AP Poetry Notes 2015

advertisement

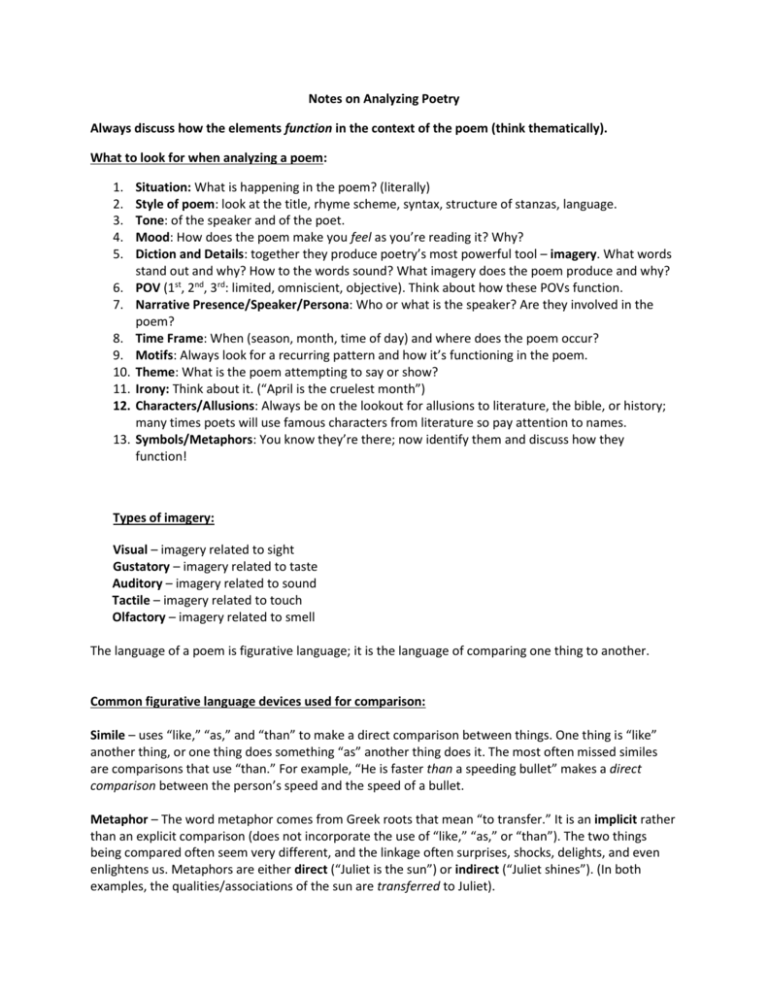

Notes on Analyzing Poetry Always discuss how the elements function in the context of the poem (think thematically). What to look for when analyzing a poem: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 13. Situation: What is happening in the poem? (literally) Style of poem: look at the title, rhyme scheme, syntax, structure of stanzas, language. Tone: of the speaker and of the poet. Mood: How does the poem make you feel as you’re reading it? Why? Diction and Details: together they produce poetry’s most powerful tool – imagery. What words stand out and why? How to the words sound? What imagery does the poem produce and why? POV (1st, 2nd, 3rd: limited, omniscient, objective). Think about how these POVs function. Narrative Presence/Speaker/Persona: Who or what is the speaker? Are they involved in the poem? Time Frame: When (season, month, time of day) and where does the poem occur? Motifs: Always look for a recurring pattern and how it’s functioning in the poem. Theme: What is the poem attempting to say or show? Irony: Think about it. (“April is the cruelest month”) Characters/Allusions: Always be on the lookout for allusions to literature, the bible, or history; many times poets will use famous characters from literature so pay attention to names. Symbols/Metaphors: You know they’re there; now identify them and discuss how they function! Types of imagery: Visual – imagery related to sight Gustatory – imagery related to taste Auditory – imagery related to sound Tactile – imagery related to touch Olfactory – imagery related to smell The language of a poem is figurative language; it is the language of comparing one thing to another. Common figurative language devices used for comparison: Simile – uses “like,” “as,” and “than” to make a direct comparison between things. One thing is “like” another thing, or one thing does something “as” another thing does it. The most often missed similes are comparisons that use “than.” For example, “He is faster than a speeding bullet” makes a direct comparison between the person’s speed and the speed of a bullet. Metaphor – The word metaphor comes from Greek roots that mean “to transfer.” It is an implicit rather than an explicit comparison (does not incorporate the use of “like,” “as,” or “than”). The two things being compared often seem very different, and the linkage often surprises, shocks, delights, and even enlightens us. Metaphors are either direct (“Juliet is the sun”) or indirect (“Juliet shines”). (In both examples, the qualities/associations of the sun are transferred to Juliet). Also, conceits (a type of strange, often shocking metaphor that compares two unlike things to startle readers) and metaphysical conceits are extremely popular in poetry (the term metaphysical seems strange and elitist, but, literally, it just means “beyond the physical.” Often times, metaphysical poets take an abstract concept, i.e. love or death, and compare it with something tangible. Metaphysical poems often take the form of an argument, and many of them emphasize physical and religious love as well as the fleeting nature of life; it appeals to the intellect instead of the emotions). Personification – the giving of human attributes to inanimate objects or to an abstraction. (“The saw snarled and rattled.” In this example, the saw is being compared to an animal, and this comparison helps develop the animalistic imagery). Allusion – a reference to literature, art, or history. Allusions are often employed for thematic purposes. Greek and Roman myths are consistently used in poetry. Sound devices of Poetry: Alliteration – the repetition of the initial sounds of words in a line or lines of verse. (“It bleeds the black blood of the blueberry”). Assonance – the repetition of vowel sounds within words in a line or lines of verse. (“And roll back down the mound beside the hole.”) Consonance – the repetition of consonant sounds within words in a line or lines of verse. (“blueberry”; “The little boy lost his shoe in the field”). Onomatopoeia – the use of a word that, through its sound as well as its sense, represents what it defines. (Bees buzz; “The vorpal blade went snicker-snack”). Rhyme – usually this word refers to “end rhyme” – that is, words at the end of one line having the same vowel sound as words at the end of one or more other lines; rhyming words that do not end with a vowel sound, further, customarily also end in the same consonant or combination of consonants. Masculine rhyme – words which rhyme on a single stressed syllable. (“spears” and “tears” are masculine rhymes, as well as true rhymes. Words that are not true rhyming words but that almost rhyme are called off-rhymes or slant-rhymes. “Dizzy” and “easy” are examples of off-rhyme/slant-rhyme). Feminine rhyme – words which rhyme and have more than one syllable. (“buckle” and “knuckle” are feminine rhymes) Rhyming patterns: Couplet Tercet, or Triplet Quatrain Terza Rima Spenserian Stanza aa bb cc dd, etc. aaa bbb ccc ddd, etc. abab cdcd, etc. aba bcb cdc ded, etc. abab bcbc c (the first eight are iambic pentameter; the final line is an alexandrine). Syntax of Poems Caesura – a structural and logical pause within and only within the line, and usually, but not always, within a metrical foot itself. (“Forlorn! the very word is like a bell.” Immediately after “Forlorn!” there is a pause, a caesura). Stanza – the term used to describe a group of lines in a poem. Enjambment – the intentional interruption of a logical phrase in a line or lines of poetry. The enjambment speeds up the line. Blank verse – lines of unrhymed iambic pentameter. Free verse – verse that is free from metrical design. It might be free from metrical design, but it does have an overall design to it. Repetition – this can refer to the repetition of a single word or phrase or line of poetry. When it becomes a regularly repeated feature of a poem, it turns into refrain, which simply means a line (or even a stanza) which recurs again and again, usually at regular intervals (the chorus of a song is an example). Types of poems Dramatic Monologue – a speaker address a silent listener. As readers, we overhear the speaker in a dramatic monologue. Elegy – a formal sustained poem lamenting the death of a particular person. Epic – an extensive, serious poem that tells a story about a heroic figure (The Odyssey is an example). Haiku – a Japanese form composed of three unrhymed lines of five, seven, and five syllables. Ex: Haikus are easy But sometimes they don’t make sense Refrigerator Idyll – poetry that either depicts a peaceful, idealized country scene or a long poem about heroes of a bygone age. (“Idylls of the King” is about the legend of King Arthur). Lyric – a poem originally meant to sung, but now it refers to any short, concentrated poem expressing personal feelings. Narrative – a poem that tells a story. Ode – usually a long, complex lyric expressing profound emotion. Pastoral – a poem that depicts rural life in a peaceful, romanticized way. Villanelle – a 19-line poem consisting of five tercets (3) and a final quatrain (4) on two rhymes. The first and third lines of the first tercet repeat alternately as a refrain closing the succeeding stanzas and joined as the final couplet of the quatrain.