Area of study notes

advertisement

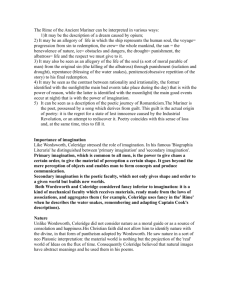

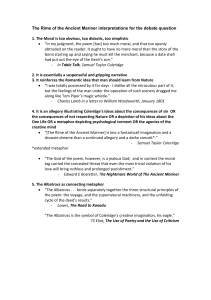

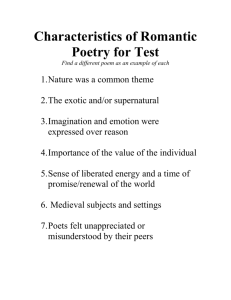

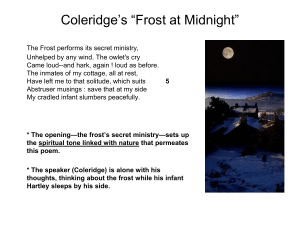

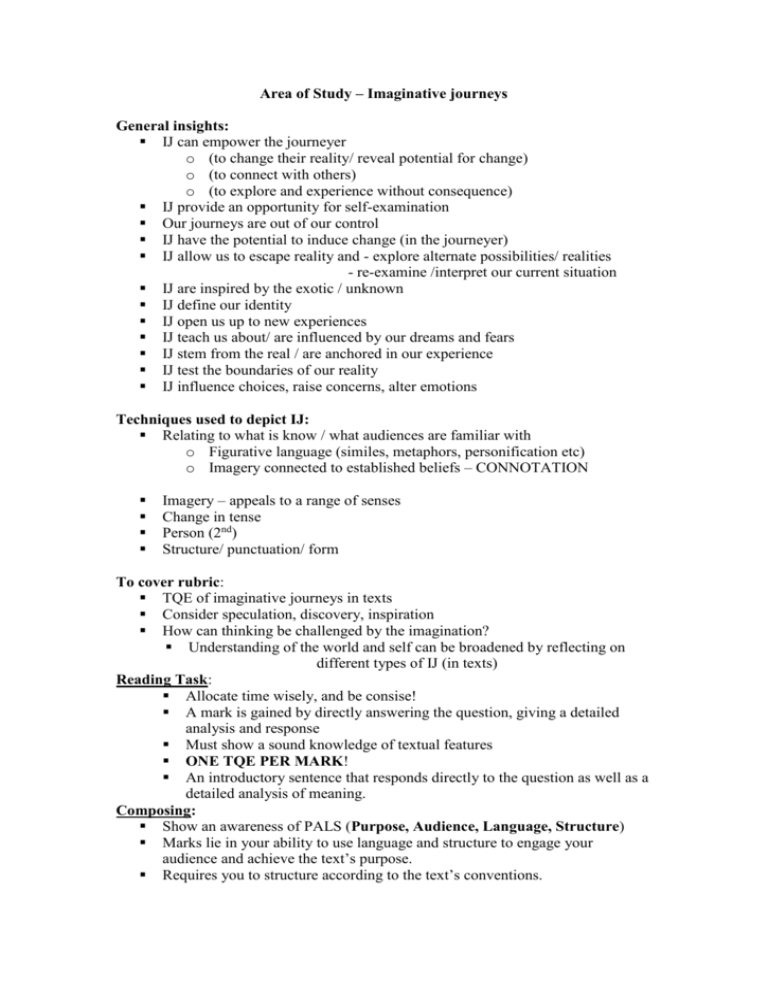

Area of Study – Imaginative journeys General insights: IJ can empower the journeyer o (to change their reality/ reveal potential for change) o (to connect with others) o (to explore and experience without consequence) IJ provide an opportunity for self-examination Our journeys are out of our control IJ have the potential to induce change (in the journeyer) IJ allow us to escape reality and - explore alternate possibilities/ realities - re-examine /interpret our current situation IJ are inspired by the exotic / unknown IJ define our identity IJ open us up to new experiences IJ teach us about/ are influenced by our dreams and fears IJ stem from the real / are anchored in our experience IJ test the boundaries of our reality IJ influence choices, raise concerns, alter emotions Techniques used to depict IJ: Relating to what is know / what audiences are familiar with o Figurative language (similes, metaphors, personification etc) o Imagery connected to established beliefs – CONNOTATION Imagery – appeals to a range of senses Change in tense Person (2nd) Structure/ punctuation/ form To cover rubric: TQE of imaginative journeys in texts Consider speculation, discovery, inspiration How can thinking be challenged by the imagination? Understanding of the world and self can be broadened by reflecting on different types of IJ (in texts) Reading Task: Allocate time wisely, and be consise! A mark is gained by directly answering the question, giving a detailed analysis and response Must show a sound knowledge of textual features ONE TQE PER MARK! An introductory sentence that responds directly to the question as well as a detailed analysis of meaning. Composing: Show an awareness of PALS (Purpose, Audience, Language, Structure) Marks lie in your ability to use language and structure to engage your audience and achieve the text’s purpose. Requires you to structure according to the text’s conventions. This Lime Tree Bower My Prison (1797) In Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s poem This Lime Tree Bower My Prison the metaphor of the prison sets the scene for an escape, and it is Coleridge’s imagination that transports him from the reality he finds himself trapped in, as it allows him to share his friends’ experiences as they walk without him. The text uses extensive imagery of the natural world to convey the intensity of his imaginative journey to the responder. The three stanzas take us along a physical landscape and an emotional one. Coleridge also uses the motif of light to describe the change from his dark mood “The roaring dell, o’erwooded, narrow, deep/ And only speckled by the mid-day sun”, through to uplifting images of the “glorious sun”, the “yellow light”, the “dappling sunshine”, and the “mighty orb’s dilated glory”. The second stanza culminates with his perception of the magnificence of the “Almighty Spirit”. From this revelation “a delight comes sudden on [his] heart, and [he] is glad as he himself were there”. He gains a new appreciation of his “little lime tree bower” and his perspective changes. He no sees himself longer in prison but amongst “much that has soothed him”. This marks a change in his perception of nature and he realises that “nature ne’er deserts the wise and pure”. “Tis well to be bereft of promised good, that we may contemplate with lively joy the joys we cannot share”. In other words, he explains that being refused a pleasure will lead to a greater appreciation of that pleasure. The poem concludes with the journeyer shifting his thoughts back a new empathy for his friend symbolised in the rook that he sees at dusk. His magical description of how it “vanishes in light” as it passes between him and the setting sun once again gives it spiritual qualities, and Coleridge blesses it, envisioning Charles too watching that very bird pass before the sun. Links to other texts: Frost at Midnight (1798) The concept of using his imagination to escape from his limited reality is common in much of Coleridge’s poetry. In Frost At Midnight, he is prompted to recall his childhood, which he describes in a negative tone. He explains that he was forever imagining an escape from his studies, and longed for a stranger to take him away on an adventure. Coleridge feels that since his childhood lacked excitement, he is obliged to build a happier childhood for his newborn son. He speculates that his son “shalt wander like a breeze/ By lakes and sandy shores” and that God “shalt mould his spirit”. Whether this is a future reality for his son or not, the inspiration that Coleridge attains from his speculative vision sees him determined and positive. His imagery of the frost is transformed, from devious and sinister (“performs its secret ministry”) to beautiful and luminous (“…Silent icicles/ Quietly shining to the quiet moon.”). - Conversation poem that eventually broadens his own understanding of the world. “The Frost performs its secret ministry” (l.1) Here Coleridge establishes an air of a magical, quasi-religious process at work in the simple natural act of the frost falling outside. The line also implies a strong energy at work – despite this sense of energy, it is silence that is to be the most overwhelming sense in the poem. “Unhelped by any wind.” (l.2) The feeling of extreme stillness is built up, broken only by the cry of the owlet – a cry which Coleridge uses to draw the reader into the poem, with the direct address of “hark, again!” (l.3) The condition that dominates the poem at this point is that of extreme quiet and stillness: ‘Tis calm indeed! so calm, that it disturbs/ And vexes meditation with its strange/ And extreme silentness’. The notion of a calm so great that it disturbs is not only a paradox, but seems to overturn the idea that Coleridge is in a situation of “a solitude, which suits abstruser musings” (ll.5-6). If anything, the calm seems to be disturbing him – and this is the central paradox of the poem: the idea of quiet stillness-in-the-midst-of-movement or of movement-in-the-midst-of-quiet stillness. The best example of this paradox is Coleridge’s own active mind in the midst of, and set off by, the extreme quiet. The silence itself is the provoker of meditation. The whole poem is a fine balance of slumberous stillness and super-sensitive awareness. Coleridge’s mind at this point moves back into the cottage and focuses very closely on one object – a small piece of ashy film fluttering in the grate of his fire. This fluttering film is the central symbol of the whole poem, for by now we see the poet’s mind as “the sole unquiet thing. The notion of the play of thought triggers a childhood memory (a time of using literal toys). The memory triggered is of a similar incident in childhood when he was staring at another such film on a fire grate while away at school. This time the film is reported as having been visible against “bars” (l.25) - a prison-like image. This prison image is continued in the later description of the city itself (“the great city, pent” l.52) when Coleridge recalls his schoolboy self away from home daydreaming (a dreamwithin-dream) of his birthplace. These films of ash on the grate were called “strangers” because they were supposed to portend the arrival of an absent friend. The memory of the “stranger” that he had gazed upon in the schoolroom when a child makes Coleridge recall the wish that had accompanied that daydream - namely, that a stranger would indeed arrive - a townsman or relative from his birthplace who would arrive to take him back, to rescue him from the “great city, pent.” At the end of this movement of the mind into the past, Coleridge now takes his musing into the future - the past movement of the poem is balanced by this forward movement into the potential future of his own son, Hartley, sleeping by his side in the present moment of the poem. Coleridge first stresses the child’s breathing as he sleeps and as he does, we realise that the regular in-out movement of breath echoes the rhythm of the poem itself: Dear Babe, that sleepest cradled by my side, Whose gentle breathings, heard in this deep calm, Fill up the interspersed vacancies And momentary pauses of the thought! (ll.44-47) The idea that his son will be reared not in the “great city, pent”, but amid the lakes and mountains is a great source of joy for Coleridge - a typically Romantic position. “... it thrills my heart ...................................... ........... that.......... .................................. ... thou, my babe! shalt wander like a breeze By lakes and sandy shores and, beneath the crags Of ancient mountain, and beneath the clouds, Which image in their bulk both lakes and shores And mountain crags” These lines pick up two crucial Romantic themes: that the unity of humans with nature brings “Joy” that there is an essential unity within all nature itself (Note how the mountains and lakes are reflected in the clouds). A third Romantic theme occurs in the immediately following lines, in which the systolic movement reaches out to Coleridge’s god and raises the theme of the essential unity of humanity, God and Nature - with Nature itself being seen as the language of God: ... so shalt thou see and hear The lovely shapes and sounds intelligible Of that eternal language, which thy God Utters, who from eternity doth teach Himself in all, an all things in himself In this - and again, this is typically Romantic notion - the poet himself is like a god. This poet in this setting (the cottage) has also “(taught) Himself in all, and all things in himself.” The poet sees God’s works manifested quite specifically as a “language” (l.60), just as his own work of creation - this poem - is manifested as language. Note that the return to the hush of the beginning fuses all time in the moment of the poem itself - and also, as we can see through the sound structure of the last two lines, in the “I”, in the figure of the solitary poet himself. “It thrills my heart […] to […] think that thou shalt learn far other lore/ And in far other scenes!” Links to other texts: For all stimulus booklet texts, see summary sheets written by the class. The Wind in the Willows (excerpt) Kenneth Grahame’s Wind in the Willows excerpt sees two characters, Rat and Toad, caught up in a battle between reason and impulse, head and heart, each intending to convince a third friend, Mole, that they are right. The text makes clear use of allegory in its representation of the age-old struggle between common sense and the imagination. The personification of Toad as a romantic, rather excitable creature gives him archetypal features: he fits the mould of ‘the dreamer’, who has in this case envisioned a pleasant escape for himself and his friends, and acted on these impulses by preparing for the trip without their consent. He describes his imagined journey as “real life…The open road, the dusty highway, the heath… the hedgerows, the rolling downs! The whole world before you… and a horizon that’s always changing!” The composer’s use of natural imagery and expressive punctuation in this statement help to convince the responder of the attractiveness of this vision. Toad’s imaginative journey allows him to believe that his “little cart” will help him escape the routine and monotony of everyday life, and experience “real life”. It is up to the responder to see the irony in this proclamation, however, as Toad’s “real life” exists (so far) only in his imagination. It can also be inferred that there is a slightly less literal meaning to the text. I believe that the excerpt is an extended metaphor which addresses an internal struggle between sense and spontaneity in the composer. Grahame examines his own romantic versus logical motives through his characterisation of Toad and Rat, with Mole’s undecided and somewhat blank character perhaps representing his own. The blindness usually associated with moles emphasises his indecisive nature. Links to other texts: ORM 1 – Imagine Imagine is a picture book composed by Alison Lester and published in Sydney in 1989. The text follows two children through an imaginative learning experience in which they are inspired to dream up various natural environments and the fauna that inhabits them. Readers, as well as following the characters on their journey, are alerted to the way in which the imaginative process works. In this text, the composer explores the power of the imagination as a learning tool and as an escape from one’s immediate surroundings to an alternate world full of possibilities. As the text is aimed at child audiences, the composer is able to teach readers about how their own imagination works and about the environments she transports them to in a colourful, entertaining way. Repetitive use of the word “imagine” (in the title and in the patches of text) prepares readers for the imaginative journey that is to follow. Repetition of the word “imagine” emphasises the purpose of the story, and alerts readers to the imaginative process that is being undertaken by themselves and the characters. The layout of the text always sees the word imagine on its own – it never shares a line with another word. This too helps to highlight the importance of the imagination in the story. The composition of the text, with an image of the characters playing makebelieve at home succeeded by a double-page image of their imagined world demonstrates the process that is taking place in the characters’ minds. Once again, layout is used to stress the imaginative process being undertaken. Readers are led to understand the manner in which inspiration and speculation work, as it is plainly put before them in the form of the characters’ adventure. They are then encouraged to examine the process being undertaken within their own minds: they too are hearing the description of each location during the verse, creating it in their heads and finally comparing it with the illustrations on the following page. Readers are therefore encouraged to acknowledge their active involvement in the process of imagination. The written verse describing the location imagined by the characters provides an opportunity for readers to imagine the location themselves before turning the page and seeing the illustration. Imagery is used (“where butterflies drift, and jaguars prowl”) as well as alliteration (“hermit-crabs hide”, “Killer-whales crash”), onomatopoeia (“crash”, “gobble”, “smash”, “gnash”), and rhyme (“feed” and “stampede”, “crash” and “gnash”, “prowl” and “howl”). Each of these techniques combine in the reading of the text to provoke an exciting, living image of the habitat being described. On each of the illustrated pages where the imaginings of the characters are presented, long lists of names of all the different animal species depicted in the illustration sweep around the outside of the page. These work as evidence of an imaginative journey because the reader realises that a scene involving all of these animals simultaneously is unrealistic. Lists are used to emphasise the number of different animals, as well as provoking a sense of exoticness. Layout is also used: the lists encircle the image so that the reader must turn the book to read them, giving the image another apparent dimension. This works to involve the reader further in the environment. The lists also help to teach the names of all the animals to the reader. For the reader, the journey that the characters undertake is a valuable learning experience. Not only does the text provide readers with the opportunity to learn about numerous global ecosystems and the creatures that inhabit them, but also clarify what it means to imagine. The consequence of the imaginative journey for the characters is complete satisfaction, to the extent that at the end of their adventure they are happy to be safe and warm at home, and have no need to imagine any more. The reader too shares in this satisfaction, and the final image of the characters peering through the windows of their warm little cottage is a pleasing ending to the story. In this text, the imaginative journey has been used as a medium through which readers are able to learn about the imaginative process itself. Upon being presented with an image of children playing, succeeded by an image of their imagined location, the reader is able to connect the two images as the one experience, before actively partaking on an imaginative journey themselves, while still being aware of the difference between their imagined world and their reality. This text shows us that an imaginative journey, through literature, is a collaboration of the composer and the reader. The composer’s description of the journey works to stimulate an image in the reader’s mind, but each text requires active participation on the reader’s part as well. The imaginative journey, therefore, provides an opportunity for responders and composers to come together in each reading of the text. Links to other texts: ORM 2 – Clairvoyance La Clairvoyance, by Rene Magritte, is a self portrait in which Magritte depicts the artistic process. In the painting, the artist is shown watching an egg yet painting a bird. He uses two images from the natural world, the egg and bird, to symbolise change and growth, and the textual gap between these symbols must be actively filled in by the responder, involving them in the imaginative process. The bird on Magritte’s canvas has outstretched wings, indicating mid-flight. The connotations of liberty that this symbol brings contrast sharply with the confined form of the egg. This text provides scope for Magritte to examine his role as an artist. He demonstrates the imaginative process in looking beyond reality to speculate about the future or reflect on the past. He also explores the power of connotation. He ponders on how much of what he sees is actually there and how much is fabricated or amplified into something more dramatic. It is clear that the freedom of choice and movement that the bird represents are contrasted by the still, sombre and uninteresting depiction of the artist in his room. The egg in this text can be seen to have metaphorical significance: Magritte seems to be suggesting that the imagination can set you free of the confines of your egg, which in this case is representative of reality. While Magritte’s dream of freedom and flight are inspired by the egg, he still acknowledges the fact that power of the imagination can be dangerous and deluding. He shows that while speculation can allow an escape from reality, it remains only a figure of the imagination and ultimately his bird is a two dimensional picture on canvass. Links to other texts: Techniques Lime Tree Bower Religious Metaphor/ Imagery “mighty “Secret orb’s dilated ministry of glory” frost” capital N for “Nature” “Love and Beauty” Natural Imagery “The roaring dell, o’erwooded, narrow, deep, and only speckled by the mid-day sun” Images/ Graphics Allegory Frost At Midnight Clairvo yance “Shalt wander like a breeze By lakes and sandy shores, beneath the crags of aincient mountain… ” Imagine “Where butterflies drift, and jaguars prowl” Yes Wind In The Willows Road Not Taken Text 7 Ivory Trail Describes a place acting with an “irresistibl e force” that will make traveller “blessed and altered” Minorettes and pyramids connote to Eastern/ exotic/ ancient religion “The heath, the hedgerows, the rolling downs” Yes Yes Animals present the battle between head and heart – sense and sensibility Yes! See earlier Layout Moral Figurative Language “Nature ne’er deserts the wise and pure. No plot so narrow…” “Tis well to be bereft of promised good” “I am glad “Frost as I myself performs its The Ivory Trail presented with a sense of perspective so that a trail-like effect is produced. It is better to take the path less travelled by- you will be more content in the end. Onomatopo eia, rhyme, “I’m going to make an Fork in road is were there”, “This lime tree bower my prison” secret ministry”, “my swimming book” Insights Lime Tree Bower Frost At Midnight Clairvoyan ce Imagine Reveal potential for change Coleridge is inspired by his journey to reinterpret his situation and to gain a greater appreciation of the nature around him. Memories of his own childhood inspire him to build a more romantic future for his son. Depicted journey speculates about the future of the egg – depicts the changes that will occur. In depicting the imaginative process, the composer demonstrate s ways in in which we are able to escape from reality. alliteration “Arctic hares dash, and killer whales crash” animal out of you, my boy”, “The whole world before you, and a horizon that’s always changing” Wind In The Willows “I’ll make an animal out of you” – Toad imagines an exciting new life, “embodie d in that little cart” metaphor for choices in life. Road Not Taken Text 7 Ivory Trail Speculates about the potential difference a different path at a fork could have on the outcome of his life. Return “Blessed and altered” Responder s are inspired by the cover to buy the book and partake on this exotic adventure – allowing them to escape from their Explore and experience without consequence He is able to participate, in a sense, in the walk using his imagination Explores his past and compares it with alternatives for the future. Depicts an escape from reality Escapes from his ‘prison’ using his imagination – leads him to discover that he was never trapped in the first place The “extreme silentness” allows him to journey between past, present, future. Boyhood – escape from school. the imagination can set you free of the confines of your egg, which in this case is representati ve of reality Stem from Journey Inspired by Yes Children from story are able to learn and experience through their imagination Toad has not fully considered the consequen ces of his imagined journey – his ‘real life’ exists only in his imag. Here the imagination allows the characters to alter their perception of the game they are playing, making it more colourful and dramatic. Journeys Toad believes the journey will allow the friends to escape the monotony of everyday life. IJ allows composer to speculate about both paths before committin g. Text claims that people (unconsci ously) imagine a place where they will be blessed and altered. In ?? If there imagining, is a need the to be composer altered, is able to then put off the perhaps choice. everone everywher e is always searching for a better reality. Metaphor reality. See above See above Speculativ the real – journeys of inspiration Selfexamination Re-interpret reality inspired by a path he had previously walked many times. Inspired by the bower around him, the sun, sky, rook. Coleridge learns that he is able to find divine inspiration wherever he finds nature. Gains a deeper appreciation of his ‘little lime tree bower’ Speculation? Imagines the path the silence, the “stranger” on the grate, by his own past. inspired by the rhyme and the toys they are playing with. Magritte examines his active role as an artist in the inspiration process. is inspired by a big decision in life. Composer is perhaps weighing up his own sense vs. sensibility After much playing the children realise that what they want most is simply to be at home. “It thrills my Speculate heart […] to about what Toad’s perception Composer speculates about the two different outcomes of the decision. Metaphor provides a clearer way to express/ consider the problem. Yes e journey about what the story holds is inspired by the images on the cover Alerts responders to this trend – am I looking to be enlightene d as well? Where is / will I ever See above taken by his friends as they walk and the effect of the journey on Charles Discovery?/ Learning tool? “Nature ne’er…”, “Tis well to be bereft of promised good…” […] think that thou shalt learn far other lore/ And in far other scenes!”, “All seasons shall be sweet to thee”, “Thou […] shalt wander like a breeze” Learns what really matters in life – an appreciation of nature and beauty. will happen to the egg… the textual gap between the symbols must be actively filled in by the responder, involving them in the imaginative process the textual gap between egg and bird must be actively filled in by the responder, involving them in the imaginative process of ‘real life’ is only speculatio n – he cannot forsee the obstacles that lie ahead of the travellers. IJ allows children to learn about the imaginative process as well as the environment s/ habitats find my Genii loci? Composer learns that the road less travelled “made all the difference ” – don’t be a sheep Yes