3520-10-updated 2012

advertisement

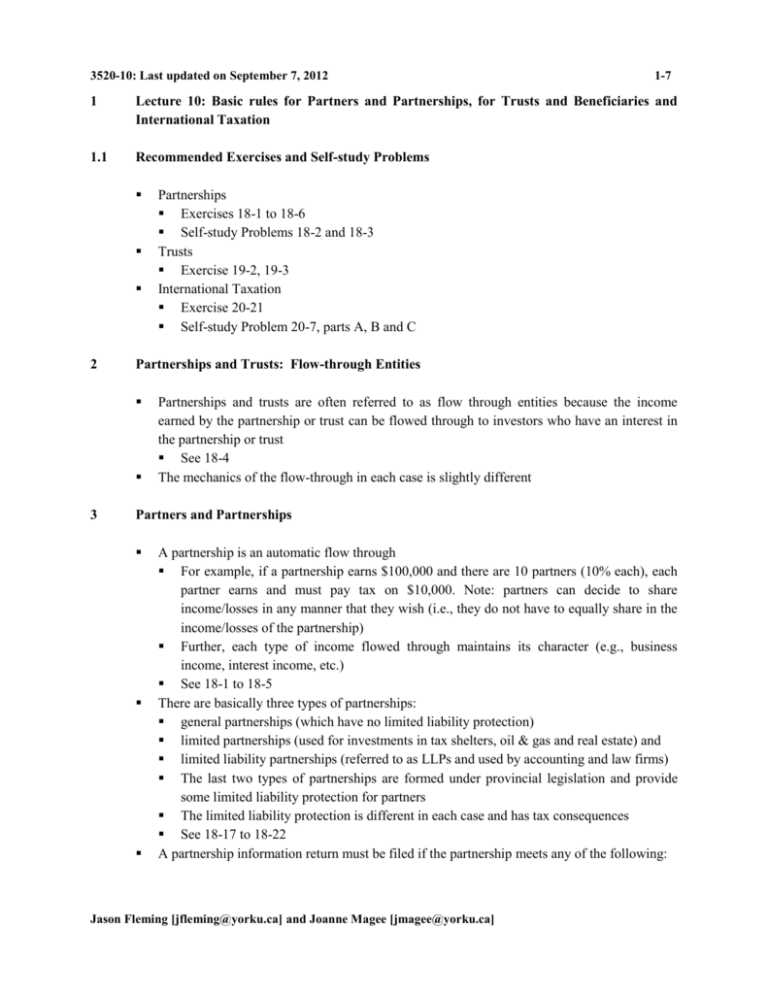

3520-10: Last updated on September 7, 2012 1-7 1 Lecture 10: Basic rules for Partners and Partnerships, for Trusts and Beneficiaries and International Taxation 1.1 Recommended Exercises and Self-study Problems 2 Partnerships and Trusts: Flow-through Entities 3 Partnerships Exercises 18-1 to 18-6 Self-study Problems 18-2 and 18-3 Trusts Exercise 19-2, 19-3 International Taxation Exercise 20-21 Self-study Problem 20-7, parts A, B and C Partnerships and trusts are often referred to as flow through entities because the income earned by the partnership or trust can be flowed through to investors who have an interest in the partnership or trust See 18-4 The mechanics of the flow-through in each case is slightly different Partners and Partnerships A partnership is an automatic flow through For example, if a partnership earns $100,000 and there are 10 partners (10% each), each partner earns and must pay tax on $10,000. Note: partners can decide to share income/losses in any manner that they wish (i.e., they do not have to equally share in the income/losses of the partnership) Further, each type of income flowed through maintains its character (e.g., business income, interest income, etc.) See 18-1 to 18-5 There are basically three types of partnerships: general partnerships (which have no limited liability protection) limited partnerships (used for investments in tax shelters, oil & gas and real estate) and limited liability partnerships (referred to as LLPs and used by accounting and law firms) The last two types of partnerships are formed under provincial legislation and provide some limited liability protection for partners The limited liability protection is different in each case and has tax consequences See 18-17 to 18-22 A partnership information return must be filed if the partnership meets any of the following: Jason Fleming [jfleming@yorku.ca] and Joanne Magee [jmagee@yorku.ca] 3520-10: Last updated on September 7, 2012 3.1 2-7 1) Its revenues plus its expenses exceed $2M (i.e., revenues and expenses are added together); for example, if revenue is $1.3M and expenses are $1M then this requirement is met since $1.3M + $1M is greater than $2M; 2) It has more than $5M in assets; or 3) It has a corporation or a trust as a partner Prior to 2011 a partnership information return had to be filed if the partnership had > 5 partners (i.e., the 3 points above did not apply before 2011) This information return is not a tax return This is an information return similar to one filed for T4s Each partner then gets a slip which sets out his or her share of the partnership income Allocations to Partners and Partner Expenses [ITA 96] The partnership computes its Division B net income as if it were a taxpayer (even though it is not a taxpayer) Each partner is allocated a % of this Division B net income of the partnership and must pay tax on this income (whether or not they receive it) The income is added to the ACB of the partner’s “partnership interest”. The partnership interest is a capital property and it represents the partner’s ownership interest in the partnership When partners actually take money out of the partnership it is called a “draw” or “drawing” (because it is generally a withdrawal of cash) Draws are not taxed because the income is taxed as it is earned Instead, the draw reduces the ACB of the partner’s partnership interest Most deductions are claimed at the partnership level This includes discretionary deductions (such as CCA and reserves) The partnership must decide on the amount and will usually claim the maximum amount of CCA There are a few items computed at the “partner” level rather than by the entire “partnership” Here is a list of the five most common items: Dividends from taxable Canadian corporations earned in the partnership are allocated (and it keeps its form) to the partners they are grossed up and have dividend tax credits in the hands of individual partners or are eligible for ITA 112 deduction in the hands of a corporate partner Business-related expenses which are paid by the partner rather than the partnership can be deducted as a business expense (and are eligible for a GST/HST rebate) Common examples are auto expenses, promotion, meals & entertainment, etc. Losses (non capital losses, net capital losses, etc.) incurred in the partnership are allocated (and keep their form) to the partners Charitable donations made by the partnership (e.g. if the XYZ partnership contributes to the United Way). A 10% partner would be able to claim a donation = 10% of the amount donated Jason Fleming [jfleming@yorku.ca] and Joanne Magee [jmagee@yorku.ca] 3520-10: Last updated on September 7, 2012 3-7 3.2 Partnership Interest 3.2.1 an individual partner would get a credit under ITA 118.1 for his/her 10% share of the donation a corporate partner would gets a deduction under ITA 110.1(1)(a) for its 10% share of the donation Federal political contributions made by the partnership. The partners would be able to claim a political tax credit under ITA 127(3) for their % share of the political contribution. Note: corporations and unions are no longer allowed to make federal political contributions Note: for charitable donations and federal political contributions the ACB of a partner’s partnership interest is reduced by the partner’s % share of any charitable donation or political donation made by the partnership It is useful to think of this as a “non-cash” draw Instead of cash, the partner gets a donation to claim on the partner’s tax return See 18-37 to 18-56 ACB of partnership interest (= partner's equity in a partnership for tax purposes) In an uncomplicated situation, the ACB of a partnership interest is partner’s initial cost + partner’s share of income of the partnership - partner’s share of losses of the partnership - drawings by the partner But there are complications requiring extra adjustments for certain tax-free amounts to maintain integration (so that income earned tax-free to the partnership can be received taxfree by the partner). That is, the ACB is increased for the full amount of a capital gain (CG) and profit on the sale of eligible capital property (ECP) (and similarly decreased for the full amount of a capital loss, CL) for tax free capital dividends and the tax-free profit when life insurance proceeds are received (life insurance proceeds minus the ACB of the policy; note: the ACB is zero for simple life insurance, hence life insurance proceeds are typically received tax free) See 18-64 to 18-66 and 18-74 to 18-82 ITA 53 Rules (ACB of partnership interest) When these complications are added, we get the technical ITA 53 rules for calculating the ACB of partnership interest = Original cost of the partnership interest plus ITA 53(1)(e) adjustments: Income computed on the basis that: CG and CL and gains on eligible capital property (ECP) are computed on a 100% basis non-taxable capital dividends and life insurance proceeds are included Capital contributions Jason Fleming [jfleming@yorku.ca] and Joanne Magee [jmagee@yorku.ca] 3520-10: Last updated on September 7, 2012 3.2.2 there is no immediate CG (ITA 40(3)(a)) unless the interest has been disposed of it is a residual interest in a partnership (e.g. the interest of a retired partner) or the partner is a limited partner of a limited partnership (not an LLP) How could the ACB of a partnership interest be negative? Answer If the partner’s share of losses and/or draws exceeds contributions and/or income Is Interest expense incurred to purchase a partnership interest is deductible? Answer Yes, as long as the partnership is earning income from business or property, all other conditions in ITA 20(1)(c) are met and no other provision of the Act applies to stop the deduction Admission of new partner and withdrawal of a partner 3.3 Other (not covered in this course) minus ITA 53(2)(c) and (o) adjustments: Losses computed on the same basis as above Drawings (including partner salaries) Other (investment tax credits, foreign tax credits, charitable and political donations allocated) If the ACB of a partnership interest is negative at any point/ Interest Expense 3.2.3 4-7 see example in CTP 18-67 to 18-71 If a new partner is admitted to the partnership the price paid by the new partner to acquire his/her partnership interest is the initial adjusted cost base (ACB) of his/her partnership interest. The new partner may buy out an existing partner’s partnership interest or he/she may contribute assets to the partnership If a partner leaves the partnership, the partner typically will sell his/her partnership interest (to a new partner or to the partnership) in return for proceeds of disposition (P of D). If the P of D exceeds the (former) partner’s ACB of his/her partnership interest the (former) partner will have a capital gain. If the P of D is less than the (former) partner’s ACB of his/her partnership interest the (former) partner will have a capital loss Partnerships and Tax Planning There are complications to using partnerships for tax planning. Here are some reasons: Partnerships with an individual as a partner must have a December 31 year-end The 2011 Budget has made changes that affect corporations who are members of a partnership Certain corporate partners will no longer be able to defer income earned through a partnership. These changes are discussed in ADMS 4562 Jason Fleming [jfleming@yorku.ca] and Joanne Magee [jmagee@yorku.ca] 3520-10: Last updated on September 7, 2012 4 The CRA has the power to reallocate partnership income if the allocation was made to defer or reduce income tax payable [ITA 103(1)] or if it is to make an allocation between non-arm’s length partners (e.g. spouses or siblings) more reasonable [ITA 103(1.1)] Attribution rules The attribution rules obviously apply to property income (e.g., interest, dividend, rental income) and capital gains (in the case of spouses) earned through a partnership But business income earned through a partnership is deemed to be property income for the purposes of the attribution rules if the partner is a limited partner or not actively engaged in the business [ITA 96(1.8)] This deeming rule was introduced when it became popular to loan spouses and minors money to invest in partnerships that owned nursing homes and hotels Trusts 4.1 5-7 Trusts are used to separate control over assets (which is in the hands of the "trustee") over beneficial ownership (which the "beneficiaries" have) The fact that trusts separate beneficial ownership from control gives trusts many practical uses because the beneficiaries of the trust do not have control over the trust property What is a trust? A trust is created by a settlor who establishes a trust with initial trust capital. The terms of the trust are set out in a signed trust document (also called a trust deed) (in the case of a testamentary trust, the trust is set out in a will) The trust document sets out what capital settles the trust, who will run the trust (the trustees), who the trust is for (the beneficiaries) & (possibly) when income and capital is to be paid to the beneficiaries. If the trustee gets to decide when and how much income and/or capital of the trust is distributed to the beneficiaries the trust is a discretionary trust. If the trust document determines when and how much income and/or capital of the trust is distributed to the beneficiaries the trust is non-discretionary A beneficiary who is entitled to the income (or a portion of the income) of a trust has an income interest in a trust. Capital gains realized in the year are considered income for Canadian tax purposes A beneficiary who is entitled to the capital property (i.e., the assets) or a portion of the capital property of a trust has a capital interest in a trust. A beneficiary can have both an income and a capital interest in a trust If trust property is paid out to a capital beneficiary the transfer typically occurs on a tax-free rollover basis (i.e., it transfers at tax cost) See Fig. 19-1 See 19-8 to 19-15 Jason Fleming [jfleming@yorku.ca] and Joanne Magee [jmagee@yorku.ca] 3520-10: Last updated on September 7, 2012 4.2 How do Trusts compare to Partnerships as flow-through entities? [ITA 104] 4.3 6-7 Trusts are not complete flow-throughs Income earned by a trust is taxed in the trust unless it is paid or payable to beneficiaries see Fig. 19-3 see 19-39 Losses incurred by a trust do not flow-through (the trust must keep the loss and the trust can carry back or forward the loss just like an individual) Unlike partnerships, trusts are taxpayers and file returns (T3 returns) and pay tax (if they retain any income). The returns are due 90 days after year-end Certain types of income can retain their source in the beneficiaries' hands if they are so designated by the trust but it is not automatic: designations must be made in the trust's T3 return and T3 slips. A designation means that the amount appears in special boxes on the beneficiary's T3 slip. These designations are optional but are usually done because it helps the beneficiary pay less tax e.g. Taxable dividends from taxable Canadian corporations (this allows an individual beneficiary to gross up the dividend & get a dividend tax credit) Net capital gains (1/2 taxable) Net capital gains eligible for the QSBC capital gains exemption Foreign income and foreign tax paid (beneficiary gets a foreign tax credit) and some others Other amounts [e.g. interest income and business income allocated to an individual is just property income under ITA 12(1)(m)] and appears in the other income box of the T3 slip Testamentary vs. Inter Vivos Trusts [ITA 108] A testamentary trust is established on death and usually in a will. An inter vivos trust is established during a lifetime Why do we care about the distinction? Inter vivos trusts must have a calendar year end and are subject to tax at the top marginal rate (without any personal tax credits) whereas testamentary trusts can have any year-end (often the anniversary of death to defer tax) and are subject to the graduated personal tax rates (without any personal credits) If any person other than the deceased settlor transfers property to a testamentary trust it will become an inter vivos trust On the date that is 21 years after the date of creation of a trust (and every 21 years thereafter) the trust is deemed to dispose of and reacquire its capital assets at fair market value. This ensures that accrued capital gains are triggered (at least every 21 years). Jason Fleming [jfleming@yorku.ca] and Joanne Magee [jmagee@yorku.ca] 3520-10: Last updated on September 7, 2012 5 Some trusts will transfer the capital property out of the trust to a capital beneficiary prior to this 21 year deadline (to avoid this deemed disposition) see 19-28 to 19-36 see 19-60 to 19-63 on 21-year deemed disposition rule see 19-113 to 19-118 on income attribution rules International Taxation 5.1 7-7 Residents of Canada are taxed on their worldwide taxable income in Divisions B and C [ITA 2(1)] and non-residents are taxed on certain Canadian source taxable income in Division D if they were employed in Canada, carried on a business in Canada, or disposed of a taxable Canadian property (e.g., Canadian real estate) at any time in the year or a previous year [ITA 2(3)] In order to avoid tax leakage, the ITA contains various rules that deem trusts and corporations owned by Canadians to be resident in Canada and deem certain types of offshore income to be taxed in Canada on an accrual (earned) basis see 20-46, 20-50, 20-55 Foreign Investment Reporting Requirements [ITA 233.3] In order to ensure that Canadians are reporting their offshore income as required under the ITA, corporations and individuals may be required to file a schedule of foreign investments with their tax return The foreign reporting requirements for individuals are as follows: if you hold income earning foreign property with cost > $100,000 at any time in the tax year you must file a Form T1135 the types of foreign property that must be reported = income-earning property (not personal use property) = money, shares, bonds, real estate (personal use property such as a vacation home does not count), mutual funds, partnership interest, patents and copyrights see 20-135 to 20-140 Example If you own U.S. shares but the shares are physically in Toronto, you still must report them Since CRA will have information on their foreign investments, individuals will be more likely to report the foreign income on their Canadian tax returns Jason Fleming [jfleming@yorku.ca] and Joanne Magee [jmagee@yorku.ca]