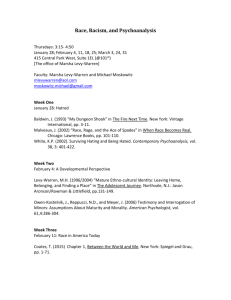

The Struggle to Define and Reinvent Whiteness

advertisement