cardiovascular disease and the workplace

advertisement

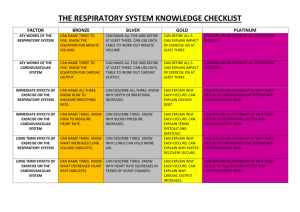

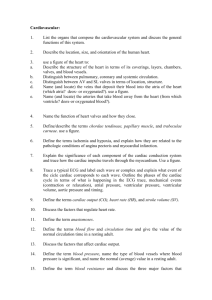

1 Occupational Health and the Heart: Text to accompany slides: 1. Title slide 2. Two important facets of cardiac disease as it relates to health at work. Agents used in the workplace may produce toxic effects manifested as heart disease or dysfunction. Possibly more important, however, is the effect that heart disease (common in Western society) has on the ability to work. Both will be covered in this module. 3. Problems in identifying effects of occupational agents on the heart: a. Endpoints are common in US and Western Europe, so effects of an agent may not be noticed as producing illness above the high baseline rate. b. Cardiac disease has multiple risk factors, some common and under the control of the subject (smoking, obesity and reduced physical activity), some which require intervention (hypertension, hypercholesterolemia). c. Long-latency illness such as heart disease my not be apparent until long after the individual has left the workplace. d. Moreover there are no effects of occupational exposures that have differing manifestations from those of non-occupational etiologies; thus identification of effects is based on obtaining a good occupational history. 4. Five physiological-pathological manifestations of the effects of occupational agents on the heart; this provides a good framework to classify agents. Many are now of historic interest, as controls have reduced hazards, though they still may be encountered. Each will be considered in turn. ANGINA 5. Carbon monoxide is the most commonly encountered occupational and environmental agent with cardiotoxic effects. Photograph shows indoor foundry work, where combustion occurring in limited oxygen supply may lead to CO formation. 6. Methods by which CO has an effect on the aggravation or exacerbation of currentlyexisting cardiovascular disease. Major effect is to increase affinity of hemoglobin for oxygen and thereby cause tissue anoxia. Poster is from 1940’s era public health efforts to raise awareness of CO. 7. Hemoglobin-O2 dissociation curve: Normal (red) and in presence of carbon monoxide (yellow). The curve is equivalent to dissociation seen at a carboxyhemoglobin (COHgb) concentration of about 20%. Note that curve becomes more hyperbolic, less sigmoidal, in the presence of CO: this reflects COHgb’s reduced capacity to release oxygen at low O2 partial pressures. At partial pressure of O2 at which hemoglobin would normally be below 50% saturated, the presence of carboxyhemoglobin raises hemoglobin O2 saturation to around 65% (dotted line). Thus oxygen is not released readily released to anoxic peripheral tissues. 2 8. Note also the reduction in oxygen-carrying capacity at high CO levels, because of tight CO binding to hemoglobin. Thus a 60% COHgb concentration would be equivalent in O2 carrying capacity to an anemia 40% below normal values (eg a hematocrit of 18 to 20%). Actual manifestations would be much worse than that seen in anemia alone, however, because of the accompanying O2 dissociation curve shift. 9. Manifestations of CO poisoning are dependent upon age and current cardiovascular health. Individuals with pre-existing CAD may become symptomatic at very low levels. 10. NIOSH Recommended Exposure Limit (REL) for carbon monoxide is based on keeping blood COHgb levels no higher than 5% at the end of a 10-hour workday. Heavier activity will increase minute ventilation and therefore uptake of CO by lungs; permissible exposures should be adjusted downward accordingly where heavier work takes place. OSHA standard may be protective of most workers, but COHgb levels may exceed 5% at the end of 8-hour shift under this standard. Some workers with current cardiovascular disease may not tolerate these levels, especially if they smoke as well. The Threshold Limit Value (TLV) and Biologic Exposure Index set by the ACGIH are lower, indicating that the OSHA standard and NIOSH limits may not be protective of sensitive workers or groups. The BEI, which indicates a warning level of biologic response to CO, may prove useful for the primary care or emergency physician in documenting CO exposure in a patient. 11. Methylene chloride CH2Cl2 is a solvent that is metabolized rapidly to CO in the bloodstream. Importantly, it can increase COHgb to symptomatic levels in smokers and those working in the presence of CO. 12. More on methylene chloride: It should also be remembered that, as a chlorinated solvent, methylene chloride will have neurotoxic effects on the CNS, particularly at high concentrations or in poor ventilation. 13. OSHA PEL of 25 ppm is designed to keep COHgb concentration below 2-3% at the end of an 8-hour workshift. NIOSH REL is based on methylene chloride’s potential carcinogenicity, and therefore recommends exposures be reduced to the greatest extent possible. Because of its metabolic conversion, clinical effects from CO toxicity arising from methylene chloride may be of longer duration, and monitoring results may continue to indicate persistent high levels of COHgb. 14. Aside from acute effects, carbon monoxide likely has chronic effects on the development of coronary artery disease. The most informative studies in this area come from longterm mortality studies of NYC bridge and tunnel officers who had long-term daily CO exposure at work. 3 15. Standardized mortality ratios from CAD show an increase in cardiovascular mortality in tunnel officers (worksite less well ventilated than the bridges) with ten years or more service. Other studies indicate that this elevated risk declined after cessation of exposure, with much of the risk dissipating within five years. The findings suggest that environmental carbon monoxide exposure plays a role in the pathophysiology of cardiovascular mortality similar to that associated with cigarette smoking. 16. Effects of exposures to aliphatic nitrates (nitroglycerin and ethylene glycol dinitrate) in explosives workers were soon seen after manufacturing rapidly increased in the 19th century. Many developed headaches, tachycardia, syncope (also familiar side effects of the medical use of nitrates); tolerance or tachyphylaxis usually developed over a week or so on the job. Picture shows original DuPont manufacturing houses on Delaware River: note thick walls with buttresses and thin ceilings to channel any explosions upward and back toward woods rather than outward to other areas of plant. 17. Process diagram for nitrate explosives manufacture. Most direct exposures to nitrates occur in manual packing operations. (“Dope” refers to additional combustible materials such as wood pulp, with which the nitrates are combined to form dynamite.) 18. More serious effects were first noted in early 1960’s: Angina or sudden death occurred 48 to 96 hours after workers left factory and nitrate exposures. Clean coronary arteries were noted on autopsies of workers suddenly dying, indicating MI or arrhythmia rather than atherosclerotic coronary disease was responsible. 19. Speculated mechanisms by which effects might occur. Risk persists long after leaving work, indicating that a rebound or similar effect on blood pressure might be responsible for findings. Picture shows WWI-era explosives manufacture with nitroglycerin ribbons emerging from machine for packing. ATHEROGENESIS 20. Carbon disulfide is the occupational agent with the clearest evidence of an effect on atherogenesis and development of ASCVD. Its greatest use is in the artificial fiber and textile industry, and related areas such as the manufacture of cellophane. 4 21. Diagram shows process for viscose rayon manufacture. Cellulose flakes from wood pulp are treated with gaseous carbon disulfide to form xanthate esters: R Cellulose – O – C = S S- Na+ Acid added to the cellulose xanthate produces a thick solution termed “viscose”. This is then allowed to “ripen,” which decreases the solubility of the cellulose; some CS2 is given off in this process. After filtering, the viscose is extruded through a spinneret, and passed through a stronger acid along with zinc ions. This acid treatment causes cellulose molecules to cross-link and CS2 is liberated. Fibers from the spinneret are wound together to produce rayon thread. Production of cellophane is similar. Main occupational exposures occur in cellulose treatment and to spinner operators. 22. Picture shows two steps in viscose process: Cellulose flakes after treatment with lye, and viscose emerging from spinneret. At this point, with acid treatment, CS2 is liberated and rayon is formed by fiber cross-linking. 23. Original paper by Tiller, Shilling and Morris examined long-term effects of CS2 exposure on cardiovascular mortality. Table adapted from paper shows increase in CAD deaths among process operators and other workers in spinning operations. 24. Possible mechanisms by which CS2 may contribute to cardiac disease. Metabolism is complex and leads to intermediates: dithiocarbamates and carbonyl sulfate (COS). These may have a variety of effects on enzyme functions, many not yet well clarified. 25. Japanese workers in rayon industries developed microvascular changes, including retinal aneurysms …. 26. ….and hemorrhages, which indicate a direct effect of CS2, on acceleration of atherogenesis. 27. Exposures have been greatly decreased in the artificial fiber industries since the early 1970’s, to below 10ppm, a level at which increased mortality is no longer seen. Standards noted here: NIOSH recommendations are based on protection against accelerating pre-existing cardiovascular disease. OSHA had petitioned to lower current standard of 10 ppm to 4 ppm, but was rejected by courts. Metabolite of CS2, 2-thiothiazolidine-4-carboxylic acid (TTCA), easily measured in urine. Measurement of TTCA in post-shift urine useful for assessment of workplace exposure and of hygiene controls; ACGIH BEI is 5 mg per gram creatinine. 5 DYSRHYTHMIAS 28. Dysrhythmias and sudden death first noted in solvent abusers and glue sniffers. Ambulatory EKG monitoring showed abnormalities in pathology residents exposed to chlorofluorocarbons such as Freon; these improved with improvements in ventilation. Occasional deaths have been reported from excess physical activity near leaking refrigerants. Autopsy results in cases of sudden death from solvent exposures show no evidence for atherogenesis. CARDIOMYOPATHY 29. Epidemics of cardiomyopathy were seen in the 1960s in Belgium and Quebec, after cobalt was used as an additive to beer to stabilize the foam. 30. Investigation showed risk greatest in heaviest drinkers (those consuming >10 liters/day), many of whom were employed at the breweries and were supplied with beer as a fringe benefit. Mortality from cobalt cardiomyopathy was high. It is unclear however to what extent cobalt represents an occupational toxin; people treated with higher doses of cobalt for anemia do not develop cardiomyopathy, nor do tungsten-carbide tool workers exposed to cobalt, (who may develop hard-metal pneumoconiosis). Cardiomyopathy may have arisen from a combination of heavy alcohol intake, poor nutrition, and cobalt. HYPERTENSION 31. Associations have been drawn between some workplace exposures and the development of hypertension (HTN). Difficulty arises in attribution because of additional predisposing exposures (eg cigarette smoking) and the prevalence of “essential” hypertension without known predisposing causes. 32. Lead has been associated with relative increases in blood pressure and may contribute to the development of hypertension. Mechanisms by which it causes HTN involve renal insufficiency from tubular damage, increased plasma renin activity, and possible direct effects on vascular tone through lead’s effects on calcium transport. Chelation may reduce blood pressure in cases of acute lead intoxication; in chronic cases in which interstitial nephritis is present it is unlikely to be of value. 33. Carbon disulfide increases BP through the same mechanisms noted earlier, with accelerated atherogenesis contributing to renal damage. Of recent interest have been the contributions of shiftwork and noise to the development of HTN. While exposure estimates are difficult to obtain, and studies are confounded by other contributing causes, it appears that there is evidence for a contribution of these exposures to HTN. The contributory pathway is likely increased sympathetic discharge 6 and tone, with release of stress-mediating hormones and mediators. Noise exposure is an important concern for those who are already at risk for HTN (obese, older, family history). CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASE AND THE WORKPLACE 34. A body of work in recent years has demonstrated associations between job strain and mortality form cardiovascular disease. Studies in this area are complicated by difficulties in exposure assessment and control of confounding variables, but indicate that high psychological demands, coupled to low control over work (low autonomy) may be contributory. Urban transit drivers have the most consistent evidence of high risk for ischemic heart disease and hypertension, and there appears to be a risk gradient based on intensity of traffic in the work setting. 35. Marmot’s pioneering work in the UK demonstrated increased cardiovascular mortality among workers in lower socioeconomic positions. Factors contributing to this finding are complex, and may relate to lifestyle factors (diet, exercise, smoking), but control over one’s job (and over others’ work) appears to account for part of the social gradient in mortality seen here. 36. Some figures on the extent of cardiovascular disease in the US. 37. Few objective cardiac tests are able to predict successful return-to-work after MI; many non-medical factors have an effect on perception of cardiac disability and may be more important in predicting who returns. 38. Those working for years in heavy jobs have a reduced incidence of cardiovascular mortality and sudden death, as shown by this study of longshoremen; this appears to be independent of a worker selection effect. Many worker have also, by the time CVD is apparent, channeled themselves into less strenuous work (eg moving from laborer to foreman). 39. Outline for clinical evaluation of patient with cardiovascular disease, assessing work capacity. 40. Objective testing to determine physical capacity can be performed through exercise testing. 41. Isometric work (lifting) may not be as well predicted by exercise testing, and the physiologic mechanisms are different from those that contribute to aerobic capacity. 42. A sample of the exertional requirements of many job tasks. One metabolic equivalent (MET) reflects basal oxygen consumption at rest (3.5 ml O2/Kg/min), METs shown are multiples of the basal rate and can be either directly 7 measured from O2 consumption on exercise or calculated from the work produced on the treadmill. 43. When asked to render an opinion on work fitness, obtain as accurate information on the job demands as can be supplied, including other potential stressors. Evaluation by a cardiologist may be useful, but take care that opinion does not error on the side of overt conservatism or is influenced by patient desires. 44. Guidance for basing a determination of job fitness on results of exercise testing. 8 45. Personality features, coping styles, perception of work demands and degree of control, interpretation of physician recommendations, and other psychologic and social factors influence return-to-work more heavily than do physiologic measures. Despite appropriate evaluation, physicians may be over-cautious in returning individuals with CAD to the workplace. A variety of factors should be considered when evaluating the individual who appears disabled. Can these workers be placed in less strenuous work? Is therapy adequate? Is there co-existing depression (common in those sidelined by an MI) which can be treated? What are the financial incentives that may make disability more attractive than a return to work? 46. Often physicians are asked to use exercise testing in asymptomatic individuals, such as police recruits or firefighters. Risk of a cardiac event is low in these workers: the annual rate of MI in asymptomatic patients who demonstrate ischemia on exercise testing is < 1%. Principles of screening should be borne in mind: the predictive value of a positive test will be low when the prevalence of disease is low. Pre-test screening for cardiac risk factors, such as a positive family history of MI at early age, and performance of test in those aged > 40years may increase the yield of exercise testing in asymptomatic workers. 47. Jobs such as firefighting may have performance requirements (either at hire or regularly during job tenure) based on fitness as measured by treadmill evaluation. The principles outlined above should be borne in mind: younger workers have a low prevalence of disease and positive tests are likely to be false-positives in the absence of other risk factors. Furthermore, office testing may not be predictive of work capacity, especially in the asymptomatic individual with a positive test. Physicians should be careful not to exclude workers on the basis of positive testing without clear demonstration that physical capacity is limited: this would conflict with statutes protecting the disabled such as the ADA. 48. Regulatory and statutory issues that should be considered in assessing return-to-work. Examination guidelines for a commercial driver’s license exclude individuals with evidence for heart disease that may reasonably be expected to be “accompanied by angina, syncope or heart failure.” Aviation medical examinations are considerably more stringent; the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) mandates exclusion of those with “coronary heart disease that has required treatment or, if untreated, that has been symptomatic or clinically significant.” Physicians should also be familiar with the provisions of the ADA and relevant state disability legislation. Under the ADA, the examiner must assess whether the individual with cardiac disease may be accommodated such that essential functions of the job can be 9 performed, and if not, whether the worker would present a direct threat to health or safety on the job. 49. Assessment of whether cardiac disease arose in the course of work or from exposures in the workplace is complicated by the high prevalence of the condition in Western society and the numerous risk factors for cardiac disease present in the population. Unless there is clear evidence of an inciting exposure (eg carbon disulfide above permissible levels for many years), it is difficult to demonstrate causation by workplace factors. In many jurisdictions, however, there is a statutory presumption of causation that is applied to workers primarily in safety-sensitive positions. A diagnosis of coronary heart disease is considered to have arisen out of work if the worker has had the requisite number of years of service. This is designed to reduce contested claims and to ease the pathway toward disability for workers such as firemen and police officers whose heart disease may interfere with safe performance of the job.