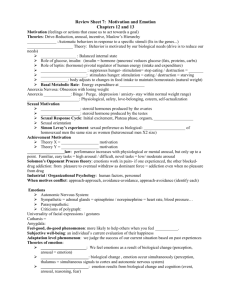

Arousal Theories

Arousal

Sometimes motivation and arousal can get mixed up.

Sage’s definition of motivation stated that motivation was affected by both intrinsic and extrinsic factors that served to energise and direct behaviour.

Arousal is linked to the ‘energised’ state that drives a person to perform, therefore associated to the intensity of motivation.

Definition of Arousal

General mixture of both psychological and physiological levels of activity that a performer experiences; these levels vary on a continuum from deep sleep to intense excitement.

Arousal is not to be seen as good or bad. A performer can be highly aroused as a result of winning or losing a competition or even looking forward to a competition.

Arousal Theories

If the body is put under stress perceived or actual in any way physiologically or mentally then arousal levels in the body are increased.

Typical physiological reactions can be measured by heart rate, BP, EMG, skin responses, adrenaline/noradrenaline measures

1

If an athlete is preparing for a big race they need to be in a highly alert state (arousal). The autonomous nervous system (ANS) help to maintain and prepare the body for action.

The parasympathetic system of the ANS will work to restore the body’s resources for future use.

The reticular activating system (RAS) is responsible for the general level of arousal within the body. Helps with our attention processes.

Arousal can be felt during high intensity exercise i.e. football match, with high levels of adrenaline, increase HR, breathing rate etc.

Aroused states however can be equally associated with fear, anger, tension etc. with similar physiological changes.

Research has shown the levels of arousal can affect levels of perception, attention and movement control, all of which are important in the learning and performance of motor skills.

Appropriate levels of arousal to promote effective concentration, attention and decision making are required.

Coaches need to make sure that performers are ‘psyched’ up (readiness to respond), i.e. intensity of arousal has to be correct. Too high or too low a state of arousal can be detrimental to performance.

2

Drive theory

Early research carried out by Hull(1943) thought that there was a linear relationship between arousal and quality of performance

P = H x D

Performance = habit strength x drive

Hull saw drive as arousal with habit strength seen as the learned response or performance behaviour.

The theory suggests that if the performer is a beginner trying to carry out newly acquired skills then increased drive (arousal) may cause the performer to rely on previously learned skills (which may be incorrect).

Eg. Beginner learns how to serve, does so well however later on under the pressure of a competitive match the beginner reverts backs to underarm serves for safety.

Therefore in the early stages of learning increased arousal can have a negative affect.

In the latter stages of learning (autonomous) increased drive or arousal would have a positive affect. Often called a grooved ‘skill’.

3

However even top class performers have been seen to fail in high arousal situations, this has meant this approach has generally lost credibility.

The inverted ‘U’ hypothesis

Theory originated in 1908 when it was suggested that complex tasks are better carried out with low arousal while simple tasks are performed better with high drive/arousal.

Most coaches can relate to this theory having experienced players under and over aroused. They have also experienced times when arousal levels are spot on with excellent performances resulting.

It has been argued, however that as a general principle, optimum levels of arousal are not the same for all activities or for all performers.

The all-rousing pre-event pep talk, not necessarily the answer to everyone.

**Do activities 5&6 P584**

4

It has been found that motor skills involving simple movements with gross movements i.e. strength, speed which require little decision making need an above average level of arousal.

Activities involving very fine, accurate muscle actions with perception, decision making etc. require a lower arousal.

Important for coach to take this into consideration, even within a team eg. cricket with batsman, bowler & fielder.

Stress management techniques may be required to reduce arousal levels, with past experience, amount of practice and stage of learning also having an effect on arousal levels.

Beginners may need a very low level of arousal as they may find a relatively simple skill quite difficult with a lot of information to take in.

The inability of a performer, usually a beginner to process the relevant information effectively has been linked to what has been called perceptual narrowing and cue utilisation theory .

As arousal levels increase the performer pays more attention to those stimuli, cues and signals that are more likely and relevant in order to help them carry out the task

(cue-utilisation). They focus their attention (perceptual narrowing).

5

Performer’s ability to focus their attention is severely hampered if arousal levels continue to increase. Perceptual narrowing continues with important cues maybe missed.

Extreme levels of arousal can cause a person to go into

‘hyper vigilance’ or ‘blind panic’ where they are not able to make decisions effectively.

Therefore important to keep arousal levels low for inexperienced performers or beginners in a learning situation. Audiences, evaluation and competitive situations are best avoided.

Catastrophe theory

Hardy and Frazey (1987) suggested the catastrophe theory, similar to the inverted ‘U’ theory, with arousal levels increasing causing a positive effect on performance.

However instead of reaching the optimal level and then experiencing a gradual fall off they suggest that it is much more extreme.

Eg. Tennis player in a very competitive game gets argumentative and angry over a call, it is difficult to calm him down, concentration and ability to make correct decisions then drops off.

A lot of ‘mental toughness’ is necessary to recover from the catastrophe and back to optimum arousal.

6

Achievement Motivation

Achievement motivation is related to the questions below

Why is it that some learners/performers achieve and some don’t?

Why is it that certain performers are driven to be more competitive than others?

Murray (1938) identified the human being’s need for achievement as being linked to the personality of the performer.

Competition can be seen as an ‘achievement situation’ however it doesn’t always have to be competitive. People who are prepared to put themselves frequently into

‘achievement situations’ tend to be more competitive.

The level of a person’s need to achieve (drive for success) is seen as a relatively stable disposition. A person with a high need to achieve will have a positive approach, positive success tendency and will strive to achieve a high level of performance.

Atkinson’s personality components of achievement motivation.

He suggested that a performer’s behaviour is greatly affected by their ability to balance 2 underlying motives within ourselves:

7

The need to achieve success (n. Ach) – a person is motivated to achieve success for the feelings of pride and satisfaction they will experience.

The need to avoid failure (n.Af) – a person is motivated to avoid failure in order not to experience the feelings of shame or humiliation that will result if failure occurs.

All sports performers are motivated by a combination of both, the positive feeling of success along with the wish to avoid failure and embarrassment.

The situational component of achievement motivation

He claims a performer will assess the situation they are faced with and evaluate:

The probability of success along with

The incentive value of that success.

High

Incentive

Value of

Success

Low Probability of High

Success

Eg. Playing Tim Henman a game of tennis your probability of success would be very low however, there would be a huge incentive value, with a lot of satisfaction gained if you beat him. The opposite would apply to playing a beginner.

8

Atkinson’s view of what factors contribute to levels of achievement motivation in people can be expressed by the following equation:

Tendency of a person’s = (Ms - Maf) x (Ps x {I-Ps})

Achievement motivation

Or competitiveness.

Ms = motive to succeed Maf = motive to avoid failure

Ps = probability of success

I –Ps = incentive value of success

Current research on achievement motivation

Atkinson’s work formed the base, with a wider perspective being taken, it has focused on the following areas:

The performer’s perceptions of achievement goals

The performer’s perceptions of ‘success’ and ‘failure’ in relation to the goals set

The performer’s perceptions of their own abilities

The performer’s perceptions of the task or situation in relation to their own abilities

The social and environmental factors

Achievement goal theories suggest that a performer’s different ‘achievement goals’ can be either

Outcome orientated or

Task orientated

9

Outcome goal orientation

Someone who is motivated by winning and beating the opposition, who enjoy comparing themselves with others is said to be ‘outcome orientated’.

See success as a result of their ability, ‘ego ‘ important.

Opposite occurs when experience failure, shame, humiliation with deflated ego.

Tend to avoid challenging situations, or select activities or tasks that are either easy or ridiculously difficult.

Task goal orientation

Also want to win but are more motivated by developing their own technical standards or personal performance levels in relation to their previous success, (intrinsic mot.).

Judge success by their own standards so do not fear failure, see it as a challenge to improve.

Performer focusing on effort and personal standards will generally avoid feelings of frustration and be able to stay motivated longer.

In reality most performers are motivated by both outcome and task mastery of goals, however it is important for coaches and teachers to know what is the dominant goals for individuals. Coaches should stress task goals rather than outcome.

10

Stages of achievement motivation

Thought to develop through 3 stages starting in childhood.

Veroff’s 3 sequential stages of achievement motivation.

A child must achieve success in each stage before moving on to the next stage. Many people never reach the final stage in the sequence.

1 Autonomous competence stage – Usually first 3-4 years of a child’s life. Children focus on mastering skills.

Autonomous evaluation builds up perceptions of personal competence.

2 Social comparison stage – At approx. 5years of age children begin to compare themselves with others, focusing on competition. Some focus on winning while others evaluate their own mastery of skills.

3 Integrated stage – there is no particular age level for entering this most desirable stage of achievement motivation. Involves a person in both autonomous competence and social comparison stages. A person who has reached this stage is able to mix and move from one to the other depending on the appropriateness of the situation.

It is important that children are taught when it is appropriate or inappropriate to compete and compare themselves socially.

11

12