Aim 1: compiling a database of PS

advertisement

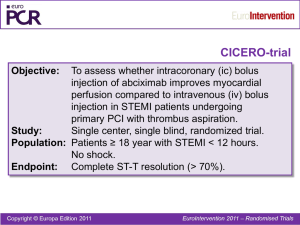

APPENDIX Do observational studies using propensity score methods agree with randomized trials? A systematic comparison of studies on acute coronary syndromes 1 Issa J. Dahabreh MD MS, 2Radley C. Sheldrick PhD, 3,4Jessica K. Paulus ScD, 1Mei Chung PhD MPH, 5Vasileia Varvarigou MD, 6Haseeb Jafri MD, 7,8Jeremy A. Rassen ScD, 1Thomas A. Trikalinos MD PhD, 1,9Georgios D. Kitsios MD PhD 1 Center for Clinical Evidence Synthesis, Institute for Clinical Research and Health Policy Studies, Tufts Medical Center, Boston, MA 2 Division of Developmental-Behavioral Pediatrics, Department of Pediatrics, Floating Hospital for Children, Tufts Medical Center, Boston, MA 3 Tufts Clinical and Translational Science Institute, Tufts University, Medford, MA 4 Department of Epidemiology, Harvard School of Public Health, Boston, MA 5 Department of Environmental and Occupational Medicine & Epidemiology, Harvard School of Public Health, Boston, MA 6 Division of Cardiology, Johns Hopkins Hospital, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD 7 Division of Pharmacoepidemiology & Pharmacoeconomics, Department of Medicine, Brigham & Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA 8 Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA 9 Division of Internal Medicine, Lahey Clinic Medical Center, Burlington, MA 1 Appendix Document: Detailed research methods. Compiling a database of PS-based observational studies This study was based on a pre-specified protocol. We conducted a Medline search to identify studies using propensity score (PS) methods to obtain estimates of treatment efficacy for therapeutic interventions administered to patients with acute coronary syndromes (ACS). ACS was defined as acute myocardial infarction (AMI, including both ST-elevation myocardial infarction, STEMI, and non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction, NSTEMI) or unstable angina (UA). We accepted the specific disease definitions of the primary studies. We used a search strategy developed in Ovid Medline (see Box 1, below). To increase the specificity of the search we limited our searches for studies using PS methods to journals publishing primary clinical research studies and selected the top 8 cardiology journals (Circulation, Journal of the American College of Cardiology, American Journal of Cardiology, Annals of Thoracic Surgery, European Heart Journal, American Heart Journal, Heart, International Journal of Cardiology) and the top 4 general medical journals (New England journal of Medicine, Lancet, Journal of the American Medical Association, British Medical Journal), as defined by 2-year impact factor in 2009 (Institute of Scientific Information, Thomson Reuters, Philadelphia, PA). We screened titles and abstracts to identify studies enrolling patients with an established diagnosis of ACS that used propensity scores to obtain estimates of the efficacy of competing therapeutic interventions. We selected abstract that explicitly reported the inclusion of patients with ACS, i.e. we excluded abstracts that did not specify the patient population included. We randomly sampled 50 of the abstracts excluded because their population was not defined as ACS; of these, none would have been considered eligible 2 for our analyses (they included >20% of non-ACS patients, did not build separate propensity score models or did not report estimates of the treatment effect based on propensity score models built within the ACS subgroup). Because abstract reporting of outcome information is often incomplete, we did not require that mortality was identified as an outcome at the abstract-screening level. Potentially eligible studies were reviewed in full text to determine eligibility by two reviewers (IJD and GK) and discrepancies were resolved by consensus. Eligible studies had to have an observational design, enroll patients with a diagnosis of ACS, and use propensity score methods to obtain estimates for treatment effects of therapeutic interventions on mortality. We considered studies reporting on both short-term (typically within 30 days of ACS diagnosis) and long term (>30 days following ACS diagnosis) mortality. Other outcomes were not considered to limit the potential of outcome misclassification. From each eligible study a single reviewer extracted the following information: first author name, year of publication, population of interest, therapeutic intervention assessed, comparator (no treatment or alternative treatment) assessed, and mortality outcomes assessed (short term and long term). Matching observational studies to RCTs Two reviewers (IJD and GK) independently attempted to match observational studies using PS methods to RCTs using a structured approach (see below). For each observational study the reviewers attempted to identify randomized trials addressing the same intervention and comparator for the same population of patients. 3 a. For interventions and comparators, matching of PS-based studies and RCTs required that studies examined the same pharmaceutical or invasive (nonpharmacological) interventions applied in the same clinical setting (for example, for an observational study reporting the comparison of primary PCI with and without abciximab we required a RCT that examined primary PCI with abciximab versus placebo or no treatment; a RCT that examined the use of multiple IIb/IIIa inhibitors but not exclusively abciximab was not to be considered as an appropriate match). b. For populations, matching was based on the examination of the same subtype of ACS (STEMI vs. NSTEMI vs. mixed) in both study designs (e.g. both observational studies and RCTs examining STEMI patients). For studies enrolling only one subtype of ACS, when no “perfect” match was identified, we used an operational threshold of at least 80% similarity in the type of ACS for each of the compared populations. c. Additional demographic or comorbidity characteristics of the examined populations were considered in the matching process in cases where they represent a selection criterion of the examined population (for example, for observational studies that examined the effects of a treatment in octogenarians, we searched for randomized studies that had included similarly aged patient populations; or for observational studies that included patients with ACS and chronic kidney disease, we searched for RCTs that specifically included ACS patients based on the presence of chronic kidney disease and we will then aimed to match the two study designs based on the severity of kidney disease). 4 d. With regards to the comparability of study outcomes, RCTs will be considered only if they report on the same mortality outcome (operationally classified as short or long term) as the corresponding observational study using PS methods. To identify potential “matches” for each PS based study we used the following structured approach: a. We conducted searches in the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews to identify reviews published or updated after 2008 (to ensure the results were current) investigating the same population, treatments and outcomes as the observational studies using PS methods. b. When such a review was not available we performed Medline searches using terms relevant to systematic reviews and the intervention of interest. We also examined the recently updated, evidence-based guidelines of the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiologists (AHA/ACC) to identify eligible trials (that were considered relevant to the same population and intervention reported in the observational studies) and we also evaluated the relevant chapters of a recent compendium of therapeutics (Washington Manual of Medical Therapeutics) for citations of eligible RCTs. c. We then performed targeted Medline searches (with key words relevant to the specific intervention, population and randomized trial design) for eligible primary RCTs. d. When no RCT investigating the same comparison (population, intervention and outcome) as the observational study, we considered using treatment effect 5 estimates for specific subgroups of interest from individual patient data metaanalyses of RCTs (when such meta-analyses were identified by the literature searches described above). e. As a final matching step, we considered subgroups of interest from single RCTs, provided that these RCTs are large enough to provide precise treatment estimates (at least 1000 patients). f. As one mechanism to verify our matches (as well as a potential source of matching RCTs when none of the sources described above led to the identification of an adequately similar RCT), we also consulted the reference lists of the observational studies study to identify any RCTs that the observational study’s authors had considered sufficiently similar to their investigation (in terms of populations enrolled and interventions assessed). We searched these sources successively: we proceeded to a step only if at least one matching RCT was not identified at the previous step (a to f). When a relevant metaanalysis was identified (steps a and b) all included trials were retrieved and examined in full text for potential matches. When individual trials (or subgroups of trial) were considered (steps c and e) all trials identified through our searches were considered. In cases when an observational study using propensity score methods could be matched to multiple meta-analyses, we considered the largest meta-analysis (i.e. the one including more trials) as the primary source of matching RCTs (but we also verified that all RCTs from previous reviews had been included in the latest one to account for potential 6 differences in selection criteria or search strategies among systematic reviews on the same topic). We realize that there is inherent subjectivity in identifying observational studies and RCTs that were sufficiently similar with regards to their populations and interventions. This is an inherent imitation to all empirical investigations similar to ours. To limit the potential for bias, two investigators (both physicians with training in epidemiological and systematic review methods, IJD and GK) independently attempted to match observational studies with RCTs. Given the complexity of the process, agreement was not assessed formally and all decisions were reached by consensus. Another reviewer (HJ) verified all the matches of observational studies to RCTs after a provisional matched set had been generated in order to finalize the dataset (used for data extraction and analyses). Assessing the validity of PS-based analyses To assess the quality of the observational studies using propensity score methods that were successfully matched to at least one RCT, we extracted information on previously established criteria relevant to the study design and statistical analyses of these studies (Box 2). This extraction was performed by a single reviewer (CRS, JKP, MC, VV) and verified by another reviewer (IJD or GK). 7 Box 1: Search strategy for identifying observational studies using propensity score methods. Searches Results 1 propensity.mp. 17264 2 "new england journal of medicine".jn. 61713 3 lancet.jn. 117312 4 "journal of the american medical association".jn. 7831 5 british medical journal.jn. 41373 6 "annals of internal medicine".jn. 25522 7 circulation.jn. 34997 8 "journal of the american college of cardiology".jn. 16940 9 "american journal of cardiology".jn. 30523 10 "annals of thoracic surgery".jn. 25135 11 european heart journal.jn. 11110 12 american heart journal.jn. 20548 13 heart.jn. 6655 14 "international journal of cardiology".jn. 10124 15 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 or 7 or 8 or 9 or 10 or 11 or 12 or 13 or 14 409783 16 1 and 15 515 17 myocardial infarction.mp. or exp Myocardial Infarction/ 160416 18 Coronary artery disease.mp. or exp Coronary Artery Disease/ 61912 19 Coronary disease.mp. or exp Coronary Disease/ 162457 20 heart disease.mp. or exp Heart Diseases/ 784888 21 17 or 18 or 19 or 20 805001 22 18 and 21 599 8 Box 2: Information extracted from observational studies using propensity score methods. Author, year, journal of publication Population o STEMI o NSTEMI o UA o If mixed ACS: % NSTEMI/UA Intervention, Comparator Outcome: (description, binary vs. time-to-event) o Short term mortality (≤30d) o Long term mortality (>30d) Design: o Prospective o Recruitment from RCT population o Dataset source (administrative vs. clinical) o Sample size (overall / intervention / comparator groups) Multivariate outcome model without PS o Logistic regression o Cox-model o Other (detailed description) o N of variables in final model o N of outcomes per variable Propensity score estimation o Logistic regression o Other generalized model o N of variables in model o N of outcomes per variable o Reporting of included variables o Selection of included variables Reported vs. NR If reported Literature review for predictors of exposure Expert knowledge of predictors of exposure+ and outcome Predictors of exposure from prior studies Stepwise selection Examination of imbalances between treated and untreated groups o AUC of PS Use of Propensity score: o MATCHING: Y/N Process for formation of matched pairs reported Ratio of matching: (e.g. 1:2, 1:1) Assessment of balance between matched pairs N of matched pairs N of unmatched treated N of unmatched untreated Did the method used to estimate the treatment effect take into account the paired nature of data? o STRATIFICATION N of strata Assessment of balance following stratification Method for estimation of overall Tx effect o REGRESSION ADJUSTMENT WITH PS o Specification of PS variable functional form in model o IPW WITH PS Detailed extraction of results based on the underlying analysis o PS-matched analysis, effect size reported or calculated, p-value o PS-stratified analysis, effect size reported or calculated, p-value o PS-adjusted analysis, effect size reported or calculated, p-value o PS-weighted analysis, effect size reported or calculated, p-value o MV model without PS, effect size reported or calculated, p-value 9 Appendix Figure 1: A. Relative risks from randomized controlled trials (white circles) and observational studies using propensity score methods (red squares) reporting on short-term mortality, stratified by topic. B. Relative risks from randomized controlled trials (white circles) and observational studies using propensity score methods (red squares) reporting on short-term mortality, stratified by topic. Extending lines depict 95% confidence intervals for the estimates. Arrows indicate lower or upper bounds of confidence intervals that were outside the plotted range of values. 10 Appendix Figure 2: Relative risks from observational studies using both propensity score methods (red squares) and simple regression adjustments (black squares). Estimates from analyses using propensity score methods are depicted as Extending lines depict 95% confidence intervals for the estimates. 11 Appendix Table 1: Detailed characteristics of observational studies using propensity score methods and matched randomized controlled trials investigating the same interventions and patient populations. Treatment Publication Population information Short-term mortality - Pharmacological interventions Abciximab timing in pPCI Dudek, 2008, Am STEMI planned to be Heart J1 treated with primary PCI IIb/IIIa inhibitors (NSTE-ACS) Statins timing (AMI) Intervention Comparator Outcome (Mortality) Design early abciximab administration (before admission to cathlab for primary PCI) late abciximab administration (periprocedural) 30 d PS Maioli (RELAxAMI), 2007, JACC2 STEMI planned to be treated with primary PCI early abciximab administration (before admission to cathlab for primary PCI) late abciximab administration (periprocedural, after angiography) 30 d RCT Zorman, 2002, Am J Cardiol3 STEMI planned to be treated with primary PCI early abciximab administration (before admission to cathlab for primary PCI) late abciximab administration (periprocedural, after angiography) in-hospital RCT Gabriel (ERAMI), 2006, Catheter Cardiovasc Interv4 STEMI planned to be treated with primary PCI early abciximab administration (before admission to cathlab for primary PCI) late abciximab administration (periprocedural, after angiography) 30 d RCT Peterson, 2003, JACC5 PURSUIT, 1998, NEJM6 GUSTO IV-ACS, 2001, Lancet7 Fonarow, 2005, Am J Cardiol8 NSTEMI IIb/IIIa inhibitor within 24h of presentation eptifibatide within 24h of presentation abciximab within 24h of presenting with symptoms statin initiation within first 24h of admission no IIb/IIIa within 24h of presentation placebo in-hospital PS 7d RCT placebo 7d RCT no statin within first 24h of admission in-hospital PS NSTE-ACS NSTE-ACS AMI (73% NSTEMI) 12 Treatment Publication Population information Sakamoto, 2006, AMI (11% NSTEMI) Am J Cardiol9 Macin, 2005, Am ACS (NR% NSTE-ACS) Heart J10 Short-term mortality – non-pharmacological interventions pPCI (shock) Babaev, 2005, STEMI with shock JAMA11 pPCI (elderly) Invasive strategy timing (NSTE-ACS) Intervention Comparator Design no statin Outcome (Mortality) 7d statin initiation within 96h of symptom onset statin initiation within 48h of symptom onset no statin 30 d RCT primary PCI medical management in-hospital PS RCT Urban, 1999, Eur Heart J12 AMI with shock (20% NSTEMI) early angiography followed by revascularization when indicated (84% received PCI) initial medical management 30 d RCT Mehta, 2004, Am Heart J13 de Boer, 2002, JACC14 Bueno (TRIANA), 2011, Eur Heart J15 SENIOR PAMI, 2005, unpublished Shavelle, 2002, Am Heart J16 Montalescot (ABOARD), 2009, JAMA17 Neumann (ISARCOOL), 2003, JAMA18 van'tHof (ELISA), 2003, Eur Heart J19 STEMI, >70 years primary PCI thrombolysis in-hospital PS STEMI, >75 years primary PCI thrombolysis in-hospital RCT STEMI, >75 years primary PCI thrombolysis 30 d RCT STEMI, >70 years primary PCI thrombolysis 30 d RCT NSTEMI with ST-segment depression NSTE-ACS early angiography (<6h) early conservative therapy in-hospital PS immediate angiography delayed angiography for next working day 30 d RCT NSTE-ACS early angiography (<6h) delayed angiography (>3 d) 30 d RCT NSTE-ACS early angiography (<12h) delayed angiography (>24h) 30 d RCT 13 Treatment Invasive strategy (NSTE-ACS) Publication information Bhatt, 2004, JAMA20 Population Intervention Comparator NSTE-ACS angiography within 48h of presentation early conservative strategy (no angiography within 48 h of presentation) TIMI IIIB, 1994, Circulation21 NSTE-ACS FRISC II, 1999, Lancet22 NSTE-ACS Spacek (VINO), 2002, Eur Heart J23 NSTEMI Cannon (TACTICSTIMI 18), 2001, NEJM24 NSTE-ACS Fox (RITA 3), 2002, Lancet25 NSTE-ACS angiography within 48h of randomization (followed by revascularization, when indicated) angiography within 1 wk of randomization (followed by revascularization, when indicated) angiography within 24h of symptom onset (followed by revascularization, when indicated) angiography within 48h of randomization (followed by revascularization, when indicated) angiography within 3 d of randomization Boden (VANQWISH), 1998, NEJM26 NSTEMI angiography within 3 d of symptom onset (followed by revascularization, when indicated) AMI (54% NSTEMI) Long-term mortality - Pharmacological interventions ACEi (AMI) Milonas, 2010, Am J Cardiol27 Ambrosioni (SMILE), 1995, NEJM28 Kleber (ECCE), Outcome (Mortality) in-hospital Design early conservative strategy (angiography performed when indicated by symptoms or functional test results) early conservative strategy (angiography performed when indicated by symptoms or functional test results) early conservative strategy (angiography performed when indicated by symptoms or functional test results) early conservative strategy (angiography performed when indicated by symptoms or functional test results) early conservative strategy (angiography performed when indicated by symptoms or functional test results) early conservative strategy (angiography performed when indicated by symptoms or functional test results) in-hospital RCT in-hospital RCT in-hospital RCT in-hospital RCT in-hospital RCT in-hospital RCT no ACE inhibitor treatment at discharge placebo 12 mo PS anterior AMI (34% NSTEMI) ACE inhibitor treatment at discharge zofenopril administered within 24h of symptoms and for 6 wk 12 mo RCT AMI (NR% NSTEMI) captopril administered within 72h placebo 3 mo RCT PS 14 Treatment IIb/IIIa inhibitor type in pPCI Statins (ACS) Statins (NSTE-ACS) Publication information 1997, Am J Cardiol29 Foy (PRACTICAL), 1994, Am J Cardiol30 Akerblom, 2010, JACC31 Zeymer (EVA-AMI), 2010, JACC32 Stenestrand, 2001, JAMA33 Newby, 2002, JAMA34 Smith, 2005, Am Heat J35 Population Intervention Comparator Outcome (Mortality) Design of symptoms and for 4 wk AMI (28% NSTEMI) captopril or enalapril within 24h of symptoms and for 12 mo placebo 3 mo RCT STEMI treated with primary PCI STEMI, planned primary PCI (95% received primary PCI) AMI (NR% NSTEMI) eptifibatide abciximab 12 mo PS eptifibatide abciximab 6 mo RCT statin treatment at discharge no statin treatment at discharge 12 mo PS ACS (NR% NSTE-ACS) statin initiation within 7 d of ACS no statin with 7 d of ACS 12 mo PS ACS (75% NSTE-ACS) lipid-lowering therapy (94% statin) started during index hospitalization statin within 96 h of symptom onset fluvastatin 80 mg within 1 h of admission fluvastatin 40 mg at least 1 d prior to discharge and no later than 14 d after AMI pravastatin 10 mg in the week after AMI onset no lipid lowering therapy during index hospitalization 10 mo PS no statin 24 mo RCT placebo 12 mo RCT placebo 12 mo RCT no pravastatin 9 mo RCT pravastatin 40 mg within 48 h of admission Combination treatment at discharge consisting of aspirin, clopidogrel and statin lipid lowering agent treatment on discharge (surrogate of statin placebo 3 mo RCT Combination treatment at discharge consisting of aspirin and clopidogrel (no statin) no lipid lowering agent on discharge 6 mo PS 6 mo PS Sakamoto, 2006, Am J Cardiol9 Ostadal (FACS), 2010, Trials36 Liem (FLORIDA), 2002, Eur Heart J37 AMI (11% NSTEMI) Sato (OACISLIPID), 2008, Circ J38 Den Hartog, 2001, Int J Clin Pract39 Lim, 2005, Eur Heart J40 AMI (29% NSTEMI) Aronow, 2001, Lancet41 ACS (81% NSTE-ACS) ACS (35% NSTE-ACS) AMI (NR% NSTEMI) ACS (NR% NSTE-ACS) NSTE-ACS 15 Treatment Publication information Population Colivicchi, 2002, Am J Cardiol42 NSTE-ACS Schwartz NSTE-ACS (MIRACL), 2001, JAMA43 Long-term mortality – non-pharmacological interventions Invasive strategy (NSTE-ACS, Szummer NSTEMI with CKD≥stage CKD) (SWEDEHEART), 3 2009, Circulation44 TIMI IIIB, 1994, NSTE-ACS with Circulation21 CKD≥stage 3 Intervention treatment) atorvastatin 80 mg on top of conventional medical treatment (including antilipidemic therapy based on NCEP guidelines) at discharge atorvastatin 80 mg within 24-96 h of admission Comparator Outcome (Mortality) Design conventional medical treatment (antilipidemic therapy based on NCEP guidelines) 12 mo (stopped early, all patients followed up >=60 d postrandomization) 4 mo RCT placebo RCT revascularization within 14 d of admission no revascularization within 14 d of admission 12 mo PS angiography within 48h of randomization (followed by revascularization, when indicated) [89% received revascularization during index hospitalization] early conservative strategy (angiography performed when indicated by symptoms or functional test results) [65% received revascularization during index hospitalization] 12 mo RCT FRISC II, 1999, Lancet22 NSTE-ACS with CKD≥stage 3 angiography within 1 wk of randomization (followed by revascularization, when indicated) [≈100% received revascularization during index hospitalization] early conservative strategy (angiography performed when indicated by symptoms or functional test results) [29% received revascularization during index hospitalization] 12 mo RCT Spacek (VINO), 2002, Eur Heart J23 NSTEMI with CKD≥stage 3 angiography within 24h of symptom onset (followed by revascularization, when indicated) [85% received revascularization during index hospitalization] early conservative strategy (angiography performed when indicated by symptoms or functional test results) [71% received revascularization during index hospitalization] 12 mo RCT 16 Treatment Invasive strategy timing (NSTE-ACS, elderly) DES in pPCI Publication information Cannon (TACTICSTIMI 18), 2001, Circulation24 Population Intervention Comparator Outcome (Mortality) 12 mo Design NSTE-ACS with CKD≥stage 3 angiography within 48h of randomization (followed by revascularization, when indicated) [54% received revascularization during index hospitalization] early conservative strategy (angiography performed when indicated by symptoms or functional test results) [31% received revascularization during index hospitalization] de Winter (ICTUS), 2005, NEJM45 NSTEMI with CKD≥stage 3 angiography within 48h of randomization (followed by revascularization, when indicated) [79% received revascularization during index hospitalization] early conservative strategy (angiography performed when indicated by symptoms or functional test results) [41% received revascularization during index hospitalization] 12 mo RCT Bauer, 2007, Eur Heart J46 NSTEMI, ≥75 years angiography (followed by revascularization, when indicated) within index hospitalization angiography within 48h of randomization (followed by revascularization, when indicated) no angiography within index hospitalization 12 mo PS Bach (TACTICSTIMI 18), 2004, Ann Intern Med47 NSTE-ACS, >75 years early conservative strategy (angiography performed when indicated by symptoms or functional test results) 6 mo RCT Gurvitch, 2010, Int J Cardiol48 Steg, 2009, Eur Heart J49 Diaz de la Llera, 2007, Am Heart J50 Kelbaek (DEDICATION), 2008, Circulation51 Stone (HORIZONSAMI), 2009, NEJM52 van der Hoeven STEMI treated with primary PCI STEMI treated with primary PCI STEMI, candidates for primary PCI STEMI,candidates for primary PCI primary PCI with DES primary PCI with BMS 12 mo PS primary PCI with DES primary PCI with BMS 12 mo PS primary PCI with sirolimus-eluting stents primary PCI with DES primary PCI with BMS 12 mo RCT primary PCI with BMS 8 mo RCT STEMI, candidates for primary PCI STEMI, candidates for primary PCI with paclitaxeleluting stents primary PCI with sirolimus-eluting primary PCI with BMS 12 mo RCT primary PCI with BMS 12 mo RCT RCT 17 Treatment Exercise rehabilitation (AMI) Publication information (MISSION!), 2008, JACC53 Valgimigli (MULTISTRATEGY ), 2008, JAMA54 Laarman (PASSION), 2006, NEJM55 Chechi (SELECTION), 2007, J Interv Cardiol56 Meninchelli (SESAMI), 2007, JACC57 Spaulding (TYPHOON), 2006, NEJM58 Witt, 2004, JACC59 Population Intervention Comparator Outcome (Mortality) Design primary PCI stents STEMI, candidates for primary PCI primary PCI with sirolimus-eluting stents primary PCI with BMS 8 mo RCT STEMI, candidates for primary PCI primary PCI with paclitaxeleluting stents primary PCI with BMS 12 mo RCT STEMI, candidates for primary PCI primary PCI with paclitaxeleluting stents primary PCI with BMS 7 mo RCT STEMI, candidates for primary PCI primary PCI with sirolimus-eluting stents primary PCI with BMS 12 mo RCT STEMI, candidates for primary PCI primary PCI with sirolimus-eluting stents primary PCI with BMS 12 mo RCT AMI (NR% NSTEMI) cardiac rehabilitation program with exercise component Cardiac rehabilitation invovling group education or counseling sessions about risk factor management plus exercise program Cardiac rehabilitation involving multidisciplinary team with exercise rehabilitation and social and psychological support no cardiac rehabilitation 36 mo PS Sivarajan, 1982, Circulation60 AMI (NR% NSTEMI) control group 6 mo RCT Vermeulen, 1983, Am Heart J61 AMI (NR% NSTEMI) control group 12 mo RCT WHO trial, 1983, WHO62 AMI (NR% NSTEMI) Cardiac rehabilitation involving multidisciplinary team for patient health education and supervised exercise program control group 36 mo RCT 18 Treatment Complete PCI revascularization (STEMI) Publication information Fridlund, 1991, Scan J Caring Sci63 Population Intervention Comparator Outcome (Mortality) 12 mo Design AMI (NR% NSTEMI) control group (routine cardiac followups) Oldridge, 1991, Am J Cardiol64 AMI patients (NR% NSTEMI) Nurse-led cardiac rehabilitation program addressing lifestyle, stress, and social support plus exercise component cardiac rehabilitation involving behavioral counseling and supervised exercise training control group (usual care) 12 mo RCT PRECOR, 1991, Eur Heart J65 AMI patients (NR% NSTEMI) cardiac rehabilitation involving supervised exercise program, relaxation training, risk factor management and education cardiac rehabilitation involving nurse-managed patient education and counseling, exercise program, frequent telephone contact, and algorithm-based lipid therapy Cardiac rehabilitation involving supervised exercise program, group education sessions on risk factor management Cardiac rehabilitation involving supervised exercise training and education or counseling about risk factor management, with optional monthly support groups control group (usual care) 24 mo RCT deBusk, 1994, Ann Intern Med66 AMI patients (NR% NSTEMI) control group (usual care) 12 mo RCT Bell, 1998, unpublished AMI patients (NR% NSTEMI) control group (usual care) 12 mo RCT Marchionni, 2003, Circulation67 AMI patients (NR% NSTEMI) no cardiac rehabilitation 12 mo RCT Kalarus, 2007, Am Heart J68 STEMI patients with multivessel CAD complete PCI revascularization incomplete PCI revascularization 29 mo PS RCT 19 Treatment Invasive strategy (NSTE-ACS) Publication information Di Mario, 2004, Int J Cardiovasc Intervent69 Politi, 2009, Heart70 Ottervanger, 2004, Eur Heart J71 TIMI IIIB, 1994, Circulation21 Population Intervention Comparator STEMI patients with multivessel CAD complete PCI revascularization culprit only PCI revascularization STEMI patients with multivessel CAD NSTE-ACS patients (30 d survivors) NSTE-ACS patients complete PCI revascularization culprit only PCI revascularization no revascularization within 30d of presentation early conservative strategy (angiography performed when indicated by symptoms or functional test results) [40% received revascularization during index hospitalization] early conservative strategy (angiography performed when indicated by symptoms or functional test results) [9% received revascularization during index hospitalization] early conservative strategy (angiography performed when indicated by symptoms or functional test results) [39% received revascularization during index hospitalization] early conservative strategy (angiography performed when indicated by symptoms or functional test results) [36% received revascularization during index hospitalization] early conservative strategy (angiography performed when indicated by symptoms or FRISC II, 1999, Lancet22 NSTE-ACS patients Spacek (VINO), 2002, Eur Heart J23 NSTEMI patients Cannon (TACTICSTIMI 18), 2001, Circulation24 NSTE-ACS patients Fox (RITA 3), 2002, Lancet25 NSTE-ACS patients revascularization within 30d of presentation angiography within 48h of randomization (followed by revascularization, when indicated) [60% received revascularization during index hospitalization] angiography within 1 wk of randomization (followed by revascularization, when indicated) [71% received revascularization during index hospitalization] angiography within 24h of symptom onset (followed by revascularization, when indicated) [78% received revascularization during index hospitalization] angiography within 48h of randomization (followed by revascularization, when indicated) [60% received revascularization during index hospitalization] angiography within 3 d of randomization (followed by revascularization, when Outcome (Mortality) 12 mo Design 12 mo RCT 12 mo PS 12 mo RCT 12 mo RCT 6 mo RCT 6 mo RCT 24 mo RCT RCT 20 Treatment Publication information Population Intervention Comparator Outcome (Mortality) Design indicated) [44% received functional test results) [10% revascularization during index received revascularization hospitalization] during index hospitalization] Boden NSTEMI patients angiography within 3 d of early conservative strategy 23 mo RCT (VANQWISH), symptom onset (followed by (angiography performed when 1998, NEJM26 revascularization, when indicated by symptoms or indicated) [44% received functional test results) [33% revascularization during index received revascularization hospitalization] during index hospitalization] ACS = acute coronary syndrome; CAD = coronary artery disease; d = days; mo = months, NR = not reported; NSTE = non-ST-elevation; NSTEMI, non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction; PCI = percutaneous coronary intervention; RCT = randomized controlled trial; STEMI = ST-elevation myocardial infarction. 21 Appendix Table 2: Study design and statistical methods reporting characteristics of the 21 observational studies that used propensity-score methods. Characteristics Study design Prospective Patient sampling from RCT population Administrative dataset Statistical analyses unrelated to PS Reporting of analyses based on multivariate regression methods without PS Statistical analyses related to developing the PS PS estimation method Reporting of variables used for PS estimation Reporting of variable selection method Reporting of AUC for the PS model Median AUC (25th-75th percentile) Statistical analyses related to developing the PS Matching on PS (5 studies, all used 1:1 matching) Process of matching reported Assessment of covariate balance between matched pair groups N of matched pairs (median) N of treated patients left unmatched (median) N of treated patients left unmatched (median) Analysis method accounting for matching N (%) Yes No Yes No Yes No 19 (90%) 2 (10%) 4 (19%) 17 (81%) 1 (5%) 20 (95%) Yes No 11 (55%) 10 (45%) Logistic regression Other model Yes No Yes (stepwise selection in all cases) No Yes No 20 (95%) No Yes No Yes Yes No 1 (5%) 18 (95%) 3 (5%) 10 (48%) 11 (52%) 11 (52%) 10 (48%) 0.78 (0.69-0.81) 2 (40%) 3 (60%) 2 (40%) 3 (60%) 9819 1113 23785 2 (40%) 3 (60%) Stratification based on PS (4 studies, all using 5 strata) Assessment of covariate balance following stratification Yes 2 (50%) No 2 (50%) Method for estimating treatment effect across strata IV 2 (50%) Other/NR 2 (50%) Regression analysis with PS included as a covariate in the model (18 studies) Specification of the functional form for the PS variable in the model No 14 (78%) Yes 4 (22%) No study used the propensity score to derive inverse probability of treatment weights. For studies that used the PS in multiple analytic approaches (for example, regression and stratification) we extracted information for all performed analyses, even if treatment effect estimates were not reported from some. Of the studies using both regression- and non-regression-based analyses utilizing the PS, only 3 reported treatment effect estimates from both approaches. IV = inverse variance; NR = not reported; PS = propensity score 22 References to included studies 1. Dudek D, Siudak Z, Janzon M, et al. European registry on patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction transferred for mechanical reperfusion with a special focus on early administration of abciximab -- EUROTRANSFER Registry. Am Heart J 2008;156:114754. 2. Maioli M, Bellandi F, Leoncini M, Toso A, Dabizzi RP. Randomized early versus late abciximab in acute myocardial infarction treated with primary coronary intervention (RELAx-AMI Trial). J Am Coll Cardiol 2007;49:1517-24. 3. Zorman S, Zorman D, Noc M. Effects of abciximab pretreatment in patients with acute myocardial infarction undergoing primary angioplasty. Am J Cardiol 2002;90:5336. 4. Gabriel HM, Oliveira JA, da Silva PC, da Costa JM, da Cunha JA. Early administration of abciximab bolus in the emergency department improves angiographic outcome after primary PCI as assessed by TIMI frame count: results of the early ReoPro administration in myocardial infarction (ERAMI) trial. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 2006;68:218-24. 5. Peterson ED, Pollack CV, Jr., Roe MT, et al. Early use of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors in non-ST-elevation acute myocardial infarction: observations from the National Registry of Myocardial Infarction 4. J Am Coll Cardiol 2003;42:45-53. 6. Inhibition of platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa with eptifibatide in patients with acute coronary syndromes. The PURSUIT Trial Investigators. Platelet Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa in Unstable Angina: Receptor Suppression Using Integrilin Therapy. N Engl J Med 1998;339:436-43. 7. Simoons ML. Effect of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa receptor blocker abciximab on outcome in patients with acute coronary syndromes without early coronary revascularisation: the GUSTO IV-ACS randomised trial. Lancet 2001;357:1915-24. 8. Fonarow GC, Wright RS, Spencer FA, et al. Effect of statin use within the first 24 hours of admission for acute myocardial infarction on early morbidity and mortality. Am J Cardiol 2005;96:611-6. 9. Sakamoto T, Kojima S, Ogawa H, et al. Effects of early statin treatment on symptomatic heart failure and ischemic events after acute myocardial infarction in Japanese. Am J Cardiol 2006;97:1165-71. 10. Macin SM, Perna ER, Farias EF, et al. Atorvastatin has an important acute antiinflammatory effect in patients with acute coronary syndrome: results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Am Heart J 2005;149:451-7. 11. Babaev A, Frederick PD, Pasta DJ, Every N, Sichrovsky T, Hochman JS. Trends in management and outcomes of patients with acute myocardial infarction complicated by cardiogenic shock. JAMA 2005;294:448-54. 12. Urban P, Stauffer JC, Bleed D, et al. A randomized evaluation of early revascularization to treat shock complicating acute myocardial infarction. The (Swiss) Multicenter Trial of Angioplasty for Shock-(S)MASH. Eur Heart J 1999;20:1030-8. 13. Mehta RH, Sadiq I, Goldberg RJ, et al. Effectiveness of primary percutaneous coronary intervention compared with that of thrombolytic therapy in elderly patients with acute myocardial infarction. Am Heart J 2004;147:253-9. 23 14. de Boer MJ, Ottervanger JP, van 't Hof AW, Hoorntje JC, Suryapranata H, Zijlstra F. Reperfusion therapy in elderly patients with acute myocardial infarction: a randomized comparison of primary angioplasty and thrombolytic therapy. J Am Coll Cardiol 2002;39:1723-8. 15. Bueno H, Betriu A, Heras M, et al. Primary angioplasty vs. fibrinolysis in very old patients with acute myocardial infarction: TRIANA (TRatamiento del Infarto Agudo de miocardio eN Ancianos) randomized trial and pooled analysis with previous studies. Eur Heart J 2011;32:51-60. 16. Shavelle DM, Parsons L, Sada MJ, French WJ, Every NR. Is there a benefit to early angiography in patients with ST-segment depression myocardial infarction? An observational study. Am Heart J 2002;143:488-96. 17. Montalescot G, Cayla G, Collet JP, et al. Immediate vs delayed intervention for acute coronary syndromes: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2009;302:947-54. 18. Neumann FJ, Kastrati A, Pogatsa-Murray G, et al. Evaluation of prolonged antithrombotic pretreatment ("cooling-off" strategy) before intervention in patients with unstable coronary syndromes: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2003;290:1593-9. 19. van 't Hof AW, de Vries ST, Dambrink JH, et al. A comparison of two invasive strategies in patients with non-ST elevation acute coronary syndromes: results of the Early or Late Intervention in unStable Angina (ELISA) pilot study. 2b/3a upstream therapy and acute coronary syndromes. Eur Heart J 2003;24:1401-5. 20. Bhatt DL, Roe MT, Peterson ED, et al. Utilization of early invasive management strategies for high-risk patients with non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes: results from the CRUSADE Quality Improvement Initiative. JAMA 2004;292:2096-104. 21. Effects of tissue plasminogen activator and a comparison of early invasive and conservative strategies in unstable angina and non-Q-wave myocardial infarction. Results of the TIMI IIIB Trial. Thrombolysis in Myocardial Ischemia. Circulation 1994;89:154556. 22. Invasive compared with non-invasive treatment in unstable coronary-artery disease: FRISC II prospective randomised multicentre study. FRagmin and Fast Revascularisation during InStability in Coronary artery disease Investigators. Lancet 1999;354:708-15. 23. Spacek R, Widimsky P, Straka Z, et al. Value of first day angiography/angioplasty in evolving Non-ST segment elevation myocardial infarction: an open multicenter randomized trial. The VINO Study. Eur Heart J 2002;23:230-8. 24. Cannon CP, Weintraub WS, Demopoulos LA, et al. Comparison of early invasive and conservative strategies in patients with unstable coronary syndromes treated with the glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor tirofiban. N Engl J Med 2001;344:1879-87. 25. Fox KA, Poole-Wilson PA, Henderson RA, et al. Interventional versus conservative treatment for patients with unstable angina or non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction: the British Heart Foundation RITA 3 randomised trial. Randomized Intervention Trial of unstable Angina. Lancet 2002;360:743-51. 26. Boden WE, O'Rourke RA, Crawford MH, et al. Outcomes in patients with acute nonQ-wave myocardial infarction randomly assigned to an invasive as compared with a conservative management strategy. Veterans Affairs Non-Q-Wave Infarction Strategies in Hospital (VANQWISH) Trial Investigators. N Engl J Med 1998;338:1785-92. 24 27. Milonas C, Jernberg T, Lindback J, Agewall S, Wallentin L, Stenestrand U. Effect of Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition on one-year mortality and frequency of repeat acute myocardial infarction in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol 2010;105:1229-34. 28. Ambrosioni E, Borghi C, Magnani B. The effect of the angiotensin-convertingenzyme inhibitor zofenopril on mortality and morbidity after anterior myocardial infarction. The Survival of Myocardial Infarction Long-Term Evaluation (SMILE) Study Investigators. N Engl J Med 1995;332:80-5. 29. Kleber FX, Sabin GV, Winter UJ, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors in preventing remodeling and development of heart failure after acute myocardial infarction: results of the German multicenter study of the effects of captopril on cardiopulmonary exercise parameters (ECCE). Am J Cardiol 1997;80:162A-7A. 30. Foy SG, Crozier IG, Turner JG, et al. Comparison of enalapril versus captopril on left ventricular function and survival three months after acute myocardial infarction (the "PRACTICAL" study). Am J Cardiol 1994;73:1180-6. 31. Akerblom A, James SK, Koutouzis M, et al. Eptifibatide is noninferior to abciximab in primary percutaneous coronary intervention: results from the SCAAR (Swedish Coronary Angiography and Angioplasty Registry). J Am Coll Cardiol 2010;56:470-5. 32. Zeymer U, Margenet A, Haude M, et al. Randomized comparison of eptifibatide versus abciximab in primary percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: results of the EVA-AMI Trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 2010;56:463-9. 33. Stenestrand U, Wallentin L. Early statin treatment following acute myocardial infarction and 1-year survival. JAMA 2001;285:430-6. 34. Newby LK, Kristinsson A, Bhapkar MV, et al. Early statin initiation and outcomes in patients with acute coronary syndromes. JAMA 2002;287:3087-95. 35. Smith CS, Cannon CP, McCabe CH, Murphy SA, Bentley J, Braunwald E. Early initiation of lipid-lowering therapy for acute coronary syndromes improves compliance with guideline recommendations: observations from the Orbofiban in Patients with Unstable Coronary Syndromes (OPUS-TIMI 16) trial. Am Heart J 2005;149:444-50. 36. Ostadal P, Alan D, Vejvoda J, et al. Fluvastatin in the first-line therapy of acute coronary syndrome: results of the multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebocontrolled trial (the FACS-trial). Trials 2010;11:61. 37. Liem AH, van Boven AJ, Veeger NJ, et al. Effect of fluvastatin on ischaemia following acute myocardial infarction: a randomized trial. Eur Heart J 2002;23:1931-7. 38. Sato H, Kinjo K, Ito H, et al. Effect of early use of low-dose pravastatin on major adverse cardiac events in patients with acute myocardial infarction: the OACIS-LIPID Study. Circ J 2008;72:17-22. 39. Den Hartog FR, Van Kalmthout PM, Van Loenhout TT, Schaafsma HJ, Rila H, Verheugt FW. Pravastatin in acute ischaemic syndromes: results of a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Int J Clin Pract 2001;55:300-4. 40. Lim MJ, Spencer FA, Gore JM, et al. Impact of combined pharmacologic treatment with clopidogrel and a statin on outcomes of patients with non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes: perspectives from a large multinational registry. Eur Heart J 2005;26:1063-9. 25 41. Aronow HD, Topol EJ, Roe MT, et al. Effect of lipid-lowering therapy on early mortality after acute coronary syndromes: an observational study. Lancet 2001;357:10638. 42. Colivicchi F, Guido V, Tubaro M, et al. Effects of atorvastatin 80 mg daily early after onset of unstable angina pectoris or non-Q-wave myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol 2002;90:872-4. 43. Schwartz GG, Olsson AG, Ezekowitz MD, et al. Effects of atorvastatin on early recurrent ischemic events in acute coronary syndromes: the MIRACL study: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2001;285:1711-8. 44. Szummer K, Lundman P, Jacobson SH, et al. Influence of renal function on the effects of early revascularization in non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction: data from the Swedish Web-System for Enhancement and Development of Evidence-Based Care in Heart Disease Evaluated According to Recommended Therapies (SWEDEHEART). Circulation 2009;120:851-8. 45. de Winter RJ, Windhausen F, Cornel JH, et al. Early invasive versus selectively invasive management for acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med 2005;353:1095-104. 46. Bauer T, Koeth O, Junger C, et al. Effect of an invasive strategy on in-hospital outcome in elderly patients with non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J 2007;28:2873-8. 47. Bach RG, Cannon CP, Weintraub WS, et al. The effect of routine, early invasive management on outcome for elderly patients with non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes. Ann Intern Med 2004;141:186-95. 48. Gurvitch R, Lefkovits J, Warren RJ, et al. Clinical outcomes of drug-eluting stent use in patients with ST elevation myocardial infarction. Int J Cardiol 2010;143:283-8. 49. Steg PG, Fox KA, Eagle KA, et al. Mortality following placement of drug-eluting and bare-metal stents for ST-segment elevation acute myocardial infarction in the Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events. Eur Heart J 2009;30:321-9. 50. Diaz de la Llera LS, Ballesteros S, Nevado J, et al. Sirolimus-eluting stents compared with standard stents in the treatment of patients with primary angioplasty. Am Heart J 2007;154:164 e1-6. 51. Kelbaek H, Thuesen L, Helqvist S, et al. Drug-eluting versus bare metal stents in patients with st-segment-elevation myocardial infarction: eight-month follow-up in the Drug Elution and Distal Protection in Acute Myocardial Infarction (DEDICATION) trial. Circulation 2008;118:1155-62. 52. Stone GW, Lansky AJ, Pocock SJ, et al. Paclitaxel-eluting stents versus bare-metal stents in acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 2009;360:1946-59. 53. van der Hoeven BL, Liem SS, Jukema JW, et al. Sirolimus-eluting stents versus baremetal stents in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: 9-month angiographic and intravascular ultrasound results and 12-month clinical outcome results from the MISSION! Intervention Study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2008;51:618-26. 54. Valgimigli M, Campo G, Percoco G, et al. Comparison of angioplasty with infusion of tirofiban or abciximab and with implantation of sirolimus-eluting or uncoated stents for acute myocardial infarction: the MULTISTRATEGY randomized trial. JAMA 2008;299:1788-99. 55. Laarman GJ, Suttorp MJ, Dirksen MT, et al. Paclitaxel-eluting versus uncoated stents in primary percutaneous coronary intervention. N Engl J Med 2006;355:1105-13. 26 56. Chechi T, Vittori G, Biondi Zoccai GG, et al. Single-center randomized evaluation of paclitaxel-eluting versus conventional stent in acute myocardial infarction (SELECTION). J Interv Cardiol 2007;20:282-91. 57. Menichelli M, Parma A, Pucci E, et al. Randomized trial of Sirolimus-Eluting Stent Versus Bare-Metal Stent in Acute Myocardial Infarction (SESAMI). J Am Coll Cardiol 2007;49:1924-30. 58. Spaulding C, Henry P, Teiger E, et al. Sirolimus-eluting versus uncoated stents in acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 2006;355:1093-104. 59. Witt BJ, Jacobsen SJ, Weston SA, et al. Cardiac rehabilitation after myocardial infarction in the community. J Am Coll Cardiol 2004;44:988-96. 60. Sivarajan ES, Bruce RA, Lindskog BD, Almes MJ, Belanger L, Green B. Treadmill test responses to an early exercise program after myocardial infarction: a randomized study. Circulation 1982;65:1420-8. 61. Vermeulen A, Lie KI, Durrer D. Effects of cardiac rehabilitation after myocardial infarction: changes in coronary risk factors and long-term prognosis. Am Heart J 1983;105:798-801. 62. Dorossiev D. Rehabilitation and Comprehensive Secondary Prevention after Acute Myocardial Infarction. Report on a Study. Copenhagen: World Health Organization; 1983. 63. Fridlund B, Hogstedt B, Lidell E, Larsson PA. Recovery after myocardial infarction. Effects of a caring rehabilitation programme. Scand J Caring Sci 1991;5:23-32. 64. Oldridge N, Guyatt G, Jones N, et al. Effects on quality of life with comprehensive rehabilitation after acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol 1991;67:1084-9. 65. Comparison of a rehabilitation programme, a counselling programme and usual care after an acute myocardial infarction: results of a long-term randomized trial. P.RE.COR. Group. Eur Heart J 1991;12:612-6. 66. DeBusk RF, Miller NH, Superko HR, et al. A case-management system for coronary risk factor modification after acute myocardial infarction. Ann Intern Med 1994;120:7219. 67. Marchionni N, Fattirolli F, Fumagalli S, et al. Improved exercise tolerance and quality of life with cardiac rehabilitation of older patients after myocardial infarction: results of a randomized, controlled trial. Circulation 2003;107:2201-6. 68. Kalarus Z, Lenarczyk R, Kowalczyk J, et al. Importance of complete revascularization in patients with acute myocardial infarction treated with percutaneous coronary intervention. Am Heart J 2007;153:304-12. 69. Di Mario C, Mara S, Flavio A, et al. Single vs multivessel treatment during primary angioplasty: results of the multicentre randomised HEpacoat for cuLPrit or multivessel stenting for Acute Myocardial Infarction (HELP AMI) Study. Int J Cardiovasc Intervent 2004;6:128-33. 70. Politi L, Sgura F, Rossi R, et al. A randomised trial of target-vessel versus multivessel revascularisation in ST-elevation myocardial infarction: major adverse cardiac events during long-term follow-up. Heart 2010;96:662-7. 71. Ottervanger JP, Armstrong P, Barnathan ES, et al. Association of revascularisation with low mortality in non-ST elevation acute coronary syndrome, a report from GUSTO IV-ACS. Eur Heart J 2004;25:1494-501. 27