Surveillance_All

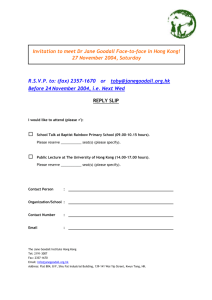

advertisement