Microsoft Word version - Sport and Recreation Victoria

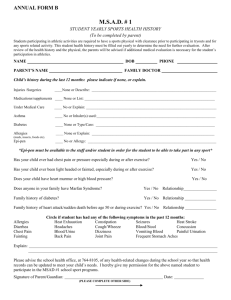

advertisement