The policy and practice of the Vietnamese government and trade

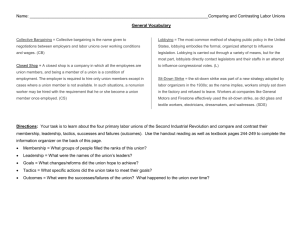

advertisement