An Analytic Framework For Dispute Systems Design

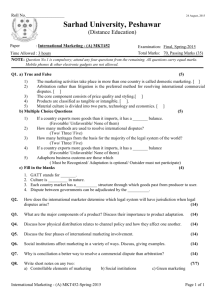

advertisement