in Paris, but early in the year produced ‘The *Fly’, her classic final statement on war, futility and courage, and the last of her many attempts to depict her father. In her final story ‘The *Canary’, the image of the singing and ailing bird is to some extent a representation of herself and the limitations of her own writing, a low-key elegy in which grief becomes acceptance and, ultimately, mystery. After a brief return to Sierre, and two months in London, in October Mansfield entered the Gurdjieff Institute for Harmonious Development at Fontainebleau. Commentators and biographers remain troubled by her decision to place herself under the direction of a guru who is often presented unsympathetically, and to live in a commune of Russians and truth-seekers—‘my people at last’, as she called them. Although Gurdjieff treated her kindly, she was by no means a disciple. Her quest was very much along personal lines, a movement against what she regarded as the crippling intellectualism of post-war European life. In almost her last letter, she declared her goal to be total honesty. ‘If I were allowed one single cry to God, that cry would be: I want to be REAL.’ She died at Fontainebleau on 9 January 1923, a few weeks before the publication of The Garden Party and Other Stories, which confirmed her place among the Modernists of her generation. Murry was criticised by his contemporaries, and savagely satirised in Aldous Huxley’s Point Counter Point (1928), for his enthusiasm in publishing his wife’s literary remains, and by later critics for his reverential management of her reputation. But our debt to him is considerable. From her uncollected and unpublished stories he produced The Doves’ Nest and Other Stories (1923) and Something Childish and Other Stories (1924). He followed these with Poems (1924), The Journal of Katherine Mansfield (1927), the two-volume The Letters of Katherine Mansfield (1928), The Aloe (1930), Novels and Novelists (1930), The Scrapbook of Katherine Mansfield (1937), Katherine Mansfield’s Letters to John Middleton Murry, 1913–1922 (1951) and a misnamed ‘Definitive Edition’ of the Journal of Katherine Mansfield (1954). There have been numerous editions and collections of Mansfield’s stories in over twenty languages, although Antony *Alpers’s The Stories of Katherine Mansfield (1984) was the first scholarly edition, establishing definitive texts. A comparative text of ‘The Aloe’ with ‘Prelude’ (1982), an enlarged edition of Poems (1988) and The New Zealand Stories of Katherine Mansfield (1997) were edited by Vincent O’Sullivan. Four of the five volumes of The Collected Letters of Katherine Mansfield, edited by O’Sullivan and Margaret Scott, have appeared between 1982 and 1996. The Journals, edited by Margaret Scott, were published in two volumes in 1997. Alpers’s The Life of Katherine Mansfield (1982), successor to his ground-breaking Katherine Mansfield, A Biography (1953), remains the fullest and essential account of her life. Other biographical studies include Ruth Elvish Mantz and J.M. Murry, The Life of Katherine Mansfield (1933), Jeffrey Meyers, Katherine Mansfield (1978) and Claire Tomalin, Katherine Mansfield: A Secret Life (1987). VO Mansfield, Katherine (1888-1923) Think Virginia Woolf, but with bodies attached to those ever-so-sensitive minds. That gives you one idea of Katherine Mansfield's writing. Her stories share the fine perception and sensibility of Woolf's novels but her characters are not separate from from the physical world. They are engaged in it. As was Mansfield herself. She was known as quite the female libertine for her time. Travelling around. Sleeping around (with both sexes). Thinking around. Experimenting around. Nothing that Woolf and her Bloomsbury crowd didn't indulge in, mind you, but without their well-bred manners and cover of intellectualism. No wonder Woolf considered Mansfield cheap and whorish, while Mansfield found the slightly older author a prig. (They did seem to have enjoyed discussing writing with each other though. There is even a book available on their intense literary relationship, Katherine Mansfield and Virginia Woolf: A Public of Two.) The difference in Mansfield's personality perhaps translates in her writing into a greater grounding in the everyday concerns of ordinary people—people with flesh and blood, not just theoretical entities. This may be a vast simplification. We have very little of Mansfield's work to compare, a few collections of short stories published in just over a decade. Mansfield died young from tuberculosis she is thought to have contracted from D.H. Lawrence. (She is thought to have been the model for the devilishly uninhibited Gudrun in Lawrence's The Rainbow and Women in Love.) Yet her work is regarded as having greatly influenced short-story writing right up to the present. Along with Joyce (in Dubliners) and several other writers of her time including Lawrence and Woolf, she was an originator of the modernist style, eschewing straightforward narrative to build up each story through the accumulation of finely observed, seemingly inconsequential moments. You may or may not appreciate this transformation of writing (or the later post-modernist, further fragmentation of plot and sense), but you have to accept that almost every serious writer today adopts this approach to some extent. Even writers of popular genres and escapist literature include some of the techniques developed by these writers. Not to do so would make their stories seem too old-fashioned or corny. The locale's of Mansfield's stories are divided among New Zealand where she was born and raised, England where she finished her education and Europe where she lived the last half of her short life. The early ones were written for literary magazines to which she contributed regularly. From 1912 she was associated with Rhythm, a modernist publication edited by John Middleton Murry who became her second husband in 1918 and her champion after her death. (Her first marriage, which lasted effectively only a day, she said was research for a story to see what it felt like.) Only three collections of her stories were published during her lifetime. In a German Pension came out in 1911 after her experience of pregnancy and losing the child in Bavaria. A short story "Prelude", often considered her best, was published by Woolf's Hogarth Press as a book in 1918 and appeared again in the collection Bliss and Other Stories in 1920. As she was dying of TB, she rushed to complete stories for her most influential collection The Garden Party and Other Stories in 1922. Two more books of stories, The Dove's Nest (1923) and Something Childish (1924) were published posthumously. Stories of Katherine Mansfield, a best-of selection, appeared in 1930. Collected Stories was published in 1945. Anthologies of her letters, journals and reviews have also been produced since her death. Author Profile For at least thirty years after her death, the public’s interest in Katherine Mansfield’s tragic, short life overshadowed what little critical attention her literary works attracted. Born to a large, upper-middle-class Wellington family, at age fourteen Mansfield travelled to England to attend Queen’s College. In England, her contemporaries viewed her as a colonial, and as a result, as somewhat of an outsider. Upon graduating at age eighteen, (1906) she returned to New Zealand, only to find that she was equally out of place in what she now viewed as a provincial and cultureless New Zealand. Her two-year stay in New Zealand did prove fruitful, however: During this time she developed a taste for the writings of Oscar Wilde and the other aesthetes, and she began to experiment with a series of pseudonyms, identities, and sexualities. She also travelled around New Zealand, collecting impressions of colonial and family life that would surface in her some of her best stories. After returning to England, getting pregnant, suffering a miscarriage, and marrying and leaving a man she hardly knew, Mansfield began her career as a writer, publishing her first collection of stories, In a German Pension. The same year she met John Middleton Murry and embarked on a tempestuous romantic and literary relationship that would continue until her death. With Murry, Mansfield wrote for and helped edit Rhythm, The Signature, and The Athenaeum magazines. During the last years of her life Mansfield experienced serious health problems stemming from undiagnosed tuberculosis. In an effort to find a cure and a home, she traveled back and forth between England and the Continent. Not surprisingly, a sense of alienation and displacement colors her later, and perhaps most poignant works, such as “Miss Brill,” “The Life of Ma Parker,” and “The Doll’s House.” Her search for stability eventually led her to write stories about what she called “the undiscovered country,” her native New Zealand. “The Woman at the Store” and “Ole Underwood” are local color stories, in the tradition of Kate Chopin and Sarah Orne Jewett, which draw upon dialect and customs to establish scenes and characters. Mansfield’s ambivalent nostalgia for her New Zealand home and family also surfaces in her thinly veiled evocations of her childhood, “Prelude,” “At the Bay,” and “The Garden Party.” After her premature death at age thirty-four, her husband circulated a romanticized image of her life, and of his relationship with her, by publishing edited selections of her letters and diaries. These enjoyed great success, and it was not until the 1980’s that a clear sense of their marital problems, numerous affairs, and health problems became public knowledge. Satire is strictly a literary genre, but it is also found in the graphic and performing arts. In satire, human or individual vices, follies, abuses, or shortcomings are held up to censure by means of ridicule, derision, burlesque, irony, or other methods, ideally with the intent to bring about improvement.[1] Although satire is usually meant to be funny, the purpose of satire is not primarily humor in itself so much as an attack on something of which the author strongly disapproves, using the weapon of wit. A very common, almost defining feature of satire is its strong vein of irony or sarcasm, but parody, burlesque, exaggeration, juxtaposition, comparison, analogy, and double entendre are all frequently used in satirical speech and writing. The essential point, however, is that "in satire, irony is militant"[2]. This "militant irony" (or sarcasm) often professes to approve the very things the satirist actually wishes to attack. Prelude | Prelude At a glance: Author: Katherine Mansfield Beauchamp First Published: 1917 Type of Plot: Psychological Time of Work: The early twentieth century Setting: New Zealand Principal Characters: Linda Burnell, Stanley Burnell, Isabel, Kezia, Lottie, Mrs. Fairchild, Beryl Fairchild Genres: Psychological fiction, Short fiction Subjects: Family or family life, Time Houses, mansions, or manors Locales: New Zealand The Story “Prelude” describes a move that the Burnell family makes from one house to another. With most of their possessions already in transit, the Burnell women are in a buggy that is packed so tightly that there is no room for Lottie and Kezia. Mrs. Fairchild decides to leave the children with a neighbor until they can be brought later by the grocery man in his wagon. For Kezia and Lottie, the journey to the new house begins at night when everything familiar is left behind, and the carriage rattles into unknown country and along new roads and steep hills, down into bushy valleys and through wide shallow rivers. As they reach the great new house, it appears to Kezia as a soft white bulk stretched on a green garden. When they enter the house, Kezia's lamp reveals wallpaper covered with flying parrots. The dining room has a fireplace, and this center is occupied by the family. The windows are bare but, by the next morning, Beryl will have hung red serge curtains. From this point on, there is a careful room-by-room description of the house. There are four bedrooms upstairs. The servants sleep downstairs in rooms just behind the kitchen. From the windows of the kitchen it is possible to see the washhouse and scullery. The nursery has a fireplace and a table where the children have their meals. The drawing room is described after it has been put in order. As Beryl and Mrs. Fairchild establish daily routines, there emerges a complete floor plan of the house and yards. The windows and the views from them orient the house to the garden and to the light of the sun and the moon. Packing cases disappear, beds are made, pictures are hung, the kitchen is made neat, and everything is put in pairs and on shelves. Daily life is organized into patterns. Plans, also, are made: Mrs. Fairchild will make jam in the autumn; Stanley speaks of bringing men home from the office for Saturday lunch and tennis. The children are sent to play in the garden, their play becoming an imitation of life in the house, but that play is only a prelude to their experience when they leave the garden and go down to the creek, for the garden, which is detailed with as much care as the house, is the prelude to the dark bush that lies beyond it. Kezia explores the well-laid-out, neatly arranged flowers and orchards, always aware of what lies beyond, of what is on the other side of the drive, the dark trees and strange bushes, the frightening side. Driving through the bush at sunset, Stanley is overcome with panic that does not subside until he has been reassured by the sound of Linda's voice that everything is in order. It is in Linda that the two realities find accommodation, life seen as a necessary prelude to death. Although it is not stated in the story that Linda is pregnant, there is a suggestion that she either is or soon will be. Stanley's gift of oysters, which Linda puts aside, is recalled when the servant girl reads in her dream book that a party in a family way should avoid eating a present of shellfish. Removed, unconcerned in the caring for the children and the household, Linda's one function seems to be a creative one. While her mother and sister busily put the household into order and tend to the children, Linda is most often apart, alone in her room, alone in the garden, away from the dinner table when the family is eating, at the end of the drawing room when Beryl and Stanley play cribbage. Mrs. Fairchild and Beryl dress conventionally, but Linda does not dress as the other women do. Instead, she is draped in a shawl or a blanket. The romantic aura thrown about Linda suggests another aspect of the feminine mystique bound up in birth-giving, from which arises the shadowy figure of the mother-goddess who is intimately connected with the moon and the earth. Stanley, on the other hand, is identified with the sun. On the first morning in the new house, he stands in the exact center of a square of sunlight. This initial identification takes on greater proportions as the household comes to life and everything revolves around him and the urgency of his departure. The horse and buggy must be readied; he must make his daily journey, timed with the appearance and disappearance of the sun in the sky. All day, the activities of the house will prepare for his return, and when he comes home, everything is bathed in bright, metallic light. Themes and Meanings Essentially, “Prelude” is about time and place as they affect a single family. There is the time that is measured by the clock and to which the characters respond with daily routines; there is the time of a larger order, that of generations in history; there is time in an even larger, grander sense, the time of nature, of the movement of the planets through the heavens, rotating about the sun. A corresponding sense of place is achieved as the family moves through prescribed paths and areas. The family moves from one house to another, from city to country; the characters move from house to garden and back again into the house; they move from family rooms to private rooms, and finally they move from reality to dream to fantasy in the innermost circle of all. Time and place are parallel. The personal time that governs daily activities is ordered by clock time, which, in turn, corresponds with the movement of the earth around the sun. The planetary motions suggest that larger order of historical time made parallel with the generations of the family delineated in all its tenses, past, present, and future. An absolute time transcends planetary motions, extending beyond the finalities of life and death, and accounts for the individual's attempts to impose structure, order, and meaning on life, to escape the narrow boundaries imposed by life to freer realms of death, to overcome the restrictions imposed by society. Such is the closely woven complex of relationships in “Prelude” that at any specific moment in time, a larger construct of meaning can be derived. Readers of this story find themselves caught up in these various aspects of time. They see a family for the calendar space of seven days; they become familiar with daily routines that measure time like a clock. They see the years of the past merge in the present moment so that the future is always on the point of becoming one with the present, and sometimes does. The child becomes mother and the mother becomes child. Generation is followed by generation in one unbroken sequence. The century plant is coming into bloom again; in another century it will bloom again as it has bloomed in the past. The universe spins on its axis; the planets move about the sun, eternally, through endless space at incredible rates as the sun rises and sets. However, all the different times are simultaneous and exist as one in the human mind. Within the interior regions of the mind, themes are developed. Human concerns are presented: problems of human existences, meanings of life and death. People respond in different ways. Some accept life without question and seek only to achieve order and control over the chaos of living; the questions of these people concern operational means, the design of routine. Stanley is an example. Life, for him, is a matter of regulating daily routines. His is a conventional notion of the well-ordered life. However, Stanley is both man and child, the “master” of the house and the object of the care and responsibility of the members of the household. That there is something wrong with his simplified notion of living is suggested by the panic he experiences when he approaches the house at night and the anxiety he feels in the morning before work. In contrast, Linda accepts nothing, neither the principles of life nor her role nor Stanley, as the answer to larger problems. Her concept of life is broad. It extends to include all things, even the minute, inanimate objects that she invests with her own mobility and awareness in much the same way that the mother gives life to the children that she bears unwillingly. Her life revolves around the more fundamental question of the conflict between the will to survive that is part of the human makeup and the equally strong drive and need for death. Style and Technique To the inexperienced reader of Katherine Mansfield's stories, it must seem that nothing of any significance ever happens. Plot, as one used to know it and still finds it in occasional fiction, has disappeared. The old plot line that could be charted—rising action, climax, falling action—has given way to a line that does not rise very much and then stops somewhere and remains hovering. In contrast to the traditional emphasis on what happens, Mansfield's stories emphasize why it happens, which is an altogether different thing. In a story such as “Prelude,” details do more than set the scene; objects, characters, and incidents and their positions make a tangential point; nothing is apparent, everything is implied. With an in medias res beginning, there is no formal introduction, no exposition, no particular setting of scene. Plunged immediately into a story, without time to accommodate to a new situation, readers are thrown into an imbalance that they must immediately work to set straight, and they have no bearings except those that the story provides. Once in a Mansfield story, readers are moved through a series of incidents that are no more than incidents until relationships are discovered. Ordinarily, relationships are revealed through details that are charged with symbolic significance, image patterns that move to metaphoric levels, and symbolic actions. Details, properly chosen, provide the texture of an experience; sense data ground readers in the concrete, convincing them of the reality of a scene. In her stories, Mansfield causes readers to become immersed in the sensory, invoking all five senses to provide immediacy and intensity. Mansfield's symbols emerge from the story itself; they are formed from the natural materials that create the texture of the experience. Thus, the juxtaposition of Kezia with both Linda and Mrs. Fairchild forms a strong symbolic relationship. So close are the affinities between Kezia and Linda that at times it is possible to see Kezia as an apparition of the past, Linda as child. Their fantasies and dreams are interchangeable. Their common fears and love of Mrs. Fairchild unite them. It is around Kezia and her confrontation with death that a major part of the story revolves. After Pat, the manservant, kills the duck that will be used for dinner, Kezia is first thrilled by the sight of blood, and then she is appalled. She rushes at Pat, putting her arms around his legs and screaming to him to put the duck's head back on his body. That Kezia comes to a similar intuitive knowledge of life and death as Linda is made clear at the end of the story when Kezia tiptoes away from the mirror in the same way that Linda had earlier turned her head as she passed the mirror. The Woman at the Store | The Woman at the Store At a glance: Author: Katherine Mansfield Beauchamp First Published: 1912 Type of Plot: Psychological Time of Work: About 1908 Setting: The bush country in New Zealand Principal Characters: Jo, The narrator, The woman, Else, Jim Genres: Psychological fiction, Short fiction Subjects: Travelling or travellers, Murder or homicide, Rural or country life, Loneliness, New Zealand or New Zealanders Locales: New Zealand The Story Three travelers have been caravanning for more than a month in a remote region of the North Island of New Zealand, a wild Maori country: Jim (a guide who knows the environs), the female narrator, and her dapper brother Jo. The heat has been awful, and one of their horses has developed an open belly-sore from carrying the pack. All have traveled in silence throughout the day. They anticipate reaching a “store” in this wild land, a “whare,” or home that houses a storehouse of goods to supply wayfarers and that includes a pasture for the horses. Jim has been teasing the two about this stopover; it is run, he promises, by a friend generous with his whiskey, and he also speaks of the man's blue-eyed, blond wife, who is generous with her favors. At sundown, they reach the whare, and all is not as cheerful as has been represented. The mistress of the store looks scarcely better than an ugly hag; she is skinny, with red, pulpy hands; her front teeth are missing, her yellow hair is wild and skimpy, and she is dressed in little better than rags. She carries a rifle and is accompanied by a scraggly, undersized, five-year-old daughter and a yellow, mangy dog. She claims that her husband has been gone for the past month “shearin’,” veers wildly in mood, and appears to the visitors to be “a bit off ’er dot,” somewhat unhinged from being too much alone in such a disreputable setting. After some haggling, the travelers are permitted to stop over. She fetches some liniment for the horse and sends food down to the tent that Jim has set up in the paddock. While Jim is working and the narrator bathes in the stream, Jo, the boisterous singer and ladies’ man, “smartens” himself for a visit to the woman at the store. She had once been a pretty barmaid on the West Coast, Jim tells them, and she bragged at having known “one hundred and twenty-five different ways of kissing.” Despite her moods and her tawdry looks, Jo is determined to flirt and to venture. “Dang it! She’ll look better by night light—at any rate, my buck, she's female flesh!” He returns to her whare while the others dine. While Jo is gone, the woman's child brings some food, and, though very young, reveals that she loves to draw pictures of almost any kind of scene. Jo returns with a whiskey bottle; he has induced the woman to play hostess to the little party, and they all return to the whare. The adults become slightly inebriated, the child threatens to draw forbidden pictures, and Jo and the woman become more brazenly flirtatious. When a violent thunderstorm ensues, the woman suggests that they all sleep at the house—Jim, the narrator, and the daughter in the store, Jo in the living room, and herself in the bedroom, close by. All are drunk and laughing as they retire. From their uncomfortable place in the storehouse, surrounded by pickles, potatoes, strings of onions, and half-hams dangling from the ceiling, they can hear Jo rather noisily sneaking into the woman's bedroom. The disgruntled child finally draws for her companions in the store a picture her mother has forbidden her to draft: It reveals the woman shooting her husband with the rifle and then digging a hole in which to bury him. Jim and the narrator are struck speechless. They cannot sleep that night and hasten on their way early the next morning. The narrator laments for her “poor brother.” As they are leaving, Jo appears briefly to motion them on; he will stay a bit and catch up with them later. The meager caravan, now minus its dapper gentleman, moves out of sight. Themes and Meanings “The Woman at the Store” was composed in 1911, when its author was barely more than twenty-one; together with two other tales (“Ole Underwood” and “Millie”), it treats New Zealand scenes and introduces offstage violence to obtain its effect. The repulsive but rather hilarious drinking party abruptly comes to an end when the news of the woman's murder of her “missing” husband is revealed by the small child. At a stroke, the story's meanings are completely turned around. At first, the reader is induced to believe that this is a unique (if somewhat sordid) tale of the wilds— remote, unusual, worthy of being carefully recorded by the narrator. Slowly it becomes clear, however, that, far from being an atypical travelogue, it retells instead “the same old story,” albeit askew and in grotesque parody: the dapper and brazen male flirting with and seducing the innocent maid. Then, with a last twist and turn, the author reveals that the woman is quite capable of giving as good as she gets, and the implicit irony becomes evident: The reader is left to contemplate a savage act quite typical of civilization; after all, Greek tragedy has often portrayed family feuds and parricide; one need not travel into the bush to find barbarism, for it is not the Maori tribes that need be feared, but a lonely, bedraggled woman and a smart, egoistic gentleman caller. Moreover, beneath the glib surface lies the psychological portrayal of loneliness and entrapment. The buxom barmaid has been captured by love, transported to the wilderness, and virtually abandoned by a husband who was always on the run. He often left her for days, even weeks, only to return, demanding a kiss: “Sometimes I’d turn a bit nasty, and then ’e’d go off again, and if I took it all right, ’e’d wait till ’e could twist me round ’is finger, then ’e’d say, ’Well, so long, I’m off.’” Worst of all was her complete transformation. In six years, she has been translated from civilization to isolation, from good looks to ugliness, from sanity to near madness. She has had one child and four miscarriages. Incessantly she reflects on her intolerable life and her intolerable husband: “You’ve broken my spirit and spoiled my looks, and wot for—that's wot I’m driving at.” Again and again, over and over, “I ’ear them two words knockin’ inside me all the time—’Wot for!’” That “wot for” is ultimately a question directed to the universe: What is it all about? Why are human beings driven by whim and passion into impossible situations? In murdering her husband, she has at least initiated some action against a cruel force in the world, but she remains caught in its web. Indeed, her fling with the passing Jo is in one sense a refreshment from the cruel grind of her life, but in another, it is merely the reenactment of the servitude she had endured at the hands of her husband. Ironically, the woman at the store continues in a hopeless round, for she is at once barbarian and citizen, rebel and victim. In a miserable little oasis in the wild, amid a plentitude of stores, she has somehow—maddeningly, incomprehensibly—frittered her own small storehouse away. Style and Technique “The Woman at the Store” is one of Katherine Mansfield's early stories and does not reveal many of the features of her later great tales: extreme subtlety, indirection, tenuous but magical symbolism, impersonation of characters, total mastery of detail and of voice. It is, on the contrary, a straight piece of flatly narrated realism. The narrator herself and Jim are given virtually no personality; all is subsumed by the surface details of travel and encounter with the woman, related with nearly journalistic precision. Indeed, one powerful effect in the tale is achieved when the two learn that the woman is a murderer; understatement prevails, and the characters react almost not at all, expressing no feelings whatsoever. However, it is to be inferred that their response is considerable; Mansfield's employment of indirection here is quite effective. Best of all, stylistically, are touches of tone and color and atmosphere that presage the coming of a master of the twentieth century short story. Often Mansfield's choice of words is exquisitely appropriate, and her effects are accomplished with the seemingly easy hand of the professional. Such achievement, for example, is clearly evident even in the story's opening paragraph: All that day the heat was terrible. The wind blew close to the ground—it rooted among the tussock grass, slithered along the road, so that the white pumice dust swirled in our faces, settled and sifted over us like a dry-skin itching for growth on our bodies. The horses stumbled along, coughing and chuffing. The story is a masterful display, a surprising performance by a very talented young beginner.