Microsoft Word version

advertisement

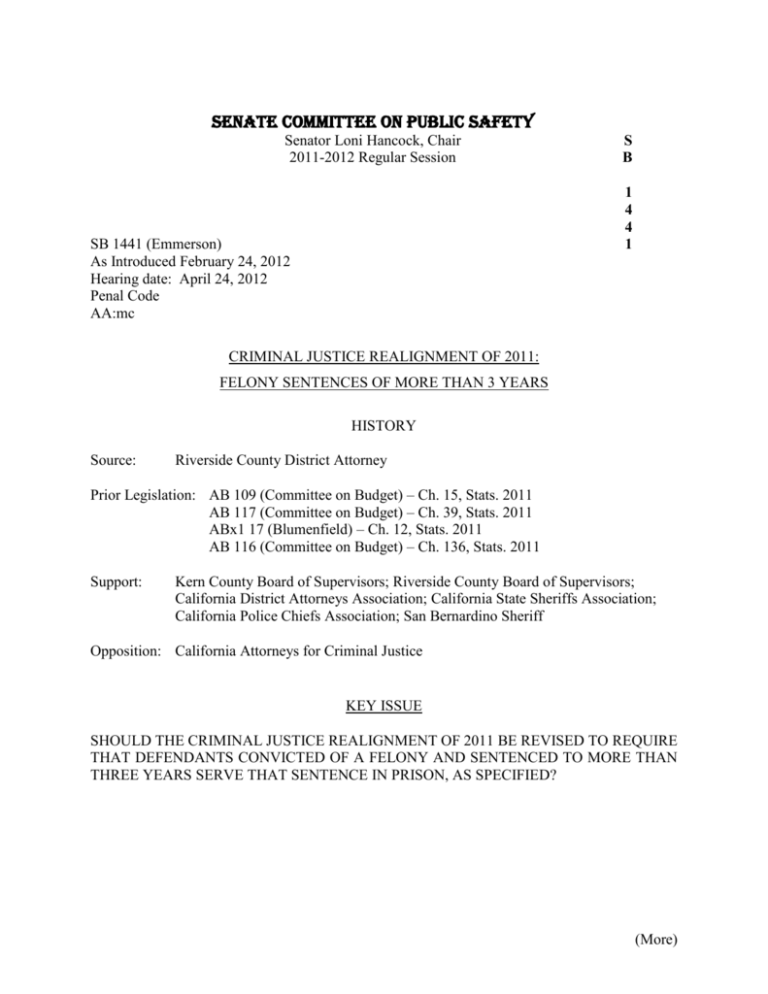

SENATE COMMITTEE ON PUBLIC SAFETY Senator Loni Hancock, Chair 2011-2012 Regular Session S B 1 4 4 1 SB 1441 (Emmerson) As Introduced February 24, 2012 Hearing date: April 24, 2012 Penal Code AA:mc CRIMINAL JUSTICE REALIGNMENT OF 2011: FELONY SENTENCES OF MORE THAN 3 YEARS HISTORY Source: Riverside County District Attorney Prior Legislation: AB 109 (Committee on Budget) – Ch. 15, Stats. 2011 AB 117 (Committee on Budget) – Ch. 39, Stats. 2011 ABx1 17 (Blumenfield) – Ch. 12, Stats. 2011 AB 116 (Committee on Budget) – Ch. 136, Stats. 2011 Support: Kern County Board of Supervisors; Riverside County Board of Supervisors; California District Attorneys Association; California State Sheriffs Association; California Police Chiefs Association; San Bernardino Sheriff Opposition: California Attorneys for Criminal Justice KEY ISSUE SHOULD THE CRIMINAL JUSTICE REALIGNMENT OF 2011 BE REVISED TO REQUIRE THAT DEFENDANTS CONVICTED OF A FELONY AND SENTENCED TO MORE THAN THREE YEARS SERVE THAT SENTENCE IN PRISON, AS SPECIFIED? (More) SB 1441 (Emmerson) Page 2 PURPOSE The purpose of this bill is to revise the criminal justice realignment of 2011 by requiring that defendants convicted of a felony and sentenced to more than three years shall serve that sentence in prison, as specified. Current law generally provides that, for any person sentenced on or after October 1, 2011, certain felonies – those which by their statutory terms specifically so provide – are punishable by a term of imprisonment in a county jail, as specified. (Penal Code § 1170(h).) Current law provides that, notwithstanding this general provision, where a defendant meets any of the following criteria an executed sentence for a felony punishable pursuant to this subdivision shall be served in state prison: The defendant has a prior or current felony conviction for a serious felony described in subdivision (c) of Section 1192.7; The defendant has a prior or current conviction for a violent felony described in subdivision (c) of Section 667.5; The defendant has a prior felony conviction in another jurisdiction for an offense that has all of the elements of a serious felony described in subdivision (c) of Section 1192.7 or a violent felony described in subdivision (c) of Section 667.5; The defendant is required to register as a sex offender, as specified; or The defendant is convicted of a crime and as part of the sentence an enhancement pursuant to Section 186.11 is imposed. (Penal Code § 1170(h)(3).) This bill would amend this provision to provide in addition that where a defendant has been convicted of a felony punishable pursuant to this subdivision and is sentenced to more than three years, the sentence shall be served in state prison, as specified. RECEIVERSHIP/OVERCROWDING CRISIS AGGRAVATION (“ROCA”) In response to the unresolved prison capacity crisis, since early 2007 it has been the policy of the chair of the Senate Committee on Public Safety and the Senate President pro Tem to hold legislative proposals which could further aggravate prison overcrowding through new or expanded felony prosecutions. Under the resulting policy known as “ROCA” (which stands for “Receivership/Overcrowding Crisis Aggravation”), the Committee has held measures which create a new felony, expand the scope or penalty of an existing felony, or otherwise increase the application of a felony in a manner which could exacerbate the prison overcrowding crisis by expanding the availability or length of prison terms (such as extending the statute of limitations for felonies or constricting statutory parole standards). In addition, proposed expansions to the classification of felonies enacted last year by AB 109 (the 2011 Public Safety Realignment) which may be punishable in jail and not prison (Penal Code section 1170(h)) would be subject to ROCA because an offender’s criminal record could make the offender ineligible for jail and (More) SB 1441 (Emmerson) Page 3 therefore subject to state prison. Under these principles, ROCA has been applied as a contentneutral, provisional measure necessary to ensure that the Legislature does not erode progress towards reducing prison overcrowding by passing legislation which could increase the prison population. ROCA will continue until prison overcrowding is resolved. For the last several years, severe overcrowding in California’s prisons has been the focus of evolving and expensive litigation. On June 30, 2005, in a class action lawsuit filed four years earlier, the United States District Court for the Northern District of California established a Receivership to take control of the delivery of medical services to all California state prisoners confined by the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (“CDCR”). In December of 2006, plaintiffs in two federal lawsuits against CDCR sought a court-ordered limit on the prison population pursuant to the federal Prison Litigation Reform Act. On January 12, 2010, a three-judge federal panel issued an order requiring California to reduce its inmate population to 137.5 percent of design capacity -- a reduction at that time of roughly 40,000 inmates -- within two years. The court stayed implementation of its ruling pending the state’s appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court. On May 23, 2011, the United States Supreme Court upheld the decision of the three-judge panel in its entirety, giving California two years from the date of its ruling to reduce its prison population to 137.5 percent of design capacity, subject to the right of the state to seek modifications in appropriate circumstances. Design capacity is the number of inmates a prison can house based on one inmate per cell, single-level bunks in dormitories, and no beds in places not designed for housing. Current design capacity in CDCR’s 33 institutions is 79,650. On January 6, 2012, CDCR announced that California had cut prison overcrowding by more than 11,000 inmates over the last six months, a reduction largely accomplished by the passage of Assembly Bill 109. Under the prisoner-reduction order, the inmate population in California’s 33 prisons must be no more than the following: 167 percent of design capacity by December 27, 2011 (133,016 inmates); 155 percent by June 27, 2012; 147 percent by December 27, 2012; and 137.5 percent by June 27, 2013. The author’s office has been informed that this bill appears to aggravate the prison overcrowding crisis described above under ROCA. COMMENTS 1. Stated Need for This Bill The author states: (More) SB 1441 (Emmerson) Page 4 Under realignment, low-level offenders are being shifted from prisons to local jails. As it stands, approximately 32 counties are faced with overcrowding or court-imposed caps on jail populations. Therefore, the realignment population shift is causing our local jails to be even more over crowed than before. Furthermore, California’s jails were not built or designed to house prisoners for long periods of time. 2. What This Bill Would Do As explained above, this bill would change provisions in the 2011 criminal justice realignment concerning which felonies must be served in prison. Specifically, this bill would widen the category of which executed felony sentences must be served in state prison – not county jail – by providing that sentences of more than 3 years must be served in state prison. Under current law, there is no term-based threshold for which felonies must be served in prison or jail. This bill would result in more felons serving their custodial time in prison. Committee staff is unaware of data estimating the impact of this particular bill on the prison population and the state’s ability to make progress on meeting the reductions ordered by the court in Plata. The overall estimated impact of realignment is noted in a Legislative Analyst’s Office’s February report on realignment: CDCR projects that the average daily prison population will be nearly 11,000 inmates, or 7 percent, lower in 2011-12 than it would have been in the absence of realignment. By 2016-17, the department estimates that the prison population will be lower by nearly 40,000 inmates, or 24 percent, than it otherwise would have been absent the 2011 realignment. By the end of this projection period, the state’s prison system is expected to have about 124,000 inmates. These estimates are consistent with the administration’s original projections regarding the impact of the 2011 realignment on the state prison population.1 3. Background: Felony Sentencing Under the Criminal Justice Realignment of 2011 The “2011 Realignment Legislation Addressing Public Safety” (“criminal justice realignment”) fundamentally altered how convicted felons are handled under California law.2 Under California law operative until October 1, 2011, a felony was a crime punishable by death or imprisonment in state prison.3 Effective October 1, 2011, criminal justice realignment redefined the term The 2012-13 Budget: Refocusing CDCR After The 2011 Realignment, Legislative Analyst’s Office (February 23, 2012.) 2 AB 109 (Committee on Budget) (Ch. 15, Stats. 2011) is the principal measure establishing the 2011 public safety realignment. As noted at the beginning of this analysis, several subsequent measures revised AB 109 and enacted additional provisions relating to certain aspects of realignment. 3 Penal Code § 17. This classification does not affect the ability of the court to suspend execution of a felony sentence and impose conditions of probation where allowable, supervised and performed locally. (See Penal Code § 1203.1.) A misdemeanor is a crime punishable by imprisonment by 6 months or not more than one year. (Penal Code §§ 19 and 19.2.) 1 (More) SB 1441 (Emmerson) Page 5 “felony” to include crimes punishable by imprisonment in a county jail, as specified, depending upon the criminal history of the offender.4 As explained in a January 2012, article describing felony sentencing after realignment: With respect to felony sentencing, it appears the intent of the realignment legislation is merely to change the place where sentences for certain crimes are to be served. The legislation has not changed the basic rules regarding probation eligibility. Courts retain the discretion to place people on probation, unless otherwise specifically prohibited, under the law that existed prior to the realignment legislation. There is no intent to change the basic rules regarding the structure of a felony sentence contained in sections 1170 and 1170.1. Furthermore, there is no change in the length of term or sentencing triad for any crime. Realignment comes into play when the court determines the defendant should not be granted probation, either at the initial sentencing or as a result of a probation violation.5 The confinement changes under criminal justice realignment – that is, modifications to where felons serve their executed felony sentences in custody, either in state prison or in local facilities – apply to persons sentenced on or after October 1, 2011. These changes are not retroactive.6 Criminal justice realignment provides that numerous felonies are punishable by a term of imprisonment in county jail – not prison – unless the crime of conviction or a defendant’s criminal history makes the defendant ineligible for serving their felony sentence in jail.7 This change, contained in subdivision (h) of Penal Code section 1170, applies only to criminal statutes which have been expressly amended to provide for a felony jail term where otherwise allowable.8 4 Penal Code § 17, as amended by Section 228 of AB 109 and Section 6 of ABx1 17. Felony Sentencing After Realignment, J. Richard Couzens, Judge of the Superior Court, County of Placer (Ret.); Tricia A. Bigelow, Presiding Justice, Court of Appeal, 2nd Appellate District, Div. 8, p. 3 (January 2012). (http://www.courts.ca.gov/partners/documents/felony_sentencing.pdf.) 6 Paragraph (6) of subdivision (h) of Section 1170 of the Penal Code, as amended by Sections 27 and 28 of AB 117, and Section 12 of ABx1 17, states: “The sentencing changes made by the act that added this subdivision shall be applied prospectively to any person sentenced on or after October 1, 2011.” With the exception of the role of courts in adjudicating parole violations, which starts on July 1, 2013, the major criminal law provisions of realignment became operative on and after October 1, 2011. (See Section 68 of AB 117 and Section 46 of ABx1 17.) 7 Just like the law prior to realignment about the length of terms, if a term is not specified in the underlying offense the crime shall be punishable by a term of imprisonment for 16 months, or two or three years and, for crimes where the underlying criminal statute specifies the term, the felony shall be punishable by imprisonment for the term described in the underlying offense. (See Penal Code § 18, as amended in Section 230 of AB 109 and Section 7 of ABx1 17, and Penal Code Section 1170(h), as amended by sections 27 and 28 of AB 117.) 8 This feature of criminal justice realignment – that its newly-created felony jail sanction can be applied only to those criminal statutes expressly amended to include a cross-reference authorizing that sanction – largely accounts for the length of AB 109 (663 pages). 5 (More) SB 1441 (Emmerson) Page 6 Certain felons are categorically prohibited from serving an executed felony sentence in county jail. The following persons are statutorily ineligible to serve any executed felony sentence in county jail: The defendant has a prior or current felony conviction for: o a serious felony described in subdivision (c) of Section 1192.7, or o a violent felony described in subdivision (c) of Section 667.5; The defendant has a prior felony conviction in another jurisdiction for an offense that has all the elements of a serious or violent felony in California, as specified; The defendant is required to register as a sex offender; or The defendant is convicted of a crime and as part of the sentence receives an aggravated theft enhancement, as specified.9 For convicted felony offenders subject to confinement in a county jail, courts are authorized to impose the felony sentence to commit a defendant to county jail as follows: For a full term in custody as determined in accordance with the applicable sentencing law. For a term as determined in accordance with the applicable sentencing law, but suspend execution of a concluding portion of the term selected in the court’s discretion, during which time the defendant shall be supervised by the county probation officer in accordance with the terms, conditions, and procedures generally applicable to persons placed on probation, for the remaining unserved portion of the sentence imposed by the court. The period of supervision shall be mandatory, and may not be earlier terminated except by court order. During the period when the defendant is under such supervision, unless in actual custody related to the sentence imposed by the court, the defendant shall be entitled to only actual time credit against the term of imprisonment imposed by the court.10 As noted by Judge Couzens and Justice Bigelow: Sentences imposed under section 1170, subdivision (h)(5)(B), have been characterized as “split” or “blended” sentences because they have both custody and non-custody elements. The length and circumstances of the suspended term are within the court’s discretion; presumably the court could suspend all or only a portion of the sentence. There are many sentencing strategies available to the court, depending on the defendant’s circumstances, hopefully enlightened by a current risk/needs assessment done by the probation department. The following represent just a few of the options available to the court: 9 Penal Code § 1170(h) (3), as amended in Sections 450 and 451 of AB 109, Sections 27 and 28 of AB 117, and Section 12 of ABx1 17. 10 Penal Code § 1170(h) (5), as amended in Section 12 of ABx1 17. (More) SB 1441 (Emmerson) Page 7 The court could impose a term from the triad, suspend a concluding portion of the term and set conditions of supervision. Such an alternative may be appropriate when the time in custody will be relatively short such that the case plan developed at sentencing will be reasonably current when the defendant converts to mandatory supervision. The court could impose a term from the triad, suspend a concluding portion of the term, but reserve jurisdiction to set the conditions of supervision shortly before the defendant is released from custody. Such an alternative may be appropriate when the court realizes that supervision is necessary, but because of a lengthy custody period may want to have a new risk/needs assessment at the time the defendant is ready to be released. Such a strategy will account for the changing nature of defendant’s risk and will make the case plan more relevant to defendant’s actual circumstances at the time he is ready for release. The court could choose to impose a sentence under the provisions of section 1170, subdivision (h)(5)(B), but reserve jurisdiction to set the actual time and conditions of release at a later time. Such a strategy might be appropriate where the court wants to give the defendant encouragement to complete various custody programs and do well in custody, then set relevant terms when the court determines release is appropriate.11 4. Reports of Very Long Jail Felony Sentences Since the enactment of realignment, there have been anecdotal and press reports of very long felony sentences required to be served in county jail. For example: Javier Miranda was arrested last November while driving a truck full of methamphetamine up Interstate 5. After a short trial, he received an 18-year sentence – but he won’t go to prison. Instead, Miranda will serve his time in county jail. The length of Miranda’s sentence is an unusual but not a unique result of prison “realignment.” Counties throughout California are now tasked with housing and rehabilitating prisoners classified as non-serious, non-violent and non-sexual, no matter the length of their sentence in their jail. Before realignment, prisoners like Miranda would likely have faced prison time. ... 11 Felony Sentencing After Realignment, supra fn.4, at p. 8. (More) SB 1441 (Emmerson) Page 8 There is a difference between spending 18, seven or even two years in county jail as opposed to prison. Jails often lack the necessary resources for longer stays, such as medical care and other social services programs that help rehabilitate prisoners. ... Miranda is the first person in Merced County to be handed such a long jail sentence. Merced County Chief Deputy District Attorney Harold Nutt was the prosecutor in Miranda’s case and said the 18 years – four years for the principal charge, 10 for weight of drugs he was transporting (10 kilos), three years for a prior prison term for a similar drug-related offense and one year for a prior prison term – fit the crime. Realignment, he said, took away a hammer that law enforcement once had to hold people accountable. Prison, he said, used to be a real threat to individuals looking to offend and re-offend. Without the option of prison, county jails will increasingly have to bear the burden of long sentences. “This is highly unusual,” he said of Miranda’s 18 years in jail. But, he added, “It wouldn’t be inconceivable to sentence someone to seven or eight years. Realignment changed the way everybody looks at things.” Merced is not the only county that has seen jail sentences of longer than a year. The longest in Contra Costa County so far is five years. In San Bernardino the longest sentence was 10 years, and in Riverside, 14 years. Santa Barbara County jail holds one inmate sentenced to 23 years. Long jail sentences have mostly been in Southern California, said Pazin, who is also president of the California Sheriff’s Association. That area of the state also has the largest population, he noted. How many years of their sentence that these inmates will actually serve behind bars depends on the respective county’s resources and realignment plan. Miranda is going to be in custody in Merced’s jail for at least two years, according to Antoinette Murillo, public information officer for Merced County Corrections Department. He’ll spend another couple of years on electronic monitoring before going under the supervision of probation, she said. Miranda has a U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement hold, she noted, which also might affect what happens to him once he is released from jail. (More) SB 1441 (Emmerson) Page 9 Barely a year into realignment, multi-year sentencing is an unintended consequence of reform, Pazin said. He added that he and his colleagues hope to discuss the possibility of a legislative remedy to the problem with Gov. Jerry Brown in the future. In the meantime, he said, “We are hoping that this won’t become a trend.”12 *************** 12 Realignment Results in Lengthy Jail Sentences, M. Perez, California Health Report (http://www.healthycal. org/archives/8196.)