Conceptual Framework Document

advertisement

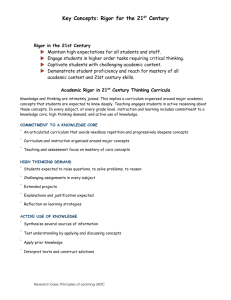

Arkansas Tech University Unit of Education – Conceptual Framework “Professionals of the 21st Century” Our Vision: Students are “Professionals of the 21st Century” who will internalize, initiate, and sustain a professional commitment to impact learners in diverse and evolving learning communities. Our Mission: The mission of our Educational Unit at Arkansas Tech University is to positively impact student learning by educating, sustaining, and nurturing professionals who interact within dynamic educational systems through research-, performance-, and standards-based preservice and graduate education programs. We will do this by modeling best practices, by being committed to continuous learning and purposeful reflection, and by working collaboratively with internal and external constituencies. This mission statement is directly aligned with the mission of Arkansas Tech University. Excerpts from the mission statement of Arkansas Tech University are included below (The statement may be viewed at http://www.atu.edu/about.shtml.). Mission Statement--Arkansas Tech University a state-supported institution of higher education, is dedicated to nurturing scholastic development, integrity, and professionalism. The University offers a wide range of traditional and innovative programs which provide a solid educational foundation for life-long learning to a diverse community of learners. The mission of the unit is founded upon a set of core values, which, in turn drive the conceptual framework, which guides the development of programs and the delivery of courses within each program. The core values are born of our consideration for our goal of excellence in teaching, which is related to the “primary” function of Arkansas Tech University; the examination of established national, state, and unit standards for teaching and learning; and the review of curriculum experiences and expectations in all programs with a vision of “impacting learners in diverse learning communities.” Our Philosophy, Purposes, and Goals: The Educational Unit at Arkansas Tech University provides several undergraduate and graduate professional education programs designed to positively impact student learning through the preparation of Professionals of the 21st Century. Due to the variety of programs offered to accomplish this mission, the Educational Unit has actively, consistently, and collaboratively worked with a variety of stakeholders in the learning community to determine what our core values should be to anchor the unit, the expression of these core values in our vision and mission, the programs within the unit, and the assessment throughout. We believe these core values to be central in our vision of “impacting learners in diverse learning communities” and in preparing Professionals of the 21st Century to do just that. These core values are lasting beliefs that when adopted by our students as their own will assist our graduates in becoming “professionals who interact effectively within dynamic educational systems to impact learners in those diverse learning communities.” The core values are the context for how professional, state, and institutional standards are addressed within the programs as we prepare Professionals of the 21st Century. The core values direct the development and refinement of programs, courses, design of instruction, research, service, and assessment. Our assessment of student learning (both of our students and the students they work with) then drives the process in the other direction to assist us in improving each of the aforementioned factors and in revisiting and/or the reconsideration of the outworking of these core values within our students. The core values include the following statements of belief: 1. All human beings grow, develop, and learn. 2. Educational processes have discipline-specific key components. 3. Educational practices are systemically coherent and developmentally appropriate to produce a quality P-20 community. 4. Educators are moral and ethical professionals that are contributing members of the educational community. 5. Educators focus on maximizing growth, development, and learning opportunities for all students. 6. Educators continually assess student learning outcomes. Founded upon these core values our mission, vision, and conceptual framework – Professionals of the 21st Century, have been developed. The framework emphasizes the Professional of the 21st Century as a continuously learning individual with a strong and developing knowledge of school systems and culture; with an increasing level of content and pedagogical knowledge, skills, and dispositions; with a strong and growing liberal arts background; and with growing expertise concerning developmentally appropriate practices. As candidates progress through their undergraduate preparation and as they then pursue their graduate preparation, these areas of expertise are expected to grow. Ultimately, this preparation is centered-upon the improvement of student learning. This framework agrees with the expressed mission of Arkansas Tech University. By considering our students as life-long learners (continuous learning professionals), and by assessing our students’ knowledge and skills carefully and consistently, the mission of Arkansas Tech University and the mission and vision of the Arkansas Tech University Education Unit are aligned. Further, the fulfillment of our mission by modeling best practices, by being committed to continuous learning and purposeful reflection, and by working collaboratively with internal and external constituencies not only serves in the preparation of our candidates as Professionals of the 21st Century but improves our teaching and learning environments as well, which are main functions of Arkansas Tech University. To summarize, the Professional of the 21st Century is a continuously learning expert with a(n): Increasing Level of Content and Pedagogical Knowledge, Skills, and Dispositions; Strong and Growing Liberal Arts Background; Growing Expertise Concerning Developmentally Appropriate Practices; and Strong and Developing Knowledge of School Systems and Culture. These four foundations are unified through the following factors: Diversity Leadership Oral and Written Communication Technology Purposeful Reflection Parents and Community In other words a strong and developing knowledge of school systems and culture should include the understanding of the diversity within the school systems and culture, leadership structures and processes within the school systems and culture, the key role of technology in the school systems and culture, and so forth. An increasing level of content and pedagogical knowledge, skills, and dispositions should include emphasis upon issues of diversity, technology, oral and written communication, and so forth. The emphasis of these same unifying aspects throughout each of the four foundations of the conceptual framework is present and is evidenced in each separate program that seeks to prepare Professionals of the 21st Century. As our candidates progress through each program (undergraduate through graduate) their expertise in these aforementioned unifying forces and foundations should continually grow. These key unifying forces and the aforementioned four foundations are evidenced in each program via the particular program standards and the assessments of our students based upon the program alignment with these respective standards. For example in the undergraduate teacher education program, the Arkansas Standards/Principles for Beginning Licensure and the Pathwise Criteria (both of which are founded upon the INTASC Standards) along with the National Education Technology Standards adopted by the Arkansas State Department of Education are considered the Benchmarks from which we determine whether or not our students have: 1.) Adopted the core values evidenced in the conceptual framework, 2.) Provided appropriate evidence to demonstrate their expertise concerning the four foundational aspects of the framework, and 3.) Provided sufficient evidence to demonstrate an expertise concerning the aforementioned unifying aspects. In alignment with our ultimate focus, which is Student Learning, the INTASC-based standards and criteria provide benchmarks for determining if we are preparing Professionals of the 21st Century who are capable of impacting learners in diverse learning communities and who, when actually practicing in diverse learning communities; have a positive impact on student learning. In addition to the Arkansas Standards for Beginning Licensure, Pathwise Criteria, and National Educational Technology Standards used as benchmarks in the undergraduate teacher education programs, undergraduate programs also use national standards from their respective program areas as benchmark indicators. For instance the Middle Level Program uses the aforementioned standards and criteria as well as the National Middle School Association standards as benchmarks in the development of the Middle Level Program and in the assessment of candidates within the program. In graduate programs such as the Master of Education in Teaching, Learning, and Leadership, for example, the National Board for Professional Teaching Standards (NBPTS) and Interstate School Leaders Licensure Consortium (ISLLC) are used as benchmarks. In addition the program uses the Arkansas Curriculum Program Administrator Standards and appropriate National Educational Technology Standards as benchmarks of their candidates’ progress. Each undergraduate and graduate program is standards-based in the development and refinement of programs, courses, design of instruction, and assessment. In summary the Arkansas standards and Pathwise Criteria serve as the basic benchmarks for program development, student assessment, etc. Further benchmarks are developed through the examination and alignment of programs with their respective national standards. Based upon this alignment to state and national standards, the Arkansas Tech University Education Unit has three primary goals: Our Professionals of the 21st Century will meet and/or exceed the standards of the State of Arkansas and the respective national standards for their particular program of studies. Our Professionals of the 21st Century will impact learners in diverse and evolving learning communities. We as a faculty will exhibit professionalism by modeling best practices, by being committed to continuous learning and purposeful reflection, and by working collaboratively with internal and external constituencies. There are several knowledge bases that inform our conceptual framework. The work by Danielson (2007) in agreement with the INTASC standards (Interstate New Teacher Assessment and Support Consortium, 1992) and directly aligned to the Pathwise criteria provide the initial support for each of our four foundational areas previously discussed. The importance of each of these four foundational areas connected through the six unifying factors cited previously is strongly established upon a rich theoretical, research, wisdom of practice, and educational policy base. Each of the four foundations with their informing knowledge bases will be briefly reviewed. Knowledge Bases, including Theories, Research, Wisdom of Practice, and Educational Policies: Content and Pedagogical Knowledge, Skills, and Dispositions Overview: One fundamental trait of a Professional of the 21st Century should be an expertise and increasing expertise of professional and pedagogical knowledge, skills, and dispositions. As indicated by the research of Danielson (2007) and other frameworks, professional and pedagogical knowledge, skills, and dispositions should be considered vital characteristics of educational professionals (Carter, 2008-2009; Carter, 2008). In agreement with this assertion, the Arkansas Department of Education has accepted and adopted much of the work of these research efforts in designing the Arkansas Standards for Beginning Licensure and as a basis for specialty licensure in Arkansas. The College of Education at Arkansas Tech University in support of these findings is committed to developing within its Professionals of the 21st Century the content and pedagogical knowledge, skills, and dispositions to assist these professionals in “impacting learners in diverse and evolving learning communities.” Research has consistently verified that content knowledge, communication skills, and intelligence (as measured by traditional intelligence tests) are vitally important, but these alone are not sufficient characteristics of professional educators. Rather research has demonstrated that content and pedagogical knowledge, skills, and dispositions are essential characteristics needed by professional educators to impact learners in diverse and evolving learning communities (Wilson, Floden, FerriniMundy, 2001; Richardson, 2001; Wilson, 2008). Therefore, the Arkansas Tech University Education Unit in its goal of preparing Professionals of the 21st Century deems content and pedagogical knowledge, skills, and dispositions as a critical foundation for our programs. The Unifying Forces of Diversity, Leadership, Oral and Written Communication, Technology, Purposeful Reflection, and Parents and Community in our Content and Pedagogical Knowledge, Skills and Dispositions These content and pedagogical knowledge, skills, and dispositions are benchmarked through the appropriate state and national standards in each program. This emphasis is infused throughout our programs via the aforementioned unifying forces. For instance part of the essential content and pedagogical knowledge, skills, and dispositions preparation involves issues of diversity. As noted by Stronge (2002): The effective teacher truly believes that all students can learn – it is not just a slogan. These teachers also believe that they must know their students, their subject, and themselves, while continuing to account for the fact that students learn differently. Through differentiation of instruction, effective teachers reach their students and together they enjoy their successes (p. 19). Content and pedagogical knowledge, skills, and dispositions as they relate to aspects of diversity are essential in the preparation of Professionals of the 21st Century particularly since current theory and wisdom of practice suggest that students are not “blank slates” to be written upon but who are individuals who bring diverse backgrounds and experiences to the learning community that affect what is learned and how it is learned (Freibert, 2010-2011; Womack, 2004; Woolfolk, 2008). In support of this claim, Putman and Borko (2000) suggest that knowledge of the [diversity of the] learners and of learning itself is the most important knowledge a teacher must possess. In addition these content and pedagogical knowledge, skills and dispositions should include evidence of a growing technological expertise and a commitment to the appropriate use of technology (another unifying factor of the conceptual framework). The International Society for Technology in Education (2002) summarizes this preparation in the following way: Through the ongoing use of technology in the schooling process, students are empowered to achieve important technology capabilities. The key individual in helping students develop those capabilities is the classroom teacher. The teacher is responsible for establishing the classroom environment and preparing the learning opportunities that facilitate students’ use of technology to learn, communicate, and develop knowledge products. Consequently, it is critical that all classroom teachers are prepared to provide their students with these opportunities (p. 4). The Arkansas Tech University College of Education is in agreement with this assertion. Therefore, we seek to prepare Professionals of the 21st Century with the necessary content and pedagogical knowledge, skills, and dispositions as they relate to technology to assist in meeting this identified need. Our Professionals of the 21st Century should also exhibit content and pedagogical knowledge, skills, and dispositions expressed through each of the other unifying factors. Our students should understand that they are part of a larger learning community involving parents, the school community, business/community, etc. Research has confirmed the importance of effective student, parent, and community with professional educator oral and written communication (Danielson, 2007; Lucas, 2007; Osborn & Osborn, 2006; Stronge, 2002). Our candidates and graduates should exhibit the professional knowledge, skills, and dispositions that demonstrate these unifying factors (involvement with parents and community and effective oral and written communication). Therefore an emphasis on effective oral and written communication among various community stakeholders is deemed essential in continuously developing the professional knowledge, skills, and dispositions of our Professionals of the 21st Century (Henniger, 2004; Pathwise Classroom Observation System Orientation Guide, 2002; Stanulis & Ames, 2009). Further, it is essential that our Professionals of the 21st Century continue to improve their ability to purposefully reflect upon the learning of their students by considering student diversity, educational theory, technology use, assessment results, informal feedback, curriculum and instruction, standards attainment, etc. This purposeful reflection is essential in the continuous improvement of the professional. Stronge (2002) suggests: An important facet of professionalism and of effectiveness in the classroom is a teacher’s dedication to students and to the job of teaching. Through examination of several sources of evidence, a dual commitment to student learning and to personal learning has been found repeatedly in effective teachers. A common belief among effective teachers, which reveals their dual commitment, is that it is up to them to provide a multitude of tactics to reach students. In essence, effective teachers view themselves as responsible for the success of their students (p. 19). In preparing Professionals of the 21st Century, this ability to purposefully reflect as a professional must be developed and continuously improved with the goal of “impacting learners in diverse learning communities.” Finally, our Professionals of the 21st Century must be developing experts who consider themselves to be leaders within the learning community (Fullan, 2010, Marzano & Waters, 2009). This is vital for strong learning organizations that have a goal of improving the learning of students (Donaldson, 2001; Fullan, 2001; Senge, et al., 2000). According to Donaldson (2001), “Leadership satisfies a basic function for the group or organization: It mobilizes members to think, believe, and behave in a manner that satisfies emerging organizational needs, not simply their individual needs or wants” (p. 5). Further, Fullan (2001) claims that, “Strong institutions have many leaders at all levels” (p. 134). Therefore in the preparation of individuals who exhibit content and pedagogical knowledge, skills, and dispositions; leadership at increasing levels must be considered (Covey, 2004). For preservice and novice teachers this leadership may be initially evidenced through modeling, advocating, communicating high expectations, and in expressing a commitment to student learning and personal learning (DuFour, Eaker, Dufour, 2008; Donaldson, 2001; McGuire & Rhodes, 2010; Reeves, 2008; Stronge, 2002). This understanding and participation in leadership with and among other stakeholders in the learning organization should be further evidenced through continuing professional development in, for example, our graduate degree programs. According to research findings and applications, this leadership will powerfully influence the goals of the learning organization and ultimately student learning (DuFour, Eaker, & Dufour, 2008; McGuire & Rhodes, 2010; Reeves, 2008; Senge, et al., 2000). Knowledge of School Systems and Culture Overview: A second foundation of the Arkansas Tech University Unit of Education’s conceptual framework is preparing the Professionals of the 21st Century with a growing knowledge of school systems and culture. According to Ryan and Cooper (2007): Cultures, including school cultures, can be good or bad, leading to good human ends or poor ones. A strong, positive school culture engages the hearts and minds of children, stretching them intellectually, physically, morally, and socially. A school with a weak, negative culture may have the same type of physical plant, student-teacher ratio, and curriculum as a neighboring good school, but it may fail to engage students (p. 13). It is important that the Professionals of the 21st Century understand the general aspects of school systems and culture as well as the idiosyncrasies within the particular school system and culture in which she or he will be participating. Further, not only are there general aspects of school culture as well as particular distinguishing characteristics of particular school cultures, but continuous change focused toward impacting student learning is to be expected (Fullan, 2001; Richardson, 2002; Senge, et al., 2000). This includes potential change in instructional approaches, curriculum design, assessment, school leadership, etc. Our candidates enter school systems and culture in which certain aspects are fairly stable (time, classrooms, etc.) and in which change is generally a necessity due to higher standards and external demands (Sparks, 2002). Therefore, Professionals of the 21st Century must have a growing knowledge of the school systems and culture as well as the understanding of the changing dynamics within that culture that the particular system exists (Fullan, 2001; Senge, et al., 2000). As our candidates progress through our undergraduate and graduate programs, this knowledge and understanding should be continuously improving. This emphasis is benchmarked through the state and national standards for each program respectively, and this emphasis is infused throughout our programs via the unifying forces. The Unifying Forces of Diversity, Leadership, Oral and Written Communication, Technology, Purposeful Reflection, and Parents and Community in Our Knowledge of the School Systems and Culture: Our Professionals of the 21st Century should have an understanding of the diversity of the school systems and culture as it relates to students, colleagues, administrators, parents, etc (Danielson, 2007; DuFour, Eaker, & DuFour 2008; Fullan, 2001; Sparks, 2002; Stronge, 2002). This is particularly important since the members of this diverse learning community will be the professional educator’s key partners in “impacting learners in diverse and evolving learning communities (Stronge, 2002). Our Professionals of the 21st Century must also understand the role of leadership at various levels of school systems and culture (DuFour, Eaker, & DuFour, 2008; Fullan, 2001; Reeves, 2008; Senge, et al., 2000). This leadership may involve at particular times and settings a diverse range of leaders with various leadership styles. Our candidates should understand the importance of the endeavor they are pursuing to improve student learning in these learning systems and the necessity of being a leader in their respective context and/or position (DuFour, Eaker, & DuFour, 2008; Fullan, 2001; Hord, Roussin, & Sommers, 2010; Reeves, 2008; Stronge, 2002). Moreover our Professionals of the 21st Century must demonstrate effective oral and written communication skills particularly since school systems and the cultures therein involve such a diverse array of stakeholders and since the teacher is viewed by many as a model of expertise (Rose & Gallup, 2003; Stronge, 2002). According to Rose and Gallup (2003), “The public has high regard for the public schools, wants needed improvement to come through those schools, and has little interest in seeking alternatives” (p. 53). Due to the importance of oral and written communication in the school culture, many experts have established this characteristic as a benchmark for the educational professional (Cooper & Morreale, 2003). The role of collegial and purposeful reflection is also a necessity in every school system and culture. According to Stronge (2002): Effective teachers also work collaboratively with other staff members. They are willing to share ideas and assist other teachers with difficulties. Collaborative environments create positive working relationships and help retain teachers. Additionally, effective teachers volunteer to lead work teams and to be mentors to new teachers. Effective teachers are informal leaders on the cutting edge of reform and are not afraid to take risks to improve education for all students (p. 19). Professionals of the 21st Century must exhibit a continually improving ability to purposefully reflect initially concerning the learning and assessment of their own students, methods, evaluation approaches, and so forth. Next, they must begin to develop this ability in new positions of leadership and to encourage others in the school system and culture to develop and/or improve this ability as well. This purposeful reflection is essential in improving as a professional (Stronge, 2002) and in improving the learning organization (Donaldson, 2006; Donaldson, 2001; Fullan, 2001; Mertler, 2009; Picciano, 2006; Reeves, 2008; Senge, et al., 2000). In addition it is essential for Professionals of the 21st Century to demonstrate an understanding that they are part of a system with an overarching goal of improving student learning (Donaldson, 2001; Morrison, Ross, & Kemp, 2001; Ryan & Cooper, 2007). As Donaldson (2001) has noted, professional educators should view themselves as more than independent and individual beings but instead as part of a larger organization or system. Candidates’ systemic and developmentally appropriate practices should continue to improve as they progress through our undergraduate and graduate education programs. This improvement is evidenced through assessments founded upon respective program-adopted standards. Finally, the role of technology within the school system and culture should be emphasized in the development of our Professionals of the 21st Century. As posited by ISTE (2002) and Baylor (2000), the use of technology is an essential tool in assisting the learning and thinking of learners within the diverse school culture (Picciano, 2006). Due to internal needs and external opportunities/pressures, the use of technology as a communication, learning, assessment, and data management tool will only increase within the respective school system and culture (ISTE, 2002; Ryan & Cooper, 2007). Therefore, our Professionals of the 21st Century need to be prepared with knowledge of technology use currently within the school system and culture in which they participate and the potential for its use in their future educational endeavors. This knowledge should improve over time across their undergraduate and graduate preparation. Developmentally Appropriate Practices Overview: In order to “impact learners in diverse learning communities,” it is essential for Professionals of the 21st Century to demonstrate developmentally appropriate practice. This is necessary due to the diversity of cognitive, physical, and socio-emotional development, as it relates to individual students across multiple grade levels, backgrounds, and experiences (Gestwicki, 2011; Payne, 2001; Rushton & Larkin, 2001). According to Doherty and Bailey (2003), “…knowledge of skill acquisition and development is vital in ensuring that the experiences [of learning] are enjoyable, valuable and will allow children to lead active and full lives” (p.62). The Unifying Forces of Diversity, Leadership, Oral and Written Communication, Technology, Purposeful Reflection, and Parents and Community in Developmentally Appropriate Practices: Much research and wisdom of practice emphasizes various aspects of development (e.g., Cole, 2008; Gordon, & Browne, 2011; Papalia, Olds, & Feldman, 2008). Within this consideration are issues of diversity concerning typical development and development that ranges below or beyond the norm. In classes that are developmentally appropriate (Bredekamp, 2009), teachers are not the one and only source of knowledge; students also actively engage in generating and sharing understanding. The teacher and students together become a learning community in which everyone’s contributions are valued. The consideration of diversity in this description should not be overlooked. In the developmentally appropriate classroom, students are not blank slates but rather developmentally diverse at different grade levels and as individuals. This developmentally appropriate practice will require clear communication with a variety of stakeholders in the learning community. As Gesticki (2001) has noted, this requires the educational community to focus on how we receive additional information about a student’s development. In this goal, oral and written communication with parents and the community is vital (Stronge, 2002). This is particularly true when considering public expectations reinforced by higher national and state learning standards and the assessments based on those standards (Rose & Gallup, 2003; Ryan & Cooper, 2007). As noted by Ryan and Cooper (2007), the benefit of technology as a key tool in improving developmentally appropriate practices should not be underestimated in the preparation of Professionals of the 21st Century. As noted previously, technology may be used with students at a variety of developmental levels and should be used to improve the practice of educational professionals (ISTE, 2002; Morrison, Ross, & Kemp, 2001; Ryan & Cooper, 2007; Picciano, 2006). Finally the role of purposeful reflection concerning systemic and developmentally appropriate practice is considered vital. As Parkay, Anctil, and Hass (2006) have suggested when discussing this practice: We are realizing with increasingly, sophistication that life is organic, not mechanical; the universe is dynamic, not stable; the process of curriculum development is not passive acceptance of steps, but evolves from action within the system in particular contexts; and that goals emerge oftentimes from the very experiences in which people engage. (p. 221). This statement provides an important insight concerning the reflective activity of the improving professional. The professional is aware of the fact that she or he operates within a larger educational system where a variety of approaches in impacting students of varying developmental levels may be used. She or he also makes use of the knowledge of others operating within the system to inform instruction. And, there is an emphasis on the development and the diversity of students within the system as related to instructional design. This sort of reflective activity provides continuous improvement in developmentally appropriate practice within a system (Danielson, 2007; Ryan & Cooper, 2010; Rushton & Larking, 2001). Numerous program and state licensure standards are used as expectations for our candidates to demonstrate these practices. Strong Liberal Arts Background Overview: The fourth foundation needed to “impact learners in diverse and evolving learning communities” is a strong liberal arts background. Research has consistently demonstrated the need for Professionals of the 21st Century to have the knowledge of their content and the ability to understand how to effectively communicate, problem-solve, relate their content to other content, and critically think in order to effectively instruct (Danielson, 2007; Darling-Hammond, 2002; Womack, 2004; Stewart, 2003). In addition, schools are considered by many to have multiple goals and responsibilities within the community (Ryan & Cooper, 2010). These goals include academic, vocational, social and civic, and personal development ends. In recent decades, schools have tried to be all things to all people. According to Ryan & Cooper (2010): The education of America’s children regularly tops the list of the public’s social concerns. Particularly now, in the first decade of the twenty-first century, our educational system is receiving major attention from social critics and politicians because of this high priority, the U.S. teaching force—present and near future—is receiving a good deal of scrutiny. Americans are relying on their teachers to instruct, guide, inspire, motivate, and occasionally prod their children to learn more than ever before. (p. 21). With this phenomenon being noted, it is apparent that our Professionals of the 21st Century must not only understand and be able to effectively teach their content, but they must also be aware of societal, academic, vocational, and personal issues related to school participation. This is particularly important since, according to Vygotsky and more current theorists (Marion, 2011), learning take places within the larger socio-cultural setting. To effectively participate in this profession, our students need a strong liberal arts background in which they contribute as a knowledgeable professional within society. This foundation is in strong agreement with the Arkansas Tech University general education goal statement, which asserts: The basis for the student's intellectual growth and scholarly skill development is the general education program, which provides the context for more advanced and specialized studies and the foundation for life-long learning. The general education curriculum is designed to provide university-level experiences that engender capabilities in communication, abstract inquiry, critical thinking, analysis of data, and logical reasoning; an understanding of scientific inquiry, global issues, historical perspectives, literary and philosophical ideas, and social and governmental processes; the development of ethical perspectives; and an appreciation for fine and performing arts. The Unifying Forces of Diversity, Leadership, Oral and Written Communication, Technology, Purposeful Reflection, and Parents and Community in Our Strong Liberal Arts Background: Various professional organizations have cited the essential need that our Professionals of the 21st Century have the ability to consider the diverse perspectives of their learners (and fellow professionals within their particular field of expertise [e.g., NCTE, 1996; NCTM, 1989]). This diversity includes the way in which particular individuals examine content, communicate within the content, express their background knowledge in the content, etc. Therefore, our Professionals of the 21st Century must have a strong liberal arts background to help them “impact learners in diverse learning communities.” An understanding of the society, expected skills, history, and philosophies of the culture in which the professional will be practicing will allow the professional to be a model of expertise and citizenry that is expected by many in today’s diverse society (Rose & Gallup, 2003). In addition strong leadership understanding and skills are essential in today’s school and society. In order to provide this leadership, Professionals of the 21st Century must have a basis of understanding that is considered expert for their profession and for professionals in general (Donaldson, 2001; Fullan, 2001; Morrison, Ross, & Kemp, 2001; Reeves, 2008). According to Ryan and Cooper (2007): A school system is a bureaucracy whose long arm extends from the state commissioner of education to the local district superintendent of schools to the individual school principal. That long arm is, in fact, educational policy—the ideas that are supposed to direct what happens in a school and, more specifically, in your classroom.” (p. 460). It is important that our Professionals of the 21st Century understand the role of leadership within the society and how they might demonstrate a liberal arts expertise to be considered a leader within the school and community (DuFour, Eaker & DuFour, 2008; Fullan, 2004, Marzano & Waters, 2009). Further, the Professionals of the 21st Century need to demonstrate an ability to effectively communicate through oral and written communication. This ability has been oft cited as a necessary tool of the educational professional (Cooper & Morreale, 2003; Darling-Hammond, 2002). Candidates should be well prepared through their liberal arts training to be effective communicators within the school and community. This is a vital characteristic of Professionals of the 21st Century since they many times provide the model of communication expertise to their students. A strong liberal arts background is also essential to the Professional of the 21st Century due to the constant interaction of the professional with parents and the community. One role of the professional is that of social and civic responsibility (Rose & Gallup, 2003). This role requires the Professionals of the 21st Century to be adept at effectively interacting with a diverse constituency. To accomplish this goal the Professionals of the 21st Century must exhibit basic communication skills, problem-solving abilities, and understanding of social and governmental processes, philosophical ideas, history, etc. The role of technology in developing a strong liberal arts expertise should not be underestimated. The ability to effectively use of technology is not just a “school-building” concern. But as noted by ISTE (2002), “To live, learn, and work successfully in an increasingly complex and information-rich society, students and teachers must use technology effectively” (p.4). The ability to use technology has become essential since much of the information we now use has been created, compiled, and/or presented through some form of advanced technology (Pitler, Hubbell, Kuhn, & Malenoski, 2007; Picciano, 2006; Pitler, Hubbell,& Kuhn). Our students should be models of technology expertise and this expertise should improve as they progress through their initial liberal arts preparation and conclude their respective graduate program preparation. Finally, purposeful reflection plays a key role in the development and improvement of a strong liberal arts background. As students are asked to consider various philosophical ideas, social and governmental processes, historical perspectives, and so forth; they are being asked to reflect on broad generalizations and concepts. This ability should continue to improve as they are asked to purposefully reflect more specifically on classroom learning. The strong liberal arts expert is able to think reflectively and purposefully about the content, diversity of student thought and background, underlying larger rationales for learning new content and/or skills, etc (Henniger, 2004; Wilson, 2008; Stewart. 2003). The liberal arts background that includes historical perspectives, governmental processes, philosophical perspectives, etc should improve as our Professionals of the 21st Century continue through our undergraduate and graduate preparation programs. For instance as our candidates are asked to specifically consider governmental processes directing much of the efforts of education (such as No Child Left Behind), they are becoming more knowledgeable in their liberal arts background. As they consider the societal situations and conditions that led to many of the current theories of learning, their liberal arts background is improving. This is an ongoing and unending life-long learning pursuit that has been included in the “life-long” learning standards communicated by various state and program entities. References Baylor, S. C. (2000). Brain Research and Technology Education. Technology Teacher. 59(7), 6. Carter, T. (2008-2009). Millennial expectations, constructivist theory, and changes in a teacher preparation course. SRATE Journal, 17(1), 25-31. Carter, T. (2008). Millennial expectations and constructivist methodologies: Their corresponding characteristics and alignment. Action in Teacher Education, 30(3), 3-10. Cole, M. (2008). Cultural and cognitive development in phylogenetic, historical, and ontogenetic perspective. In W. Damon, & R. L. Lerner, (eds.). Child and adolescent development (pp. 594-637). Hobeken, New Jersey: John Wiley. Cooper, R., & Morreale, S. (2003). Creating Competent Communicators: Activities for Teaching Speaking, Listening, and Media Literacy in Grades K-6..0 Covey, S. R. (2004). The 9th habit from effectiveness to greatness. New York: NY: Free Press. Danielson, C. (2007). Enhancing professional practice: A framework for teaching (2nd ed.). Alexandria, VA: Association of Supervision and Curriculum Development. Darling-Hammond, L. (2002). Research and rhetoric on teacher certification: A response to “Teacher Certification Reconsidered.” Education Policy Analysis Archives, 10(36), 1-56. DuFour, R., Eaker, R., DuFour, R. (2008). Revisiting professional learning. communities at work: New insights to improve schools. Bloomington, IN: Solution Tree Press. DuFour, R. Eaker, R., DuFour, R. (2005). On common ground. Bloomington, IN: National Educational Service. Donaldson, G. A. (2006). Cultivating leadership in schools: Connecting people, purpose, and practice (2nd ed.). New York: Teachers College Press. Donaldson, G. A. (2001). Cultivating leadership in schools: Connecting people, purpose, and practice. New York: Teachers College Press. Doherty, J., & Bailey, R. (2003). Supporting physical development: A physical education in the early years. Buckingham, PA: Open University Press. Educational Testing Service. (2002). Pathwise classroom observation system orientation guide (4th ed.). Princeton, NJ: Author. Freiberg, K. (Ed.) Educating children with exceptionalities. Annual edition. Boston: McGrawHill. 2010-2011. Fullan, M. (2004). Leadership and sustainability: System thinkers in action. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. Fullan, M. (2001). Leading in a culture of change. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Gardner, H. (1995). Leading minds: An anatomy of leadership. New York: Basic Books. Gesticki, C. (2011). Developmentally appropriate practice: Curriculum and development in early education (4th ed.). Albany, NY: Delmar. Glickman, C., Gordon, S., & Ross-Gordon, J. (2010). Supervision and instructional leadership: A developmental approach. Boston, MA: Pearson, Allyn Bacon. Gordon, A. M., & Browne, K. W. (2011). Beginning and beyond: Foundations in early childhood education (8th ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth. Hallaban, D., & Kauffman, J. (2004). Exceptional learners. Boston: Pearson-Allyn & Bacon. Henniger, M. L. (2004). The teaching experience: An introduction to reflective practice. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Person Prentice Hall. Hord, H., Roussin, J.L. & Sommers, W.A. (2010) Guiding Professional learning communities: Inspiration, challenge, surprise, and meaning. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin. International Society for Technology in Education (2002). National educational technology standards: Preparing teachers to use technology. Eugene, OR: Author. Interstate New Teacher Assessment and Support Consortium (1992). Model standards for beginning teacher licensing and development. Lucas, S. (2007). The art of public speaking (7th ed.). Boston: McGraw-Hill. Marion, M. (2011). Guidance of young children (8th ed?.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson. Marzano, R.J., & Waters, T. (2009). District leadership that works: Striking the right balance. Bloomington, IL: Solution Tree Press. McGuire, J.B., & Rhodes, G. (2010): Transforming your leadership culture. San Francisco. CA: Jossey-Bass. Mertler, C.A. (2009). Action research: Teachers as researchers in the classroom. (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc. Morrison, G. R., Ross, S. M., & Kemp, J. E. (2001). Designing effective instruction (3rd ed.). New York: Wiley. National Council of Teachers of English. (1996). Standards for the English language arts. Urbana, IL: Author. National Council of Teachers of Mathematics. (1989). Curriculum and evaluation standards for school mathematics. Reston, VA: Author. Papalia, D.E., Olds, S. W., & Feldman, R. D. (2008). The child’s world: Infancy through adolescence (11th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. Parkay, F., Anctil, E., & Hass, G. (2006). Curriculum planning: A contemporary approach (8th ed.). Pearson: New York. Payne, R. K. (2001). A framework for understanding poverty. Highlands, TX: aha!? Process. Picciano, A. (2006). Educational leadership and planning for technology (4th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Merrill Prentice Hall. Pitler, H., Hubbell, E.R., Kuhn, M., & Malenoski, K. (2007). Using technology with classroom instruction that works. Alexandria, VA: ASCD. Putman, R. T., & Borko. H. (2000). What do new views of knowledge and thinking have to say about research on teacher learning? Educational Researcher, 29(2), 4-15. Reeves, D.B. (2008). Reframing teacher leadership to improve your school. Alexandria, VA: ASCD. Richardson, J. (Ed.) (2001). Handbook of research on teaching. Washington, DC: American Educational Research Association. Rose, L. C., & Gallup, A. M. (2003). The 35th annual Phi Delta Kappa/Gallup poll of the public’s attitudes toward public schools. Phi Delta Kappan, 85(1), 41-56. Rushton, S., & Larkin, F. (2001). Shaping the learning environment: conncting developmentally appropriate practices to brain research. Early Childhood Education Journal, 29(1), 25-33. Ryan, K., & Cooper, J.M. (2010). Those who can, teach (12th ed.). Boston: WadsworthCengage. Ryan, K., & Cooper, J. M. (2007). Those who can, teach (11th ed.). Boston: Houghton Mifflin. Senge, P., Cambron-McCabe, N., Lucas, T., Smith, B., Dutton, J., & Kleiner, A. (2000). Schools that learn. New York: Doubleday. Sparks, D. (2002) High-performing cultures increase teacher retention. Retrieved from http://www.nsdc.org/library/publications/results/res12-02spar.cfm. Stanulis, R., & Ames, K. (2009). Learning to mentor: Evidence and observation as tools in teaching. Professional Education, 33(2), 3. Stewart. (2003). Building effective practice: using small discoveries to enhance literary learning. The Reading Teacher, 56(6), 540-547. Stronge, J. H. (2002). Qualities of effective teachers. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development. Vygotsky, L. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes (M. Cole, V. John-Steiner, S. Scribner, & E. Souberman, Eds. & Trans.). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Wilson, S., Floden, R., & Ferrini-Mundy (2001). Teacher preparation research: Current knowledge, gaps, and recommendations. University of Washington: Center for the Study of Teaching and Policy. Wilson, J. (2008). Instructor attitudes toward students. College Teaching, 56 (4), 225-228. Womack, S. (2004). “Modes of instruction.” The Clearing House, 62, 205-210. Woolfork, A. (2008). Educational psychology (10th ed.). New York: Pearson.