Law_Review_Article - The Greenbook Initiative

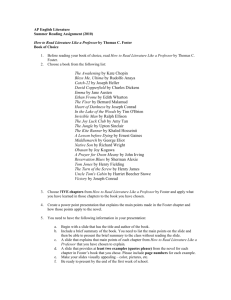

advertisement