rhetorical analysis from textbook global issues local arguments pp

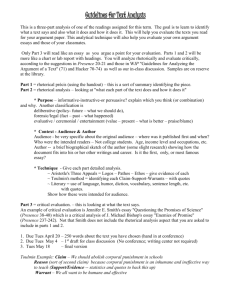

advertisement

1 WRITING A SUMMARY You will find that writing summaries is a key part of writing both rhetorical analysis essays and arguments. In fact, summary writing is one of the most useful writing skills you can learn for academic and professional success. Many other academic and professional genres such as papers to be presented at conferences and proposals for grants or projects also draw on summary writing skills. Using Summaries in Rhetorical Analyses Before you can critique an argument to determine how well it is written and why it is persuasive for certain audiences, you need to have a sound understanding of the argument. This kind of understanding can be fostered through writing a summary of the argument. In writing a summary, you listen carefully to the argument, withholding your own views and judgments, simply trying to grasp what the argument is saying. In a rhetorical analysis essay, you can use your summary to ground readers in the argument, to build a base from which to launch your rhetorical critique. You usually include your summary, which can range from one or two sentences to a full paragraph, early in your essay to give readers a basic understanding of the argument so they will be able to follow and appreciate your analysis. Using Summaries in Arguments The process of summarizing and the summaries you produce also play a major role in writing arguments. Listening carefully and sympathetically to the arguments of others represents a critical step in entering argumentative conversations. Your understanding of multiple perspectives should inform the claims and reasons that you develop in your own arguments. Often, you will summarize views you are applying or enlisting in support of your position. You will also summarize opposing views that you are conceding to or refuting. In addition, incorporating a fair and accurate summary of a text into your own argument helps establish your positive ethos. How to Write a Summary As you are learning to write summaries, you should follow a deliberate and methodical process. Later you may develop your own effective shortcuts. The following chart proposes steps and strategies to write a summary of an argument. STRATEGIES FOR WRITING A SUMMARY Read the article you are summarizing at least two times. Either in your head or on paper (writing your points is usually best), map out the shape or structure of the article by determining how each paragraph and section of the article functions. « How many paragraphs are introductory? « What is the thesis-claim—if it is stated? • Which paragraphs develop the writer's reasons? « Is there an alternative views section? Or are opposing points and objections woven throughout the article? « How many paragraphs make up the conclusion? Go back through the article, paragraph by paragraph or section by section, and translate the writers ideas into your own words. Try to state in one sentence the main point of each section or paragraph. Take stock of the length of the summary you will be writing. Choose the drafting approach that works best for your needs. To produce a summary of 200-350 words, draft your summary by combining your point statements from each paragraph. Once you have strung together these sentences, experiment with ways to combine and condense them into clearer, more concise and coher ent statements. For a one- to two-sentence summary, you can condense your paragraph summary down to the overall thesis-claim of the argument. Alternatively, you can try to identify, extract, and refor mulate that main idea after achieving a good understanding of the article. Begin your summary by identifying the writer, the title of the article, and your own statement of the writers overall thesis-claim. 2 In revising your summary, be sure you have used attributive lags (Finn argues ..., Finn asserts. .. , According to Finn, .. .) every lew sentences to indicate that the ideas you are expressing belong to I In1 writer, not to you. (continued) • In revising your summary, check it for these features: • neutrality (you should keep your own views and judgments out of a summary) « fair and balanced coverage (your summary should be true to the importance of the ideas in the original article) » conciseness (you should use language economically—use the most direct and clear language with no wasted words) coherence with smooth, logical movement from sentence to sentence minimal or no quotations (only quote if you want to give the flavor of the article or if you can't do justice to the writer's ideas otherwise) and citation of page numbers using the documentation system your instructor specifies (Modern Language Association, American Psychological Association, or Chicago Manual of Style) Test of a good summary: Would the writer of the article accept your summary as an accurate and fair abstract of his/her argument? The following example is a summary of the article "The e-Waste Crisis." The annotations help to identify the features of an effective summary. Example of a Summary In the article "The e-Waste Crisis," Basel Action Network claims that the United States and Canada lead the world in the environmental destruction and social injustice caused by the dangerous dumping and exporting of toxic electronic waste. According to BAN, four billion pounds of e-waste, the largest single type of waste, were produced in 2005. Over 85% of it was burnt or deposited in landfill and 12% of what was recycled ended up in developing countries. The toxins in this waste endanger the environment and communities where it is dumped, the workers handling it, and even the rest of the world through polluted air, water, and food. BAN asserts that many complex factors are compounding the e-waste crisis. First, electronic gadgetry is made up of highly toxic substances such as lead, mercury, and arsenic. This gadgetry, which rapidly goes out of date, is labor intensive to take apart to recycle parts, and the market for this equipment is growing, creating more e-waste. Second, lack of regulation also removes any incentive to recycle this waste and falsely labeled recycling hides the disposal methods. The biggest problem, according to BAN, is that the U.S. is the only developed country that did not ratify the 1989 Basel Convention, controlling trade of e-waste and prohibiting the exporting of hazardous waste from rich to developing countries. The Basel Action Network and the Silicon Valley Toxics Coalition have documented on film the exporting of this waste to poorer countries in Southeast Asia and Africa where children and adults are exposed to dangerous toxins as they cheaply and primitively disassemble and burn this waste. BAN calls for legislation and a national system to confront this crisis. Finally, BAN argues that states, cities, U.S. prisons where the waste is often handled, poor countries around the world, and a few responsible companies, responding to the EPA's weak voluntary solutions, should not have to bear the brunt of the e-waste problem. (317 words) Additional transitions and attributive tags keep the focus on the main points. Concluding sentence wraps up the summary. First sentence identifies the article and author and states the main idea. Attributive tag focuses on the author. Attributive tag focuses on the author. Example of a One-Sentence Summary 3 In its web article "The e-Waste Crisis," Basel Action Network claims that the United States, which has refused to adopt global regulations, leads the world in the discarding of toxic electronic waste in municipal dumps and the exporting of this toxic waste to poorer countries, and consequently contributes substantially to environmental destruction and social injustice. DISCUSSING AND WRITING Summarizing an Argument Working individually or in groups, return to Ed Finn's argument "Harnessing Our Power as Consumers" on pages 29-31. Follow the steps and strategies for writing a summary explained in this section. Write a 250-300 word summary. Then write a one-sentence summary that captures the main claim of the article. Finally, write a short reflective paragraph discussing the challenges you faced writing these summaries. What was difficult? How did you solve any problems? WRITING A RHETORICAL ANALYSIS This section discusses the main thinking and writing moves of a rhetorical analysis essay. Particularly, it explains how to find a focus and formulate a thesis statement for your essay. It concludes with an example of a student's rhetorical analysis, an essay by Tyler Bernard analyzing the rhetorical effectiveness of two advocacy films. The Purpose and Audience of a Rhetorical Analysis A rhetorical analysis is basically an interpretive argument. When writing a rhetorical analysis, you can usually assume that your audience is neutral or uninformed yet receptive, rather than hostile and antagonistic. Because a rhetorical analysis essay is an interpretation—your interpretation of someone else's argument—it has a persuasive purpose. Your main strategy is to make your interpretation persuasive by providing textual evidence and good discussions of all your points. Your goal is to make your audience see the argument you are analyzing your way. However, your essay may be as heavily analytical as it is persuasive. Purpose. Your motivation and specific purpose for. writing a rhetorical analysis may be described in three ways: 1. You may be writing as a citizen trying to make sense of the argument to develop your own views on the issue. 2. You may be writing as a student producing an academic essay critiquing an argument to show your understanding of the argument and of rhetorical analysis. 3. You may be writing as a citizen or student who is analyzing an argument in preparation for writing your own argument to join the public conversation on an issue. Audience. The usual audience for a rhetorical analysis is other people who are interested in the issue explored in the argument and who want to know what it contributes to the public conversation on this controversy. Your audience might be other citizens and students who like yourself want to sort out the various public arguments to choose the most reasonable, informed view. Or occasionally, you may have a more specific audience in mind, such as a defined group of stakeholders (students who are considering volunteering time to help refugees; students considering becoming vegetarians; commuters who drive cars to campus, and so forth). . The Structure of a Rhetorical Analysis In envisioning a structure for your rhetorical analysis, think of your essay as having these main parts: • An introduction providing a brief context for the argument and perhaps for your analysis (a statement explaining your interest in the article and ils timeliness and relevance) « A brief summary of the argument lo provide your readers with a foundation and basic understanding of the argument you are analyzing A thesis statement that indicates the focus of your analysis and perhaps maps out the points you will discuss 4 A well-developed main section devoted to your analysis of the article and evaluation of the rhetorical strategies, perhaps considering the articles rhetorical context, purpose, and target audience. A brief conclusion that wraps up your analysis and possibly comments on the significance of the article's argument Analyzing the Argument A rhetorical analysis essay should reflect your close examination of an article. Give yourself time to think deeply about the article whose argument you are analyzing. Here are some strategies that will help you engage thoughtfully with an argument. Note how these strategies incorporate the summary writing strategies from the preceding section of this chapter. STAGE 1: STRATEGIES FOR ANALYZING AN ARGUMENT 1. Reach a thorough understanding of the article you are analyzing. Familiarize yourself with the article and its argument by reading it several times. 2. Follow the strategies for writing a summary on pages 39-40. Map out the shape of the argument, and identify its main points. At the summary-writing stage, remember to put aside your own responses and try to get inside the argument and see the issue from the writer's perspective. Write a summary of the argument, perhaps both a longer summary of 150-250 words and a short onesentence summary. 3. Examine the argument the article is presenting. Using your under standing of the main elements of an argument, ask yourself questions and jot down notes: What is the question-at-issue? What is the writers core argument? What reasons and evidence does the writer present? Because all stakeholders are driven to present their views to change readers' perspectives, the question is not, "Is this writer biased or passionate?"(Of course, arguers are passionate!) Ask instead, "Is this writer arguing rationally with evidence to support reasons or only ranting and name calling, skewing evidence?" Is the writer aware of alternative views and fairly representing and refuting them? Is the writer addressing objections, or merely changing the topic and skating over the surface? • How responsibly does the writer develop the logos of the argument and use appeals to pathos7. Your notes in response to questions like these can be either very thorough or rough, depending on how you work best and what your instructor requires, 4. Respond personally to the argument. Looking back through the argument and through your notes, identify spots or features of the argument that particularly catch your attention. » What passages or features stand out by impressing you, disturbing you, or puzzling you? • Where does your interest shift to a higher gear, or where do you disengage in frustration or disagreement? • What will you remember about this argument? What leaves you thinking? To generate ideas for your rhetorical analysis, you may find that freewriting in response to these questions helps you connect with the argument in an interesting, provocative way. Now that you understand what argument the writer is making and have explored your response, you can dig deeper into its rhetorical construction. Choosing a Focus for Your Rhetorical Analysis and Writing a Thesis Statement You may find that you want to work with Stage 2 strategies at the same time as you grapple with the argument itself. With either process you choose, the goal is to reach a thorough understanding of this article and to discover some independent perceptions that you can share with your own readers. As you apply the rhetorical concepts and the questions presented in the charts in the section "A Brief Introduction to Rhetorical Analysis" (pages 31-38), try to refine your thinking about the argument you are analyzing and zero in on a focus. A typical focus for a rhetorical analysis essay is either (a) why and how an argument works for its target audience or (b) why and how the argument works for you or others who are not part of its target audience. Basically, how does this argument contribute to the public conversation on (his issue? 5 STAGE 2: STRATEGIES FOR FOCUSING YOUR RHETORICAL ANALYSIS AND WRITING A THESIS STATEMENT 1. Think about the rhetorical context of the argument. Building on your working understanding of the argument, think specifically about the writer, the writers angle of vision, the motivating occasion and writers purpose, the kairos of the argument, and the target audience. Analyze how rhetorically effective and persuasive the argument is. Most writing on global issues in the public sphere has a civic component, appealing to readers as citizens, voters, or consumers. Speculate about how the argument is working persuasively on them and how it might work for other readers. Who are the stakeholders in this argument? What values and assumptions would readers have to hold to be persuaded by this argument? Think about how this argument fits in the larger public conversation on the issue. How is the writer framing the issue or articulating the problem? How does this argument intersect with other arguments you have read on the same issue? 2. Think about your relationship to the target audience and the argument's effectiveness for you. If you are not part of the target audience (for instance, not a supporter of the advocacy group, not a regular reader of the news commentary journal where the argument appears, or not a proponent of the view espoused by the article), ask yourself questions like these: What features of the argument are persuasive to you? What features of this argument make it a reliable, responsible view on this issue? Where do the reasons, evidence, or argumentative strategies (for example, handling of alternative views) seem effective to you? What questions or points would need more confirmation? 3. Choose several important features of the article that you want to discuss in depth in your essay. Identify points that grow out of your rhetorical thinking about the argument. These points should go beyond the obvious and should bring something fresh and insightful to your readers that will help them see this argument with new understanding. You may want to list your ideas and then look for ways to group them together around main points. 4. Write a thesis statement for your analysis. Given that you cannot discuss every rhetorical feature of the argument, from your notes and any freewriting you have done, identify the focus for your analysis. For your audience, which features of this article's argument merit interpretation and discussion? Which points do you think shed important light on the rhetorical effectiveness of the argument you are analyzing? In your thesis statement, you may choose to map out two or more points that you will explore in your essay. You may need two sentences to present these points. Here are some examples of thesis statements for a rhetorical analysis essay. Three Sample Thesis Statements 1. Ed Finn's editorial "Harnessing Our Power as Consumers" works beautifully to persuade an audience sympathetic to social justice issues by using Finn's personal experience to build a positive ethos and by making points about historical labor struggles, boycotts, and the causal link between cheap products and overseas labor. 2. Ed Finn's editorial "Harnessing our Power as Consumers" will not reach dissenting readers because he fails to acknowledge opposing views of sweatshops, relies heavily on his own experiences as a consumer, and does not address readers' real financial need for cheap products. 3. Although PETA's (People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals) YouTube video Meet Your Meat makes powerful verbal and visual appeals to pathos, the film fails to persuade meat eaters to change their ways because it distorts its evidence and disregards all other perspectives. Drafting a Rhetorical Analysis 6 Once you have drafted a strong working thesis statement, you are ready to write a complete draft of your rhetorical analysis essay following the suggested structure on pages 42-43. The main writing moves that will make your rhetorical analysis essay persuasive as well as engaging are (1) setting up your points clearly and delivering on your readers' expectations by following through with lively explanations of them; and (2) using specific textual evidence, both examples and quotations, to give validity and credibility to your points. An Example of a Rhetorical Analysis Essay The following rhetorical analysis essay by student writer Tyler Bernard presents a comparative analysis of the two advocacy films Meet Your Meat and VEGAN. For the People. For the Planet. For the Animals. Tyler's rhetorical analysis grew out of his class's study of global food systems and factory farming, a system in which large businesses raise masses of animals in confinement, feeding them to promote rapid growth for slaughter. You can find these films at YouTube.com. Notice how the title sets up the focus of the rhetorical analysis. Other features and strategies of Tyler's analysis are identified by annotations. film Bernard | First sentence addresses the kairos or timeliness of the films. Introduction I supplies im-I portant back-I ground in-I formation on the creators of the films. Three-sentence thesis statement sets up rhetorical analysis, contrasting the rhetorical effectiveness of each STUDENT VOICE: Responsibly Motivating the World? —A Rhetorical Analysis of Two Advocacy Films by Tyler What does it mean to live responsibly in a globally connected world in which a growing population is making heavier demands on resources? According to the groups Nonviolence United and PETA (People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals), being a responsible person is closely correlated with what we choose to eat. These advocacy organizations emphasize different global problems such as global starvation, inefficient resource management, and global warming, yet come to the same conclusion: Avoid any and all food products related to animals. On its Web site, Nonviolence United's mission is building a better world "reflective of our shared values of justice, kindness and compassion for other people, for the planet and for animals" and it focuses on "need, not greed," as its film states. PETA, on the other hand, takes a much stronger stance in defense of animal rights by focusing on the four sites of long-term animal suffering: "on factory farms, in laboratories, in the clothing trade, and in the entertainment industry." Both advocacy organizations have created videos distributed through YouTube to communicate their goal to a general audience, but especially to meat eaters: to convince people to remove all forms of meat and animal products from their diets. However, whereas Meet Your Meat, PETA's film, falls short of successfully communicating the importance of living a vegan lifestyle, Nonviolence United's VEGAN. For the People. For the Planet. For the Animals, succeeds. Meet Your Meat lacks logical argument and factual evidence, over-emphasizes the emotional element, and creates a despairing tone. In contrast, the Nonviolence United film clearly outlines a logical argument, plays moderately on emotions, and takes a hopeful, optimistic tone towards its viewers and the future. Both films are approximately twelve minutes long, use a series of separate images, and rely on narration. Meet Your Meat is composed of many horrifying video clips such as animals being beaten with clubs, living in extreme conditions (such as cramped cages) with other animals, and having their throats slit while fully conscious. These clips are intended to deeply disturb viewers. Titles are given to each horrific clip as it is shown, "Egg-Laying Hens," "Cattle," "Dairy Cows" and "Veal Calves," "Pigs," providing a logical structure to the footage of brutal killing that the narrator describes. In contrast, VEGAN. For the People. For the Planet. For the Animals, is a slideshow of images divided into three sections (the good of people, the good of the environment, and the good of animals). The cordial narrator's voice presents the message of "making choices connected with our values" over softly playing upbeat music. Beautiful scenes of forests and fields alternate with images of starving children, acres of forest cleared for cultivation of animal feed, and dolphins and sea turtles caught in fishing nets. Statistics are then given to support the extent of destruction and to inform viewers how their responsible actions can save the land, water, and other resources. 7 Throughout PETA film's Meet Your Meat, the overall structure and organization of the film attempts to convey its logical, comprehensive content and evidence; however, this reasonableness is deceptive. The structure provides a logical basis for the flow of information, first part one, then part two, then part three, giving the film an appearance of being thorough, as though nothing had been left out, but this "whole story" is not the case. The film's evidence for why people should become vegan is the treatment of animals shown in the film. However, the film leaves viewers with many questions: In what country is this happening? How often and on what scale does this abuse take place? How long has this been happening? To my disappointment, none of these questions was answered. The film intends viewers to assume that the cruel butchering seen in the video takes place regularly in the United States as the normal treatment of livestock. The film also wants viewers to assume that all livestock live a life of suffering and that this suffering will continue indefinitely until enough people have become vegan. Yet because these questions are never answered definitely, viewers can interpret the film in different ways. While some viewers may readily go along with PETA's intended assumptions, others like me may be highly skeptical about the content of this film. In contrast, Nonviolence United does a much more genuinely thorough job of arguing the benefits of going vegan. The film logically progresses through arguments that eating meat contributes to the world's shortage of food, harms humans' health, damages forests, land, and water, contributes to global warming, and causes animal suffering. It supports statements such as "the fewer animal products we consume, the more people we can feed" with statistics. Although the film doesn't cite exact studies, it does mention studies and logically explains the relationship between eating animal products and heart disease, cancer, and the waste of water. At least, the legitimacy of these statements can be tested by viewers through independent research, enabling them to confirm these assertions on their own. The film also claims that the amount of water wasted throughout the production of a pound of meat totals 2,500 gallons, and the amount wasted in producing a gallon of milk is 750 gallons. According to Nonviolence United, one person eating meat and dairy will waste more water in twelve months than a person who let a shower run for an entire year. In addition, it asserts that a vegan will save an acre of trees per year, which is equivalent to recycling over one million pieces of paper per year. The math may be rough, but again, the entire film gives viewers something solid to be able to agree or disagree with. Both films play on the emotions of viewers; however, PETA's film forces compassionate viewers to feel extremely guilty about consuming meat, and the key word here is "forces." Sensitive viewers may feel that they are responsible for the way the animals in Meet Your Meat are treated, and therefore believe that becoming vegan will help put an end to this mistreatment of livestock, but going vegan is not the only solution. Although PETA suggests that putting an end to meat consumption is essential for the betterment of the treatment of animals, it never addresses free range cows and chickens and the manner in which they are treated. It is quite possible for a compassionate person to continue eating meat while not supporting factory farms that mistreat their livestock. In contrast, Nonviolence United's film does not claim that the primary issue with meat and dairy consumption is the treatment of animals, but broadens its appeal and asserts that only two billion people can be fed on a meat and dairy diet whereas the entire world can be fed if people choose to eat vegan. This appeal plays on the emotions of the viewers just as strongly as the images shown in Meet Your Meat. In VEGAN, images are shown of people starving in third world countries, and yet this point is supported with statistics, giving viewers' emotional responses validity. Nonviolence United's film includes other harsh images—of cleared forests and a dolphin and turtle caught in fishing nets— that evoke strong feelings and concern, but these images have a different rhetorical effect on viewers than those in Meet Your Meat. The different manner in which each film presents its emotional and logical arguments also contributes to the contrasting tones and moods of these films. The tone and mood of PETA's film are sorrowful and despairing. They are conveyed by the voice of the narrator, the lack of music, the use of harsh, unedited sounds and noisy factories, and the images of suffering—all of which express the message that these poor creatures are living and dying in such con-ditons because we continue to eat meat. Intended to work on viewers' guilt, this message is somber and discouraging. Ironically, PETA's film undermines itself and fails to succeed for me—and, I imagine, most people—because it doesn't even seem to be hopeful of achieving its goal of ending the mistreatment of animals. The whole film is doom and horror. 8 Essential to understanding the difference between these two films is the impression that each ultimately communicates: PETA's dominant negativity makes its goal s eem unattainable whereas Nonviolence United's film communicates the opposite impression. The hopeful tone of Nonviolence United's film, calling people to responsible, ethical choices, suggests its faith in its ability to move people toward its goal to end world hunger, diminish water consumption, and help create a healthier population. The film maintains this tone of hope through its upbeat music and mixture of both happy and sad images. The calm, pleasant-voiced narrator says that we can put an end to all these problems starting with our forks. This message is well supported and effectively communicated to viewers, making this film a well-constructed argument in support of not just eating vegan, but living a vegan lifestyle. Judging by the reactions of my classmates watching the film, I believe I am not alone in thinking that Nonviolence United's film is a more effective rhetorical piece for a general audience than PETA's film. Works Cited Nonviolence United. Nonviolence, n.d. Web. 1 Feb. 2009. Nonviolence United. VEGAN. For the People. For the Planet. For the Animals. Nonviolence, n.d. YouTube. YouTube, 8 Aug. 2008. Web. 10 Feb. 2009. People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals. "About PETA." PETA. People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals, n.d. Web. 1 Feb. 2009. People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals. Meet Your Meat. People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals, n.d. YouTube. YouTube, 23 Feb. 2007. Web. 10 Feb. 2009. Writer decides to blend his final point into his concluding statement about the films' rhetorical effectiveness. Writer includes a Works Cited list in MLA format to document his sources. Writer explains his third main point, the weakness of Meet Your Meafs tone and how its tone contributes to its failure to achieve its purpose Writer explains the contrasting, more positive appeal that VEGAN makes to viewers by conveying the positive impression that they can help solve the problem FOR DISCUSSING AND WRITING Generating Ideas for a Rhetorical Analysis Essay Choose one of the arguments in this chapter—"The e-Waste Crisis" or "Harnessing Our Power as Consumers: Cost of Boycotting Sweatshop Goods Offset by the Benefits"—or an argument specified by your instructor. Then using the Stage 1 and 2 Strategies charts on pages 43-46, do the following writing tasks in preparation for writing a rhetorical analysis essay: 1. Write your own 150-word summary of the article's argument. 2. Analyze the argument's parts based on the questions under number 3 in the Stage 1 chart on pages 43-44. 3. Freewrite—that is, write in rapid, nonstop, free associational, uncensored mode for a certain period of time, say fifteen or twenty minutes—in response to parts of the argument that impress or disturb you, using the suggestions in question number 4 on page 44. 4. Take notes about the rhetorical features of the argument using the Stage 2 questions on pages 45-46. 5. Then choose several analytical points about the argument and its rhetorical features that have emerged from your note taking and freewriting, and write the thesis statement you would develop in a rhetorical analysis essay if you were to write one on this article's argument.