Experiential learning as management development

advertisement

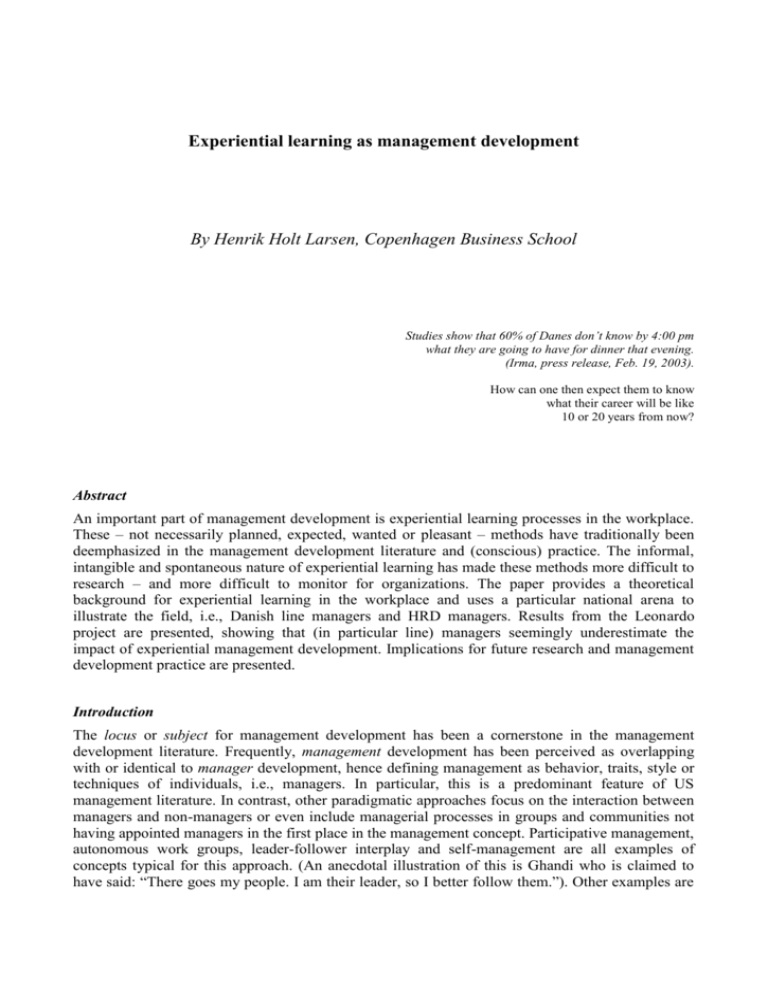

Experiential learning as management development By Henrik Holt Larsen, Copenhagen Business School Studies show that 60% of Danes don’t know by 4:00 pm what they are going to have for dinner that evening. (Irma, press release, Feb. 19, 2003). How can one then expect them to know what their career will be like 10 or 20 years from now? Abstract An important part of management development is experiential learning processes in the workplace. These – not necessarily planned, expected, wanted or pleasant – methods have traditionally been deemphasized in the management development literature and (conscious) practice. The informal, intangible and spontaneous nature of experiential learning has made these methods more difficult to research – and more difficult to monitor for organizations. The paper provides a theoretical background for experiential learning in the workplace and uses a particular national arena to illustrate the field, i.e., Danish line managers and HRD managers. Results from the Leonardo project are presented, showing that (in particular line) managers seemingly underestimate the impact of experiential management development. Implications for future research and management development practice are presented. Introduction The locus or subject for management development has been a cornerstone in the management development literature. Frequently, management development has been perceived as overlapping with or identical to manager development, hence defining management as behavior, traits, style or techniques of individuals, i.e., managers. In particular, this is a predominant feature of US management literature. In contrast, other paradigmatic approaches focus on the interaction between managers and non-managers or even include managerial processes in groups and communities not having appointed managers in the first place in the management concept. Participative management, autonomous work groups, leader-follower interplay and self-management are all examples of concepts typical for this approach. (An anecdotal illustration of this is Ghandi who is claimed to have said: “There goes my people. I am their leader, so I better follow them.”). Other examples are studies of the impact of national culture on managerial behavior, e.g., the Hofstede comparative study of differences in power distance. The less power distance, the less significant the distinction between managerial and non-managerial employees – or managerial behavior and followership - is. To illustrate this two-fold but also blurred conceptualization, let us quote the definition of Storey & Tate who use the term management development “to embrace both manager training and development and higher-order management development activity” (p. 198). But what is “higherorder management development”? This is exactly the problem of the field that there is no commonly explicated and accepted definition of management development. The broadness – and, consequently, intangibleness – of the concept is apparent in the reference mentioned, as Storey & Tate go on stating that “it can be seen that the range of development activity presents a series of options between formal and informal, off-the-job or on/in/through-the-job, employer managed or self-managed, for the present job or future positions, individually contextualized or organizationally contextualized.” The advantage of welcoming in this way a “series of options” is including more features under the management development umbrella. The disadvantage is an up-front contamination of the concept and more trouble when trying to distinguish the concept of management development from career dynamics, organization development (OD), change management or knowledge management. In this paper, we will focus primarily on informal, on-the-job activities, where the locus for learning is the individual (albeit the catalyst for individual management development will in most cases be the organization). Obviously, this discussion of (a particular approach to) management development will make surface an underlying interpretation of the concept of management. The more management is seen as characteristics by or behavior of individuals, the more management development becomes the study of managerial processes rather than features by individuals. Specifically, in this paper we: - challenge the traditional concept of management development as being the development of managerial competencies of individuals - suggest an alternative interpretation of management as being processes of influence between interacting individuals, some of whom may be – but do not necessarily have to be – holders on managerial positions - define management development as any process in an organization which increases the capability (competence) of the organization to deal with managerial processes - present data from a Danish study of management development across industry and size. Hence, the objective of this paper is not to provide a comprehensive analysis of the management concept – and from there go to management development. In reverse, the paper offers a discussion of one particular form of management development, i.e., experiential learning of managerial features, and from that shed some light on the distinction between management development and manager development (and by doing so indirectly illustrate the difference between managerial processes and behavior of individuals who have been assigned to managerial positions). Experiential learning Experiential or self-directed learning has a long history, with milestones being the work of Maslow and Rogers (humanistic school), Lewin (experiential learning), Kolb (learning cycle, cf. below), Piaget, Vygotsky etc. (cf. Stansfield (1996)). Significant roles were also played by Argyris (organizational learning), Revans (action learning), Dewey (inquiry and thoughtful action) and Lave and Wenger (communities of practice). These scholars have all provided fairly comprehensive theoretical models of experiential learning. In addition, many scholars support experiential learning for more pragmatic reasons, typically because the “learning environment” (which in this case is identical to the work environment) was already at hand: On-the-job training is often more economical than formal instruction, for it takes advantage of the physical proximity of workers, the use of free time and idle equipment during a production break, the filling in by subordinates during a temporary absence of superiors, and the virtual absence of excess training since training is tailored to the learning capabilities and needs of each trainee. (Rosenbaum, 1984:21). Despite very different theoretical, ideological and practical backgrounds, these scholars all have in common an emphasis on the learning potential of naturally occurring tasks or experiences (in work life, or outside). In addition, they incorporate in the analysis to a varying extent the learning potential of formal training activities. This latter category represents situations where “real life” is simulated by means of paper and pencil instruments, unstructured group dynamics, instrumented group dynamics, video feedback, and computer augmented feedback, etc. (Mac Namara & Weekes, 1982). The more “authentic” the learning situation is, the more it should occur without deliberate, external staging. The distinction between experiential learning situations and more formal training activities has to do with the nature of the learning site. It is the difference between an actual learning environment, which is “the field”, or the actual organizational environment, compared with an artificial learning situation created by the means of class settings, video equipment, or computers, etc. However, this distinction, when it comes down to actual learning situations, becomes very blurry. An illustration of this would be fast-track programs, which can be regarded with reasonable justification as experiential learning situations, despite the comprehensive criticism that such programs often do not expose participants to “real life challenges”. The assigned jobs, courses etc. are often artificially created and not necessarily (an integrated) part of mainstream organizational life. Another example relates to some of the major theories on experiential learning. It might be questioned whether action learning theory (being a classic model of experiential learning) should have been classified de facto as “experiential learning”, as Revans’ model in particular rested on deliberately (and “artificially”) created group learning situations, which partially took place “away” from the organization. Young and Dixon (1995) do actually make a distinction between action learning “which posits real-world action as a valuable source of knowledge about self, and conversely, views organizational change as a manifestation of individual growth and development”, and learning from experience “which explicates the relationship between challenging/stressful experiences and learning” (ibid.:2). Action learning is often built into formal training programs, but “real-world action” is stressed (McGill and Beaty, 1995), whereas experiential learning in principle is latently present in any task performed by an individual. Common between the two theoretical approaches, however, is the utilization of the learning potential of (certain types of) human action, that is, performing challenging and difficult tasks. In the following, we will use the term “experiential learning” as a common denominator for any type of learning process based on human action involved in performing tasks (typically, but not exclusively) in a work organization, rather than by being enrolled in formal training programs. It is not significant for the analysis of the learning process as such to determine just where the precise dividing line is between formal training and experiential learning as a common denominator for action involving the generation of experiences through performing tasks. However, there are two important reasons for being very conscious about the relative contributions and weaknesses of the two theoretical camps. First, management development represents a continuous, overlapping flow of learning situations which are difficult to separate, and some of which are of an experiential nature, while others are formal training. Second, awareness of the interface between the two “schools” helps us to analyze a crucial issue in learning, which is the role of reflection. As this is an important aspect of - or in fact, a prerequisite for - learning, we will devote the next subsection to this topic. On the whole, there has been a lack of conceptual rigor in the study of and emphasis on the reflection aspect of the experiential learning process. Not only that, but it has also been fairly overlooked that there ever was a problem in the first place. However, reflection is incorporated into many experiential learning theories. A well-known example is Kolb’s learning cycle (1984), which conceptualizes reflexive observation as a phase in the learning cycle. However, the role of reflection has not been well understood (or even emphasized to any significant extent) in existing theories, and the notorious problems related to reflection in this particular type of learning situation has only been given marginal attention. Very appropriately, Seibert (1996:247-248) asks the important question: “It is axiomatic that we learn from experience … or is it?”, and goes on answering the question in the following way: Contrary to popular belief, we do not learn directly from experience. Experience merely provides raw data. This data is rich with potential for learning, but it is not the learning. It is only after we attribute meaning to an experience - that is, when we interpret the raw data of the experience - that learning can result. Thus we learn from the meaning we give to experience, not from experience itself, and we give meaning to experience by reflecting on it (Kolb, 1984; Mezirow, 1991). In short, reflection is an important part of the learning process, but does not unavoidably occur in relation to experiential learning. The reflection that does occur varies in nature and volume with the character of the learning situation and the consciousness of the learner. If no reflection takes place (during or after), the activities cannot be characterized as learning situations, but should be regarded as mere task performance or work related activities. The fact that reflection does take place will not guarantee correct learning. Reflection is a personal interpretation process, and unconscious motives and attitudes may lead to rationalization, projection and other psychological mechanisms by which a person can distort and misinterpret actual circumstances (context, content and outcome) surrounding the learning process. This argument is central to social construction theory, where sensemaking and construction of meaning are seen as inherent aspects of learning (Weick, 1995). Reflection can be conscious or unconscious, it can occur as an integral, simultaneous part of experience, or it can occur at some other time. It can be deliberate and voluntary, or it can be imposed upon the person involved. It can be individual, or it can be a spin-off of a collective learning process. It can also vary in intensity, content, and consequences. And reflection is a significant component of sensemaking and meaning creation. Management development in practice: A Danish example In this section, results from the Danish part of the European Leonardo research project on management development will be presented. The Danish study comprises telephone interviews with a line manager and the person responsible for Human Resource Management in each of 101 companies. The managers being interviewed were asked which management development methods the companies applied. Table 1 shows the percentage of HR managers and line managers that agree to the specific method being used for management development. It appears from the table that traditional methods are used extensively. Internal training and participation in external courses and conferences are preferred to job rotation, e-learning, and mentoring. Table 1: The use of the various methods of management development External courses and conferences Internal training programs Formal training after start in the company Job rotation Mentoring Training via the Internet Temporary outplacement of employees HR Managers Line Managers 60 44 56 49 45 31 33 22 22 24 9 2 2 5 It is not surprising that HR managers speak of a larger scope of training activities than do line managers. HR managers are often responsible for initiating and coordinating management development in the company. It is their professional and organizational domain that is being influenced, and they react accordingly. In contrast, line managers primarily reflect on their own management development, while HR managers include the whole company – though primarily from the HR perspective. Also, HR managers could be expected to have a more positive impression of the management development methods being used, as they are assessing their own work. Studies in other countries – e.g. Norway – show that line managers’ and HR managers’ ‘perceptions of reality’ often differ profoundly. The two groups seem to adhere to two quite different ‘(un)realities’. As it appears from the table, mentoring is given high priority to line managers. A potential explanation for this is that a number of line managers are seeking informal mentors, which is not always known by the HR manager. According to 60% of the HR managers, the company uses external course, conferences, and seminars as methods for management training. Furthermore, 56% of HR managers state that next to external courses, internal training programs are most frequently used. Line mangers consent to this prioritization, but not to the extent to which the latter is used. 49% of the line managers find that external courses are used to a high extent whereas 44% find that external courses, conferences, and seminars are highly used. It appears that line mangers find internal training to be employed more extensively than external courses. Line managers and HR managers agree to training via the Internet and outplacement of employees being the least used methods. The extent to which job rotation and internal training programs is used depends on the size of the company. It takes time and resources to prepare and implement internal training programs. Therefore it is no surprise that large companies of more than 500 employees use internal training programs more extensively than smaller companies, cf. table 2. Thus 60% of the companies with more than 500 employees use extensively internal training programs while the same only applies to 15% of companies with 20-99 employees. The percentage for companies with 100-249 employees is 16, and 32% of companies with 250-499 employees are also using internal training programs fairly extensively. The number of employees also has an impact on to what extent job rotation is used, but here we find greater differences. None of the companies with 20-99 employees uses job rotation extensively, whereas 32% of companies with more than 500 employees do so. It is interesting that 12% of the companies with 100-249 employees use job rotation while only 4% of companies with 250-400 do so. Table 2: The use of management methods by size of company Company size Internal training programs External courses Internal job rotation Temporary outplacement Mentoring E-learning Formal training 20-99 15 32 9 4 11 100-249 16 21 12 7 7 250-499 32 7 4 7 500+ 68 22 32 4 9 18 It can be almost impossible to use systematic job rotation in smaller companies operating with a few employees performing the same functions, such as sales or economy. On the other hand, the characteristic of small companies is that they do not operate with the same division of labor and specialization, as do large companies. In effect jobs in smaller companies are typically broader than similar jobs in large companies, meaning that the former have ‘build-in job rotation’. Our findings show that it takes more than 10 employees before formalized job rotation becomes widespread in the company. A number of companies have become increasingly focused on flexibility, including employees and managers being able to perform several functions and to move fast between different units. This is an argument for staking heavily on job rotation in the company. It is suggestive that industry plays no role in choice of methods. Across industries the preferred method for fulfilling learning needs is thus to let employees attend courses. The almost automatic juxtaposition of (need for) learning and participation in courses is seen in other sectors as well. A representative study among municipal employees and managers reveals that courses are by no means the preferred way of learning (Larsen, 2002a; 2002b). Opting for courses as a method for management development probably reflects conventional thinking among both HR managers and line managers. More recent methods, such as mentoring and e-learning, are only considered to a modest extent as an alternative or supplement to courses. Much seems to indicate, however, that management development is a field in constant transition, and that it is important to many companies to follow-up on the most recent trends. In addition, the larger demand from managers for development may lead to new methods being considered or tested. Certain of the interesting open-ended responses in the study show that employing new managers or employees in the HR department may result in management development being given higher priority. And job rotation across companies may result in positive training dynamics. New generations of managers seem on and off ready to seek new challenges. Professional and collegial networks may help facilitate that change of job proves advantageous to both employees and companies. The need for testing new methods for management development is great. The methods that have proved effective must be consolidated in the companies and in this context both HR managers and line managers play an active role. For the education sector the challenge consists in make future employees familiar with concepts such as mentoring, coaching, and job rotation as tools for management development. In short, the Danish study shows that: the interviewed managers prefer traditional methods for management development more recent methods, e.g. mentoring and e-learning, are not incorporated to any appreciable extent the proportion of training equals company size there is no correlation between choice of method and industry the great challenge of incorporating mentoring and e-learning, and the responsibility for benefiting from this, rests with both companies and the educational sector. Perspectives In this paper we have analyzed how the organization provides a framework for learning processes. The analysis has shown that: - organizations constitute a fertile ground for experiential learning (as well a number of extramural activities (e.g., networking and relationships) also contribute to the learning of individuals) - job assignments and job moves where people succeed when presented with challenge and uncertainty have a large learning potential - experimentation and risk-taking in particular can provide learning opportunities - learning is elicited by the interplay of action and reflection - reflection can be very difficult to achieve, but helps people to make sense out of their actions, and - people who have been “spared” failure and trauma may face what Argyris (1991:101) calls “the learning dilemma”, which is “they are enthusiastic about continuous improvement - and often the biggest obstacle to its success.” What is actually very stimulating for experiential learning may in the eyes of a “rational” bureaucratic organization be very provocative, and could be interpreted either as unprofessional behavior, a waste of resources, (unjustified) impulsive reaction, play or irresponsible risk-taking. This evokes processes of rationalization, where “variation and trial-and-error learning processes are often masked by retroactive accounts of stable and purposeful behavior”, (Robinson & Miner, 1996:90-91). Such organizational defense mechanisms can filter organizational learning processes. To the extent the organization feels uneasy about unconventional behavior or learning, this may seriously restrict the range of situations to which organizational members are exposed. The hidden agenda, which contains a tacit suppression of uncontrollable and unpredictable situations, may eventually “pull the teeth out” of the learning potential of an organization, because it shortcuts some of the most powerful learning processes, much along the lines of what March (1988) calls “the technology of foolishness”. Examples of this are less “dangerous” job assignments, exposure to “organizational citizens” (as superiors, mentors, etc.) rather than “wild characters”, frequent reporting to upper level key people, and more traditional teaching methods being used in career development courses and seminars, etc. Regardless of whether learning is intentional or unintentional, planned or incidental, wanted or unwanted, initiated within or outside the organization, it is there and cannot in most cases be traced back to its many sources of origin. The fact that organizations increasingly break down boundaries to the outside world, join networks or strategic alliances, and exchange information and resources, represents in a sense an after-the-fact acceptance of “cross-boundary learning theory”, which propounds that learning in its acquisition and application does not respect organizational, geographical or life sphere barriers. This makes it easier to create “an open market” for management development. Despite many studies on management development and learning, we agree with London and Noe (1997:74) that “research regarding the influence of job demands on learning and development is needed. Job demands influence development directly through the opportunities they provide and indirectly through the sense of challenge they create.” They also state (Ibid.:74) that “career motivation may […] influence the relationship between job demands and learning”, as people who are strong in career resilience may benefit in terms of learning from difficult tasks and obstacles, whereas people weak in career resilience may suffer from difficulties and obstacles. In short, there is an important research agenda and need for studies crossing the paradigmatic boundary from (exclusively) looking at individuals and formalized structures to a more informal and process oriented view on management development. References: Argyris, C. 1991. Teaching Smart People How to Learn. Harvard Business Review, 69 (3), 99-109. Kolb, D.A. 1984. Experiential Learning. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall. Larsen, H.H., Svabo, C., Andersen, T., Hjalager, A-M, Leth, C. and Scheuer, S.: Læring på jobbet – et overblik. København: KL and KTO, 2002a Henrik Holt Larsen, Svabo, C., Andersen, T., Hjalager, A-M, Leth, C., Scheuer, S. and S. Thomsen Læring på jobbet – metoder og erfaringer. København: KL and KTO, 2002b London, M., & Noe, R.A. 1997. London’s Career Motivation Theory: An Update on Measurement and Research. Journal of Career Assessment, vol. 5, 1, 61-80. MacNamara, M., & Weekes, W.H. 1982. The Action Learning Model of Experiential Learning for Developing Managers. March, J.G. 1988. Decisions and Organizations. Oxford: Basil Blackwell. McGill, I., & Beaty, L. 1995. Action Learning. 2. Ed. London: Kogan Page. Mezirow, J. 1991. Transformative Dimensions of Adult Learning. San Fransisco: Jossey-Bass. Robinson, D.F., & Miner, A.S. 1996. Careers Change as Organizations Learn. In Arthur, M., & Rousseau, D.M. (Eds.), Boundaryless Careers, 76-94. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Rosenbaum, J.E. 1989. Organization Career Systems and Employee Misperceptions. In Arthur, M.B., Hall, D.T., & Lawrence, B.S. (Eds.), Handbook of Career Theory. New York: Cambridge University Press, 329-353. Seibert, K.W. 1996. Experience Is the Best Teacher, If You Can Learn from It: Real-Time Reflection and Development. In Hall, D.T. and Associates, The Career is Dead - Long Live the Career, 246-264. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Stansfield, L.M. 1996. Is Self-development the Key to the Future? Participant Views of Self-directed and Experiential Learning Methods. Management Learning, 27, 4, 429-445. Storey, J. & Tate, W. Management Development. In Bach, S. & Sisson, K. (Eds.). Personnel Management, 3 rd Ed. Oxford: Blackwell, 2000 Young, D.P., & Dixon, N.M. 1995. Extending Leadership Development Beyond the Classroom: Looking at Process and Outcomes. Greensboro, NC: Center for Creative Leadership. Weick, K.E. 1995. Sensemaking in Organizations. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage.