History of Japanese Theatre

advertisement

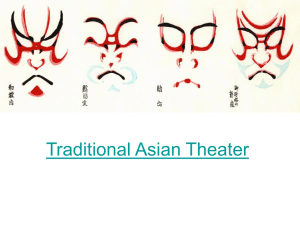

History of Japanese Theatre 1) Japanese Theatre has a long standing history of tradition. 2) This history started with the Noh theatre in 1270 when it was called Suragaku. a. Over time it became known as Suragaku Noh and in 1362 it was shortened down to Noh. b. Between 1333 and 1444, Kiyotsugu Kan’ami and Zeami, a father and son team, wrote the majority of plays still performed today and were truly the great innovators of Noh. c. In 1615, the Noh stage is standardized and Noh begin its long tradition of performance (Brockett, 1987, 293-310.) 3) In 1603, Kabuki Theatre began in bordellos and bars throughout Japan. a. The first performances were done by women and were extremely erotic. b. In 1629, women were forbidden to perform in Kabuki theatres. c. Between 1675 and 1759, Kabuki theatre developed and evolved its characteristics rapidly. The plays usually lasted about twelve hours. d. In 1868, play length was reduced to 8 hours in length (Brockett, 1987, 293-310.) 4) MANY important elements of the dramatic art in Japan are similar to those developed by the Chinese. a. In many cases the story material is obviously the same, and there is great similarity in the methods of producing and acting. b. There were two periods of brilliance in Japan (the fourteenth and eighteenth centuries), and two distinct types of theater: the aristocratic and the popular. i. The former is associated with the famous No plays, which reached their period of perfection during the fourteenth century. 5) The popular theater a. Tradition assigns the beginning of the popular theater in Japan to the early part of the seventeenth century, when the priestess Okuni ran away from her Shinto temple and built a theater in Kioto. b. This theater developed in two ways: i. a "legitimate" playhouse with living actors, ii. and a marionette or puppet show. c. Both these forms of entertainment became popular in the seventeenth century, when the art of the actor and the dramatist improved. d. We may infer that it was then fashionable for members of the aristocracy to attend these plays, also that quarrels in the playhouse were not unknown; for about 1683 an ordinance was passed prohibiting the wearing of swords in the theater. e. The Samurai (knights), being unwilling to lay aside their swords even for a short time, stayed away from the performances; and in consequence the shows promptly deteriorated. f. As among the Chinese, the governing group in Japan looked upon the drama as a means of instructing the lower classes in loyalty and self-sacrifice. i. A very strict set of regulations crystallized about the stage. 1. Every play was produced with elaborate exactness and precision. 2. Much of the beauty of the pieces depended upon the skillful use of parallelism in language, and in the employment of pivot or root words around which the author could display his verbal dexterity. 3. The "invisible" property man was always on the stage, and realistic details abounded. 4. Grief and passion were expressed by violent contortions. T a. The hero would grimace, roll his eyeballs, bare his teeth, and go through every possible variation of distress, while the property man held a lighted candle near his face in order that nothing should be lost to the audience. b. When a man was killed, he turned a somersault before depicting the final agony. c. For many decades the most brutal crimes were performed before the eyes of the spectators,--scenes of torture and crucifixion, harakiri, and bloody scenes of every description. g. After its period of brilliance in the seventeenth century, the popular stage became overloaded with conventions and began to decline. h. Doubtless the absence of the nobility from the theaters contributed greatly to this result. i. Genshiro, a native dramatist and critic of the nineteenth century, wrote that "the theater in Japan had reached the lowest depth of vulgarity, and so continued until the last year of the Tokugawa Shogunate in 1867." 6) The Marionette Theater. a. In the meantime another specialization of the art appeared in the development of the marionette stage. i. The original basis of the marionette or puppet show was the history of the heroine Joruri, whose love stories were related by a chorus while the puppets walked the stage. ii. Gradually dialogue was added; and soon the puppets became so popular that managers brought into their service extraordinary mechanical devices by which eyeballs and eyebrows could be moved, lips would seem to whisper or talk, fingers would grasp a fan, and tiny figures kneel, dance, or swoon with emotion. iii. The stage was furnished with scenery, trap doors, turntables, trapeze appliances, and the like. b. Along with this mechanical development there appeared, also in the seventeenth century, Chikamatsu Monzaemon (or Monzayamon) (born about 1653), one of the most important figures in the whole history of the Japanese drama, and completely identified with the marionette theater. i. His most famous play is said to be The Battles of Kokusenya, the hero of which was a celebrated pirate. 1. The scenes are laid in Nanking and Japan at the time of the last Ming emperor. 2. It contains one of the characteristic situations in oriental drama: namely, the conqueror asking the defeated enemy for the gift of his favorite wife as a tribute of war. 3. In this play are also the treacherous general, the substitution of another child in order to save the heir to the throne, much bloodshed, suicide, and fighting. 4. Spectators have testified to the vividness and force of these representations, to the tenseness of the dramatic situations, and to the impressiveness of the dialogue. 5. Chikamatsu had the gift of diverting the attention from improbabilities and of making his characters bear themselves like tragic heroes. 6. Moreover, he had the great virtue of never being dull. c. The Forty-seven Ronins. i. With the exception of the No plays and the works of Chikamatsu, nearly everything of note in dramatic literature belongs to the eighteenth century. ii. Many pieces from that time had three or four collaborating authors. iii. One of the best known of these collaborators was Idzumo, who had a share in making a play called The Magazine of Faithful Retainers--one of the forty or fifty extant versions of the story of The Loyal Legion, or the Forty-Seven Ronins, based upon a historical incident which occurred in 1703. 1. A member of the samurai (knightly class) was unjustly degraded by his feudal lord for some trifling accident. 2. His companions, all members of his own order, assembled in protest and drew lots for the privilege of killing the unjust master. 3. The lot was drawn and the work done; but the code of their order required that the rebels, one and all, should commit hara-kiri. 4. So the Forty-seven Ronins perished; and every year thousands of admirers make their way to the scene of their burial. a. In the many versions of the story, various additions have been made, such as a love affair, a tea-house scene, bloody and thrilling incidents, and many touches which reveal contemporary manners. b. As a play it is certain to draw a crowded house. d. About the beginning of the eighteenth century the marionette theater began to decline, and writers ceased to produce plays suited for puppets. e. In the late nineteenth century vigorous attempts were made by both noblemen and scholars to improve the stage. i. One of the first features to be condemned was the presentation of scenes of violence and cruelty. ii. Many of the restrictions as to attendance have been removed; women are allowed to appear as actors; and the tendency towards excessive realism has been offset by the practical application of aesthetic principles. The Noh Theatre 7) The staging of a No play. a. A square platform supported on pillars, open to the audience on three sides, and covered with a temple-like roof, forms the stage for a No play. b. It is connected with a green room by a corridor, or gallery, which leads back from the stage at the left, as the audience sees it. c. Here part of the action takes place. Upon the back scene is painted a pine tree, and three small pines are placed along the corridor. d. The orchestra, consisting of a flute, drum, and two instruments resembling the tambourine, is seated in a narrow space back of the stage; while the chorus, whose number is not fixed, is seated on the floor at the right. e. The actors are highly trained, and their speech is accompanied by soft music. i. There are rigid rules for acting, each accent and gesture being governed by an unchanging tradition. ii. The actors are always men, wearing masks when impersonating females or supernatural beings. f. The costumes are exquisite and of medieval fashion. g. The performance is day-long; but as the No play is always short, occupying about an hour, several pieces are rendered during the day. Alternating with them are farces called kiogen, which are short, full of delicate humor, and given in the language of the time without the chorus. 8) The No play. a. The construction of the No play is always the same. i. It begins with the appearance of a traveler, perhaps a priest, who announces his name and purpose of journeying to such-and-such a battle-ground, temple, or other time-honored place. ii. While he is crossing the stage, the chorus recites the beauties of the scenery or describes the emotions of the traveler. iii. At the appointed spot a ghost appears, eagerly seeking an opportunity to tell of the sufferings to which it is condemned. 1. This ghost is the Spirit of the Place. iv. The second part consists of the unfolding of the ancient legend which has sanctified the ground. v. The story is revealed partly by dialogue, partly by the chorus. vi. At its close the priest prays for the repose of the Spirit whose mysterious history has just been disclosed, and the play ends with a song in praise of the ruling sovereign. 9) The content of the No play a. nearly always tragic, is treated with simple dignity. b. There is frequent reference to learned matters, and to the teachings of Buddha. c. The text is partly archaic prose and partly verse. d. Within this slight conventional form are themes relating to filial duty, endurance under trial, uncomplaining loyalty in the face of hardship and neglect, and tender sacrifice. e. The plays are uniformly austere and poetic, remote from the everyday scene, and full of imagination and beauty. i. Kwanami Kiotsugu, who belongs to the second half of the fourteenth century, was called the greatest poet of his time, and the founder of the No play. ii. His son, Seami Motokiyo, was almost equally distinguished. 1. He left instructions as to production and acting, stressing the necessity of avoiding realism on the stage. a. Other relatives and successors of Kiotsugu improved the music, and the Shoguns honored the authors. b. This type of play may well be considered unique in the history of the stage, and an important link between the classic plays of Greece and the poetic drama of modern Europe. Noh Costumes and Masks 1) The Noh players’ costumes, emulating the costumes of an older Japan, suggest that the Japanese were aware that their architecture required the correct costume if a total aesthetic picture were to be made. a. In other words, the adoption of the Western clothing now prevalent in Japan has destroyed a major element in the aesthetic unity conceived by the architects of the past. b. There is certainly a clash of values when the modern visitor, dressed for efficiency, enters buildings built for individuals dressed for beauty (Fairservis, 1971, 139.) 2) Development of Noh Costuming a. Noh staging is very basic in its design. b. While the staging is basic, the clothing is extremely elaborate. i. Noh costuming could be as elaborate as the most sumptuous aristocrats’ robes. ii. In appreciation for performance, audience members would strip off articles of clothing and throw them on the stage for the actors (Lacher, 2002, 9.) iii. Thus, surviving examples of Noh costumes reflect the clothing worn daily by the upper classes of the times and the costumes of brocades and soft, shiny embroidered silks are some of the most sophisticated woven and embellished textiles of Japan (Phoenix Art Museum, 2004.) c. Actors became very much leaders of fashion. d. In Japan’s Noh theatre, the costumes, the fabric, color and design, play a primary role in the characterization of age, gender, social status, and emotional state. e. The beautifully established silk robes and carved wooden masks transform the performer’s body into a mysterious sculptural form (Phoenix Art Museum, 2004.) 3) Noh Masks a. There is a Japanese expression which describes an impassive face as being “like a Noh face.” (Noh text, 2004) i. Noh masks are richly varied and expressive, since the works are the actor are not spoken but conveyed through the mask itself. ii. Thus, the mask is crucial to the role of the actor, and the best masks are said to be able to shout, whimper, scream, purr, or grow silent. iii. The expression of the eyes is considered most important, while sculptural details further define characteristics of the role’s mood and temper (Phoenix Art Museum, 2004.) iv. The mask is hand carved from a single piece of Japanese Cypress, about 12 mm thick and finished with thirteen layers of back. v. The expressions of the masks are both symbolic and ambiguous, and the performers’ art turns the suspended expression into a definite character. (Sichel, 1987, 46.) 1. To express sorrow, an actor flutters a fan before his mask. 2. To show overwhelming happiness he may tilt his mask upward. (Gelber, 1993, 44.) vi. Noh masks are considered to be descendant of the masks worn in gingko theatre. 1. Zeami considered the greatest Noh actor of all time, explained how masks should be made in the book he wrote in 1430 entitled Discourses on the Principles of Suragaku as follows: a. A face mask should not have a long forehead. There are persons today who would begrudge trimming it shorter. It is absurd. If one wears a headpiece- the eboshi, for examplepart of it will be under the mask’s forehead, and the resultant tilt in the mask will bring about a lack of balance that is undesirable. Though it may not be visible if a hairpiece is worn, a high forehead is undesirable because it may show through the scattered strands of hair. The upper part of a long face mask should be cut away. (Araki, 1964, 40.) 4) Noh Accessories a. The main staple of all Noh costuming are the white socks called tabi. b. Tabi is a formal white bifurcated socks. i. Yellow tabi are worn by the comic characters. c. The final ornaments to the costume and the mask are the headband and sash, which create a unified composition that enacts the interpretation of the drama (Phoenix Art Museum, 2004.) KABUKI 1) During the period of the Ashikaga Shogunate (1338-1573), Kyoto was the centre of luxury and effeminate culture among the wealthy, and of increasingly licentious revelry among high and low alike. a. The first half of this era, known as the Muromachi Period (1338-1443), was characterized by: i. an influx of Chinese influence ii. an increase of education among the priesthood iii. gentle arts as Cha-no-yu (tea ceremony), Ko-awase (incense judging), and Ikebana (flower arrangement), among the leisured. 1. Noh, also, during this period, was brought to its perfection and exercised a refining influence over the military class in particular. None of these apparently noble arts, however, was able to check the social evils which grew up, especially during the later years of that Shogunate (1444-1573), in part because of the strict isolation of the sexes demanded by Buddhist ethics and Buddhism's failure to bring matters of sex under the ennobling sanctions of religion. b. Somewhere about the end of the sixteenth century came a dancing-girl, known to us as Okuni of Izumo. i. She seems to have been the daughter of an iron-worker ii. Her presence in Kyoto is traditionally explained by the supposition that she may have been on a tour seeking contributions for a shrine. iii. However that may have been, she met with such welcome in Kyoto that she remained, to be identified with a new dramatic movement rising from the midst of the common people. iv. Okuni's Kagura seems to have been a form of Buddhist nembutsu, a dance of worship in praise of Amida; 1. but her reception on the Kyoto river-beds may well have been due more to her physical beauty and grace of movement than to any appeal in the interests of religion. 2. Here, in any case, about 1596, she was seen by Sanzaburo, who had been sent by his family to be trained for the priesthood in the Kennin Temple, one of the then famous Five Temples, in Kyoto. 3. This youth of a military family had no fondness for the austerities of religion, but led a life of social freedom, and was popularly known for excellence in social arts. 4. He was attracted by Okuni, but found her graceful dancing too restrained to satisfy his taste. Apparently without difficulty, he influenced her to greater abandon, and taught her to dance the popular songs of the day to music of his own composition. 5. This was Kabuki, a slang designation of the time later to be dignified by the use of written characters signifying the art of song and dance. 6. Two trained players thus broke from the bonds of dramatic custom, and, seizing upon material nearest to the popular mind, made another beginning which is now to be traced through developing forms unto the modern legitimate drama of Japan. 2) Kabuki--the Art of Song and Dance--was first called Onna Kabuki, Okuni being a woman (onna) a. although, as her religious chants gave place to popular folk-songs, she wore the garments of men and acted the part of one b. She soon gathered about her a group of players, women, children, and men in the garb of women c. By 1603-1604 Okuni had reached the height of her popularity, and had established stages in various parts of the city. d. Her plays were addressed primarily to the common people; but she soon attracted the attention of the nobility, and was invited to play at the residence of the Shogun. i. There is a record of at least one invitation to play before the Imperial Court in 1603-1604. e. Such success led to imitation, and the number of Kabuki playhouses multiplied; but, in spite of occasional signs of aristocratic favor, Kabuki remained essentially an entertainment of the common people--in reality a protest against social as well as dramatic conventions. f. Those who devoted themselves to its interests were men without honourable employment and women from the prostitute quarters. g. Gross immorality and unbridled licentiousness made it a social danger; and as early as 1608 official order confined it to the outskirts of the cities. h. In 1629 Onna Kabuki was strictly prohibited, avowedly because of its immoral influence, possibly because of its being also a hotbed of dangerous thought and popular freedom. i. The doom of Onna Kabuki seems to have been foreseen by some, for in 1617 Dansuke, who had been conducting a company of women, founded the first company composed of men-players only. i. Men, especially young men, had played in Onna Kabuki; and it probably was not difficult to build up a company from these men ii. As women were forbidden the stage, young men held a monopoly of the female parts; and for this reason the new companies and their plays were known as Wakashu Kabuki. iii. To compensate for the absence of women upon the stage, greater attention was given to matters of costume and scenery; and the plays appear to have retained their full measure of popular favour. iv. The object of official prohibition, in so far as it had to do with public morality, however, was not attained, for grosser forms of prostitution became increasingly prevalent. v. In 1644, when Wakashu Kabuki was most popular, official prohibition was renewed to stop the employment and training of young boys, which, it was charged, was undermining the morals of the warrior class; and in 1652 this second type of Kabuki was banned. vi. Kabuki refused to be destroyed. Older men continued the Kabuki tradition of freedom; and there developed the Yara (adult male) Kabuki, which enriched its presentations with music and the inclusion of better dramatic material to compensate for the relative absence of debasing elements. 1. In the material thus brought into use upon the Kabuki stage four distinct classes may be discerned. a. There are Historical Plays b. Plays of Common Life c. Plays of Unrestrained Action d. Pantomimic Plays 2. In all earlier forms of the Japanese drama the liturgic requirement, on the one hand, or the will of the author, upon the other, governed the stage. Now, for the first time, the actor is seen taking a position of control; and this in a measure accounts for the slight attention given to originality in the material of Kabuki. 3. Not composition but presentation was the problem of the Kabuki stage. With the development of the Yara Kabuki actors began, more generally than before, to train themselves for specific parts. a. In the earlier Kabuki men had often played the part of women; but now, when it had become necessary that they should do so upon all occasions, a professional class of womenfolk (onnagata) grew into prominence. b. Attention to technique and pride in accomplishment secured marked results; and individual actors established family claims to certain rôles. c. Dramatic skill of a high order took the place of personal grace and of sex appeal upon the Kabuki stage. 3) The history of Kabuki is worthy of more careful investigation. a. Kabuki alone, without patronage and amid vulgarity, wrought out a form of drama so generally satisfactory that one can but wonder what might have been its achievement had it received encouragement in freedom and guidance in art. Kabuki Costumes and Makeup 1) Development of Kabuki Costuming a. Kabuki costumes are made to be the focal point for the play. b. Kabuki actors were responsible for providing their own costumes. c. Once they became too elaborate, the actors began to demand the purchase of their costumes from the royalty. (Brandon, Malm, & Shively, 1978, 44.) d. Over history these costumes have not changed. In this day and age, there is a little latitude on colors and patterns, but not on the style of the costumes. (Scott, 1955, 155.) e. The upper and lower parts of the kimono are in two separate pieces concealed by a wide sash for easy costume changes on stage. f. When a performer changes on stage, the costume color may change and design may change, but the pattern on the material does not change. g. The consistency of the pattern is indicitive of Kabuki theatre; as a major portion of Kabuki is constant awareness of the actor. h. This never changing pattern is a constant reminder to the audience that the actor is the same. i. To change the costume strings are pulled from the kimono to reverse the outfit. j. Traditional dressing of major kabuki characters makes them readily identifiable. i. Types of characters: 1. white robed monks 2. “red princess”, 3. a tattooed thief 4. elaborately costumed courtesans walking on high black clogs, 5. a black-hatted court noble are identifiable by the distinctive garb of their class. 6. A housewife would never wear bold patterns as bold patterns usually symbolize a courtesan. 2) Kabuki Makeup a. Kabuki makeup is often considered a mask painted onto the actors face. b. Kabuki makeup is known as kumadori, which involves bold lines in red and blue painted on the face. i. The red lines are associated with virtue or strength, while the blue lines are associated with evil. ii. Ghost and certain animal roles also involve kumadori makeup. (Gunji, 1987, 39.) 1. The kumadori is used to not disguise emotions, but to heighten the expression of the actors. 2. The makeup is applied to follow the natural musculature of the face to show expression with great clarity and force 3. Twenty-seven known types of kumadori exist. a. A courageous warrior is shown with bold black curves for eyebrows, with broad graded lines of red which curve upward from the nose and brow and around the cheek. b. The youthful and handsome hero is identified by two spatula- shaped eyebrows, red lines under the eyes curve up to meet the outer tips of the eyebrows, the top lip is outline in a thin curve in red with a touch of black at each corner. (Scott, 1955, 124) iii. When putting the makeup on, the actor puts on a silk cap that fits tightly around the forehead. 1. This is both the foundation for the wig, as well as a way to hide the hair and smooth down the forehead. 2. The foundation is made of oil and this covers the face, neck and front of the silk cap. 3. Next a white matte makeup is applied to cause a smooth surface. 4. Once the white cream makeup is applied, the actor draws the eyebrows and lips with the color design for his character. (Scott, 1955, 124) 3) Kabuki Wigs a. The wigs of Kabuki have no equal in the world of theatre traditions. b. Most of the wigs are made of black hair; however, they do vary in accordance with age, sex, social class, and status. c. The only wigs that are not black are the white wigs that are used for supernatural beings such as ghost. d. A change in wigs that a particular character may be using is intended to express a heightening of emotions as well as demonstrate psychological change. (Gunji, 1987, 40.) e. The tradition of wearing a wig stemmed from the era of young boys portraying the parts of Kabuki plays.(1612-1648.) i. The young boys would shave a part of their head to show virility. ii. When it became illegal to be a male prostitute in 1648, the actors began to wear kerchiefs over their heads to cover the bald spots. iii. This was later replaced by a dark purple silk patch to look like hair. 1. This was replaced by wigs and the tradition began (Brandon, Malm, & Shively, 1978, 9.) 2. Eighty-four wig types have been clearly identified and labeled. (Brandon, Malm, & Shively, 1978, 109.) a. Each part of the wig has a special name. i. The parts of the wig are the mae gami, the hair above the forehead; ii. the bin, the sweep of hair at either side of the face; iii. the tabo, the coil of hair in the nape of the neck; iv. the mage, the knot of hair on top of the head. 1. When these are combined in different combinations make each individual hairstyle to make each character. (Scott, 1955, 130.) Differences between Noh and Kabuki Costuming 1) Noh characters are usually portrayed in the first half as a false sense of self. When the second half starts, the character usually shows their true self. 2) The change in Noh characters occurs offstage, while in Kabuki theatre, the change occurs on stage. (Brandon, Malm, & Shively, 1978, 109.) 3) These costumes (Noh) also differ from those worn in Kabuki in that they are not identified exclusively with individual roles or plays, but can be under varying circumstances (Phoenix Art Museum, 2004.) 4) The Noh masks and the Kabuki wigs serve the same basic purpose in the two theatres. a. They both establish the age, sex, social class, and status. b. They also help to show mood and emotional change. While a tilting of the head in Noh shows emotions, the position and tilt of the wig in Kabuki show similar emotion changes. 5) The most amazing part of Noh costuming is the elaborate nature of the costumes and the simplicity of the mask. While in Kabuki both the costuming and the makeup are extremely elaborate. a. The simplicity of the Noh mask strongly counters the fancy makeup. While the simplicity of the Noh mask helps to make the emotions more powerful, the fancy makeup makes the emotions in Kabuki more pronounced and obvious. This is a print of the angry, raging spirit of Lady Rokujo from the Noh Play, Aoi-No-Ue, a play about jealousy, rage, hatred resentment and exorcism This is a print of DAIKOKU from the Kyogen Play DAIKOKU. He is one of the seven lucky Gods and is usually seen sitting or standing on two strawwrapped rice bales, always carrying a sack on his shoulder and a hammer of prosperity along with a wonderful sense of humor This is a print of the dragon-god from the Noh Play "ME-KARI". THIS IS A PRINT OF THE NOH MASK PRINCE SEMIMARU SEMIMARU is a Noh play about karma.