Review notes Ia: Chapter 1 Frank and Bernanke

advertisement

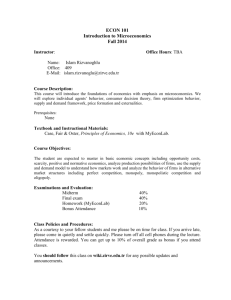

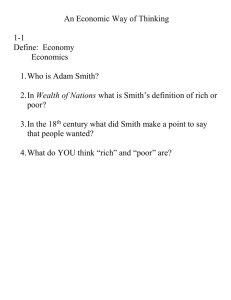

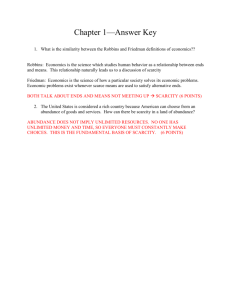

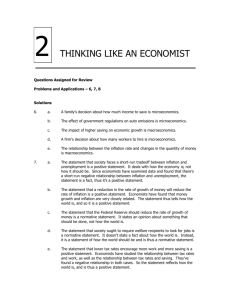

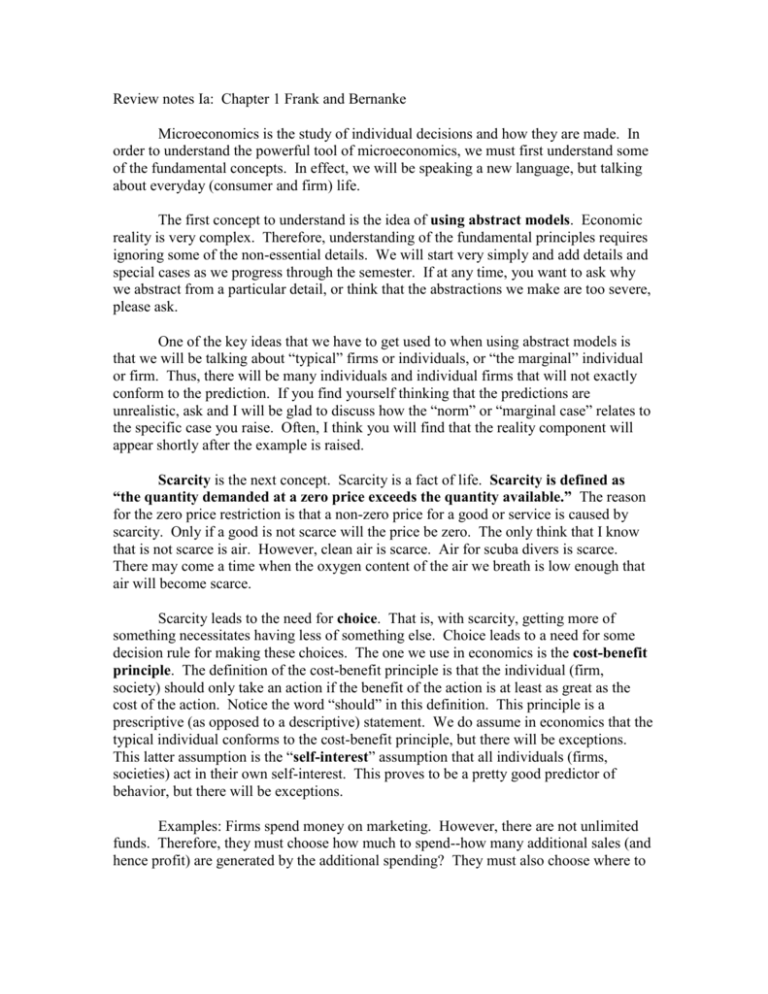

Review notes Ia: Chapter 1 Frank and Bernanke Microeconomics is the study of individual decisions and how they are made. In order to understand the powerful tool of microeconomics, we must first understand some of the fundamental concepts. In effect, we will be speaking a new language, but talking about everyday (consumer and firm) life. The first concept to understand is the idea of using abstract models. Economic reality is very complex. Therefore, understanding of the fundamental principles requires ignoring some of the non-essential details. We will start very simply and add details and special cases as we progress through the semester. If at any time, you want to ask why we abstract from a particular detail, or think that the abstractions we make are too severe, please ask. One of the key ideas that we have to get used to when using abstract models is that we will be talking about “typical” firms or individuals, or “the marginal” individual or firm. Thus, there will be many individuals and individual firms that will not exactly conform to the prediction. If you find yourself thinking that the predictions are unrealistic, ask and I will be glad to discuss how the “norm” or “marginal case” relates to the specific case you raise. Often, I think you will find that the reality component will appear shortly after the example is raised. Scarcity is the next concept. Scarcity is a fact of life. Scarcity is defined as “the quantity demanded at a zero price exceeds the quantity available.” The reason for the zero price restriction is that a non-zero price for a good or service is caused by scarcity. Only if a good is not scarce will the price be zero. The only think that I know that is not scarce is air. However, clean air is scarce. Air for scuba divers is scarce. There may come a time when the oxygen content of the air we breath is low enough that air will become scarce. Scarcity leads to the need for choice. That is, with scarcity, getting more of something necessitates having less of something else. Choice leads to a need for some decision rule for making these choices. The one we use in economics is the cost-benefit principle. The definition of the cost-benefit principle is that the individual (firm, society) should only take an action if the benefit of the action is at least as great as the cost of the action. Notice the word “should” in this definition. This principle is a prescriptive (as opposed to a descriptive) statement. We do assume in economics that the typical individual conforms to the cost-benefit principle, but there will be exceptions. This latter assumption is the “self-interest” assumption that all individuals (firms, societies) act in their own self-interest. This proves to be a pretty good predictor of behavior, but there will be exceptions. Examples: Firms spend money on marketing. However, there are not unlimited funds. Therefore, they must choose how much to spend--how many additional sales (and hence profit) are generated by the additional spending? They must also choose where to spend it—more money spent on TV means less available for print media. Where is the greatest return? The criterion, or measure, of economic success used in this simplest of models is economic surplus. This is the excess of benefit over cost of a given action. For example, if you buy a car for less than you would have been willing to pay for it, there is an economic surplus. In this case you are better off after the purchase than before, and therefore, you improved your self-interest by making the purchase. One of the more difficult to fully understand, but also more important concepts included in chapter one of Frank and Bernanke (FB) is opportunity cost. This is value of the next best activity given up when an activity is undertaken. For example, if I buy a Quarter Pounder in McDonalds, I choose not to buy a Big Mac. If the Big Mac is thing I would have bought with the money I used for the Quarter Pounder, then the opportunity cost of the Quarter Pounder is the Big Mac. Another example is when you choose to take one job, you simultaneously choose to not take another (the opportunity cost). When I open my own business, I give up the opportunity to work for someone else for a salary. (This example says that when I decide whether the new firm is a profitable undertaking, I need to take the lost salary (opportunity cost of my use of my time in the new firm) into account.) If I keep a stock, I do not have the use of the funds to invest in something else. Four Pitfalls are listed in FB. 1. Measuring costs and/or benefits proportionally rather than in absolute amounts. One example of this in business would the attention to market share rather than profit. Many marketers assume that consumers do use relative measures rather than absolute measures. Otherwise, rebates, “cash back,” etc. would not be as common as they are. 2. Ignoring opportunity costs. This is most common in evaluation of the use of resources (especially time). What is the alternative given up? That is the relevant question. 3. Failure to ignore sunk costs. Sunk costs are those that do not change with the decision. If you invest money in a stock, your decision whether to sell should be based upon its future value, not its initial cost. The former is affected by the decision, the latter is not. 4. Failure to understand the average-marginal distinction. When you go to work, the decision is not whether to work, it is how much to work. This is a marginal decision. Adding employees is based upon the additional value of the additional worker, not the average value of all workers. In this module we will be looking at microeconomics. This relates to the decisions of individuals and individual firms. Next module you will cover macroeconomics that deals with the aggregate economic activity (economies, international economics, etc.). The general orientation will be “if it is useful, we will talk about it, if it is not, we won’t.” So if you find times when you do not see the relevance of what we are talking about, let me know. We will either move to other topics or I will relate the current topic to the reality of the firm or consumer. In general, the overall goal will be to be able to make better firm decisions. Pricing will be the topic of the second half of the course. One pair of concepts are important for our analysis that are not covered in the book. This is Normative vs Positive. A normative statement is a statement which includes an opinion. A positive statement is a statement of fact or verifiable analysis. The reason this pair of concepts is important is that economists agree on most positive statements that I and Dr. Sedgley will cover in this and the next course. However, economists often disagree about normative issues. Example: “There is a tradeoff in the short run between inflation and unemployment” is a positive statement. It is verifiable (one can test it, using facts). It does not include a value statement about which is more important. “We should decrease the unemployment rate” is a normative statement. It includes the word “should” which implies a value statement. You an I may disagree about this, as we might put more or less emphasis on the consequences of decreasing the unemployment rate. If the decrease in the unemployment rate were free (without cost), we would probably agree, but it is not free (see Chapter 2 discussions). Most of the issues we will be talking about will be positive issues. However, we will be doing some prescription (hence, normative analysis) in microeconomics when we talk about the best policies, especially when we get to the pricing section of the course. Most of the descriptive analysis in the course will be positive. Be careful when using economics to keep the normative and positive clearly separated (or at least identified in your mind). Most arguments about economics are over normative issues, although they may be phrased “You are wrong.” With positive economic statements, one can be determined to be right or wrong. With normative statements, there is often no right or wrong, just differences of opinion. (ex. Which is a more important problem, inflation or unemployment?)