- ULCC Publications Archive

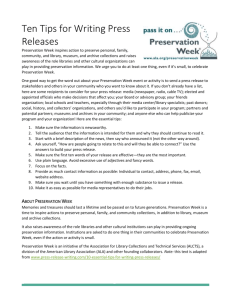

advertisement