llm_pre_pap3_bl2 - Madhya Pradesh Bhoj Open University

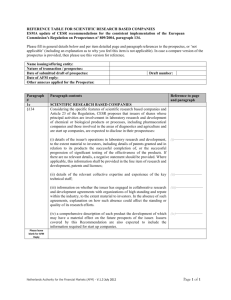

advertisement