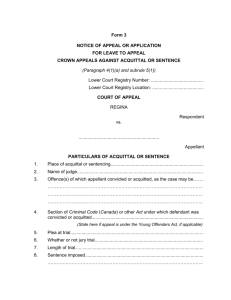

court of criminal appeals, 9-11-02

advertisement