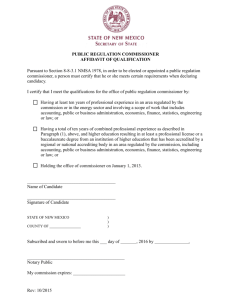

Administrative Appeals Processes

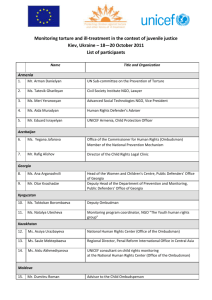

advertisement